As a teenager, Ismail Jeilani had money on his mind. He wanted to be an investment banker, and so he went to Canary Wharf, a folder of CVs wedged under his arm, to look for a work placement to taste the suited-and-booted life in the financial centre while he was still at college.

“I didn’t really know what an investment banker was. It was 'banker equals money',” he laughs.

By the time he'd finished university he'd dropped his dream, and ended up doing something completely different. But money was still very much on his mind.

The reason was that Jeilani, 23, from Haringey, had no idea that fees would have tripled to £9,000 a year by the time he started university in 2012. As a result he'd end up leading a campaign for an interest-free community-based lending system because he didn’t want others to be saddled with interest-laden debt.

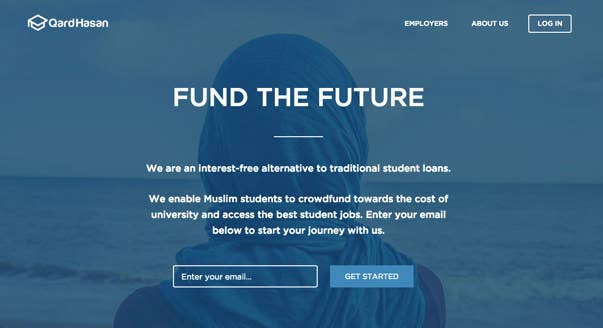

Jeilani believes students who don't want to pay interest, whether for religious reasons or simply to avoid excessive debt, have “lost the right to learn” while waiting for the government to provide an interest-free alternative to the Student Loans Company, which has annual interest rates of up to 3%. So he unveiled QardHasan, a crowdfunding platform and community-based lending system, at a fully booked event of mostly Muslim students from various backgrounds at University College London on Tuesday night.

“I’ve been waiting for this moment for five years,” he said.

Jeilani says it is a project that will provide more options for students – in particular those who can't take out loans with interest for religious reasons – and make higher education more accessible. There are differences of opinion within Islamic thought, however, with some scholars saying it is permissible to take the loan because student fees are written off after 30 years.

“It’s not my story. It’s not your story. It’s our story,” he said, introducing QardHasan.

He said he had been looking for an alternative way to fund tuition fees because he had been in the position himself of facing an ultimatum: “Either I compromise my values, or I compromise my education.”

Like many other 18-year-olds, Jeilani had to become serious about money when he started thinking about university.

“Tuition fees tripled – it forced me in a position I didn’t want to be in, and I started doing things to make my own income, and it thrust me into entrepreneurship,” Jeilani tells BuzzFeed News over a chai latte at a coffee shop on the Strand around the corner from King’s College London, where he studied political economy.

“When I was going to university, I realised it was going to be my debt and I was going to be the one paying for it, with interest – and that added a completely different perspective I didn’t have before.”

He had made up his mind and told his parents he wouldn’t be taking the student loan.

“Keep in mind, being from a minority background, most parents [prioritised] things like education and security in terms of income. Then all of a sudden their child doesn't want to take a loan to study. How are you going to survive the university journey, working at the same time? was the thinking. Because there's no way of pursuing a degree and sacrificing all of that to pay for it.”

Jeilani ended up paying off the full £27,000 worth of fees in his second year of university. He'd made so much money he was able to lend to several other students, which he says secured him a job at Google before graduating.

How did he do it?

It wasn’t easy. He wanted to go to King’s, so he took a year out and got an offer to start his course in 2012. It meant he would start university the year fees tripled.

He says the full £9,000 at King’s was due on 31 January each year. “I had nothing in place in terms of my finances when it came to applying for student loans around April/March before I started university, so I had nine months to figure something out.

“I remember when I spoke to King’s, I said, 'This is my situation, I really want to study and I love the subject, but I’m scared I may not be able to afford the fees.' Their reply was, 'If you can’t afford it you may want to reconsider your options.'"

“It hurt,” Jeilani says. "The whole thing is education is meant to be accessible for everybody, but I felt like I was being blocked off, and it wasn’t my fault."

So he hustled. He worked weekends and evenings, tutoring kids in Arabic, the Qur’an, and economics. “That was good but it wasn’t sufficient. Getting £10, £15, £20, or £25 per hour doesn’t add up to £9,000.” He stayed at home and received some government grants, but it still wasn’t enough.

But things changed after he set up Satifs, a company offering courses to students where he taught through term-time. “First I had one student, then it grew to five, then it grew to classes of 25. The more students, the less they would each pay, and it was great for me as it meant I was able to make enough.

“I know hands down I would have never have done that if I wasn’t forced into a position, so there’s an element of gratitude towards struggle and it teaches you a lot about what you can really do when the pressure is there."

The experience pushed Jeilani to tell other students about his journey. He launched the “How I beat the 9k” series of events, where students who had found entrepreneurial ways to fund their studies toured the country telling other students about it.

He began to press for an interest-free and community-led crowdfunded system, and wrote to the government about the need for an alternative student loans system.

He was told in a letter from what was then the Department for Business, Innovation & Skills in September 2015 that a 10-week government consultation on the issue in 2014 had showed a demand for a "proposed Alternative Finance (Takaful) product” – a type of insurance in Islamic banking in which members contribute money into a pooling system in order to guarantee each other against loss or damage.

The government’s consultation showed 94% of almost 20,000 respondents agreed there would be demand among students and potential students for an alternative finance product that was Sharia-compliant.

QardHasan is Jeilani's response to the problem – his vision for a communal relationship between student, businesses, and communities that supports the education and career aspirations of young people.

Jeilani says student tuition fees are a community-based problem, and his solution has two parts. First, it has a crowdfunding element, with anyone being able to lend money to students, whether it’s £50 or £5,000. Second, his project will fund tuition fees by partnering with firms – this will at first be aimed at students from the Muslim community.

He’s already partnered up with Makers Academy, which runs 12-week coding bootcamps costing up to £8,000 and has agreed to offer interest-free loans, while National Zakat Foundation, a charity that tackles poverty within the UK, has pledged £100,000 in grants for promising students.

QardHasan's pot of funds for student loans and grants for the next academic year is £500,000 already. The technological and financial infrastructure needed is ready as well, as the project is a wing of crowdsourcing platform EdAid and has approval from the Financial Conduct Authority.

The government has now set out its own plans for Sharia-friendly loans, in which instead of paying their loans off with interest, students would make charitable payments to a communal pot that benefits future students wanting to go to university. The plans are included in the higher education and research bill, which has entered the report stage and is being examined in the House of Lords.

A Department for Education spokesperson said: “Studying at university should be open to everyone, no matter what their background. That’s why introducing alternative student finance is one of this government’s priorities. We’re currently taking legislation through parliament that will give the secretary of state the power to offer alternative loan options to students, such as those of the Muslim faith, so that university is truly open to everyone.”

Other measures in the bill are controversial – students and lecturers marched against it last winter – and campaigners say the bill's other reforms will further marketise university education and send fees spiralling.

The National Union of Students doesn't support the bill in its current form – Malia Bouattia, the NUS president, said on Tuesday that the organisation will "celebrate" it being challenged in the House of Lords. “The greatest barrier to thousands of people is the ever-growing cost of tuition fees,” Bouattia said.

When asked why he felt it was his job to come up with an alternative to the current system when the government was already looking at a Sharia-friendly proposal, Jeilani said: “I genuinely don’t have hope in the government building something for a very long time. Let’s say that long time is five to 10 years; how many students would have lost their right to learn because the government didn’t see it as a priority?”

Jeilani says there will be demand for his project: “It's really hard to quantify the damage, and a lot of research will be on the back of case studies and conversations, but there isn't a single Muslim student I've spoken to who would've rejected an interest-free loan.”

He says that in a poll of 2,477 people he carried out while researching his project, 96% of college students said they were more likely to pursue higher education if interest-free loans were available.

“With each story, you hear there's nothing else [apart from the Student Loans Company], and that's why it's become so commonly accepted and taking a loan with interest is what you do.

“For me, irrespective which opinion you take, if you so wish not to take a student loan there is nothing for you. And it’s those people we wanted to work towards helping.”

He says if a student manages to crowdfund a certain amount through his platform, he wants to be able to refer them to a grant partner who may be able to add to the funds.

“The idea is the student is expected to do work working with their community, but we don't want to leave them alone and go through that struggle by themselves – so everything we're doing in terms of partnering with firms, charities, businesses, is geared towards topping up their work.

“We as a company will try our best to support the students." He says when a student crowdfunds his or her first £500 from their community, the company will match that with another £500 in loans.

He admits it’s a small step, adding: “We won't be giving out £9,000 any time soon.”

Isn’t the whole thing too good to be true? “Somebody had to do something," he says. "Fear is never a reason not to do something."