Over a century ago, almost 150 textile workers perished in a sudden factory fire. The incident was inconceivably tragic – and could have been prevented.

In 1901, The Triangle Shirtwaist Company's sweatshop moved into New York City's Asch Building on Greene Street and Washington Place. By 1908, the company would expand to the eighth, ninth and tenth floors.

Shirtwaists in the early 1900s were a staple in women's clothing. They were versatile blouses with varying embellishments that could be tucked into a skirt. Therefore, many companies such as Triangle dedicated their entire staff to producing them.

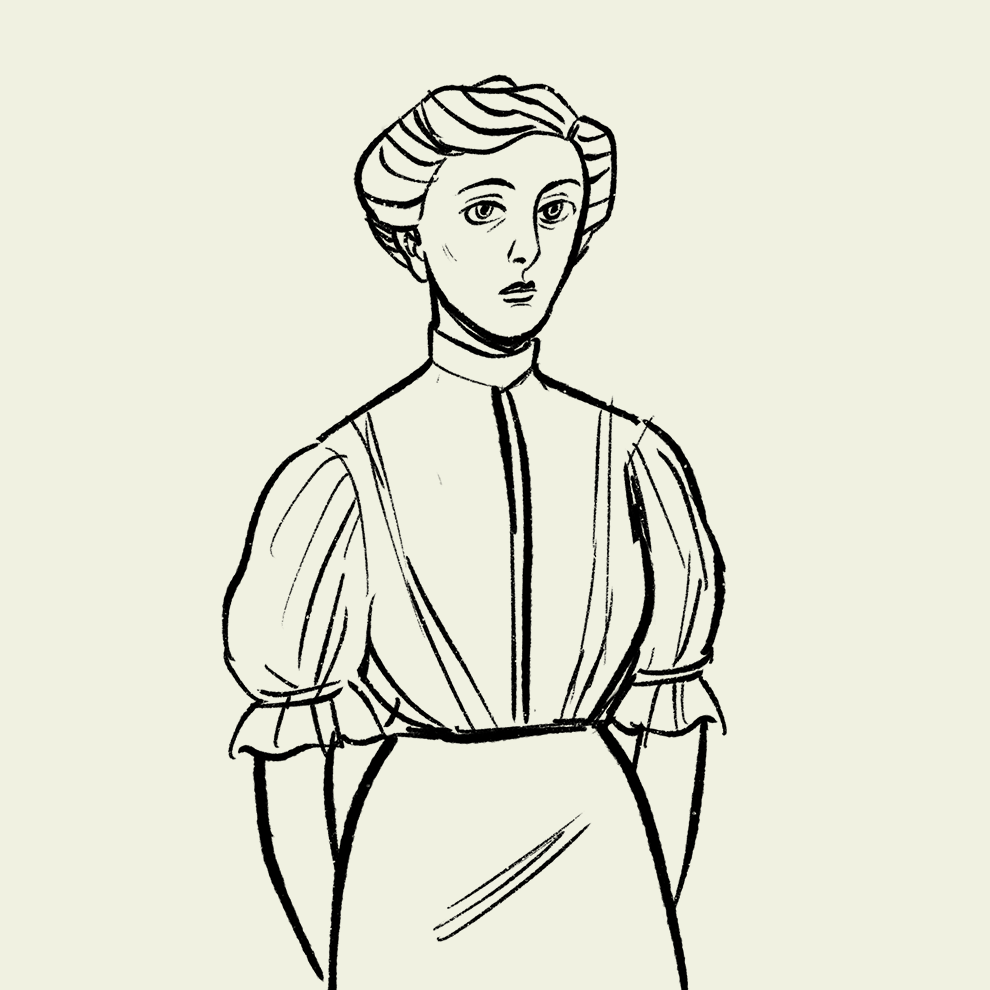

Most of the employees at Triangle were young immigrant women who didn't speak English well or at all. They worked 12-hour-long days with few breaks.

The factory floor was cramped with rows of sewing machines. It probably would have looked similar to this textile factory in Troy, New York, with little room to move and fabric everywhere.

There were four elevators in the building, but only one worked, and it held twelve people at a time.

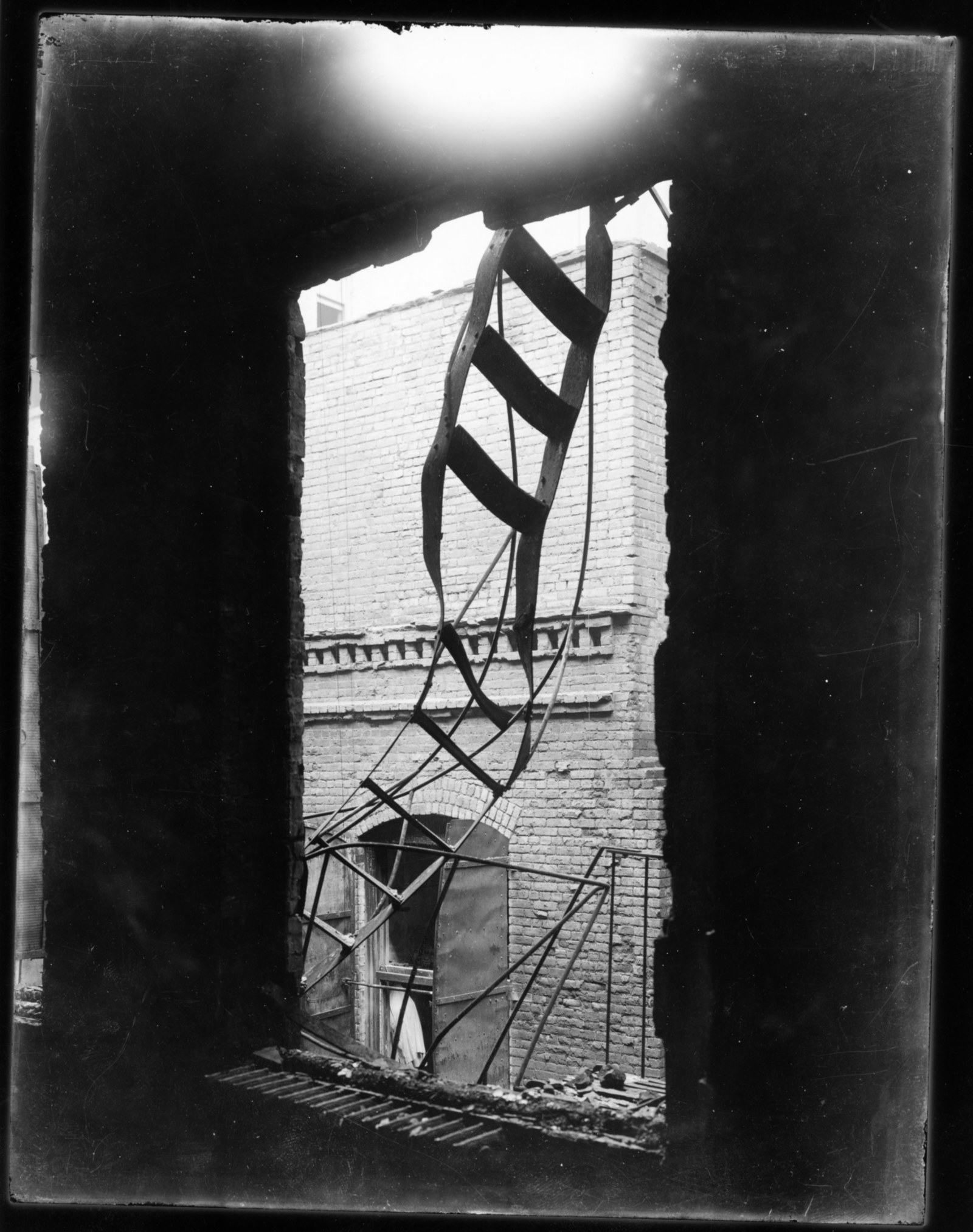

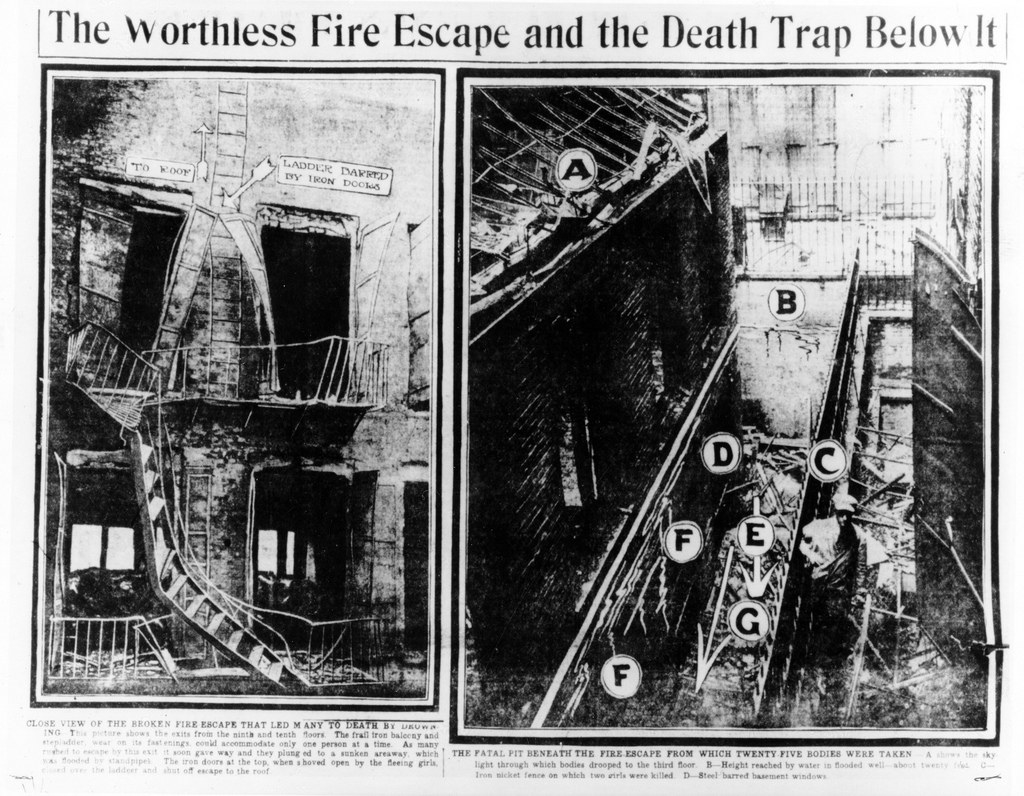

The building was required to have three stairwells but only had two. One exit was always locked from the outside by the owners to prevent theft by the workers. The other exit opened inward. There was a fire escape, but it was narrow, flimsy and impractical for evacuation.

In 1900, the International Ladies' Garment Workers' Union was formed. It united many unions and organized strikes in several cities for better wages, hours and conditions.

In 1909, the ILGWU organized a strike known as the "Uprising of the 20,000," attended by mostly Jewish immigrant women. When an agreement between the ILGWU and factory owners was made, Triangle Shirtwaist didn't sign.

On Saturday, March 25, 1911, a fire broke out in a rag bin on the eighth floor of the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory.

The fire spread rapidly, igniting the fabric all around the room.

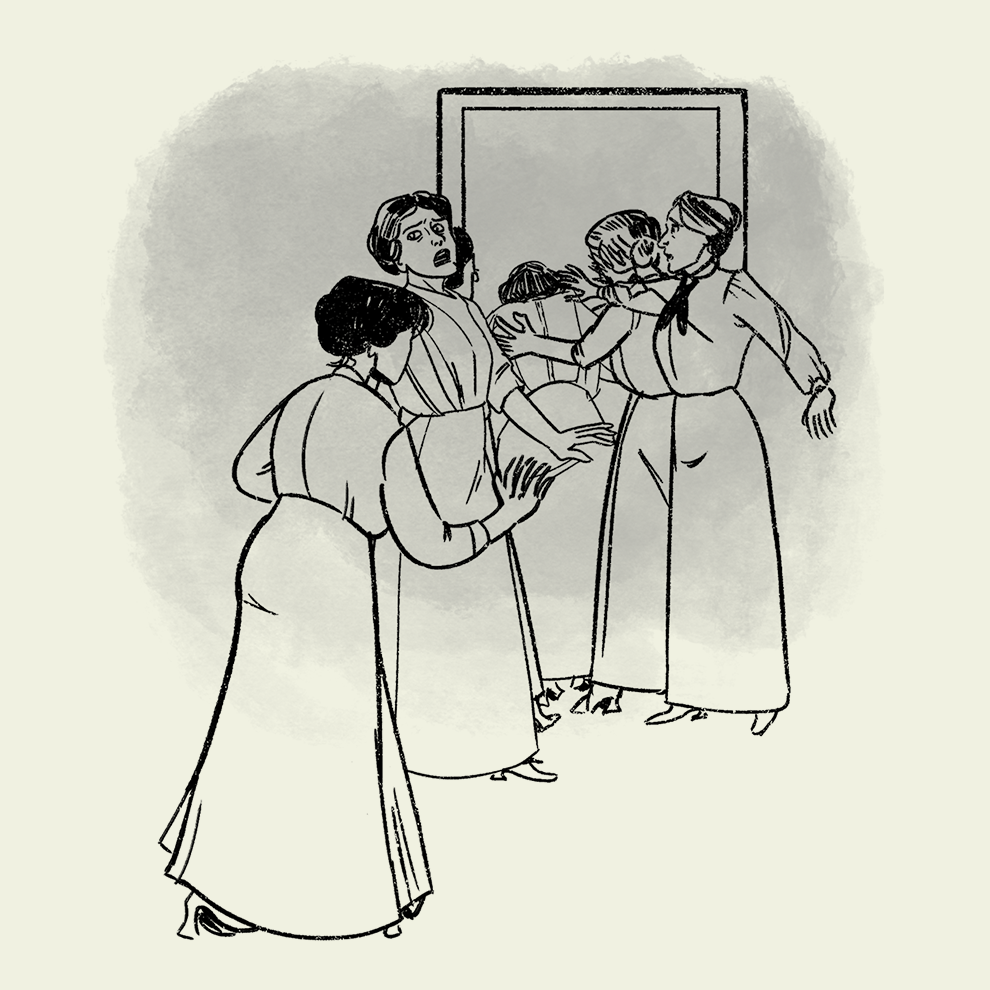

Workers on the eighth floor ran to the doors. One was locked. Finally unlocking it, the door opened inward. So many people were up against the door that it took time to even get out.

Rushing down the stairs from the eighth floor, some people fell, causing a blockage. A policeman helped the fallen so they could continue on.

The executive offices on the tenth floor had been called and notified of the fire. They were able to climb onto the roof and escape to the building next door. The ninth floor, however, hadn't been told of the fire, and only found out when they began to see it.

Ninth floor workers tried two different exits: the Greene Street exit and the Washington Place exit. About 100 workers who chose Greene Street made it out alive. The Washington Place exit was locked.

Some who had tried the locked exit went onto the fire escape, which was already crammed with people. Weakened from the fire, it buckled and separated from the building, flinging the workers to the ground below.

Meanwhile, the elevator operators were making rescue trips to multiple floors. Some ninth floor workers who were locked out of the Washington Place stairwell tried the elevator, but it was already full of eighth and tenth floor workers.

Amidst the confusion, those left behind jumped, or perhaps were pushed, into the elevator shaft.

Others leapt from windows, and some fell on fire hoses, which hindered the firefighting.

Firefighters held out nets for jumpers, but the bodies actually broke through the nets. The fire department's ladders only spanned six to seven floors, so it was impossible to reach the top three floors of the building.

Out of 600 employees in the factory that day, 146 died. The whole incident took place in about 18 minutes.

On April 5th, soon after the fire, the ILGWU held a funeral march on Fifth Avenue. Hundreds of thousands attended and marched.

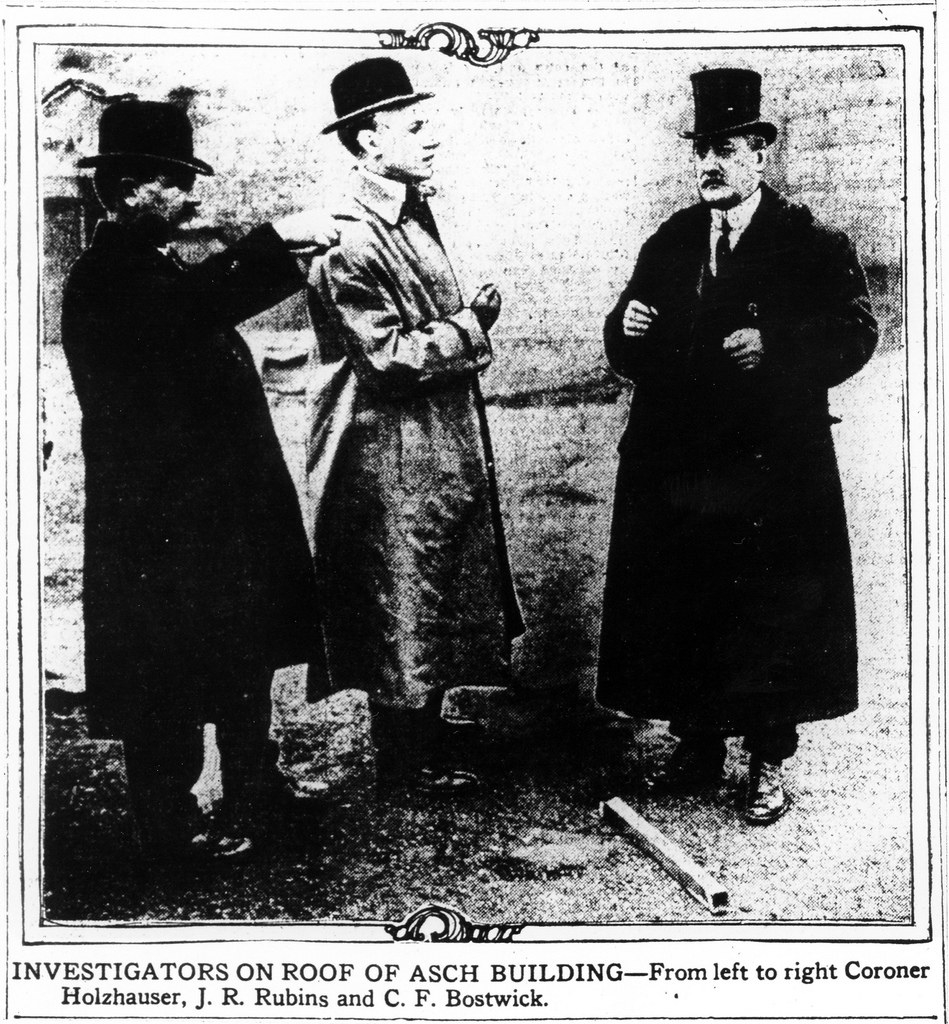

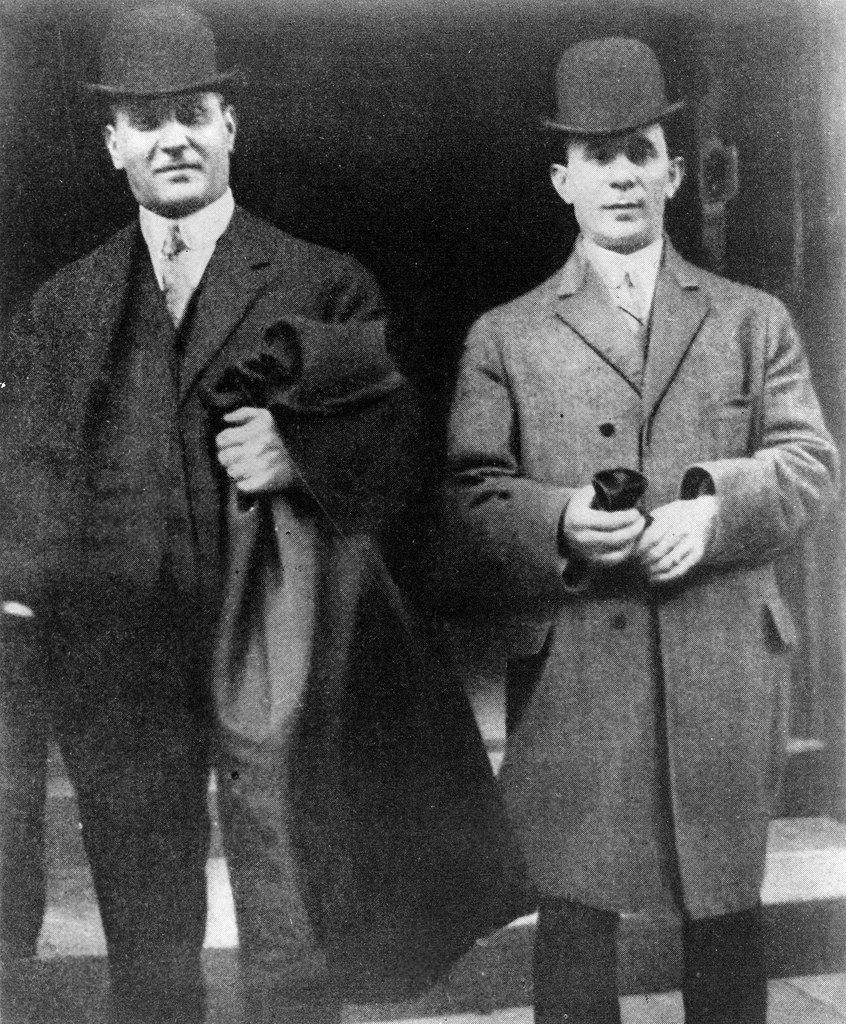

On April 11th, Isaac Harris and Max Blanck, Triangle's owners, were indicted on seven counts of manslaughter. They were acquitted despite having intentionally locked the doors.

It could not be proved that they knew the doors were locked, even with compelling testimony from surviving workers.

Two months later, the Factory Investigating Commission was formed, whose expansive work led the State of New York to pass 36 bills by 1915 that would improve safety for workers. The fire also resulted in the Sullivan-Hoey Fire Prevention Law of October 1911. It mandated that sprinkler systems must be installed in all New York City factories.

In August 1913, Blanck was charged with locking a door in the factory, but was simply fined $20 and even received an apology from the judge for the inconvenience.

The following year, Harris and Blanck settled on 23 civil suits filed against them, paying $75 per death. However, they would continue to insist their factory was perfectly safe.

In 1991, the location of the fire, renamed the Brown Building, was declared a national historic landmark. Today, the Remember the Triangle Fire Coalition spreads information about its history and organizes events on its anniversary.

The victims of the Triangle fire suffered a horrible fate while their employers escaped their due justice. However, in the aftermath of the loss of that day, anger arose, out of which came change for the better. The Triangle Fire is a story of humanity we cannot forget as we continue to push towards better workers' rights today.

Sources: American Experience / PBS, History.com, Paul E. Teague, M.A. and Chief Ronald R. Farr / nfpa.org, Angie Boehm / Global Nonviolent Action Database, Katherine Allen / Readex, Avery Trufelman / 99% Invisible, United States Department of Labor, Howie Levine / Religious Action Center of Reform Judaism, politicalcorrection.org, Harvard University Library Open Collections Program, Cornell University, William Henning, Jr. / NYCOSH