The government is planning legislation to force some companies to reveal their pay gaps between men and women.

Under the proposed laws, companies with more than 250 employees will have to publish the difference between their average male salaries and their average female salaries.

In an article for The Times published Monday, David Cameron said the move "will cast sunlight on the discrepancies and create the pressure we need for change, driving women’s wages up".

Exactly what this entails is still undecided: The government has launched a consultation and the details will be worked out after that has finished in September.

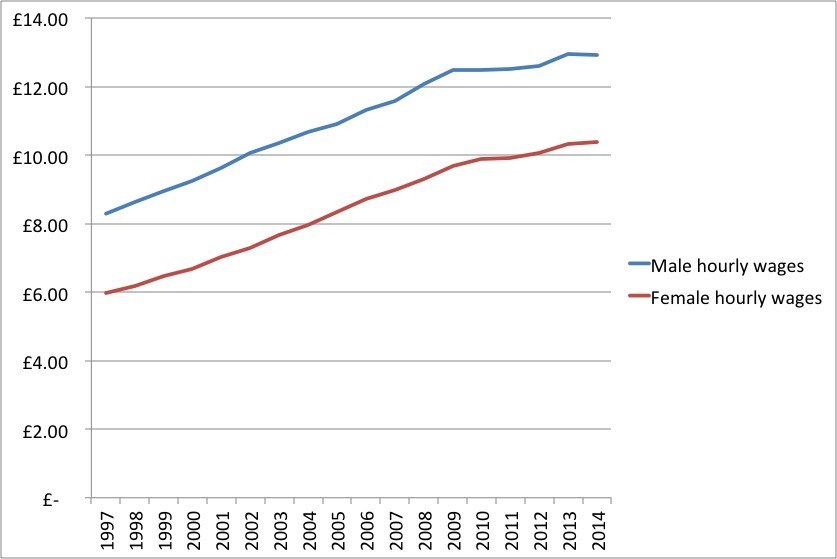

If you look at the median hourly wages of men and women in Britain – compiled by the Office of National Statistics – it's clear that women earn less.

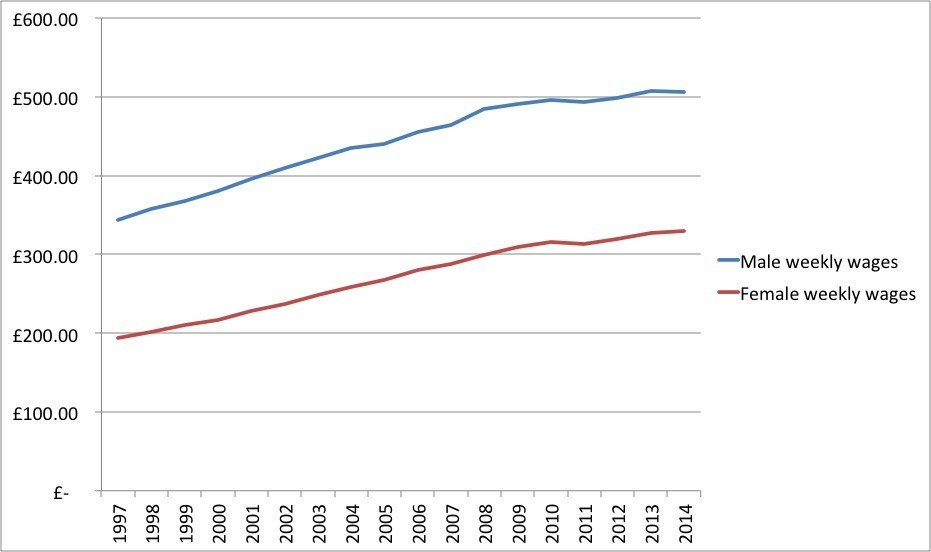

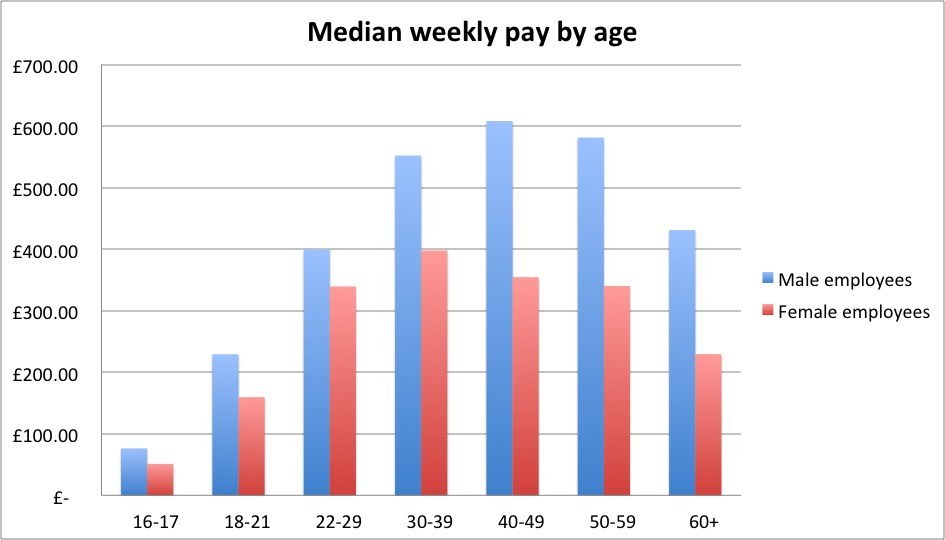

It's even more obvious when you look at weekly wages, because women are more likely to work part-time.

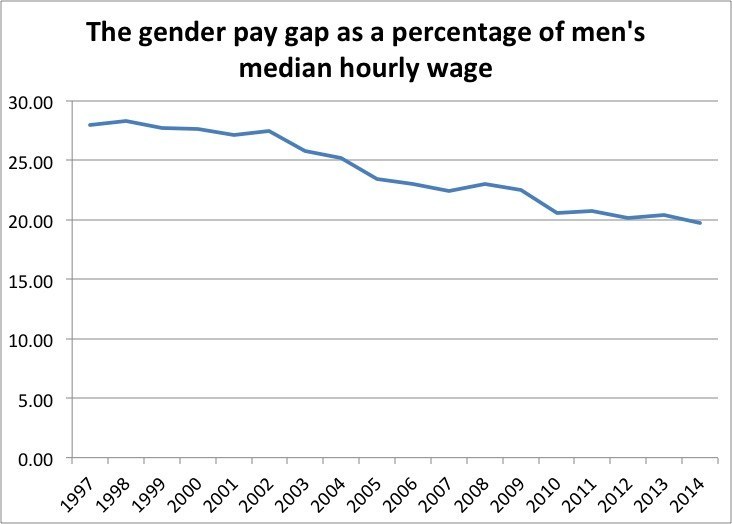

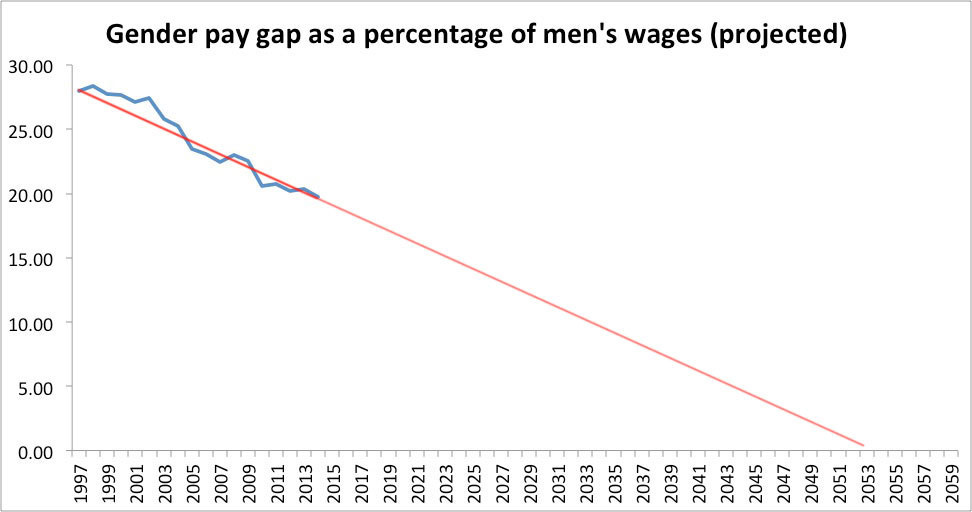

The gap between men's pay and women's pay is dropping – but the percentage is still significant.

Still, some people argue that the gender pay gap is a myth.

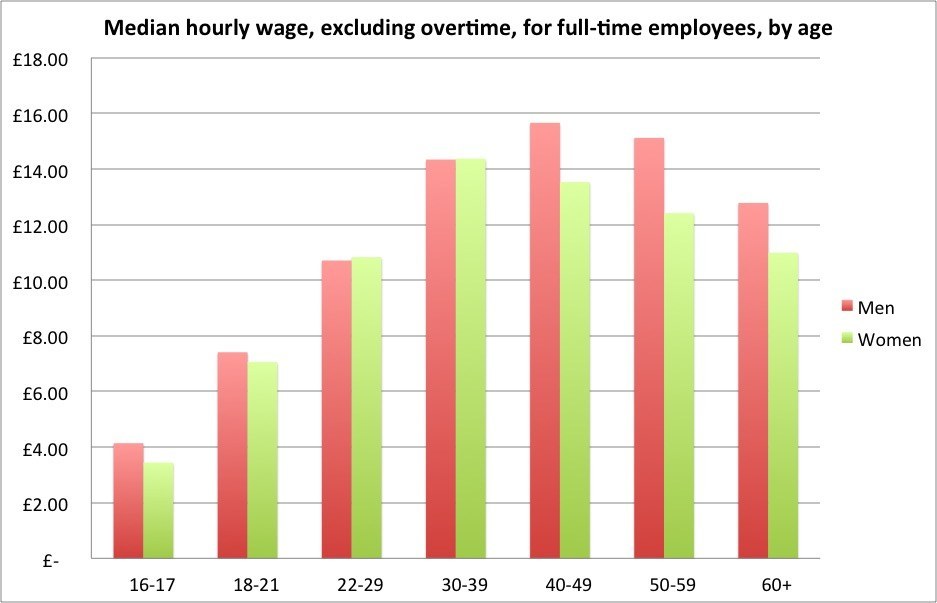

The Spectator and libertarian think-tank the Adam Smith Institute claim that women in their twenties and thirties earn more than their male counterparts.

But it's not – there's only one very specific metric in which women are paid more.

Women in their twenties and thirties who are working full-time earn slightly more per hour than men in their twenties and thirties – so long as you exclude overtime pay. If you change any of those specifications, you end up with a different answer.

For instance, if you look at men and women's weekly pay, men earn more, from their first job right up until retirement.

This is because men are more likely to work full-time, and to work long hours. The only way you can make it look as though young women earn more than young men is if you look at hourly wages of full-time employees without overtime.

So women really are paid less than men. The question is why, and what, if anything, can be done.

There are various reasons women get paid less than men in the UK. One is childbirth.

Women are much more likely to take time out from their career when they have a child. That's one reason behind the drop-off in women's pay when they reach 40. This means that they lose a few months of their career, but there's more than that. According to a report by the Equality and Human Rights Commission, mothers are likely to take part-time jobs and travel shorter distances to work, which limits the jobs they can get and therefore their pay.

This is sometimes presented as women "choosing" motherhood over a career, but it is worth noting that most men don't choose not to be parents; instead, fatherhood is subsidised and supported by the sacrifice of women's careers.

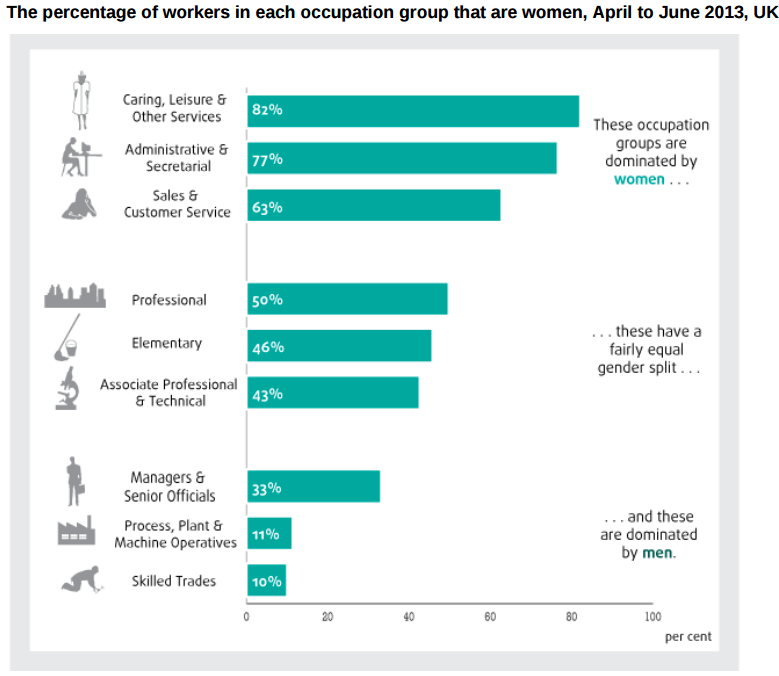

There's also the fact that women tend to work in less well-paid positions.

According to a report by the European Commission, the sort of work that women tend to do is often less well-paid, such as the public sector or the "caring professions". Men in similar jobs generally receive similar salaries, but fewer men do those jobs.

Helen Wollaston, the director of the WISE Campaign, which seeks to encourage women to join the science, technology, engineering, and maths (STEM) professions, told BuzzFeed News: "Women are concentrated in jobs that are less well-paid. That starts all the way back at subject choices at school."

And, of course, there's outright discrimination.

"There's a tendency, sometimes unconscious, to reward men more for their work," says Wollaston. "This might be because men are more aggressive, more willing to seek a move or a pay rise."

Discrimination starts from an early age. A Harvard Business School report found that even in preschool, teachers devote more attention to boys. Boys get more praise than girls at school, and are more likely to be asked to answer a question if they raise their hands at university. In work, women who are more assertive get more negative reactions than men do, and people are less likely to pay attention to them. If men are more aggressive and assertive about pay, this conditioning surely plays a role.

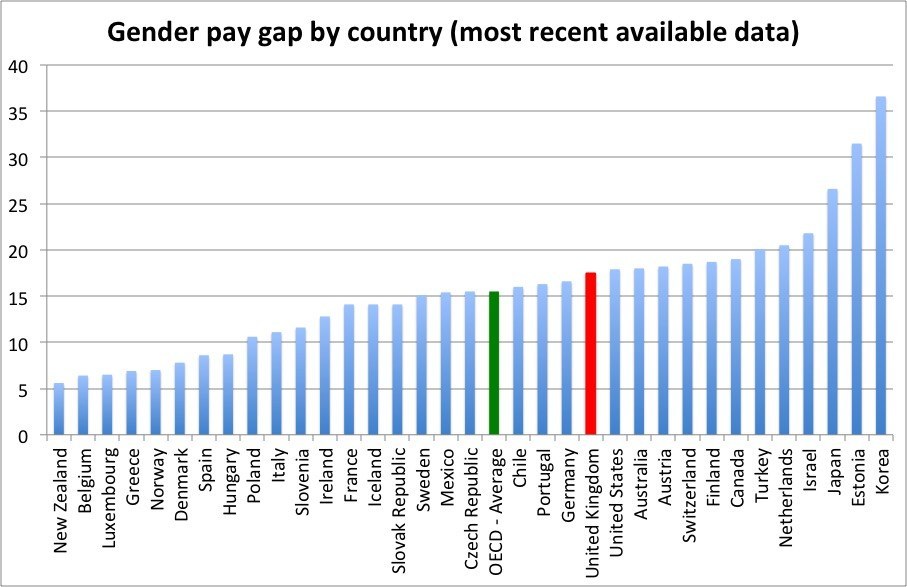

There are gender pay gaps in seemingly every country. But we're not exactly leading the world in gender pay equality.

That's us in red. The OECD average is in green. We're subpar among our international peers. We're also improving more slowly than the average.

There are ways of improving the situation. One is subsidised childcare.

The Equality and Human Rights Commission report found that helping to pay childcare costs gets women working and reduces the pay gap. Extended maternity leave, it says, helps get women working but can exacerbate the differences in pay.

Wollaston says: "Childbirth is part of it, but there's also a pay gap for women who don't have children, so it's not the whole story." Childbirth's impact on the pay gap can be reduced by things like shared parental leave: "We need more flexible working, to make flexibility the norm for everyone, men as well as women."

Encouraging women into traditionally male-dominated areas is important.

"We have to make girls realise the advantages of things like STEM qualifications," says Wollaston. "Especially technology, which is such a growth industry and often highly paid. One solution is to close the gap in these choices, to make it normal for women to work in technology. The gap is actually growing in technology, and the economy is losing out, because we're losing talent to other countries like the US. This isn't a short-term fix."

There are lots of obstacles. "Families and teachers often warn women that they'll be the only woman there if they choose a male-dominated industry, and they might not see a realistic path to the top," Wollaston says. "And stories of bullying and harassment can put women off some industries, notably technology."

According to a European Commission report, increasing the minimum wage also helps reduce the gap.

"Women are also the major beneficiaries of minimum wages so any advances in minimum wages level help women disproportionately," it says, pointing out that after the British minimum wage was introduced in 1998, the wage gap dropped by five percentage points within eight years.

An increase in the minimum wage was announced by chancellor George Osborne last week.

And, yes, improving transparency is important too. So Cameron's initiative might well help.

The European Commission report says that when employees are kept in the dark about each other's pay, gender pay gaps worsen, and that forcing companies to be open about pay can help improve the situation. Denmark and Sweden are among countries that do this already.

"Transparency can help [combat discrimination] by showing women what their male peers are earning and encouraging them to seek the same," says Wollaston. Her organisation identifies 10 steps for business leaders to take to promote women in STEM roles.

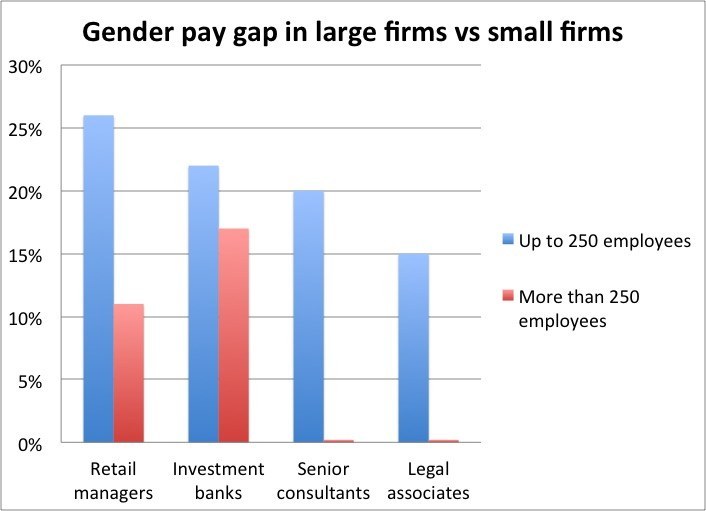

But Cameron may be focusing on the wrong companies.

Data from salary comparison website Emolument suggest that in at least four industries, large companies tend to have smaller wage gaps than their smaller rivals. It's not clear whether that pattern holds across all sectors, but if it does, applying the transparency law only to companies above 250 employees may limit its effectiveness.

As well as transparency, the government has taken other steps towards ending the pay gap. It has pledged to double the amount of free childcare parents can claim, from 15 hours a week to 30 hours a week.

And its minimum wage increases, as discussed, are expected to help women more than men – has said that a Treasury analysis suggests that 65% of "winners" from the new National Living Wage proposals will be women.

The government also claims that 20.6 million people are now able to take advantage of flexible working practices, although it is not clear where that figure comes from, or whether, if it's accurate, it is actually the result of government intervention.

The previous government also introduced shared parental leave, allowing fathers to split up to a year off work with mothers.

Cameron said these steps are going to end the gender gap "within a generation".

It's an achievable task: On the current trajectory, the gap is on course to end by the mid-2050s. Cameron is suggesting the process will be sped up by about a decade.