A quick Google search for the term “farming” is likely to produce dozens of articles related to British agriculture, what challenges await the farming industry in the instance of a no-deal Brexit, or a viral TikTok account, depending on how deeply you dive.

What these search results won’t quickly turn up is insight into the practice of private fostering or adoption outside the purview of the local authority, a British phenomenon which gained notoriety in response to a growing population of African student families taking up temporary residence at British universities in the mid-1950s, coinciding with the pending decolonization of West Africa.

In 1955, the childcare journal Nursery World published its first advertisement for a private foster home for a West African child in Britain. By 1974, it was reported that of the estimated 10,000 children privately fostered in England, 6,000 were born to African student parents who personally paid for the arrangement.

Its legacy as a part of black British history has typically been limited to those who experienced it and the few who’d heard about it in passing. But its legacy prevails, and stories are finally being told through projects such as Farming, the directorial debut of British Nigerian actor Adewale Akinnuoye-Agbaje. The film tells the 52-year-old’s personal story of being farmed to white foster parents in 1970s Tilbury, Essex, and forging a place for himself in a racist skinhead gang.

Similarly, Shola Amoo’s Sundance-selected film The Last Tree is a semiautobiographical account of the writer-director’s coming of age after being raised in rural Lincolnshire by a white foster mother.

Here, five people who were raised in white foster homes share their stories with BuzzFeed News about the complexities of integrating into black communities, remembering the African cultures they came from, and, where possible, rebuilding family relationships.

Derek Owusu, 31, Long Melford, Suffolk (fostered from 1988–1995)

When the writer Derek Owusu recalls his foster parents, he conjures up distinctive details, from their parenting style to their heavy smoking habits.

His foster mother was already in her sixties when he lived with her. Owusu described her as “very strict”.

“She had a cane which she used to beat us with when we misbehaved,” he said, “[but generally] it was good. They were lovely.”

Owusu shared the home in Long Melford, Sussex, with up to six other black children. While he knew that the other brown faces were not those of his biological siblings, he considered his foster mother and father to be his parents even though he had regular visits with his biological mum.

“It’s strange because I knew she was my mum, but I also knew my foster mum was my mum. There was no conflict in my mind there at all,” Owusu said.

Speaking about his foster father, the 31-year-old author told BuzzFeed News: “He was quiet. He didn’t get involved too much but was still friendly. I remember him teaching me how to read.”

His foster mother had a firm hand when it came to discipline, but plenty of other special memories defined his complex childhood.

“Christmases were always good. They were always fun. And birthdays. Christmas was very traditional. You would wake up, and there’d be a stocking on your bed. You’d get some presents out [of] the stocking, have a big Christmas dinner, [and] then we’d start pulling the crackers at the dinner table,” he said. “We always had a massive tree and loads of presents underneath it. It was great.”

It’s moments like these when Owusu is able to illustrate the stark differences between the childhood home he lost and the new life he would later be forced to adjust to.

In the summer of 1995, a 7-year-old Owusu made what he thought was a routine trip to London, but his mother had plans to keep him in the capital. “She just told me, ‘Oh yeah, you’re not going back there’, so I didn’t get to say a proper goodbye to anybody, and she took me to Broadwater Farm.”

The contrast between his life in Suffolk and the north London housing estate was stark. The young Owusu struggled to come to terms with his new reality.

“When I came back to London with my real mum, there were no Christmases,” he said. “In Ghana they celebrate Christmas; they have fireworks and that sort of stuff. But in London, my mum was more concerned with working and making money than doing up the house with tinsel and Christmas trees and buying us presents and stuff like that.”

Owusu was bereft. “I think I tried to run away a few times. I wanted to go back badly. I must have cried for about three weeks straight. I didn’t want to do anything,” he said. “I wanted to go back to my family. My mum was just like, ‘Nope!’”

The “massive culture shock” of inner-city London life continued at primary school when all of a sudden a new identity was thrust upon him. “People were telling me that I’m an African, and I’m like, what the heck is an African?” said Owusu.

“I didn’t know what it was until I started seeing the adverts on TV with famine, emaciated children, all that kind of stuff. Obviously I was like, that’s embarrassing. It became an insult in school if someone asked you ‘Are you African?’ You’d get offended,” he said.

In private, Owusu’s inability to reconcile with his mother became more volatile and exacerbated by what he described as his own “behavioural problems”. By his own admission, he “started being a bit naughty” and, as a result, his mother would regularly beat him.

“A lot of the time I thought it was unfair, to the point where she was beating me and I thought, fuck this. So I started fighting back. So we would be fighting and stuff,” Owusu said. “So, yeah, living with my mum, that was a big challenge.”

In the thick of the friction, his mother would deliver the unfortunate news that his foster mother had died from cancer two years after he had left her home.

As he also explained in an essay that appears in Safe, a collection he edited of writing from black men, the news — and its delivery — had a deep-rooted impact on him. He told BuzzFeed News: “I was about 12. I don’t know what it meant for me. All I know is that it hurt me and I was crying a lot. I remember asking my mum why she didn’t tell me, and she was just like, ‘I was trying to protect you.’ And I was like, ‘Okay, if you say so.’”

Now in therapy, which he started attending after what he described as “a breakdown”, Owusu said he is starting to better understand how his unconventional start in life still affects him. His therapist has explained that he has yet to grieve properly for his foster mother and instead is carrying it around with him.

When asked how he felt being privately fostered and then returning to his birth mother, he replied, “It ruined my life”, before quickly backtracking. “I’m exaggerating. It hasn’t ruined my life, but it’s directly linked to my diagnosis. I have borderline personality disorder.”

“BPD affects everything,” explained Owusu. “It affects my relationships with people, friends, romantic, my sense of identity, all of these things. It just confuses everything. I can’t regulate my emotions, so it’s had a very negative effect on my life. I think the first part of healing was finding out what I had, so I’ve probably had this disorder since I was about 12 years old and been depressed since I was 12 years old.”

Owusu’s relationship with his mother remains a work in progress, and understanding her motives behind the decision to place him in foster care is still a point of contention. While he has a clearer picture of the challenges which underlined her choice, for him, it’s not quite enough.

“It doesn’t do anything to the pain. It still happened. I was still in care. I was still with my mum when I wanted to be with my other mum,” he said. “If I had stayed in foster care and never seen my biological mum again, at that point, I would not have cared at all. And I think it was hurting my mum at the time. Sometimes, even now, it hurts my mum."

In a world of hypotheticals and what-ifs, the idea of being raised in a healthy black household for those early years of his life isn’t something he’d ever fully considered until this interview.

When presented with the thought of it, he is able to imagine how, at the very least, his hair and skin would have benefited. “The comb that they used to comb my hair — it wasn’t even an afro comb,” he said. “I don’t even know what it is, but I would have sores on my head and my skin. I don’t ever remember it being creamed.”

Beyond the surface, however, he said the biggest impact could have been to his self-esteem: “I think my self-esteem may have been built up if I was around a black family, especially if we were a black family in that white area, because then I know they would [have] put more emphasis on me to believe in myself, [to not] let people talk down to [me] — just to make sure that I was prepared for the world outside.”

Even with all the love poured into him by his foster parents tucked away in idyllic Long Melford, he admitted they failed to equip him with the tools needed to navigate society as a young black man. “That’s one thing my foster mother didn’t do. She didn’t prepare me for the world, for the racism. I never heard the word ‘racism’ or the word ‘racist’ in our house,” he said. “I didn’t know what those things were until I was in year 6. I think all of it could have made a big difference.”

MoJo, 26, Lincolnshire (fostered from 1993–2004)

MoJo, a 26-six-year-old social media influencer and mental health advocate, isn’t a young woman who lives with many regrets, but over the course of revisiting the many twists and turns life has thrown her way, the legal case over who would have primary custody of her is still a heartbreaking situation.

“She fought so hard for me, and I feel so stupid for not choosing her,” MoJo told BuzzFeed News as she recalled how as a 12-year-old she was torn between her Nigerian birth mother and the woman who took her in and raised her and then fought for custody in court. She chose her birth mother and it’s a choice she has struggled to make peace with.

When MoJo recalls her early years, she tells the tale of how her Nigerian mother arrived in Britain in the early ’90s, met her father, and conceived her as part of a scheme to secure legal residency. At least that’s the version of events she has long believed.

After a failed attempt to place her with a Nigerian family in east London at 3 months old, MoJo was relocated to rural Lincolnshire in the north of England, under the care of a foster parent she refers to as her grandmother.

“My foster grandma states that she fell in love with me from the moment she had me in her arms,” she said. Her memories from that time are pieced together with notes from personal health records and what her grandmother has relayed to her.

MoJo is measured and protective when it comes to speaking about her childhood home and how her foster grandmother raised her, starting with her guardian’s conscious decision to have children she cared for call her “grandma” as opposed to “mum”.

“She made that decision,” she said. “Because all of the kids were going to go on and be adopted, and it would confuse them to go from [birth] mum to temporary mum to adopted mum. So she said, ‘I will be your grandma. I'm attached to you but it's still healthily detached.’ And I really appreciated and respected her for that.”

MoJo speaks passionately about her grandmother who she remains in contact with. “She's the absolute love of my life,” she said. She is my hope in a very dark and lonely world. Her voice brightens my day. I love her because she's taught me how to love freely, and I think that's what I'm able to pour from. Because I've seen it given freely, I will always give back.”

Even with all the admiration, there are certain realities of her childhood that MoJo refuses to repress. “Grandma gave me a good experience, but it was never what I needed,” she said. “Because I love her, I don't want to disrespect her at all.

“It was not meant to be her. It should have been my mum. Everyone gets picked up from school by their mum. I get picked up by someone who doesn't even fucking look like me, and so it will always fall short. And that's so hard to say because I am so majestically grateful. There's so much beauty in the story, but when I look back I was confused. I felt like I pretended so well. My personality worked against me. I'm so good at pretending and knowing how to smile that you don't actually see ... this is awful.”

MoJo said she was bullied as a child, leading to a severe identity crisis as she tried to make sense of her differences in a largely white town and within the household bustling with children who didn’t resemble her.

She said: “I always questioned my skin colour and so did people in school. I remember being bullied at about 4 or 5 and having to miss reception for a week.

“Grandma tried. She gave me treats and let me bunk off school and told me I was pretty and got me all the things in the Argos catalogue, but it just wasn't what I wanted. People wouldn't see it as racism because it's just kids ganging up on another kid, but it's because she's different. Why is she different? Her skin. So at the age of 4, I wasn't directly being called a nigger. No, that was later on.”

MoJo’s birth mother would make the trip to Lincolnshire to see her roughly twice a year. In her primary school years, MoJo would return to London during the major holidays. She doesn’t recall the trips as happy affairs. MoJo said her mother was verbally abusive, picking on her weight and the state of her hair. At 5 years old, she said she was forced to have her natural hair chemically straightened.

It was during these visits to London that MoJo said she was sexually assaulted by someone close to her and much older. The incident, coupled with her difficult time in foster care, would push her into a dark place. “When I was 8, I tried to hang myself from my bunk bed,” MoJo said. “I didn't get to play like normal. And grandma was so wishy-washy in her parenting.”

MoJo elaborated, explaining that when she had been racially abused, her foster mother would say things like “I've always thought your skin was beautiful, sweetheart, just ignore them.”

She felt that wasn’t enough to help deal with a child’s self-confidence. “That doesn't do shit. That doesn't do anything for you,” she said. “I hated my life and I despised it for a very long time, and I'm still trying to understand it now.”

The bustling household would be home to several children across the duration of years MoJo lived there, some of whom would return to their parents, while others would go on to be adopted, the revolving door of children while she remained. It made her feel “very unwanted”, she said.

“I'm thinking, if I'm in foster care, I must be getting adopted as well. Even though no one said it out loud, I had to be adopted at some point. Everyone else is in care. They seem to come and go, come and go, and I'm still fucking here. For 8 years, 9 years, 10 years, 11 years...the fuck?”

It was during her 12th year that her life would take the dramatic turn that she called “horrendous”. During a Christmas visit to her mother’s home in south London, it was decided that she would be staying indefinitely.

“She said to me, ‘You're too big, you've put on too much weight. You're not going to see your grandma again.’ I just remember falling to my knees and begging her, ‘Please don't do this to me. Please.’ I literally begged for my life because I didn't know [my own mother],” MoJo said.

In the years that followed, MoJo said her relationship with her biological family completely disintegrated.

MoJo’s struggles with her racial identity were not alleviated by her move to south London. Instead, the crisis deepened, and her confusion was quickly replaced with hatred. “Based on what the media had shown me and my experience of black people, I hated them. I really did.”

The 26-year-old began going to therapy in January this year. She received a preliminary assessment of “emotionally unstable personality disorder, which I didn't understand the symptoms as well as I do now”, she said.

“In psychodynamic psychotherapy, it's very intense. It's linking everything back to my childhood. It's very hard. Because as a performer of happiness, I don't realise how damaged I am sometimes and how vulnerable I am and what's still quite perverse and distorted in my mind because of my trauma.”

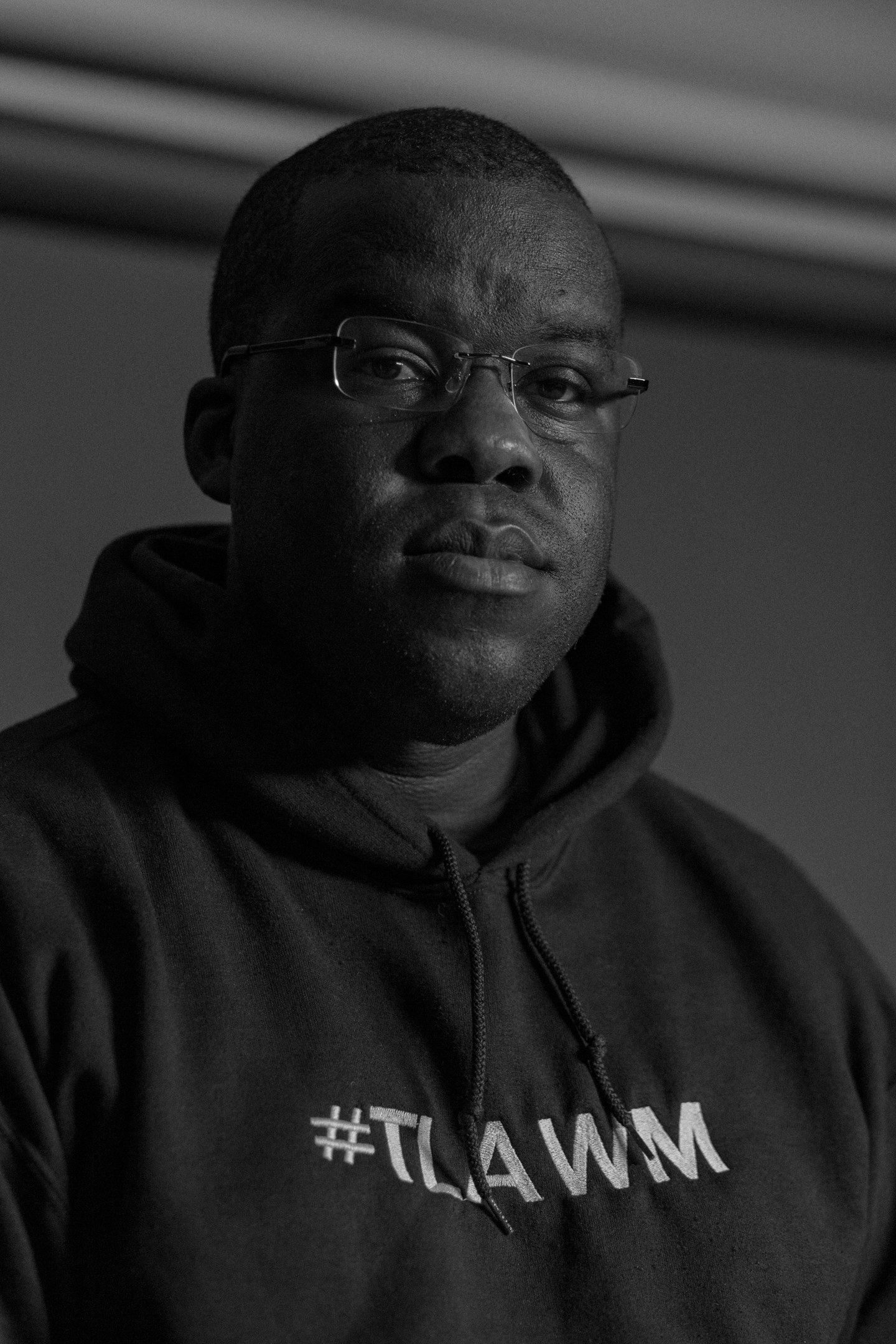

Nels Abbey, 39, Benson, Oxfordshire; Rugby, Warwickshire; and Derby, Derbyshire (1980–1990)

Nels Abbey was in foster care “practically from birth”, he told BuzzFeed News. Moving between three English towns, he eventually spent his early years in Derby. And what may have appeared unconventional to others was, for him, entirely normal.

“For a long time, I didn’t think there was anything strange about me having white parents. It was perfectly normal. Thinking back to that time, it was just the way it was,” Abbey said. “The same way in which anybody would view their parents is how you would view your foster parents when you’re born into it. Those are your parents. Mum and dad — for me as I knew them at the time — were a German lady and a white man of Scottish descent. They provided us a good life with stability and a happy home.”

Abbey formed a particularly good bond with his foster mum “more than I did even, for a long time, with my own mother, and it will probably be painful for my mum to read that”, he said.

Revisiting what he described as “the happiest days” of his childhood, Abbey shared how as a little boy with an appetite for Belgian buns he would become subtly aware of his differences on the doorstep of a bakery.

Aged 5, he was approached by a group of white teenagers hoping to find answers to a very peculiar question. “They were speaking in very sincere terms, and they said to me that they had heard that Velcro was made out of black people’s hair,” Abbey recalled. “I didn’t know what Velcro was, and I didn’t know what black people were. So I asked them, ‘What’s Velcro?’ And they showed it to me right there. And then, from that point, I just made the assumption that ‘black people’ is me.”

For a price, the teenagers asked a young Abbey if he would be willing to let them test out the theory by demonstrating on his own hair. “I was aware of the concept of money,” clarified the author of Think Like A White Man.

“I knew that I could get a little money from these guys and use it to buy myself a Belgian bun, which was my favourite thing in the world at the time, and so they brought out their tennis bags and they tried to put the hard bit of Velcro on my hair — but, of course, it didn’t really attach.

“You could feel the disappointment oozing out of these children as they walked away. And it wasn’t like these were kids who were doing this from a malicious perspective. It was like a science experiment, and as they walked away they left me with a bit of money. But they also left me with full awareness of what Velcro was and of the fact that I was a black person.”

As an adult, Abbey would grow to better understand the significance of his foster mother’s German heritage and how it enabled her to articulate racism to him in response to his treatment at school which often left him punished more harshly than his white counterparts.

“I was born in the ’80s, so 1945 was just 40 years earlier, which might seem like a long time but it’s really not. She was alive during the war era. She was young but she was very aware of what was going on. So the learnings of the post-war — particularly for the German population, where they had to confront this notion of what racism is and the impact it has — was clearly something she knew of.”

More than 100 miles away in west London, Abbey’s birth mother was making plans to bring together her children under one household. In one summer, his world as he knew it would be dismantled.

“I didn’t differentiate between the word ‘mum’ for both my mum and my foster mum. They were both just ‘mum’ to me. When I got to the age of 9 or so, we would then spend our summer holidays with our mum. I remember going to stay with our mum this particular summer. As it was about to end, my foster mum was supposed to come and pick us up. As I remember it, she called to confirm the details. And my mum said to my foster mum, ‘It won’t be necessary for you to come pick the children up anymore. I’ll take things forward from here with my children.’”

The news came as a shock for Abbey and created a “very traumatic experience” as he said his final goodbye.

“I remember my foster mum got on the telephone, and she was crying her eyes out. I was crying, but she was crying more. And she kept repeating, ‘They’re trying to take you away from me. They’re trying to take you away.’”

“When she put the phone down, I kept crying for a bit of time. And one of my aunts who was there looked at me and said, ‘Why are you crying? What’s so bad about us? Why don’t you like us? Why don’t you want to stay with us?’ And it did make me think, what is so bad about my mum or staying with them? And I kind of stopped crying from that point, and part of me almost felt as if I had a responsibility to not cry for my foster mum or to want to go back to my foster parents by virtue of the fact that it was kind of offensive to my actual parents. And to some degree, I suppose it is, in retrospect.”

Their tearful goodbye over the phone would be the last time Abbey spoke to his foster mother, and their blunt separation would be something he never properly dealt with: “You just move forward with life,” he added.

“My mum to this very day calls her ‘the nanny’. To a certain degree, I don’t really say anything about it because it’s a very complex situation. To my mum, that’s what she was. She was just someone looking after the children, but to us it became more than that. It was deep.”

Life in west London would come as “a big culture shock,” for the newly relocated Abbey, who had become a full-fledged member of the club of then-beloved children’s presenter Rolf Harris, who hosted the show Rolf’s Cartoon Club. (Harris was convicted in 2014 of sexually assaulting four underage girls.)

“Week one, it was all good. Everyone took a liking to me, and we were all cool. So week two, I thought I’d up the ante and see what these guys were into, and I made the stupid mistake of wearing my Rolf’s Cartoon Club badge to school. I didn’t know how unhip that was, and everyone started ripping into me. And I realised that London was not this centre of innocence that the countryside was.”

Similarly, Abbey came to realise how his Nigerian heritage further tanked his social capital in the playground and forced him to take extreme measures as an act of self-preservation.

He said: “Me and my Rolf Harris badge and my Nigerian heritage quickly became sources of ridicule. Luckily I had an Anglo-sounding surname, so I quickly lied and went into the closet. I said that I was from Barbados or something, and everyone believed me. And I stayed in that closet for a few years.”

Abbey would spend a further two years in west London before another dramatic change meant he spent most of his teenage years at a boarding school in Nigeria, where he received a baptism of African culture by full immersion. It was during this period he would receive the heartbreaking news that his foster mother had died.

On the news of her death, he said: “I think my foster mum taught me what love meant, and I really did feel loved. She wasn’t perfect, but I do know she loved me very dearly. I really did feel that — particularly when I think back to when I was in Nigerian boarding school and I found out she was dead. I found out in a letter and I stayed up all night long crying.”

The proud British Nigerian spoke with gratitude for the different cultural lanes he’s lived in. He credited both sets of parents for instilling a strong sense of values and moral good.

“The life that I have lived with foster care, with my mum, with my dad, with boarding school and everything else,” he said. “I cannot think of a different life, because that was my normality.

“Don’t get me wrong, when I speak to other people it's now that I realise how crazily abnormal that was. The foster care process, I am a product of that environment. That environment helped shaped me into who I am today, and I'm very grateful to my foster mum and dad and of course my parents too.”

Gina Knight, 36, London (fostered from 1984)

Gina Atinuke Knight was born 10 weeks premature at a private London clinic. Shortly after her birth, she and her Nigerian mother travelled to Nigeria for a short stay. They returned to the UK when she was 11 months old, and she was placed in private fostering by her mother, who “never came back”, Knight said.

What was designed to be a temporary arrangement became permanent. It would become a defining feature of Knight’s childhood and forever change the mother–daughter bond. When Knight was 6, her case was brought before the courts, where it was decided that she would remain in the permanent care of the family she had lived with since she was an infant.

From what she can recall, Knight said, “The judge determined that for my benefit, because I had been raised by these people for six years, that the best place for me was with them.”

She continued: “As a young girl I obviously thought that my mum didn't really care. … There was no reason for her not to keep me. She wasn't poor, she wasn't unable, she wasn't so very young. She was capable of taking care of me.”

As an adult, and a mother now herself to two children, Knight said she has come to understand the challenges that may have explained her mother’s absence. “As time goes on and you figure out all the aspects of the story, you kind of think, ‘Oh, well, actually that might've been the reason for that,’” she said.

The feeling of abandonment complicated their relationship. Even when her mother did reappear, their encounters would be cold. “I would see her every now and again,” she said. “She would visit me, or she would send an uncle or an auntie to visit me, but I was always very standoffish because I was a child and then a teenager, so I was like, ‘I don't really want anything to do with you.’"

Knight said that today their relationship is civil, but they don’t really talk.

Knight was raised in multicultural southeast London, an important detail that offered her a strong sense of identity even in the midst of an unorthodox home life. While she was the “odd one out” inside her white foster family, the community she lived and socialised in reflected her cultural identity.

“I was always very aware of being different,” she recalled. “A lot of people ask, ‘When did you realise that they weren't your parents?’ There was never any doubt, for obvious reasons, and also I always felt like I wasn't really their child, I was just sort of like...an extended house guest for a really long time.”

Her foster father, she believes, tolerated her presence, but rarely expressed any affection. “It wasn't a loving relationship. It was just more of a financial transaction. I personally felt at the time, and probably still do, that I was a bit of a burden on him,” she said.

She is cautious when speaking about her foster mother who would become her primary caregiver until she died when Knight was 21 years old. “She was quite a normal mum, very much a mother bear–type,” she said. “She was protective of her children, and that's what I remember about my mum. She was very loving and protective of anyone that she was taking care of. She was very loyal, was very protective of them.

“But then she was also quite oblivious as well. So she would almost get on with her everyday life, I think she just didn't really... I don't know. I'm not going to talk about her anymore because it makes me a bit sad, so I'll leave it.”

Knight did experience some frustration of being raised in a household where the only person who appeared to validate her difference was herself. “I just don't think that a lot of these working-class people had the capacity to articulate what we would go through as black children being raised by white people,” she said. “It's just not something they could fathom in their head.”

She went on: “There was no differentiation. The differences were obviously there, but there was no kind of acknowledgement of those differences. In turn, you don't really know how to navigate the feelings that you're having because they're not being acknowledged by the people around you.”

As a result, Knight said, the complexity of her living arrangement meant she did struggle at times to really connect with both her black and white friends. “In essence you are transracial, and I hate that word, but it's a very difficult space, and I don't think at that time there was enough knowledge,” she said.

She is critical of an entire system that left her with little say in how she would be raised and even less support about how best it could be done. “Those social workers should have done more to prepare [the foster parents] for what I would go through growing up and how I would feel and ways in which to help me navigate that, and I don't think that was done at all,” she said. “Especially not back then. That's just not something that was discussed.

“I don't think they were pulled aside and asked, ‘Do you understand what you're sort of going to be doing going forward? That you're going to be looking after someone who is not the same race as you. Do you know what kind of impact that's going to have on that child's life?’ I don't think those conversations were ever had.”

Knight’s experiences and discovery of other black British adults who were also in the foster care system at that particular point in time stirred her into building a private online space for that community. Reflecting on some of the “horror stories”, she is equally critical of the parents who volunteered their children as she is of foster parents and social workers who don’t consider the damaging impact transracial fostering can have.

“I just don't think that that generation of parents thought it through and thought of the dangers that could befall the children in some of these circumstances,” she said. “Not just psychologically, but physically and emotionally. It was a very dangerous thing to do because people have put advertisements in papers, and you don't know these people. You don't really know what they could be doing to that child.”

Knight said she could never imagine putting her two daughters in the situation she was put in and finds it hard to forgive the decisions her biological mother made.

However, becoming a mother for the first time in 2012 was the impetus to seek peace. “I just decided that obviously I needed to know certain things, because I'm about to have a child, so I need to know about my family history,” she explained.

Today, Knight admits that she still sometimes feels “out of place”. But through her skills as a hairstylist, she has been able to grow and nurture relationships with other black women. “I'd never really connected with anyone, so for me it was all about hair. And that was the only way that I could find to talk to other black women and form friendships,” she said. She now runs an award-winning wig business.

Knight, a mother of two, is fiercely protective of her own little family and is a staunch believer that when it comes to caring for children of other ethnicities, there is no room for so-called colour-blind politics.

She urges prospective parents for black children to “make sure that they're doing it for the right reasons”.

“I think that if you're not 100% committed to antiracism, then you have no place to really be adopting outside of your race, or even adopting at all — because you should be antiracist,” she said. “If you think that all a child needs is love, and that's it, that they don't need any sort of other tools to be able to function in life, you're probably wrong.”

For Knight, the worst thing a parent can do is to say that they “don’t see colour”.

“That's bullshit, and it's actually detrimental to that child's wellbeing that you don't see their race — because that means you don't see them,” she said. “I think you just have to be aware of race and not try and brush it under the carpet and try to be in this little colour-blind bubble ... because this utopian world just doesn't exist.”

David Gorgeous, 39, Brighton, East Sussex (fostered from 1980–1990)

If you ask David Gorgeous, he will tell you that he had three mothers.

“It was quite funny to feel like any mum that I showed more love to, I would be hurting the other mothers,” he told BuzzFeed News. “It's just that I love them differently because they're different people. What I can speak to one foster mum about is different to how I would approach my biological mum. I wouldn't tell my biological mum everything, but I would mostly tell my foster mum everything because the way she receives information is made different.”

Gorgeous, as one of the thousands of West African children farmed out to white working-class families, characterised the three matriarchs and three very different households from his childhood.

“I moved from the first home which was free and open, to the second home which was a bit more disciplined and more about education, to my Nigerian home, where it’s ‘Don't talk unless you're spoken to, be respectful, and listen to your parents’,” he said.

Appeasing the adults in his life and the weight of loyalty would create a splintering effect which the 39-year-old experiences even to this day.

He said: “I had to learn how to be totally different people. Even now when I go back to see my foster mum, ex-partners have said to me that they can see a total difference.”

A self-described comedian, Gorgeous works as a makeup artist. His story of being farmed begins in early 1980s Brighton with a couple who had no children of their own but had opened their home to other black children before fostering him. While he can speak at great length about the open and progressive environment they created, it was in that household where he was sexually abused by a family friend.

“I never went into detail, and that person passed away,” he said. “I guess that's something I will always keep private because there's no point in time that they’re going to face justice. It was a sick man who needed help. I was extremely young. Only as an adult I figured out what the hell was happening.”

Nevertheless, the experience still affects him. “It affects me and my relationships,” he said. “How close I am to people and how close I let people in — I say I'm an open book but with glued pages.”

At the age of 6, he was relocated to a second home in Brighton to join his biological brother; however, a stark difference left him unable to adjust and longing for his previous family. “They were lovely, but I just didn't settle there,” he said. “It was mainly because I was so used to my foster mum. There was a lot more rules than I'd ever had before. My second foster mum had five children of her own, then me and my brother, so it was very spread.

“I went from being the sole person of attention to a pecking order in the second foster home. That took me a while to get into, and so I withdrew within myself a little bit more than I had done in the first foster home.”

When it came to identity, for Gorgeous, coming into manhood took precedence over any other descriptor; for his blueprint, he looked to his first foster father. “I was taught to be a man first before being black, white, or anything else,” he recalled. “When my foster father would dress up in a suit, I would dress up in a suit, like at special occasions. He was teaching me how to be a boy first and then a man, rather than differentiating by colour.”

It was his first foster mother who first spoke to him about race.

“As a child, I didn't identify with black or white, but my foster mum was very clear: I was her little black boy, so she was very much establishing me as a black boy,” he said.

And nothing punctuated his blackness more so than the outside world. Gorgeous recalled his time in primary school, where he would be called every name but the one his parents actually gave him.

“I would always hear ‘nig nog’, ‘golliwog’, the n-word. I didn't know what those names meant. I didn't know why I was being called those names, and for some reason ‘golliwog’ really upset me. I don't know why, but it really did. They were calling me a name which wasn't my name, and they were being mean, even down to adults calling me ‘golliwog’.”

His foster mother’s response was to reassure him and attempt to translate the way in which racism operated: “She tried to put me at ease as much as she could and tried to make sure that I felt comfortable in my own skin. She made me aware that we are different colours and some people aren't so welcoming to different people of different colours. So she tried to put it in as simple terms as possible for me.”

In contrast to his first foster mother, his Nigerian mother, whom he described as “strong” and “bold”, kept in regular contact and routinely took sons for the summer holidays. For that, Gorgeous considers himself fortunate. “She very much stayed involved. We weren't just left by her,” he said.

With his biological father back in Nigeria, where he had started a new family, his mother was left as a single parent, working in London to ensure that the families fostering Gorgeous were paid on time.

By the time Gorgeous was 9, his fostering experience would come to an end. He went from Brighton to Britxon, in south London, within walking distance of the now-iconic Windrush Square. “I went from being surrounded by white people — the only black in the village — to being literally surrounded by black people. In school, understanding there was Nigerians, Ghanaians, Jamaicans — and everyone wanted to be West Indian at that time as well. So it was a culture shock and a half because I was a very British child. I wasn't used to that.”

The adjustment would be better described as a free fall, with very little explanation or support for the transition — all aspects that Gorgeous believes are “harmful”.

“You're not explaining to [children that] they're just moving from home to home. There was no social workers involved. There was no psychological support. It was just literally move, move, now you're back with your Nigerian family you should be a Nigerian boy.”

By the age of 13, Gorgeous found himself embarking on another journey. On a family holiday to Nigeria, he suddenly found himself being fitted for a school uniform. “The day that me and my mum were supposed to come back to London was the day they dropped me and my brother off for boarding school,” he said.

Despite his protests, he spent two years at the school becoming familiar with his Nigerian heritage.

Gorgeous now sits on a panel for foster children, where he hopes that his experience outside the formal system can be used to improve the experience of England’s thousands of children in need of homes. In England, children of black and mixed children are more likely to be placed in care, with the majority of looked-after children being survivors of abuse or neglect.

Regarding his experience of being raised in a white household, Gorgeous has no immediate objections to transracial fostering, but he is mindful of what is at stake. “I wanted to give back and do something, and this comes across so much in terms of matching the keywords,” he said, “so you have to try and match a child with familiar cultures, religion, race.

“Sometimes a child just needs a home, and this is how I believed for many years, but being on the fostering panel is like feeling that sometimes if you don't match correctly it can go so wrong.”

Reflecting on his life's trajectory as charted by his mother’s choice, Gorgeous reserves judgment and instead poses a hypothetical question: “What could I have expected her to do? She chose the best decision she could based on her circumstances. At the same time, there's always going to be scars and things that happened that we've had to overcome from those foster homes.” ●

UPDATE

A quote from this story was removed after publication to protect the privacy of a family member.