In 2013, Kristin Beck became the first former Navy SEAL to come out as transgender, which instantly placed her as one of the most high-profile figures in the meteoric shift in the national conversation about transgender rights. In person, she is instantly open and friendly, happy to talk about just about anything, but her voice hovers just a few notches above a whisper and never any louder, and her demeanor can at times read as diffident, almost shy. In fact, if you had not heard of her, you could be forgiven for never guessing she is an activist who regularly travels the country for speaking engagements, let alone a decorated veteran with 20 years of some of the most grueling combat experiences a soldier can have.

But, according to Beck, there is one thing you would definitely know about her upon meeting her for the first time.

"Imagine me walking down the street," she told BuzzFeed in March at the SXSW Film Festival. "It's obvious. It's like, Wow, there's a dude in a dress."

It is one of several eye-opening, unexpected things Beck said over the course of a far-ranging interview after the world premiere of Lady Valor: The Kristin Beck Story, the feature documentary about her life after coming out as transgender. (CNN will debut the film, directed by Sandrine Orabona and Mark Herzog, on Sept. 4 at 9 p.m. as part of its CNN Films unit.) From her views on certain central elements of trans representation — such as mis-gendered pronouns, and before-and-after portraits — to how much she's learned about her journey from talking with the Taliban, Beck is definitely fearless about challenging anyone's expectations about who she is, and what she believes.

View this video on YouTube

What was it like watching the film for the first time with an audience?

Kristin Beck: I saw it one time before in a very private screening. I was still kind of in shock watching it. I think I'm a lot prettier in real life (laughs). I think that's what everybody thinks. I'm like, Oh my god, I have to lose some weight. I have to do my makeup. I gotta do my hair. My hair sucks. All the little things I would pick at myself, and you see it up there and it's on there forever. It's scary.

One of the things that struck me was how much footage there was of you before you started your transition, especially of you as a SEAL. There is a growing awareness that fixating on how a trans person appeared before transitioning is problematic, because it's not how that person self-identifies. How did you feel about that part of the film and the process?

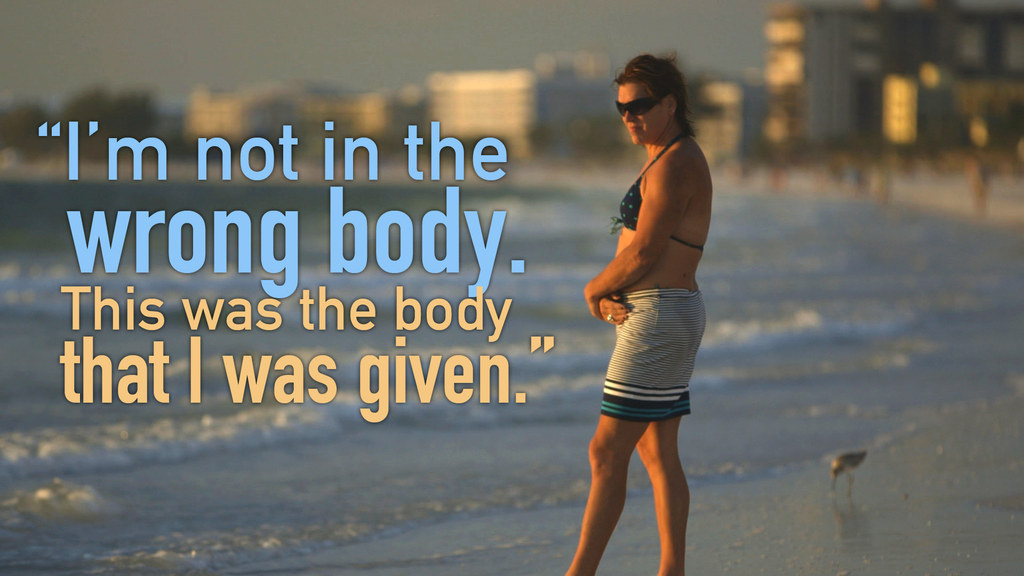

KB: That's something that comes up a lot when everybody says I was "born in the wrong body." It's a very common term that people say. I'm not in the wrong body. This was the body that I was given. One gentleman asked me about my knee and some of my injuries, and I say, "It just — it hurts. And I deal with it. It's painful, and I deal with it. And I just try to do the best I can from that point."

It doesn't totally match up with some of the way that I feel — it gets religious if I say "soul" or if I say "spirit." It's not religious. I don't know what it is. But there's something inside that this is what I've got, and I have to deal with it. And my life prior, as a Navy SEAL, it's still part of my life. I don't want to deny it and say that I hate it. There's a lot of things I'd like to change. And now I'm doing that. But for me to hate that, for me to turn it all off and say, "I never did that," and totally black it out would be a disservice to my journey.

Even the sucky parts made me what I am right now, you know? I just want to drive on, and give a little tribute to that. There's always painful things in everybody's lives, so don't totally turn it off and deny it. Use it and try to be better. That's what I'm trying to do.

I talk way too much, I'm sorry.

It's OK! So when people write stories about you, and use before-and-after photos, how do you feel about that part of it? It's not you telling your story, or you working with someone to tell your story, but someone else that you have no connection to doing it.

KB: Well, it's still me. I think they misrepresent it a lot, and they try to just show that dichotomy in my life. That's why my earrings are a skull and a peace sign. I'm a little bit complicated. It's something that I accept. I just hope they do it the right way. A lot of times they do. I don't know. It's odd sometimes when I see it. I hope one day they start focusing on the goodness of the whole thing instead of stark contrast. I mean, the contrast is pretty wide. But I hope that people look at it and go, [If] I'm able to get through this huge, huge contrast of life, they can get through these little mini contrasts of life. If you want to dye your hair purple, man, go for it. It's not that big of a deal. If you want to change your job, because right now you're a reporter and you always wanted to be a schoolteacher, that's not as big of a jump that I'm making right now. So if they want to use that contrast to say that as humans we can do a lot of cool stuff, your little contrast, your little change, your little micro-jump, it's not that big a deal. So go for it.

If the world were drastically different, would you have wanted to be out as a trans woman in the military, so that those photos of you when you had your military service would reflect how you are today?

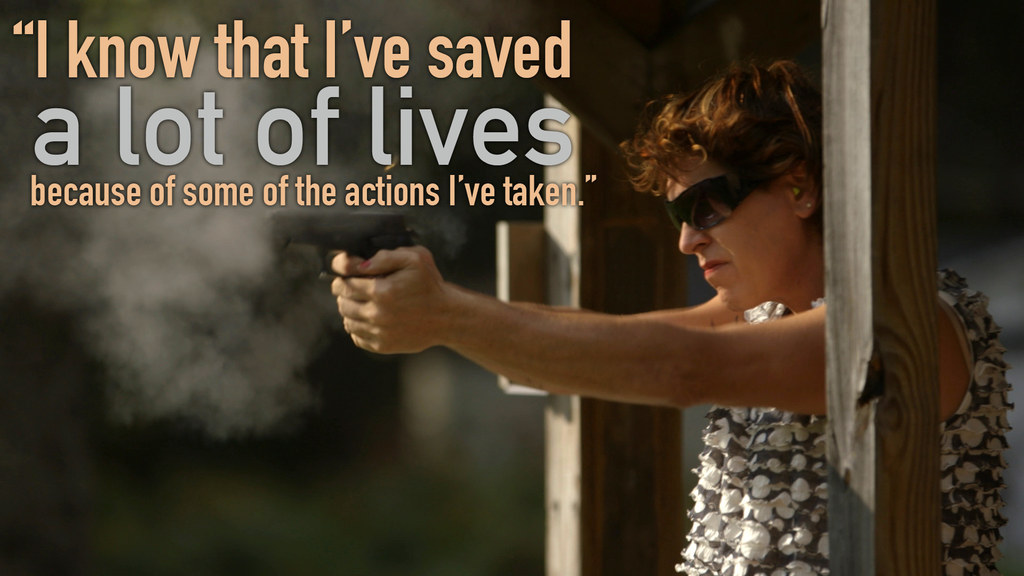

KB: That's an interesting question. I mean, hindsight's 20/20, and I would love to look back in time and say, "Yeah, I've wanted to transition since I was in third grade," but then I would've missed out on [my Navy SEAL career]. And I know that I've saved a lot of lives because of some of the actions I've taken in the middle of some pretty tough circumstances. (Pauses) I don't know if it would've been a better life, a worse life, a different life. I get emails all the time from a lot of young kids right now that are going through a lot of these struggles. I get suicide letters that they're right on the edge. The little glimmer of hope that I can give to a few of those kids — I'm writing back to them, trying to give them some hope, and trying to point them in directions, like to the Trevor Project. So what would've happened to all of those people? For me to wish I did something else — yeah, I wish I did, and I don't know how it would have affected my life. Would I have been happier? I think so. But I can't change what I have right now. I'm going to do the best with what I have.

From observing the documentary, it seems like you had to retire because you'd sustained so many injuries that it just was not possible to be a SEAL anymore.

KB: Well, they would have medically retired me. I could have hung on for another 10 years and gotten 30 years total, which would be a better retirement and everything else and blah blah blah. But I hit my 20 years, so I had the capability to retire. I was in the field, like, four months before that, and I was in firefights. So I'm a 45-year-old, very broken person, running around Afghanistan with a bunch of 25-year-olds. I was a little slower and I wasn't quite on my game. I could definitely look at myself and go, Man, I don't want to be a danger. I don't want to be there and put my buddies in danger, or be not at the top of my game.

The thing is, though, a lot of my other game is way, way better, as far as me interacting with the tribal leaders, the Mujahideen, and the big commanders. Even when I was sitting across the table from the Taliban, which I did on numerous occasions, I was able to do that on a level that a lot of those young kids could never do. So that game was stepped way, way up.

In order to be that person who is sitting across from the Taliban, I would think you had to subsume an enormous part of yourself.

KB: Yes. I had to put the American flag away sometimes. Like, even when I'm saying I have to put [my] womanhood in a big bottle, for me to sit across from those guys, I had to take the American flag and stick that in a bottle and cork it, and try to come across to them as just a human being trying to find a peace. Some of their belief systems and some of their passion — I friggin' love that. Those guys are very passionate, but a lot of times, their passion comes off in a radical, fundamentalist, destructive way.

The largest statue of Buddha was carved into a giant mountain in Afghanistan. The Taliban put explosives and blew up and destroyed the largest Buddha in the world. It was like, Man, you guys could have done so much with that one statue. You guys could have opened it up, and had all those Buddhist pilgrims coming into your country. If you guys are the path to enlightenment as Islamic leaders and you have such a light to your religious journey, all those Buddhists and everybody coming to look at that [statue] would see what you guys are up to and how awesome you guys are.

This is something you would be saying to them?

KB: This was something I was talking to these guys about. Yeah, it would piss them off a little bit. [I would say,] "It doesn't have to be destructive to everybody else for you guys to have a good journey. You guys would actually have people coming over your path, if guys were constructive about it."

I was a big-bearded warlord myself, with a lot of people around me. And I had a lot of the Mujahideen that actually liked me and respected me. These are the guys who were fighting the Russians, you know, 30 years before. Those guys respected me, and they're sitting on my side of the table talking to the Taliban.

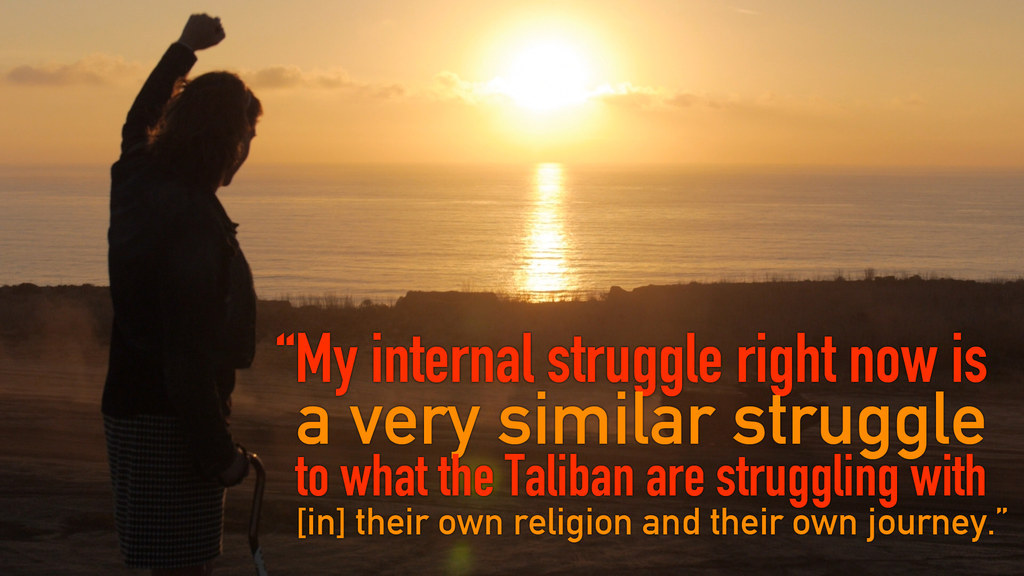

It feels like what you were saying to the Taliban is almost similar to things that people who are dealing with issues of personal identity tackle.

KB: Very similar, yes. My internal struggle right now is a very similar struggle to what the Taliban are struggling with [in] their own religion and their own journey, and what's the right way to do it? Do I have to destroy my own self to continue a journey into something else? I don't think so. I think it can be constructive. I think it can build on what I've done in the past. I can build on what I've been given. I've learned through war and hardship and my own internal struggles, and my external struggles. I've had my friends die in my arms in the cauldron of battle. Do you have to go through all these experiences to understand this? I don't think so.

The film opens with what looks like a support group or a gathering of veterans who are also trans.

KB: It's a conference, and it's just the random people who showed up at the conference. If you take any group of transgender people — let's say there's 100 transgender people in this room right now — out of that 100, 50 of them would have had military service, or more.

Fifty?

KB: Fifty out of the 100. Fifty percent out of any community that you bring a bunch of transgender people into the room. Male and female, you're going to find 50% of them are military.

So that opening segment was just a conference of transgender people, at which there happened to be…

KB: There happened to be that many military folks.

Why is that?

KB: It's that escape into hyper-masculinity. If you're a female-to-male transgender person, it's that escape into a masculine world where you can still live your life, and they actually like the fact that you're somewhat of a masculine woman. They're like, Yeah, rock on! So you can still live in a masculine world in your female body. That's for the female-to-male transgender person.

And for male-to-female like myself, we're able to escape into a world where we try so hard to bottle it up. I think it's been that way for a lot of years. We try to escape or cover it up or live in an environment where we can just bottle it.

There's a long stretch of the film where you're with your family, and they use male pronouns when referring to you, pretty much exclusively. There's that great moment where your father apologized and used a female pronoun for the first time.

KB: (Smiles) It was the first time. And I can't believe they got it on film. It was the first time he's ever said a female pronoun to me.

Do you think the camera contributed to that?

KB: Not a bit. Everybody kind of forgot they were there. We just started hanging out as the family.

You've said sometimes people use male pronouns in a derogatory fashion, and sometimes it's just a learning curve. Some trans people feel very differently about that.

KB: You're talking about, like, Janet Mock and Laverne Cox and all the other ones that get so angry and so militant about it.

In a way, yes.

KB: I think it's a shame that they do that. I mean, there is a learning curve. And there definitely is the derogatory [usage]. People are going to start being more compassionate towards that, but you can't expect everybody to overnight. How long have [trans issues] been in the media, on shows besides Jerry Springer making fun of it? Laverne Cox and a lot of people are really breaking through, but until two years ago, it was all "funny" and derogatory and kind of mean and really messed up. So do you expect everybody in two years to kind of just flip that coin over?

So I'm going to be a little bit patient. I know when it's derogatory or not. I know when somebody just mis-states, and they still see the guy in me. It's a bummer that they can't see past this shell, and they still use that male term, but it's OK.

There's a moment in the film where you're visiting a close family friend, and she's using all the right pronouns, and she's referring to you as Kristin. And then, at the very end, she breaks down crying and says, "Thank god he came back alive." It just was so telling that she's working very hard, but there's this sense of I knew this person in this particular way, and when I get more emotional about it, my thinking reverts back.

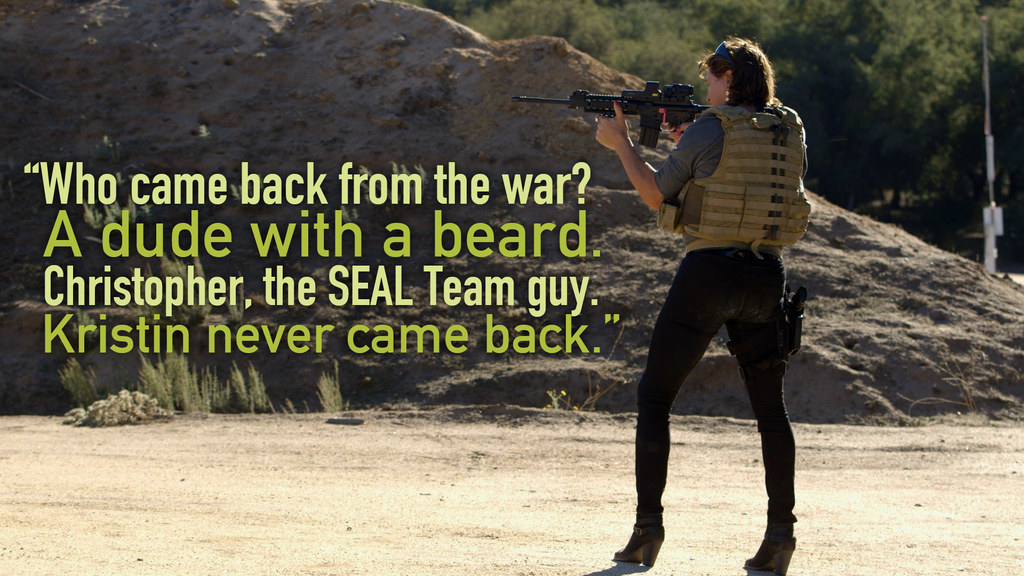

KB: But then again, think about it from her point of view. Who came back from the war? A dude with a beard. Christopher, the SEAL Team guy. Kristin never came back. So if you look at it some different ways, it really was him coming back alive. So she used the proper pronoun. You know what I mean? Kristin never came back from war. Kristin was never a SEAL.

I would think that there would be some trans people who would disagree with you, who would say you were always Kristin…

KB: I was always Kristin.

…and were always a woman.

KB: I am.

So from that perspective, wouldn't it be correct to say she came back alive?

KB: I have always been Kristin. I have always been this. This has always been me, right?

Right.

KB: But I was also that Navy SEAL, and I was also that guy. So for [my friends and family] to mix it up — that's why I think that militant mis-gendering and all the other stuff, it's like, you can't be that offended about it. It's going to be something people are going to grow through. And actually, if you look at it, if people use both of them, it's kind of like, Yeah, rock on. I am that whole person. I am that yin and yang. It's so confusing to some people because I blur those lines. Maybe we need a new pronoun, and we need to take the emphasis off that pronoun. Maybe I'm both. I don't know. Do they know? Do the militant mis-gendering people know if we are really male or female? I think [they're] doing a lot of presumptions of themselves. (Pause) I don't know! (Laughs) Can you answer me that riddle?

Well, I'm certainly less qualified than you are to answer it.

KB: This mis-gendering thing is a huge controversy. There's so much controversy surrounding all of this, when you get down to it, almost like when I'm sitting across from the Taliban. I can make everything very angry and very controversial and very militant and very "you do it my way!" It's America running Afghanistan and saying, "You must be Christian! You must do this!" Well, I don't really think we did that when we were over there. We're just saying, Hey, you guys, chill out. You don't need to go around the world, doing all this stuff. Just chill. If your religion is that awesome, then people are going to come to it in a peaceful way.

It's the same thing with [trans issues]. So my attitude is like, Yeah, they're going to get it. They're going to figure out, and stuff is going to get better. I'm going to give everyone a little bit of time. The Herzog group [one of the producers of Lady Valor] — they would mis-pronoun sometimes. And I would say, kind of joking, "Hey, look, you see this? Does this look like a boy?" (Shakes hands around her face) And they'd go, "Oh, OK!" If you do that a couple times to people, they never mess it up again. You know what I mean? So instead of poking somebody in the eye and punching them in the face, I just go, "Hey man…" It takes a while. This is not easy. I try to make them understand it's like a respect thing. You see how I'm trying to present and you see all the effort I'm putting into this. I just say, Hey, can you give me some respect? Please respect me.