ZAGREB, Croatia — Ahmed sat on the side of the road with two friends outside a refugee camp in the neighbourhood of Zaprude, Zagreb. The shelter itself was bleak: a large industrial block, guarded by police, with mattresses strewn across the floor.

Nineteen years ago, the same space sheltered displaced Croatians returning from Germany and other European countries after being uprooted during the Bosnian war. Today, it is a roof over the heads of refugees fleeing war in Syria, making their way to western Europe. Ahmed, like many others in the Croatian capital that day, was waiting for a ride to the border, where small towns are host to hundreds of refugees attempting to pass through into Slovenia.

"I'm going to Germany," he said as he slung his bag into a taxi. "I have a brother there. He's waiting for me."

The word "Germany" is uttered by the majority of refugees fleeing poverty and war with the hope of starting a new life in western Europe. For those crossing the Croatia-Slovenia border, eyes lit up at the very mention of the country.

Where were they heading to?

"Germany."

Where did they think they'd be most welcomed?

"Germany."

Did they have family in west Europe already, and if so, where?

"Germany."

Germany is their final destination, the light at the end of a long, arduous journey that has taken them across rough waters, open fields, and at least six international borders. As European governments continue to tighten the seal of their borders and push refugees back and forth to neighbouring countries, Germany has been hailed as "heroic" for welcoming the majority of the asylum-seekers that have arrived in the EU so far this year with open arms.

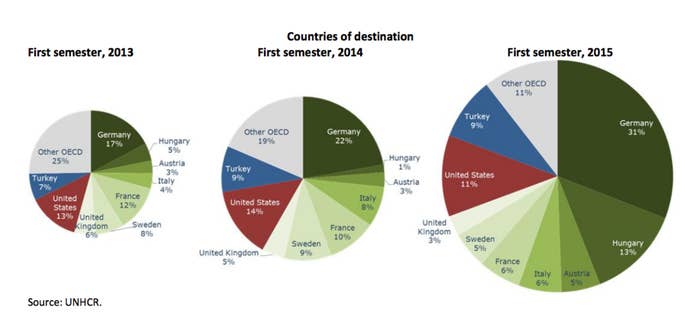

The country's efforts didn't go unnoticed – or without influence, either. The UK, buckling under international pressure, agreed to take in 20,000 asylum seekers over the next five years. Meanwhile, Angela Merkel promised that her country would take 800,000 asylum seekers this year, with numbers expected to rise. Over the last three years, Germany has been the top destination for asylum-seekers – in the first three months of this year, nearly a third of all people seeking asylum were heading there.

So what is driving this surge? Of course, the allure of citizenship is a clear incentive for refugees seeking a safe haven in Europe. But while Germany's generous response has lured many refugees to the country, another reason for the large influx could be explained by something closer to home: family.

Syrian communities existed in Germany long before the unrest in Syria escalated into a brutal civil war. In 2011, there were more than 30,000 Syrians registered in Germany, but as that number does not include those who were naturalized, the true figure is thought to be higher. Although the motivation for refugees to head to Germany will still vary greatly from person to person, loose family ties – including distant relatives or extended family – in the country have been one of the many driving forces for refugees hoping to forge new lives there.

"Germany isn't a go-to place only because it's relatively easy and welcoming, but because many of the refugees already have families or connections in the region," Wenzel Michalski, the Germany director for Human Rights Watch, told BuzzFeed News. "Then, of course, there's also a number of refugees, typically men, carrying over their brothers and sisters, parents, and children over to the country, setting up lives for their families here, too."

Where refugees have built stronger set-ups in the country, a chain-like movement – in which people pull family members across Europe one by one, or in groups – has been happening, easing the arrival for some refugees. Michalski said the "networks" used to rekindle family relations were growing, and that with every new Syrian arrival in Germany, there will be a new opportunity for another connection. He spoke of a young Syrian teenager he met at a train station in Munich, whom he brought to his apartment so he could contact a family member who lived in the area.

"He had a distant cousin here in the city, one he hadn't spoken to in a long time," Michalski said. "They knew each other through a network of family ties and friends. So he rang him up and he came to the apartment. When he arrived, there was a lot of joy. When we spoke to his cousin, he said this was the 20th cousin he'd welcomed to the city since he arrived five months ago."

But for refugees who don't have existing family ties in Germany, they are left to create their own set-up.

Before Mohammad was forced to flee Damascus, Syria, he was an English teacher for five years. He decided to head to Germany, the country he deemed the safest and where he hoped he would be able to continue working in education. He now lives in an apartment with refugees from Syria, Afghanistan, and Iraq, in a small town in eastern Germany which he asked BuzzFeed News to not name. He said that he and many of the other refugees he lives with left some – or all – of their family at home so they could prepare a base for them in Germany, with the intention to gain citizenship before bringing their relatives over.

Many refugee women and children may now be making that journey. In the last month, the numbers of women and children recorded crossing European borders has spiked. Unicef reported a sharp rise in those traveling across Greece and Macedonia, and in the past week alone, they say, the "numbers are climbing" in current hotspots like Croatia. They expect the actual number of women and children reaching reception centres in Europe is likely to be double the reported figure, as many families travel onwards without being officially registered.

Long waits for citizenship have forced some refugees to wait longer to be reunited with their families. By July of this year, there were 324,940 asylum applications pending for Germany, with two thirds of them made by men.

Mohammad and others he lived with were told they'd have citizenship swiftly, some within one month – but after 11 months, he still faces an uphill battle to gain citizenship, and hasn't seen his family since he left.

"When we get citizenship, we can get jobs and use the money to bring our families here," Mohammad said. With money, he said, they can afford to fly their wives and children to Germany and avoid the treacherous route taken on foot by the majority of refugees. Mohammad's story was not uncommon: He lived with a man from Damascus, who wished to remain anonymous, who was arrested by Assad's regime for writing satire in his local newspaper. His wife and children wait at home, hoping his asylum application will be accepted soon so they can be reunited.

"I worry about them every day," he said. "I can't sleep. I miss them. Every day I am thinking 'When can she come? When can my children come?'"

For the refugees making their way across Europe as winter approaches, facing harsher weather conditions and heightened border security along the way, it is unclear if Germany will remain the ideal destination. While some received a jubilant welcome at train stations and towns in the country, for others, the response has been more hostile. Despite their desperate efforts to bring their families across Europe to Germany, many are now finding that the dream of the tolerant and safe country they longed for does not necessarily align with the reality.

In the town Mohammad resides in, tensions with the local community were growing – he said they hadn't accepted the refugees' arrival, hurling racist abuse at them when they went to the market. Officials in Germany have also cited concern over a rise in racist assaults and violent incidents, as well as the growth of far-right networks following an increase in the number of arson attacks on asylum centres and hostels.

When Mohammad and those he lived with heard that refugee camps had been burned down elsewhere in the country, they became increasingly concerned for their safety.

"When I came to Germany, I needed to come here," Mohammad said. "But now, Germany isn't good. I needed to find us somewhere safe, and to complete my dream. But when I came here, my dream has been destroyed. We are wondering if people [will] come to us in the middle of the night to hurt us. No one can protect us here."

Many refugees are still left with a conflicting feeling of mourning for their old home while longing for a new one. Mohammad and many others in his refugee community said they were now considering moving to England, where they believe they have a better chance of gaining citizenship and leading a normal life with their families.

"I wish it didn't happen to Syria," Mohammad said. "I miss my life. Why did this have to happen to my country?"