Equipped with a marker pen, compass and ruler in hand, Samira Mian is standing at the front of the classroom of a dozen adult pupils of various backgrounds and ages. On the easel behind her is an intricate set of lines, which is starting to take shape as a geometric pattern, as she teaches locals the art of Islamic design in Ealing, west London.

"Our pattern is made up of a 12-sided solid shape with a ring of squares,” the 41-year-old informs the class as she goes around each desk. She is animated as she talks about the beauty and language of patterns with her class.

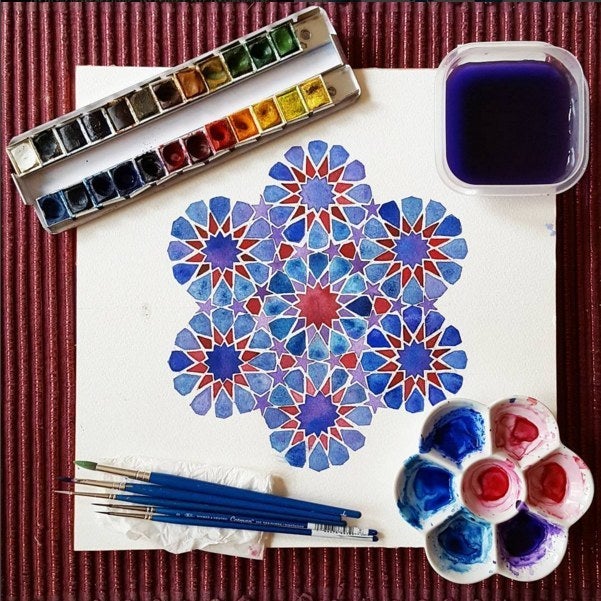

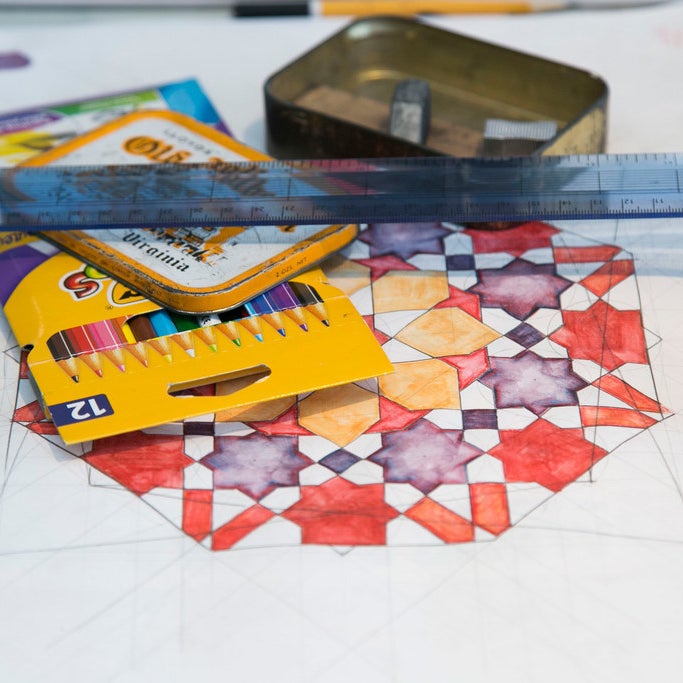

Six-sided stars and octagonal shapes begin to form as pencil markings crisscross crisp white paper. There is order among the seeming chaos of the lines, and the room is quiet and calm as everyone concentrates.

Islamic art is based on sacred geometry, and is not unlike using a spirograph: Think interlocking hexagons and recurring pointy star shapes. Think of the tessellation of azure zellige tiles decorating fountains in Morocco. Think of Alhambra palace in Andalusia, Spain, and the symmetry of its archways laced with calligraphy and stucco chiselled with octagonal designs, or the mesmeric work on the thick pile of a Persian carpet.

It's not hard to see why Mian, a former maths teacher of 12 years, had taken a year out of work to study Arabic in Morocco but instead fell in love with Islamic geometry and hasn't looked back.

She starts a conversation with her students about a TV programme on symmetry by the physicist Brian Cox, and says: "He talks about the way patterns are formed and the underlying rules of nature and physics, that are beneath all the beauty that we observe."

Some in Mian’s class are locals who are completely new to the art form and thought, Why not give it a go?, she says, while others are like Ann, who brought in a photo album from her time travelling in Afghanistan and Iran and has developed a love for Islamic architecture. Then there's a retired maths teacher named Clive, and Tanya, who is a physics teacher. "There's a lot of people who are interested who already have a leg in the world of art and architecture or maths and science," Mian says.

Her classes are popular because of the tangible experience they provide. "We don't do many things with our hands any more – with accuracy and grafting – yet this is something really enjoyable and therapeutic," Mian says. "I love it … Even when I was drawing this yesterday I was like, it matches up so beautifully, there's so much beauty within it."

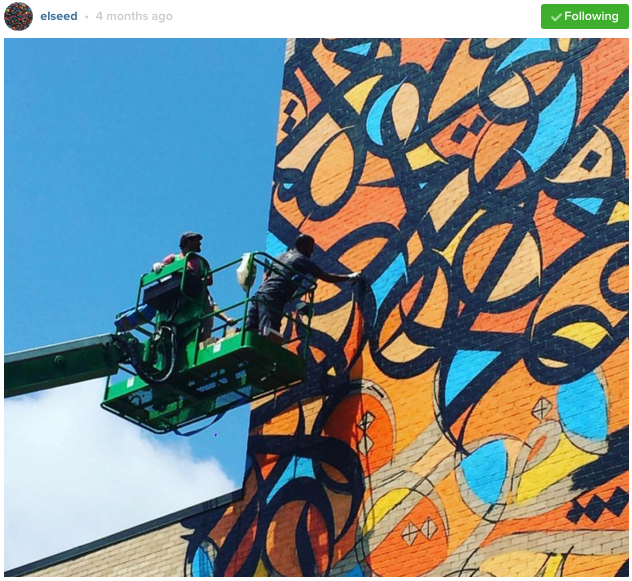

There's been a visible growth in interest in learning the art of Islamic geometry, which Mian describes as a "revival" – from classes in the West dedicated to the art form, to graffiti artists such as the French-Tunisian artist eL Seed, who combines his skills in Arabic calligraphy to create "calligraffiti", to the numerous Instagram posts celebrating zellige mosaics and prints.

"When I first started on Instagram, there were few people to follow. Now there're lots of people. And we kind of know each other online now," says Mian.

"There are workshops [such as the Art of Islamic Pattern] with waiting lists, offered to Granada in Spain, to Fez in Morocco, to Istanbul in Turkey, with dozens of people from all around the world who turn up to learn with these guys [artists Adam Williamson and Richard Henry]," she says. "I mean it's really worth it. And within it there's some sort of searching for the direction of Islam, of the arts and traditions behind it."

Eric Broug, 50, a Dutch artist who has specialised in Islamic geometric art for 25 years and has published books on designs in multiple languages, agreed social media had also helped the explosion of interest in Islamic art. "There seems to be a real trend making things and sharing things online. It is now fashionable," he said in a phone interview. A quick browse on Instagram shows there are over a quarter of a million posts tagged with #IslamicArt.

Broug, who lives in Halifax in Yorkshire, has 14,000 members on his Facebook group, runs workshops, and provides free educational resources online, including YouTube tutorials.

"I was a student in Amsterdam when I came across a book and it spurred me to want to deconstruct and then reconstruct and explain the patterns in a way that was super simple," Broug said.

"People have different motivations … but there's a difference between looking at something and sitting down and mastering something made 600 years ago in Anatolia and 700 years ago in Baghdad."

Back in the classroom, Mian says appreciating beauty in symmetry and patterns is universal, which is why anyone can get into it. Her favourite motif is the central eight-pointed star zellig pattern, often seen on tiles in Morocco.

Traditionally, the art form focuses on the spiritual representation of objects and beings, rather than physical qualities, with some artists believing it helps them gain closeness to God. Such complex patterns and repetition of intricacies is said to remind people of the infinite nature of God.

Such ornamentation was once a part of everyday culture, and began to thrive in the seventh century. The Umayyad caliphate, from 661–750 AD, is often considered to be the formative period in Islamic art, according to the Met Museum in New York, which has 12,000 Islamic art objects spanning from Spain to India. The form picked up regional characteristics as it was adopted by later dynasties including the Safavids in Persia, the Ottomans in Turkey, and the Mughals in the Indian subcontinent.

For Mian, it was important to make a heritage she found so inspirational accessible to the wider public. She found Open Ealing art centre, which has a cafe and is opposite the local mosque, and thought, Hopefully I can be a bridge in the community. Since her 10-week course in the spring, her courses have continued and been rolled out at other art centres, while she has also done demonstrations at festivals.

She hopes to continue to carve out her new career teaching geometric art across the country, and while she won't be going back to maths textbooks for a while, she says: "You can appreciate Islamic geometry on a level of sophisticated mathematics, can appreciate it on an art level, and appreciate it somehow on the philosophical level at how it represents nature." And with that, Mian picks up her compass and goes back to creating her favourite multi-layered zellige design.