An influential group of MPs has called for a tax on sugary drinks.

It follows the (controversially delayed) publication of a report by Public Health England that finds sugar taxes significantly reduce the amount of sugary foods people buy.

The report says that Norway, Finland, Hungary, France, and Mexico have all seen the consumption of sugar go down since they introduced a sugar tax. After a 10% tax was levied in Mexico, it says, average consumption went down 6% – and 9% among people on the lowest incomes.

Earlier studies have found even more dramatic results. A 2013 meta-analysis, or study of studies, published in the journal BMC Public Health found that on average, every 1% rise in sugar taxes leads to a 1.3% drop in sugar consumption.

The findings of the meta-analysis and the Public Health England report suggest sugar taxes would be more effective than, say, alcohol taxes.

A UK government report last year found that a 1% increase in alcohol price leads to a 0.6% drop in beer consumption or a 0.86% drop in wine consumption. (That's an average of all the studies they looked at.) Tobacco is similar: A Warwick University study found that a 1% rise in cigarette prices leads to somewhere between a 0.5% and 0.7% drop in consumption.

Alcohol is already heavily taxed in Britain: 18p a litre for beer, and £2.73 a litre for wine. Cigarettes are taxed at 16.5% of retail price. (These taxes are over and above the usual 20% VAT.)

The next question is whether sugar taxes reduce obesity, not just sugar consumption. That's harder to measure.

After all, consumers could simply switch to other, equally fattening products. However, one Finnish study found a solid link, and suggests that sugar taxes can reduce obesity-related health issues such as heart disease and obesity.

The Public Health England report quoted above agrees. It says that if sugary drink consumption is reduced in five years' time until it's only 5% of Britain's total energy intake, it will prevent more than 77,000 avoidable deaths in the next 25 years.

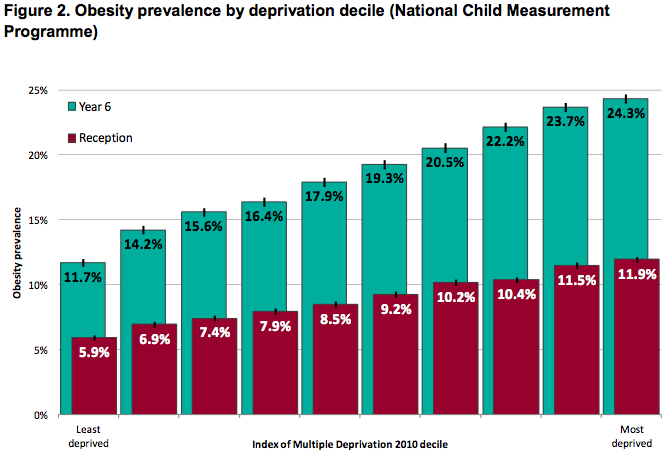

Critics of a sugar tax suggest that it is a "regressive" tax – that is, it hits the poor harder than it hits the rich.

That's certainly true, in one sense. Poor people would spend a greater proportion of their income on this tax than would rich people.

That's true both because a single drink represents a larger fraction of a poor person's income than it does a rich person's, and because poor people tend to buy more soft drinks than rich people do.

However, advocates for the tax argue that poorest in society would also benefit the most from a sugar tax.