"Please take this from me, I don’t want to be gay."

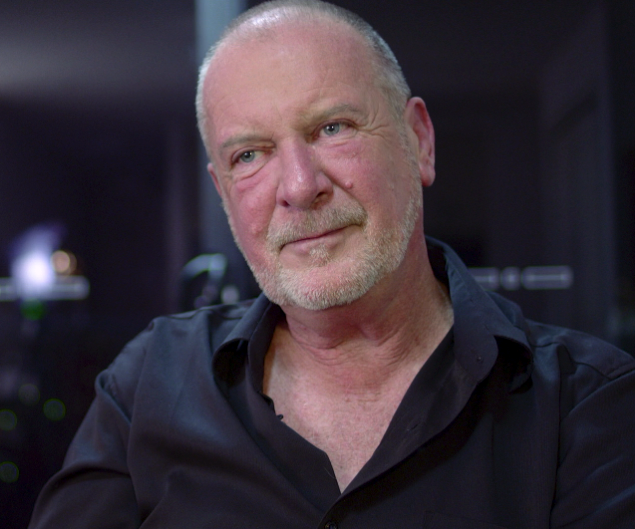

Brisbane man Johann De Joodt knows first hand the horrors of gay conversion therapy.

A participant in numerous programs designed to purge his homosexuality during his twenties and thirties, De Joodt adopted a traumatising routine of church, sin and repentance that looped on repeat every week for 15 years.

“Sunday, I was going up to the altar, crying out to God,” he said. “Monday, I would sin by having sex with another man, and then beat myself up to a pulp so by Saturday I was suicidal. I’d manage to get myself to church on Sunday and then do it again, every week.”

“That was basically my life.”

"When a church leader says being gay is an abomination, people say, 'you’re talking about my uncle who I love very much.'"

The question of whether conversion therapy works was answered long ago: it doesn’t. Leading psychological associations in Australia and around the world have denounced therapy that attempts to change sexual orientation. Earlier this year, a report from the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights called for nations to ban the practice, describing it as “unethical, unscientific and ineffective and, and may be tantamount to torture”.

Partly as a result of these strident denouncements, the prevalence of such therapy has significantly declined in Australia. Around 40 providers across the country in 2000 have dwindled to just a handful still in action today.

“There’s very little left. It’s in disarray,” says former pastor Anthony Venn-Brown. Venn-Brown, who has himself been through reparative therapy, is the most prominent voice on conversion therapy in Australia. He now works as the founder and CEO of Ambassadors and Bridge Builders International (ABBI), a group that works to combat ignorance and hostility between the LGBT community and churches.

Speaking to BuzzFeed News at a cafe in Waterloo, Sydney, Venn-Brown suggests another part of the decline is due to a growing acceptance of gay people in wider society – which, of course, includes churches too.

“More people are out, churchgoers have got gay sisters, brothers, colleagues, friends,” Venn-Brown says.

“When a church leader says being gay is an abomination, people say, 'you’re talking about my uncle who I love very much.'”

The most thriving ex-gay programs are in Queensland, where Liberty Incorporated runs alongside the smaller Triumphant Ministries Toowoomba. Sydney-based Living Waters, one of Australia’s longest-running ex-gay programs, closed down last year.

There are also groups that advertise themselves as providing pastoral counselling on dealing with same-sex attraction, but clarify they do not attempt to change sexual orientation. These groups include Liberty Christian Ministries in NSW, and Renew Ministries in Victoria.

However, perhaps due to the stigma now attached to conversion therapy, there is little public information available about the funding, treatment methods and numbers of clients for each of these organisations. While Venn-Brown estimates that the programs would get “very few referrals” these days, their relative invisibility serves as a shield to such information. “We’ll never know the exact numbers,” he says.

At the heart of religious conversion therapy is “a strong belief in an all powerful God”, says Venn-Brown. Programs use a number of methods to exploit this belief, convincing participants that homosexuality is not what God wants for them. Venn-Brown went through dramatic exorcisms, where he convulsed on the floor for hours as pastors gathered around him, screaming for the demon of homosexuality to exit his soul.

Other methods include group and personal counselling, where homosexuality is posed either as a shameful habit that can be broken or an affliction, harking back to the days when it was considered a mental illness.

Johann De Joodt bristles at the description of gay conversion therapy as “nearly dead”.

“Conversion therapy hasn’t ended in Australia,” he says. “It is alive and well.”

De Joodt came to Australia from Sri Lanka in 1984. A few years later, he found himself heavily involved in the Assemblies of God Pentecostal church movement – now known as Australian Christian Churches – and struggling with his sexuality.

“I went to confess my sin of homosexuality to my pastors,” he says. “I was pretty involved in church life, and the pastor recognised that there were a few other people in the church who were struggling with their sexuality as well.”

De Joodt started the Living Waters ex-gay program in 1990. This was the first of many programs he went through, and when his weekly routine of church, sin, and self-loathing began. It wouldn’t end until 2005.

For years, De Joodt prayed the gay away as various pastors attempted to cast the demons of homosexuality from his soul. He was told his sexuality was a habit that could be broken and changed, that he was gay because he had been sexually assaulted as a child and lacked a decent father figure. He enrolled in courses on self-esteem, and learning how to say no, and did hours of counselling. He prayed, week after week after week.

Unsurprisingly, Johann stayed gay. But the years he spent in therapy ate away at him in other ways. “My health...” Johann starts, then pauses. “I am on antidepressants. Everything I’ve been through has stuffed up my mental health.”

"You were either Christian and heterosexual or you were gay and going to go to hell"

Since 2000, twelve peer-reviewed, primary research studies have found conversion therapy is harmful to mental health. A Columbia Law School project collating conversion therapy research found that among people who had undergone the treatment, there was a prevalence of depression, anxiety, social isolation, decreased capacity for intimacy, and suicidal thoughts and behaviours. “There is powerful evidence that trying to change a person’s sexual orientation can be extremely harmful,” the researchers concluded.

“People have taken their lives, they are now on pensions because they can’t function in everyday life,” says Venn-Brown. “There are PTSD issues, they’ve been harmed mentally, they’re traumatised.”

This manifest trauma and pain is why Venn-Brown has devoted his life to combating ignorance between the LGBT and faith community through ABBI. His daily grind is a softly-softly approach that coaxes people of faith and the LGBT community closer together. “The biggest challenge is fear,” he says without hesitation.

In the past – and in conversion therapy – being gay and being a Christian were seen as incompatible. Venn-Brown says that when he was going through therapy in the 1970s and ‘80s, there was “nobody who believed there was such a thing as a gay Christian”.

“You were either Christian and heterosexual or you were gay and going to go to hell,” he explains. “The gay Christian movement was just beginning to grow then.” After coming out in 1991, he left the Christian faith for six years – but then returned to it after realising being a gay Christian was possible. “There are things [in Christianity] that I can take, that are very real for me,” he says. “Forgiveness, sowing and reaping, having purpose.”

As attitudes have changed and churches become more permissive, many LGBT Christians have been able to reconcile their faith with their sexuality and gender identity. However, a damaging rift still exists between the two communities, with years of betrayal from religious organisations leaving LGBT people fearful and unwilling to engage. Those hurt most by the hostility are LGBT Christians, who are often left feeling as though they belong in neither camp.

“Just as Christians have stereotyped all LGBT people, some LGBT people have stereotyped all Christians,” says Venn-Brown. “We get called perverts, abominations, they get called bigots and haters. And that doesn’t get us anywhere, just sitting back in our camps, our tribes, throwing barbs at each other.”

It’s obvious the division is unhelpful – but is being called a pervert really on par with being called a bigot? Venn-Brown pauses before answering, in short, no.

“It’s about the perception – we will often hear, a Christian like [Australian Christian Lobby Managing Director] Lyle Shelton or [Christian Democrats leader] Fred Nile say ‘I am not homophobic’. But everything that comes out of their mouth is completely homophobic. They just don’t understand what homophobia is, because they’ve never experienced it,” he says.

“We come from our own hurt, and our own pain. And we react, as any human would, when cruel and nasty and insensitive things are said by these people.” He switches into the second person, speaking directly to those who have hurt him. “You don’t know what that does to us, because you’ve never experienced that. You don’t know what it feels like.”

But matters of blame and hostility aside, Venn-Brown is convinced his approach of “dialogue and respect” is best. He knows both the LGBT and the faith community intimately, and says church communities do not respond to “aggressive” activism.

“I introduced [Hillsong Pastor] Brian Houston to a guy in his church who had been referred to somebody [for conversion therapy],” says Venn-Brown. “I got him and his parents to write a letter, Brian met with him.”

Later, it emerged that Houston had issued a directive to all Hillsong staff to never refer anyone to these programs.

“I’ve talked with people who are major religious leaders in Australia. It’s been a journey of ten years for some of them,” Venn-Brown says. “I’ve seen progress, but not where I would want it to be. In every human rights movement, it’s taken decades to shift. If you’re not in it for the long haul, it’s not going to work.”

"If people want to be so small-minded as to think that you have to be straight to get into heaven then I think they’re going to get a big shock when they do get to heaven"

ABBI has also pushed for the outlawing of conversion therapy in Australia. Although Venn-Brown describes the movement these days as “irrelevant” and “inconsequential”, he says a legislative approach would send a decisive message to individuals, to churches and to society that conversion therapy is a relic of the past.

However, politicians involved in LGBT law reform say a legal approach to ending conversion therapy is complex.

“There’s not much that can be done to target these organisations specifically at a federal level, other than continuing to tighten anti-discrimination legislation and look at the applicability of consumer law,” Greens senator Robert Simms tells BuzzFeed News.

If providing the therapy was considered a breach of the Sex Discrimination Act, it’s likely that the religious exemptions in the Sex Discrimination Act would protect conversion therapy providers. Under Australian consumer law, the religious and not-for-profit aspects of most conversion therapy programs would mean they are not considered “commercial in nature”. While such laws could be tweaked, says Simms, it’s unlikely they could be used as a mechanism to eradicate the therapy altogether.

Graham Perrett, a co-chair of the Parliamentary Friends of LGBTI People Working Group, says a federal law banning conversion therapy may be unconstitutional.

“In terms of section 51 on the powers of the parliament, I can’t see any head of power that would give the federal parliament any capacity to make gay conversion therapy illegal in Australia,” he says.

There are some legal avenues under state and territory law as well, with acts in all jurisdictions outlawing advertising of health services that are deceptive or misleading. It could also be possible to lodge a complaint with the Australian Psychological Society that their code of ethics has been breached.

However, there is no black and white policy solution to immediately ending conversion therapy.

“It’s all just prejudice welded onto quackery packaged by a religious organisation,” says Perrett.

“I think education is the best antidote.”

De Joodt’s conversion journey reached a fork in 2005. His conversion counsellor at the time, CEO of Liberty Incorporated Paul Wegner, told him “I can help you suppress your sexual desires, but I can’t help you change your sexual orientation”.

“I was like, ‘Well, what’s the point?” says De Joodt. “If you take a ball and try to push it in a bucket of water and let go, it’s going to eventually pop up.”

He came out, lost “a lot of people”, and left his Pentecostal church. He went to the LGBT-friendly Metropolitan Community Church for a few years, and then stopped that, too. But God is still in his life.

“I have days where I feel like a Christian, and there are other days where I feel like I hate God,” he says.

“I think I’ve resolved my sexuality with my faith. If people want to be so small-minded as to think that you have to be straight to get into heaven then I think they’re going to get a big shock when they do get to heaven.”

A pause, and then: “I think God is bigger than the box you put God into.”

It’s because of this new understanding of faith, says De Joodt, that he doesn’t relapse into wanting to be straight again. “I’ve come to a point where I believe I need to be honest before myself, and before my God.”

“There’s a famous saying, isn’t there?” He thinks aloud. “Change what you can change and leave the rest to God? Or something like that. Accept the things you can’t change?”

A quick Google search later, it becomes apparent De Joodt was trying to recall the words of the Serenity Prayer, brought into popular culture by its widespread use in Alcoholics Anonymous meetings:

God, grant me the serenity to accept the things I cannot change / The courage to change the things I can / And the wisdom to know the difference.

It took years of anguish, but finally, De Joodt has been granted that serenity. He knows the difference, too.

“If God wanted just another heterosexual, God could have created one, but instead God created me fabulous,” he says.

“My sexual orientation is something I cannot change.”

A spokesperson for Liberty Christian Ministries declined a request to be interviewed for this piece. Requests sent to Liberty Incorporated and Triumphant Ministries Toowoomba were not responded to.