Care for mental health patients is suffering severely as a result of cuts to the sector, a new study by independent healthcare charity The King's Fund has said.

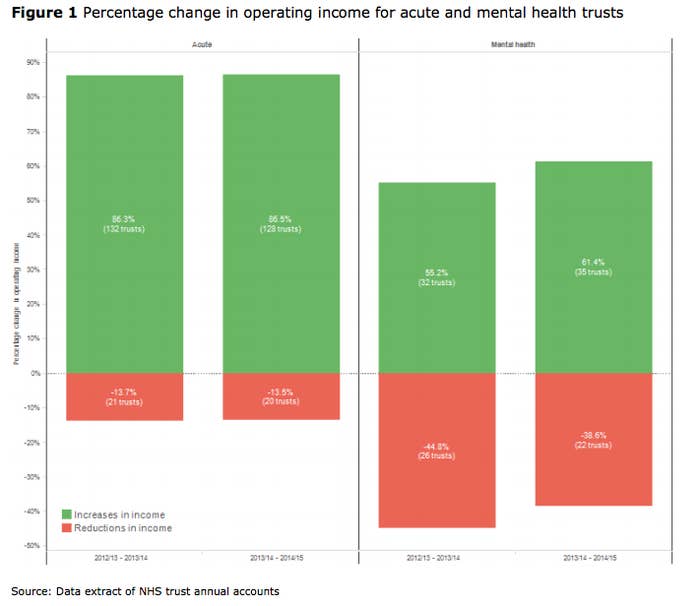

Despite David Cameron's call to create a "parity of care" between mental and physical health, around 40% of mental health trusts have seen a cut to their funding in 2013-2014 and 2014-15, while in the acute care sector, 85% of trusts have seen their income increase, the study claimed.

However, the minister responsible for mental health, Alistair Burt, said in a statement that the government has "given the NHS more money than ever before for mental health, with an increase to £11.7 billion last year".

But the study suggested that this was still not enough, calling a shift towards less proven methods of self-managed care in order to reduce costs "a leap in the dark".

It said that additional responsibility was being placed on community health staff as a result of the merging of crisis-resolution home treatment teams and early-access psychosis services, meaning that the correct support wasn't always being provided to patients in crisis or with severe mental health problems.

Researchers felt that this reduced the quality of care patients experiencing severe mental illness received, with only 14% of patients saying they received appropriate care in a crisis.

The study also noted a 23% increase in patients being sent to areas away from their homes for inpatient care, while bed occupancy rates routinely exceeded expected levels.

"Historically, mental health services have often been the first to see their funding cut, so many trusts felt forced to look at what savings could be made through transformation programmes to pre-empt this," the author of the report, Helen Gilburt, said. "Trusts looked to move care from the hospital to the community, focusing on self-management and recovery.

"Few would dispute the intention and rationale for this – the problems arise with the scale and pace of the changes, which lack the necessary checks to evaluate their effectiveness and the impact on patient care."

In response the government has said it is doing more than ever to invest in front-line services for mental health.

"We have made it clear that local NHS services must follow our lead by increasing the amount they spend on mental health and making sure beds are always available," Burt said.

"We have made great strides in the way that we think about and treat mental health in this country. As well as providing care for those in crisis, it is right that we invest in helping people early on so they can avoid that crisis and manage their conditions at home rather than in hospital."

However, Stephen Dalton, chief executive of the NHS Confederation's Mental Health Network, told the BBC's Today programme there is a "yawning gap between rhetoric and reality when it comes to mental health policy in England".

He said that mental health policy had become "a spectator sport with everybody from the prime minister to NHS England standing on the sidelines talking about what should happen, whilst local services actually aren't seeing any new funding and in fact are being cut."

The @TheKingsFund report on #mentalhealth today is vital, but we shouldn't forget all that is being done. @BBCNews

Luciana Berger, Labour's shadow minister for mental health, agreed with the suggestion that there was a disparity between the government's promises and real-world care.

"Ministers have failed to translate their warm words on mental health into progress on the ground. Instead, they have presided over service cuts, staff shortages, and widespread poor-quality care," she said in response to The King's Fund report.

"It's not enough for David Cameron to talk of 'parity of esteem' for mental health. He and his government must now accept their failings and urgently set out what action they will take to put this right."

Norman Lamb, former mental health minister and Liberal Democrat spokesperson for health, said: "For far too long mental health services have suffered from underfunding and political ignorance, undermining the desperate need to treat mental health issues quickly and sensitively."

Shocking report out today from @TheKingsFund about #mentalhealth services - cuts are damaging quality of care https://t.co/dEWCVL2ULe

Mental health charity Mind also questioned the government's commitment to giving mental and physical health an equal footing in light of the report, which chief executive Paul Farmer said "lifts the lid on the true state of NHS mental health services".

"We hear every day from people with mental health problems who tell us that support is getting harder and harder to access as services shrink while demand escalates," he added.

"If people don't get the help they need, when they need it, they are likely to become more unwell and need more intensive – and expensive – support further down the line.

"Failing to deliver the right care isn't good for people and it's not good for the NHS. We echo the King's Fund's call for more funding for NHS mental health services; after decades of neglect and five years of cuts, services are in urgent need of significant investment."

Generic community health teams provide an important service in the ongoing care of patients with mental illness, and a spokesperson for the Department of Health said that they were in no way seen as an alternative to front-line services where patients were in crisis.

Responding to The King's Fund's findings that patients were suffering as a result of extra pressure being placed on these teams, Brian Dow, director of external affairs at the charity Rethink Mental Illness, said: "This largely comes down to the question of whether support is being designed around the needs of people with mental health problems – or is it about being driven by attempts to cut costs and find the cheapest way forward?"

He echoed that there was "no doubt" that a lack of funding had a negative impact on services and the support people with mental illness received.

The merging of crisis teams with generic community health teams "could mean a very different outcome for someone who, for example, has schizophrenia and is in the midst of a crisis, hearing voices telling them to harm themselves," Dow said. He warned that while some areas would have access to trained professionals with expertise to deal with that level of crisis, others may not.

A spokesperson for the Department of Health (DoH) said beds must always be available for those who need them:

"We have set out in our mandate to NHS England that plans must be put in place to ensure no one in mental health crisis will be turned away. The Crisis Care Concordat makes it clear that local commissioners should commission a range of mental health services that respond rapidly and appropriately to a person in urgent need."

Responding to the study's claim that only 14% of patients felt they had received appropriate care, the DoH said they have asked the Care Quality Commission watchdog to look at the quality of crisis care "because we know improvements need to be made".