We open on a girl’s face. She stares back at us as she begins to sing — her vocal power gorgeous and staggering. The camera spins around, eventually revealing the young people assembled around her in the woods, of various ages and ethnicities, who join together to form the chorus of “How Shall I See You Through My Tears?” from the obscure 1983 musical The Gospel at Colonus.

While the show might not be familiar to all but the most diehard theater fans, the song has become indelibly linked to the 2003 film Camp, and to Sasha Allen’s stirring rendition.

It’s the first thing viewers of the cult classic musical about kids at theater camp hear, setting the stage for so much of what’s to come: the campers’ raw talent on display, the isolation they experience in their troubled home lives, and the way the fictional Camp Ovation — based on the famous Stagedoor Manor, where the movie was filmed — offers a respite for these outcasts.

It’s the perfect opening, and it’s thematically essential to what follows. But it almost didn’t happen.

“We had no contingencies. We had very little money,” Camp writer-director Todd Graff told BuzzFeed News. The sequence was going to take place outdoors on one of the last nights of filming in September 2002. “Then it started to rain, and I mean like biblical, torrential, piss-down rain.”

The cast retreated to a giant tent, and in order to will the rain away, they huddled together and sang spirituals. “Bless their hearts, they really believed they could make it stop raining if they prayed hard enough and sang loud enough,” Graff said. “And boy, they tried. But it just didn’t happen.”

As night became morning, Graff was forced to face the reality that he was most likely going to have to cut “How Shall I See You Through My Tears?” from the finished film. Then, an idea struck him: If they added a last night on top of the last day of shooting, they could try again. It would mean working 24 hours straight for most of the cast and crew, but miraculously enough, everyone agreed.

“It’s freezing cold and it’s 5 o’clock in the morning and they’re wearing sleeveless whatever, and I’m having them suck ice cubes so that you can’t see their breath when they’re singing,” Graff said. “They’re like hypothermic doing this thing, but they were really doing it for Sasha. They just couldn’t imagine her number not being in the movie. It was after the sun had come up, and everybody just stepped up. And we got it. It was the very last thing we shot.”

It’s a scene that underlines the film’s themes, and its dramatic behind-the-scenes story captures the camaraderie and tight-knit community spirit that made Camp such a success among the people it was made for: the misfits, the losers, the theater geeks.

“Theater people!” Graff exclaimed, reminiscing about the way “How Shall I See You Through My Tears?” came together. “We take care of our own.”

Camp is the kind of movie you’ve either never heard of or can quote verbatim. If you fall into the latter category, there’s a good chance you saw it in theaters back in the summer of 2003. Most likely you were a teenager, or at least close enough to being a teenager to still remember what it felt like to be a high school misfit, loser, and/or theater geek.

Because this was never a movie for the popular kids; it was crafted especially for that latter group — a particularly awkward and, at the time, underrepresented subset of high school outcasts. Camp is about how your love of show tunes could be an asset instead of a mark against you. If you loved the movie, you were different, and chances are, what appealed to you about it was the way it encouraged you to embrace that weirdness, not to run from it.

At the film’s center are Ellen (Joanna Chilcoat), a lovelorn loser forced to take her own brother to the prom, and Michael (Robin de Jesús), a sometimes drag queen beaten up by his fellow students and disowned by his parents over his sexuality. Over the course of the summer, Ellen and Michael fall for the charms of supposed straight boy Vlad (Daniel Letterle), who has no problem commanding the attention he so desperately craves.

The campers — who were played by unknown actors chosen more for their ability to belt than for how they looked shirtless — are united by their passion for theater and their inability to fit in with the so-called normal kids they spend most of the year with. For these teenagers, Camp Ovation represents a sort of Mecca: It’s the place they go once a year to escape society’s restrictive limitations. Here, they can be as loud and as queer as they want to be, free from the shame that would otherwise silence them.

It’s a pleasant fantasy, and one that Camp’s target audience — the same kinds of outcasts depicted in the film — could not resist. It offered a home away from home where talent was prized above looks, nerdy knowledge was an asset, and heterosexuals were the minority.

And somewhere out there, Camp Ovation was real.

Graff based his script for Camp on Stagedoor Manor, which he attended first as a camper and later as a counselor and musical director. But a lot had changed since he started going in 1975.

“It was a very different kind of place than it is today. Today, it’s still insane, but it’s insane within a kind of structure,” he said. “You don’t fear for the lives of the children. You get the feeling that they actually sleep at night and they get fed meals and whatever, even though they’re rehearsing a million hours a day and it’s craziness.”

Stagedoor Manor did have its issues in the ’70s — Graff remembered a scabies outbreak one year and another when the camp decided to remedy its negligent fire safety measures by having the scene shop build fire escapes…out of wood. “Child services came and they said, ‘You can’t have 150 kids here with wooden fire escapes,’” Graff recalled. “They shut it down.”

But generally, the Stagedoor Manor that Graff remembered is a lot closer to Camp’s Camp Ovation. (And ownership has also since shifted.) The aspects of Stagedoor that most directly inspired the movie — the crazy production schedule and the passion of the campers — lingered with Graff for decades as he searched for a creative outlet through which to filter his experiences.

“I always felt that there was a story in it. I didn’t know if it was a stage musical or a movie or what,” he said. “I went off and had my acting career and my writing career, and then decided I wanted to direct because I was unhappy with the way the movies I was writing were turning out when they were handed to other directors. So I had to figure out what movie that would be for someone to allow me to direct.”

The answer was Camp.

What Graff had written was so specific to musical theater as a whole and to his experiences in particular that it wouldn’t make sense to hand it off to another director. He first wrote the screenplay on spec and staged it as a workshop, as if Camp were a stage musical.

But as Graff began to look for funding to make his workshop a film in earnest, he realized he was fighting an uphill battle.

As Graff struggled to find producers, he realized the specificity that made Camp perfect for his directorial debut would be a challenge, as would the film’s subject matter, which was more controversial than he’d intended.

Camp’s queerness is as relentless as it is glorious. This is a movie in which campers of all ages don drag to cheer up their morose friend, in which a gay boy seduces and has sex with his female friend just to prove he can, and in which the objectification of the sole straight guy is presented as the unavoidable consequence of perfect abs.

“Back then, there was no way you were gonna have two boys — one naked, manipulating the other, who’s a drag queen, who gets queer-bashed in the first scene — and they’re about to kiss,” Graff said, referring to the film’s final moments, in which Vlad suggestively confesses his sexual confusion to Michael, whether out of genuine interest or just to get him worked up. “It just was not gonna happen.”

At one point, Graff brought his script to Paramount, where he was asked if he could transform the outcasts of Camp Ovation from queer kids to Trekkies. (There was, after all, cross-promotion at stake for Paramount, which owns Star Trek.)

“They said, ‘Well, you know kids at that age who are very into Star Trek often have a very tough time. They get picked on, they get bullied,’” Graff recalled. “I said, ‘Do you really equate being a Star Trek fan with being a 15-year-old queer-bashed drag queen?’”

He refused to give in. Of course, that meant he had to search even harder for the support necessary to make his film.

“It was clear pretty early on it was not gonna get made [by a major studio]. And so I sold my house and moved to New York,” he said. “I did nothing but try to make this movie for four years, in the way it was written.”

Eventually, he got funding from Killer Films and IFC Films (Camp producer Michael Shamberg is now an adviser to BuzzFeed Motion Pictures), but there were still hurdles to overcome.

Casting, in particular, was not going to be easy.

Graff was looking for raw talent — young people who looked, felt, and acted like the characters he had written. One of the first kids cast was Anna Kendrick: Along with Sasha Allen, she was the only actor to make the transition from Graff’s workshop productions of Camp to the final film. At the time, Kendrick had never made a movie, but she had already made her mark on Broadway in the show High Society, which starred Graff’s cousin, Randy.

“To me, Anna was ‘Anna Banana,’ Randy’s little friend from her show, for years,” he said. “When we shot Camp, she was 16, so I’d known her for several years before we ever made the movie, and I just always knew this kid was amazing. She was a very precocious kid, but she was cool. She was not obnoxious. She was a kid you liked hanging out with.”

Kendrick’s Fritzi — an ambitious and possibly homicidal young camper — was a scene-stealer, but Camp largely came down to the relationships between Michael, Vlad, and Ellen.

Graff held auditions at Stagedoor Manor, among other places, and he also enlisted the help of Broadway casting director Bernie Telsey, who — because he’d helped cast Hairspray and Rent — had a database of talented young performers to choose from.

“They would go all over the country looking for people for all of the companies of those shows,” Graff said. “And they would always have kids who were too young, and so all those kids we could draw from. Having said that, it was a long process. It was a real thing. It was Bernie putting up flyers at schools. … We saw a ton of kids in order to finally end up with the ones that we got.”

Graff also went to a former college classmate who had become a dance teacher. Among the teacher’s students was Chilcoat’s younger sister, and when the teacher asked if Graff needed singers too, she was at the top of the list. At that point, Chilcoat was still living in Baltimore, where she had been performing in dinner theater from the age of 9. And she was immediately drawn to the character breakdown for Ellen.

“The character description [was], ‘Ellen is undergoing an unfortunate adolescent collision of smart mind, loud voice, and chunky body,’” Chilcoat recalled. “And I remember being like, I’m not that chunky, but yeah, that’s pretty much me.”

For Michael, Graff cast Robin de Jesús, who had heard about an open call through a teacher at his school and arrived to audition with, as Graff remembers it, “a zillion others.” De Jesús grew up poor in the projects of Connecticut and had never been to a Broadway show. His only experience with musical theater had been listening to original cast albums he checked out from the library, and that innocence added to the authenticity that Graff was looking for.

Also authentic: de Jesús’s less-than-perfect skin, which ended up being one of Michael’s character traits. “He came in looking like that,” Graff said. “I have to say that if he had insisted on covering his zits, I would have let him rather than expose him that way, but he was the one who from the beginning said, ‘I think this is Michael.’” (De Jesús did not respond to BuzzFeed News’ request for an interview.)

The part of Vlad had been cast, but Graff ultimately deemed Daniel Letterle a better fit for the role when a theater agent submitted him after he got back from doing West Side Story in Germany. As with Chilcoat, Letterle was distinctly drawn to the character’s connection to his own real-life experiences.

“The whole reason I think I wanted to be an actor is because I wanted to be liked. I totally identified with that. It wasn’t a stretch,” Letterle told BuzzFeed News in an interview over Skype. “You’re around theater people all the time and you’re always sort of competing for attention and always trying to be cute and funny and hip and everything. And that’s what Vlad was.”

The rest of the cast included Alana Allen as mean girl Jill, Vince Rimoldi and Steven Cutts as gay campers Spitzer and Shaun (respectively), Tiffany Taylor as jaw-wired-shut Jenna, and musician and music producer Don Dixon as alcoholic composer Bert Hanley. DeQuina Moore, who went on to join the original Broadway cast of Legally Blonde and the 2003 revival of Little Shop of Horrors, had a smaller role as a camper also named DeQuina.

Cutts was the last person to join the cast. He was called in to audition at Graff’s home, where the rest of the cast was gathered for a rehearsal. “[Graff] was like, ‘Do you feel comfortable doing this in front of everybody?’ I was like, ‘Yeah, kind of,’” Cutts recalled to BuzzFeed News in an interview over Skype. “He had everybody turn around.”

Once the entire cast had been assembled, they bonded quickly. During the rehearsal period, the teenagers lived near each other and explored New York City together while learning their parts. “Nobody can really understand the kind of family that grew up around that film,” said Chilcoat, who was, at 16, one of the youngest actors in the film. “It was such a unique experience.”

But even with funding and casting set, there were still more challenges ahead for Graff, like getting the rights to all the music he wanted to use before filming began.

He described his music choices as “very my taste and my experiences.” He chose “Turkey Lurkey Time” because his cousin had appeared in Promises, Promises, which he had seen countless times at a young age.

And he chose “I’m Still Here” — plus the snippet of “Losing My Mind” the kids sing on the bus to camp — because Stagedoor Manor had put on a production of Follies while he was working there. “That always seemed like a pretty good example of just how insane the show choices can be at this camp,” Graff said. “We really did that. We really had a 14-year-old with braces singing ‘I’m Still Here.’”

“Wild Horses,” the song Vlad auditions for Camp Ovation with, was chosen simply because it was popular when Graff attended Stagedoor, but it wasn’t his first choice. Graff had written the Allman Brothers song “Sweet Melissa” into the script, based on the real audition of the actor playing Jesus in a production of Jesus Christ Superstar that Graff directed in college. But the Allman Brothers refused to license the song to an indie film, especially one with a budget of, as Graff put it, “like $11.”

Camp’s music supervisor, Linda Cohen, suggested Graff go with his second choice — which she was horrified to learn was a Rolling Stones song. “She said, ‘There’s just no way. They’re not a charitable organization, the Stones,’” Graff remembered. “But she gave it a shot and it went all the way to Mick Jagger reading the script, and I think they charged us $250 or something crazy for ‘Wild Horses.’ It was like, ‘Fuck you, Allman Brothers.’”

Aside from Mick Jagger, Camp’s other major savior was Stephen Sondheim, who came on board early after sending letters back and forth with Graff and reading the script. He gave Graff permission to use his entire oeuvre, and his involvement proved essential to getting other composers to grant permission for their music at prices the production could afford.

“When it has the Sondheim imprimatur, it’s really the gold standard. Everybody else lined up behind him,” Graff said. “Even though it looks like we need an $8 million music licensing budget, in fact we’ve gotten all these songs for under $100,000 total.”

With the music rights in order, filming on Camp could finally begin. The actors relocated to the real Stagedoor Manor in Loch Sheldrake, New York, where they moved into actual bunks, allowing for an authentic camp experience. “We would have campfires at night and sing-alongs,” Letterle said.

Chilcoat remembered sleepovers and “mischief,” noting that all the adults stayed at the edge of camp, giving the young actors some degree of freedom. (Child services were also on the premises, Graff was quick to note.)

“It was like we were teleported back to camp days for real,” Cutts said. “There were specific cliques. Certain people had parties and you’d stumble in, like, ‘Oh, you guys are getting together?’ It was something.”

Essentially, it was just kids being kids. Or, at least, theater kids being theater kids.

“It was a lot of fun," Letterle said. "It was exhausting, though, too."

The entire film, including nine full musical numbers, was shot over 18 days. Those days were tightly packed, and the musical numbers — see “How Shall I See You Through My Tears?” — were particularly challenging.

In one of the film’s most memorable sequences, campers simultaneously perform Follies and Promises, Promises: The action shifts between Lisa (Julie Kleiner) belting “I’m Still Here” and Jill leading the ensemble in a show-stopping performance of “Turkey Lurkey Time.”

The scene required Kleiner to do double duty, simply because Graff did not have enough actors to fill out the Promises, Promises ensemble without her. So although she’s very clearly performing “I’m Still Here,” she’s also singing “Turkey Lurkey Time” — in a blonde wig.

“And I literally have close-ups of her,” Graff said, laughing. “I go from a close-up of her doing ‘I’m Still Here’ across camp to a close-up of her in ‘Turkey Lurkey.’”

The other challenge with that particular scene: Patrick Cubbedge — who played Patrick, one of the younger campers — got sick and began vomiting mid-performance, not unlike a scene in Camp in which Jill throws up repeatedly while singing “The Ladies Who Lunch.” Cubbedge, who had woken up at 3 a.m. to do the scene, refused to quit, just like Jill, who continues singing until Fritzi, who has poisoned her, takes over.

“He got up there and he danced his heart out,” Graff said of Cubbedge. He wanted to send the young actor back to bed, but Cubbedge refused. “He would do a take, he would go outside, he would throw up, they’d give him a bunch of water, he would come in, he would do a take, he would go outside, he would vomit.”

But perhaps Graff’s biggest feat was getting Sondheim to appear as himself, something Graff had written into the script that the iconic composer initially refused to take part in. But when Graff explained to Sondheim that if he wouldn’t do it himself, he would have to find a lookalike or pick another composer at Sondheim’s level (of which there are none), Sondheim said yes at the very last minute.

And once he was on set, Sonheim refused any special treatment, even staying in one of the Stagedoor bunks instead of at a hotel. Yes, it was just like real camp, “except that Stephen Sondheim shows up one day, and you’re like, What?” Chilcoat remembered.

“It was really, really remarkable that he did that for somebody. He didn’t owe me anything — it’s not like I had starred in four of his musicals and I asked for a favor,” Graff said. “I was just this guy saying, ‘Nobody ever makes movies for kids who are into musical theater, ever. Even Fame is not that.’ And he said OK.”

Sondheim is humble, to say the least, about his involvement with Camp. He told BuzzFeed News he was motivated not only by Graff’s sincere pleas, but by the appeal of playwright Arthur Laurents, a friend and supporter of Graff’s. “I had a good time on the shoot, and thought (and think) I was terrible in the movie,” Sondheim wrote in an email. “But I don’t regret it.”

Though he was able to keep the Sondheim scene intact, Graff did continue to modify his script as filming went on. And one of the most contentious discussions was over the relationship between Vlad and Michael, and just how far that final scene between them should go. After all, Graff wanted to make sure Camp earned a PG-13 rating to make it accessible to the very teens it was about.

Vlad presents as most likely straight, and Graff based that character in part on himself: a repressed gay teenager whose opposite-sex bed-hopping behavior reflects his underlying sexual confusion. “I’m gay, but I can’t be gay yet, so I’ll manipulate every girl around, because the girls at the camp are girls that generally speaking don’t ever get dates 10 months a year, so here, if any boy pays attention to them, they’re very easy,” Graff said of Vlad’s mindset. “It was that thing of working through your own sexuality by manipulating people around you."

And so when Vlad, naked and dripping wet from the lake, tells Michael that he’s not sure what he wants, he might actually be sincere, which raised an interesting question: Would these two boys actually consummate their muddled relationship?

“We were sort of navigating how far to push the last scene. It’s like, Should there be a kiss? Should there not? Should he push his head down? Should he not?” Graff recalled. “Thirteen years ago, there was just no way you were gonna be able to have two underage boys make out and not become a thing.”

It was also something that Letterle struggled with. “One of the ideas came up that Michael and Vlad have a sexual encounter. It freaked me out at the time, so I said no,” he remembered. “But I think that would have been fine if that would have happened. It would have made sense. I don’t know. I wasn’t ready yet.”

Graff hoped that the changes he made would ultimately broaden Camp’s audience, without sacrificing the authenticity that would endear it to the outcasts who never saw themselves depicted onscreen.

But in terms of box office numbers, they didn’t help.

The domestic gross for Camp was just $1.6 million, although it went on to make $2.7 million worldwide.

And reviews were mixed. Rolling Stone’s Peter Travers called Camp “the modestly perfect antidote to a synthetic, overblown movie summer: a blast of exuberant fun that stays rooted in humanity,” while Michael Wilmington at the Chicago Tribune said it was “shallow, forced and phony — in some of the same ways that Fame was a phony picture of the New York High School for Performing Arts. And this film doesn’t have the compensating gloss, energy and excitement of Fame.”

“There were some really out-and-out raves, like from Rolling Stone or [Ty Burr at the Boston Globe] — like serious real critics who gave it true money-quote kind of reviews,” Graff said. “And then there were critics that absolutely hated it. They didn’t know what to make of this thing. They just didn’t get it.”

But the response from the theater community was nearly uniformly positive, which is what Graff had hoped for all along. He always knew the audience would be somewhat limited, so he was more fixated on authenticity: Camp needed to work for the people it was about.

And if its cult status among young people is any indication, it did achieve what the filmmaker set out to do. All of the actors described enthusiastic encounters with fans, a phenomenon that has only increased over the years.

“It’s absolutely incredible,” Chilcoat said of getting recognized for the film. “I can’t believe it’s been 12 years and people are still talking about it, this tiny little movie.”

Graff remembered getting letters from those who were touched and inspired by the film — the outcasts that he had made a point of showcasing found comfort in its honest depiction of diverse sexuality and gender expression.

“It was a formative film for a bunch of people. I’m very proud that it found its way to those people,” Graff said. “For a bunch of kids who really felt like, I’m just some kid somewhere, and I had no idea that a place like this exists, or other kids like this existed like me, that were cross-dressing, or liked other boys, or were into musical theater — all those kinds of things…there was just not a lot out there for them.”

But for most of the performers looking for their big breaks, thrilled by the chance to finally showcase their talent, Camp wasn’t quite the star-making turn they’d anticipated.

Letterle in particular had a rough go of things after Camp’s release. Despite the fact that he was the film’s lead, showing off both his theater training and his well-placed muscles, he starred in one other movie, 2005’s gay indie comedy The Unfabulous Social Life of Ethan Green, before fading into obscurity.

“I thought I was going to the moon, man,” Letterle said. “I thought that was it. I made it. It’s easy street from here on out. Boy, was I wrong.”

Letterle returned to his home state of Ohio in 2006, a year after Ethan Green’s release, and has stayed out of the public eye since. When BuzzFeed News first asked Graff if he knew how to contact his former star, Graff said it had been years since he’d heard from him.

But Letterle’s seeming disappearance had nothing to do with Camp and everything to do with his personal demons. “I’m still off the radar. Look, I have bipolar disorder and I was a drug addict, basically,” he confided. “I struggled for probably about seven or eight years.”

Letterle is refreshingly honest about his life after Camp, and the way his Hollywood dreams didn’t pan out as expected. His story is one of the harsh realities of fame: Sometimes talent isn’t enough. Survival for a working actor isn’t just about getting people to know your name, and Camp’s burgeoning cult in the years following its release did little to help Letterle.

“I was homeless for a while, but I had a Facebook account,” he said, noting that he lived out of his car in L.A. for a year after finishing Camp. “I would go to the library, mainly to sit in the air conditioning, and I’d talk to my fans, and it was just this surreal experience. Like, I have fans. I’m homeless, but I have fans. At that point in my life, it felt like, I should use these fans and try to build something up, but nobody wanted to talk to me. I was a lousy piece of shit at the time.”

And yet Letterle is far from bitter. He’s now happily married to his wife, Danielle, and working at a restaurant, far removed from his brief stint as a leading man. But he looks back fondly on his experience with Camp.

“I have nothing but good things to say about it. It was a great experience, and all the people I met were wonderful. … Those are some of my fondest memories, no doubt,” said Letterle, who recently reached out to Graff in advance of a trip to New York. “I always wanted to be the star of a movie, and I was. Maybe I didn’t live that life, but I set out to do it and I did it, and it was one of my greatest accomplishments. I think what I learned is that anything is possible if you really give your whole self to it.”

Camp’s most mainstream success story is Kendrick, who broke through in 2009 with her role in Up in the Air, for which she was nominated for an Oscar. Since then, she’s gone on to big-budget franchises (the Twilight and Pitch Perfect series), modern movie musicals (Into the Woods and The Last Five Years), and acclaimed indies (Drinking Buddies and Happy Christmas).

But while Kendrick — who was unavailable to be interviewed for this story — might be the most well-known former Camp star, she’s not the only actor to have continued working. Her co-stars, however, have mostly made their marks in theater.

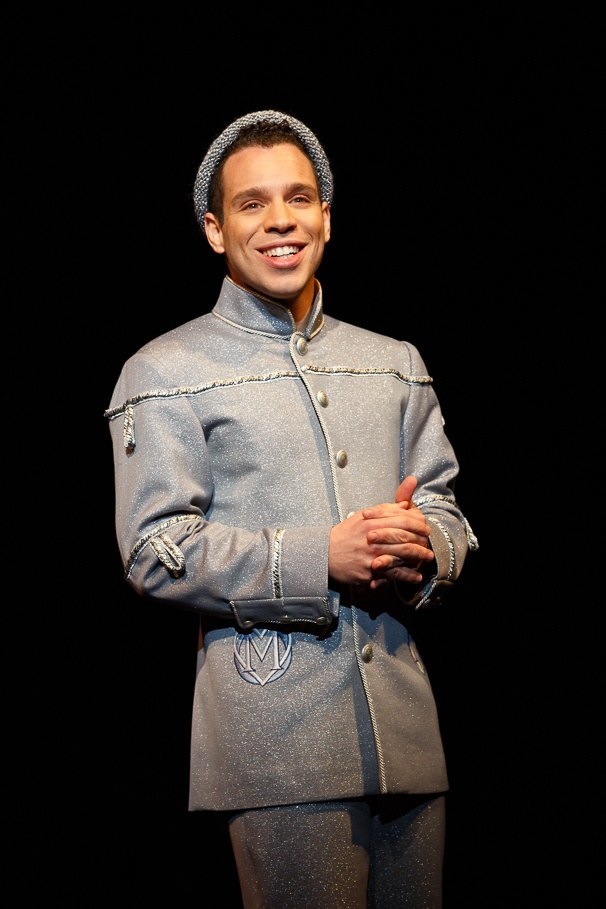

De Jesús earned Tony nominations for Lin-Manuel Miranda’s In the Heights and for the 2010 revival of La Cage aux Folles. Currently, he’s playing Boq in Wicked on Broadway.

Sasha Allen toured as the Leading Player in Pippin and was in the 2009 Broadway revival of Hair. (If you listen to the cast album, she’s the soloist on “Aquarius.”) She gained more recognition when she appeared on the fourth season of The Voice.

“To be in high school and to do this workshop, and then to be in college and to do the movie, it was really the beginning of me figuring myself out, me starting a career, me learning the rules of being a working actor,” Allen told BuzzFeed News in a phone interview. “Todd really gave me my real start.”

It also was the start to a deep friendship between Allen and Cutts, who said the two are “basically married.”

Before he got the gig in Camp, Cutts was still nursing his wounds after being replaced when Hairspray moved to Broadway. (He had left school to appear in the original workshop as Seaweed J. Stubbs.) During filming, he caught the attention of Camp choreographer Jerry Mitchell, who was also the choreographer for Hairspray.

“After working with him on Camp, he invited me to audition for Hairspray. I ended up doing three or four companies of Hairspray,” Cutts said. “It picked me up right at the perfect time when I was down and I was really questioning whether I had what it took to do this.”

Chilcoat tried to continue acting after Camp, retaining an agent and going on several auditions. But she didn’t want to move to New York, and while she was working as a long-term high school substitute teacher and working on her master's in education, she discovered acting wasn’t her priority.

“[My agent] was like, ‘Look, you either need to commit to this 110% or you need to back out,’ basically,” she recalled. “And I was like, you know what? I’ve got to finish school. I’ve got to keep my job.”

But there’s still a bit of Camp in Chilcoat: She now teaches film, theater, and television production, which means she gets “all the nice, wonderful, weird, smelly kids” — the same outcasts that she numbered herself among when she auditioned for the movie more than a decade ago.

“As a kid, I was never good at sports. I was never really good at socializing or talking to people or making friends. I was good at theater,” she said. “And theater gave me a family, and theater gave me a community. And I knew that when I grew up, I needed to do something to spread that.”

Chilcoat doesn’t tell her students that she was once the star of a movie musical, but they inevitably figure it out, especially now in the age of Google. “My favorite is when a kid comes running up to me and goes, ‘Ms. Chilcoat, did you know you were in a movie?’ And I’m like, ‘What? I was? That’s crazy,’” she said, laughing.

And sometimes, she does watch Camp with the students in her film class, providing them with behind-the-scenes context. They’re fascinated by Chilcoat’s unique perspective — and appropriately amused by seeing her make out with Letterle. But watching herself onscreen is not always the most pleasant experience.

“Director me wants to shake actor me,” Chilcoat confessed. “It kind of reminds me of why I never film my performances at my school, because nothing is ever quite as perfect as you think it was. The film itself, it has this fun, quirky kind of energy to it. Basically, whenever I watch it, I just want to shake younger me and be like, ‘Act better!’”

For Letterle, watching Camp these days is difficult, despite the fact that he’s now living a happy, healthy life. “I couldn’t watch it,” he admitted. “It was sad. That was me. That was a really good time in my life. Look at how good-looking and young I was.” Letterle paused again. “It was hard to watch.”

“It was just surreal,” his wife Danielle interjected. “It was you watching the former version of yourself.”

The last time Cutts watched Camp was in October 2013, when 54 Below (now Feinstein’s/54 Below) hosted a 10th anniversary screening. Graff was there, along with Chilcoat, Allen, and de Jesús, among other cast members. Both Graff and Cutts mentioned the strangeness of watching Camp with an audience that knew all the words. The film hasn’t reached Rocky Horror levels of midnight movie madness, but its fans are passionate and loyal. They made the 54 Below screening an interactive experience, one that gave Cutts a new perspective on the film.

“I can say that I appreciated it more,” he said. “I definitely get having so much raw talent now, because a lot of us were green, especially to film. There were a lot of people that had theater experience, but… It translated well. It’s so visceral how new it was for everybody, and it translated.”

It’s been 12 years since Camp was released. The film’s persistent queerness is no longer as revolutionary as it was in the early 2000s, but its influence remains.

Ryan Murphy, for example, was a big fan of Camp, as he once gushed to Graff. He went on to co-create Glee, which also followed the lives of misfit performing arts kids and was another major step forward for LGBT representation onscreen.

“I’ve been stopped so many times by kids who were affected by the movie and said that the movie saved their lives,” Cutts said. “I’ve heard it before and I felt moved by it, but just to hear it from more and more people is overwhelming. I know that it is a necessary thing for us to be involved in that way, and I’m glad that [Camp] was doing that when I wasn’t even aware.”

The effect of movies like Camp (and shows like Glee) is that queer people are more mainstream than ever. Of course that’s a good thing, but it’s something Graff has struggled with while working on the forthcoming Camp sequel. He said the theme of Camp 2, whose Indiegogo campaign will launch early next year, is “how normal everything has become that was so outlaw then.”

“There’s a danger in losing your outlaw status,” Graff explained. “The trick has always been to make the box bigger, not to figure out how to fit inside the preexisting box. It’s not about aping straight conventions if you’re the gay kid.”

But while queerness itself might be inching more and more toward “normalcy,” there will always be those who don’t fit in — whether because they can’t or because they don’t want to. And they shouldn’t have to, as Graff stressed in his original screenplay for Camp: Uniqueness is an asset. Camp is a film about teaching young people to sing out, to showcase their strengths and weaknesses, and that they can be celebrated without ever having to conform. No matter how inclusive society seems to be now, there will always be those on the fringes. And for those outcasts, regardless of how much time passes, Camp’s subversive pleasures will always be richly needed and undeniably valuable.

“It’s so great to be able to share that you can be weird and you can be a total mess if you want to be,” Chilcoat said, “and somebody is still going to care about you.”

That’s a sentiment that Graff has kept in mind as he works toward bringing Camp to a new generation with his sequel, which he noted is “not a retreat from what the first movie was,” but rather “trying to kick the ball further down the field.”

“What about the kid who now lost the place where they didn’t feel isolated? That place now has its own rituals and normalcy. And if you don’t fit into it, you’re sort of back where you started,” Graff said. “But one will always find one’s own community. [The outcasts] find their own within the larger whole.”

CORRECTIONS

Ty Burr wrote the Boston Globe review of Camp. A quote misattributed the critic.

Camp 2 will be funded via Indiegogo. A previous version of this article said it would be through Kickstarter.

Randy Graff is Todd Graff's cousin. An earlier version called her his sister.