Tennis star Maria Sharapova has admitted to testing positive for meldonium, a drug banned by the World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA).

Sharapova is not the only one to have tested positive for the drug.

Russian ice dancer Ekaterina Bobrova, Russian cyclist Eduard Vorganov, and Ukrainian biathletes Olga Ambramova and Artem Tyshchenko have all reportedly failed drug tests because of meldonium this year.

What is meldonium?

Why was it banned?

WADA decided to ban meldonium following a period of monitoring the drug's use in 2015. A study, which has now been published in the British Journal of Sports Medicine, found "widespread and inappropriate use" of the drug among athletes who are generally healthy.

The researchers investigated meldonium use during the Baku 2015 European Games and discovered that while only 23 of the 662 (3.5%) athletes declared that they had used the drug, 66 of the 762 (8.7%) urine samples analysed during the games tested positive for the drug. Only six of the 21 sports included the games did not have any competitors who had used the drug.

Where is it available?

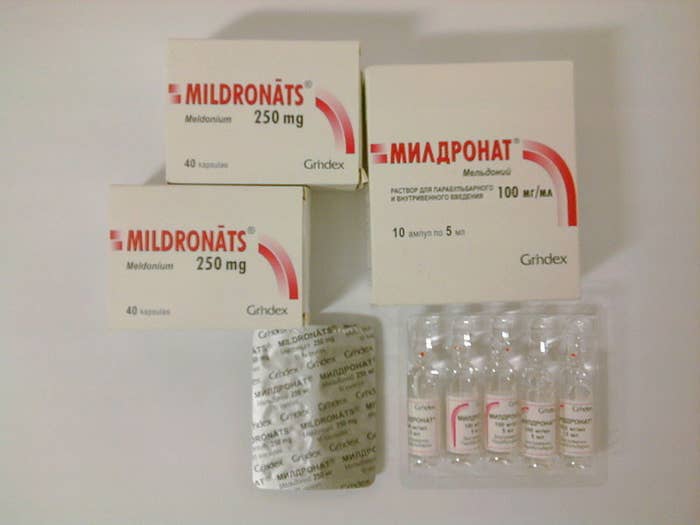

Meldonium is not approved by the Food and Drug Administration, so you can't get it on prescription in the US. It's not available in the UK either. You can, however, get it prescribed or buy it over the counter in many eastern European countries. The Associated Press managed to buy some in Moscow, Russia, on Tuesday.

What is the drug for?

The drug is designed to treat heart conditions by stopping the buildup of damaging by-products.

When someone has a heart condition that reduces the flow of blood to the heart it reduces the amount of oxygen available to the heart. But the organ will still try to burn fat and ends up creating by-products that damage it in the long run.

"The idea in heart patients is you block this path, and during periods of reduced blood flow you wouldn't build up these by-products," Dr Michael Joyner of the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota, told BuzzFeed News.

What else does it do?

A paper published in the journal CNS Drug Reviews says that the drug appears to improve mood in patients and claims it combats lack of energy, dizziness, and nausea. The paper also cites an animal study that found the drug protected against stress and increased the length of time mice and rats could tolerate "prolonged forced swimming".

What effect does it have on healthy people?

The drug's manufacturer, Grindeks, has said that it "improves physical capacity and mental function" in healthy people. But Grindeks told the Associated Press on Tuesday that it would not enhance an athlete's performance, and might even hinder it by causing the release of energy by breaking down fat to slow down.

Does it actually help athletes' performance?

The argument appears to be that, if it helps the hearts of cardiac patients recover, it could help the muscles of an athlete recover. "But in normal healthy young people, in general the muscle recovers just fine," says Joyner.

How big any of the drug's effects are is unclear. "There aren't a whole lot of randomised control trials about this stuff," Joyner told BuzzFeed News. "If this stuff works and has a performance-enhancing effect, it's going to be small – it's not going to be like EPO (erythropoietin), or steroids, or amphetamines."

Joyner told BuzzFeed News the lack of interest from the rest of the world made him suspicious of the drug's effectiveness, too. "No large drug companies in western Europe, America, or Australia appear to have tried to license this compound to treat patients. The biggest markets are in the West, so if the drug was so good why wouldn't it be used here?"

How is it typically used?

Grindeks told the Associated Press that a typical treatment course of the drug is four to six weeks, and that a course can be repeated two or three times in a year if necessary.

Sharapova said she begun using it in 2006 and has been using it since.

But that discrepancy shouldn't necessarily raise suspicions, says Joyner. "It may well be that it's typical to use acutely in a patient [for four to six weeks]. But once a drug is approved, physicians can use it for all sorts of reasons, that may or may not be what it was intended for. There may be some Russian physician who thought, Well, if it reduces fatigue and helps the heart recover, it'll help her muscles recover faster."