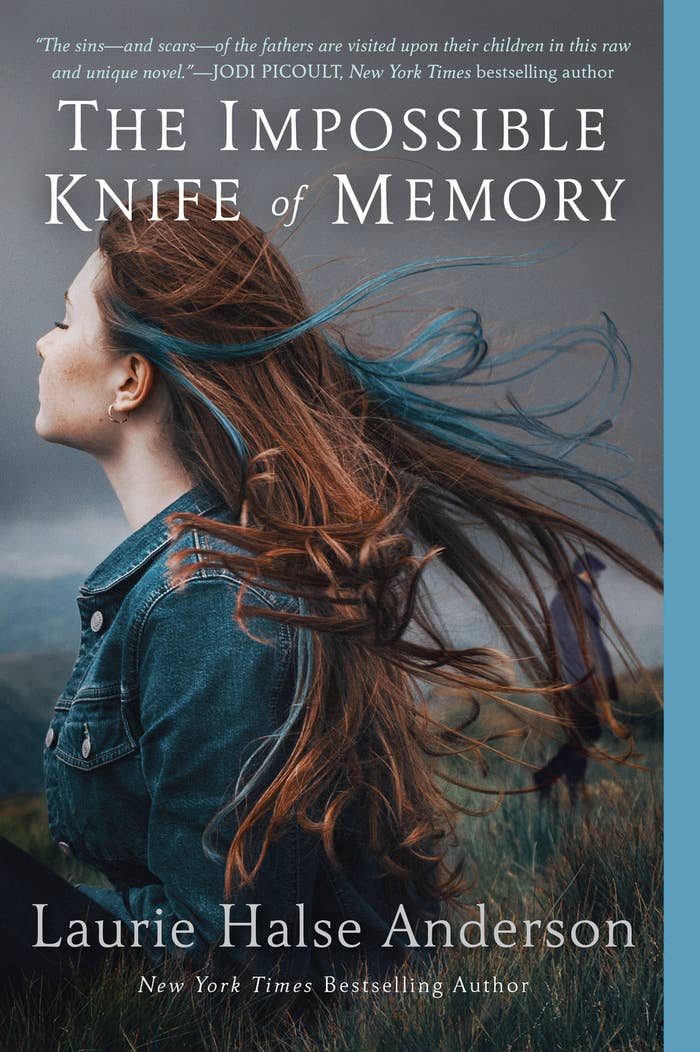

Laurie Halse Anderson has been an important and beloved voice in young adult literature since her debut novel, Speak, was published over 15 years ago. Since then, she's gone on to write five more YA novels, four historical fiction novels, and eight children's books. Last year, Anderson published The Impossible Knife of Memory, a story about a high schooler named Hayley Kincain whose father is a war veteran who struggles with addiction and suicide. The author isn't afraid to tackle other topics around mental health, eating disorders, sexual assault, and other serious subject matters in her literature.

BuzzFeed had the chance to catch up with Anderson and discuss The Impossible Knife of Memory, the importance of catering to teenagers during the crucial time of adolescence, and what she wishes she could tell her younger self.

On the inspiration behind The Impossible Knife of Memory:

Laurie Halse Anderson: With most books, when you're writing it, of course you think that the idea just hits you. When you have some hindsight you can see exactly where it came from. One thread was growing up with a World War II veteran father who had PTSD from his experience. My dad lived to be 86, and those memories were seared so deeply, they caused him pain for all of those years, and he became an alcoholic, and there were a lot of family struggles, like many families of veterans have struggles.

The second piece was when my nephew left the Army after several tours in Iraq and Afghanistan. Watching him try to reintegrate into civilian society really helped me understand my dad from a completely different perspective, and that got me thinking about the kids whose fathers and mothers were the new veterans from this war, and what kind of scars would they have that their kids couldn't see, that would make family life a challenge? The third part for me goes down to a little girl in Dallas, Texas. A couple years ago, I was speaking at her school, and she said to me, "Miss, are you ever going to write about a love story? Wouldn't it be nice to write something that wouldn't make you cry all the time?" That's what I tried to do with this one — it was a little bit of a different spin for me.

On relating to the story's main character:

LHA: There's this part about writing, you can analyze technique and craft and inspiration six ways from Sunday, but at some point magic kicks in, and you're like, "Wow, I have no idea where that line just came from, but I really love it." There are definitely parts of Hayley's experience that are mine. When you read that fear that's in her about when she goes home every day afraid of what she's going to find, the fear of having a suicidal parent — that was absolutely my experience. But I didn't start writing until her voice started cropping up in my head. This is the magic part; it's kind of strange, too, but the characters really do talk to you. So it was a little bit of me, but mostly her.

On reader response:

The book has been out for about a year now. What kind of responses have you received from readers?

LHA: People who were first introduced to my books in high school are now in their twenties and some of them even in their thirties, so they kept reading me. But I think maybe because of the PTSD tie-in and because so many people come from families where one parent or sometimes both are struggling with mental health issues, you don't just leave that when you leave home. That stays with you. So a lot of the readers from this book were older than I had anticipated. I've had feedback from a couple generations of readers. It's been really nice.

On offering solace through storytelling:

What do you hope readers take away from the story?

LHA: I'm one of the writers who hesitates to think messages are ever a good thing if you're trying to be artistic. My job is to tell a good story, and a reader is a very important part of the equation. This is why not all people love all books, because you can't write a book that's going to speak to the condition of every heart. But if I did my job telling this story well, there will be some readers out there for whom it will resonate deeply, and you always hope for that. Having gotten some feedback from readers, I know there's a lot of teens out there — which is such a lonely time — who think they're the only person who has a mom or a dad who's getting drunk, or who's just checked out for whatever mental health issues, and as you're trying to become an adult yourself, to have the adults closest to you not be there the way that we would hope, that's very painful, and it's confusing to make sense of it when you're a teenager. I do hope, for those readers, that the book will offer some solace.

On perspective:

LHA: The problem is, you've got almost two main characters in this book — Hayley and then her dad — and so if we just looked at [Hayley's dad] through Hayley's eyes, he's a jerk. He's a drunk, he gets high, he doesn't take care of her, and he loves her, we know that, but he's a mess. I wanted my readers to understand and have empathy for him and his struggles. The grand theme of this book is memory and how memory cuts both ways; it can either provide you with tremendous strength and a foundation to carry you through your life, or it can be a demon that just ruins your present and your future because you can't let go of the past. And so, hearing from him and understanding the memories that are scarring him I thought would bring some balance to the book.

On hard truths:

Why do you think it's important for YA novels to address mental health issues like depression, suicide, anxiety, sexual assault, and all these other heavier topics?

LHA: I grew up as a teenager with parents who were disconnected from me for their own reasons, so I remember so clearly that confusion and that sorrow. I could go on for days about ... our disrespect and disregard for adolescence in American culture. Americans are all about loving kids when they're small and portable, but for some reason … boy, do we abandon our teens. We abandon them in families, we abandon them as a culture, we don't do a great job in most high schools of educating them properly. We disrespect them, and at the time when they are in most need of good, fun, loving, trustworthy relationships with good adults, we step away. And that's really stupid and awful. So I try to write stories that tell the truth about hard things because kids need to know it; the world is hard and it will kick your ass if you're not careful.

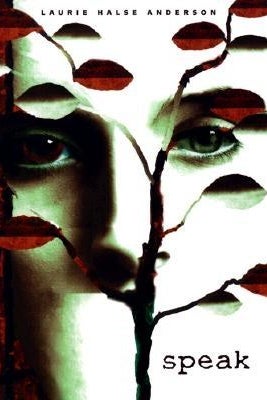

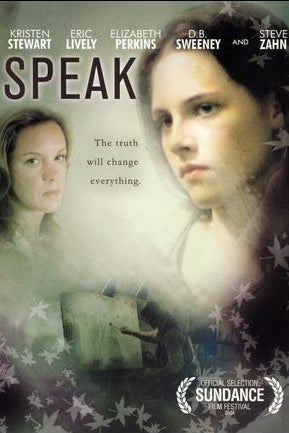

On the enduring relevance of Speak:

Last year Speak celebrated its 15th anniversary, and even though a considerable amount of time has passed, the story is still so relatable all these years later.

LHA: Even more so, I think, because the kids who are now reading it are usually reading it in school, and they weren't even born when the book first came out. There were a couple of years when I naively thought, Maybe the book will fade away because feminism is having an impact on American culture and we're raising our boys up better and maybe incidents of sexual assault will go down. And wasn't I just wrong? I would love for the book not to be topical anymore, but that would mean that we've figured this crap out, but we haven't.

On sex and consent education:

LHA: It's been super gratifying and powerful, though, to be a part of a movement in our culture, to talk about consent in particular and to try and get adults to just grow up. If you're going to take on the tough job of being a parent, that means you have to find the courage to talk to your kids about things like sex. You teach them how to look both ways before they cross the road; you also have to teach them a couple of other things. So 15 years on, I'm surprised, frankly, that the book is as current as it is, and a little horrified for all the victims of sexual assault. But I'm very proud that the book can help. I know it does, because I still hear daily — for 15 years I've heard daily —from survivors of sexual assault.

On the importance of YA fiction, for both teens and adults:

LHA: First of all, I think some of the finest writing in American literature today for the last several years has been in young adult literature. I know a lot of people who write YA books, and we really care about our readers. You don't go into children's fiction to make a lot of money; occasionally someone will really hit it out of the park and we'll feel really proud for them, but it's not what you call a steady income. So you go into it because you care about kids; specifically for YA authors, you care about teenagers.

I've been an adult for a while now, and I've met my share of very unhappy adults, and it's so sad. When I meet adults who are broken, it often, when you get to know them, is tied down to the fact that they didn't cross that bridge from childhood to adulthood successfully. Something went wrong in adolescence, and I have this theory that we go through many adolescences in our lives, these liminal changes from our developmental age to the next. But then also the emotional challenges that then come with these changes.

On why more adults should read YA:

LHA: It gives them insight into what their kids and the next generation of Americans are dealing with, which is important. It can also give them insight into some of their own stuff, some of their own sadness and sorrows, and shine a light on maybe some work that they need to do emotionally, which is very helpful. And also, the writing's amazing.

On diversity in literature:

Are there any specific kinds of stories or topics that you think YA needs to do a better job of telling?

LHA: We need more stories about kids who aren't white. I'm a huge fan of the We Need Diverse Books campaign. Kids need to see themselves in books. They need to see kids who reflect their economic background, their ethnic background, their religious background, their sexual orientation, their confusion about their sexual orientation, their gender awareness, their lack of gender awareness; it's like you don't exist if you don't see yourself, particularly at a point in your life when kids are trying to define themselves.

How do we expect them to do a good job, a job that's grounded in integrity, when we don't show them different ways of being, different examples of how people are? That's on us, again. It's on the adults. I think that's what's really missing — not only all the varieties of adolescence and children's experiences in the United States, but I would love to see a lot more YA fiction in translation from other parts of the world.

On the author's advice to her younger self:

If you could go back in time and tell your teenage self one thing, what would it be?

LHA: I would've told myself to go out for the basketball team. I'm not a small woman, and I love basketball. My girls play basketball and it's so much fun, and I love the game. I was kind of a shy and very angry teenager, and I really didn't get along with the girls on the team. But looking back on it, probably it wasn't that we weren't getting along at all, I think it was that I didn't know them well and I was emotionally so defensive all the time that I didn't let people in. And I think that if I had gone out for that team, I would've gotten to know them better and we probably would've gotten along well enough to play a game of basketball. And I think that would've made me a better person.