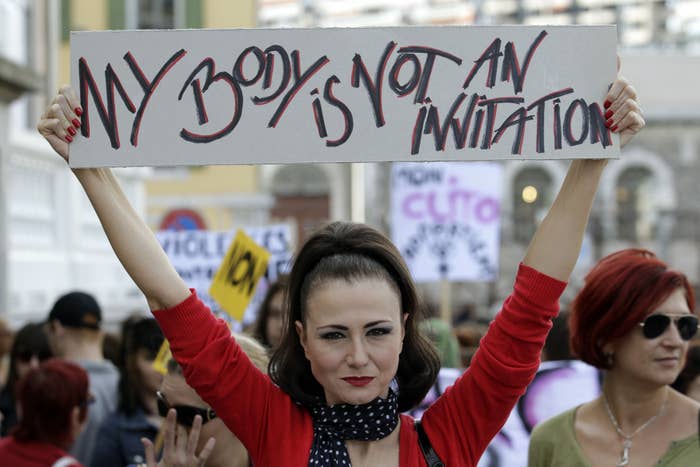

The term "rape myths" — meaning prejudicial stereotypes about sexual assault — was coined by feminist academics decades ago. Yet, we still see the same false assumptions playing out across Canada.

1. Myth: Rape is committed by strangers.

Empirical evidence contradicts the widely-held, stereotypical idea that sexual assault is a violent attack by a stranger in a public, deserted place, in which the victim is a morally upright woman who is physically injured while resisting.

It shows that most sexual assault crimes – 80% in 2002 in Canada – happen where the accused is known to the survivor: 41% of survivors were assaulted by an acquaintance, 10% by a friend, and 28% by a family member. Only the remaining 20% were assaulted by a stranger.

But despite the evidence – the stereotype persists that assaults are perpetuated by strangers. A recent survey of campus police officers in the United States found that a pre-existing relationship between a sexual assault complainant and the accused was among the biggest circumstances that cast doubt over the complainant's credibility.

2. Myth: Rape is always extremely physically violent, and always leaves physical evidence.

Violent attacks by strangers are rare. Physical violence is overt and easy to recognize. Other means of coercion may not be so obvious.

In cases where perpetrators are acquaintances, friends, and family members, those who commit the crime have access to coercive tactics other than physical violence. And coercion that is not physically violent can be just as forceful and disempowering.

3. Myth: All police officers understand the legal definition of sexual assault.

Police are often the first point of contact between sexual assault survivors and the justice system. But studies have shown that stereotypical ideas about sexual assault can influence police interactions and evaluations of complainants.

One study from the late 1990s asked police officers to write, in their own words, how they define sexual assault.

Officers' responses included:

* "Rape is just rough sex that a girl changed her mind about later on. Technically, rape is a sex act done by the use of force, but so many girls are into being forced, that you can't tell the difference and you wouldn't want to convict an innocent guy."

* "What if someone has had sex 20 or 30 times over a 3-month period. Then one night they say 'no.' Should this be rape? I don't think so."

* "Sometimes a guy can't stop himself. He gets egged on by a girl. Rape must involve force – and that's really rare."

Another more recent study found campus police officers at a Texas university believed survivors of sexual assault lie at a much higher rate than victims of other kinds of crime. Statistics show that the number of false reports for sexual assault is similar to those reported for other crimes (6% to 8%). But the researcher found that more than half the Texas officers in the sample believed that between 11% and 50% of rape complaints were false allegations, and 10% believed that 51% to 100% of women lied about being raped.

4. Myth: Judges avoid rape myths when deliberating cases.

There are several moments in Canadian legal history that changed how judges do and do not look at a complainant's sexual history.

In two cases in 1992, the Supreme Court decided that excluding a complainant's sexual history infringed on defendants' Charter rights to "full answer and defence." Survivors' sexual histories, it said, may be relevant to defendant's cases.

In her dissent, Justice Claire L'Heureux-Dube wrote that "rape myths" persisted as "obstacles for complainants" – and it was a rape myth to consider survivors with sexual experience less credible than those without.

In 1992, parliament amended the Criminal Code to prohibit using a complainant's past sexual history. But several years later, an Alberta judge acquitted a man accused of sexual assault – Ewanchuk – by referring to the complainant's sexual experience as evidence that she is likely to have consented.

In the Ewanchuk case, Judge John McClung wrote that the 17-year-old complaint did not "present herself [to the defendant] in a bonnet and crinolines. She had told [Ewanchuk] that she was the mother of a six-month old baby, and that, along with her boyfriend, she shared an apartment with another couple."

He implied that, because of the complainant's sexual history, she was more likely to have consented and was thus less worthy of belief.

The Supreme Court rejected Ewanchuk's defence of "implied consent" and ruled that the he did not take steps to establish the existence of a "yes," and that it was not enough that he did not hear a "no."

In the Supreme Court ruling from 1999, Justice L'Heureux-Dube wrote that Ewanchuk was "not about consent, since none was given. It [was] about myths and stereotypes." The groundbreaking case rejected the stereotype that survivors must fight their way out of assaults using physical force to be credible. It also established that it was necessary for the accused to show evidence of a reasonable belief in the existence of a "yes" rather than the absence of "no."

Ewanchuk has since been most clearly and consistently applied in cases where the complainant expressly communicated a lack of consent. But inconsistencies in application remain. Last year a federal judge in Alberta asked a teenage sexual assault complainant why she "couldn't just keep [her] knees together."

5. Myth: Racism and other prejudices never influence how sexual assault is reported, investigated, or tried.

Canada does not collect race-based data but there is evidence that people from minority backgrounds face higher barriers in seeking justice, including in sexual assault cases.

Dozens of women from Vancouver's downtown east side went missing before police apprehended Robert Pickton. An inquiry found that the Vancouver Police Department's investigation into these disappearances was compromised by bias against the survivors.

In Canada, sexual assault survivors from racialized communities may be less likely to report assaults if they feel their communities are already targeted disproportionately by police. They may feel that racial bias will influence the way law enforcement treats them as a complainant.

Indigenous women report higher rates of sexual violence, as do women living with disabilities.

6. Myth: "Real" survivors of sexual assault will report it.

In Canada, the Violence Against Women Survey conducted in 1993 found that only 6% of sexual assaults reported in the survey had been disclosed to police.

A report from Justice Canada found that' negative views of the criminal justice system's response to sexual assault was the most common reason survivors gave for not reporting an assault. Almost 9 out of 10 survivors of sexual assault in Calgary felt that "reporting to the police would mean that a [woman's] personal life would be dragged through the mud." Seventy percent believed their "actions and decisions would be judged as inappropriate."

A study from 1984 conducted by researcher Linda Williams identified conditions under which survivors of sexual assault were most likely to report their experiences. The survey of 246 female sexual assault survivors – all of whom contacted a Seattle rape crisis centre over the course of 16 consecutive months in the early 1980s – found that women were most likely to report a sexual assault to police if the perpetrator was a stranger, and if the assault resulted in serious physical injuries.

Three-quarters of women who sustained physical injuries reported the assault to police, and 63% reported it if the perpetrator was a stranger or an acquaintance — whereas 44% reported it if the perpetrator was a relative or a friend.

7. Myth: Most people understand what "consent" means.

A recent poll by the Canadian Women's Foundation found that 67% of respondents did not know the legal definition of consent even though 96% agreed that sexual activity should be consensual.

8. Myth: "Real" sexual assault is a rare crime.

One in every four Canadian women will experience sexual assault in her lifetime and half of all Canadian women have survived at least one incident of sexual or physical violence, according to a 1993 Stats Canada survey. Almost 60% of these women were targets more than once.

Most assaults (60%) occurred in private homes, with more than a third occurring in the victim's home.

9. Myth: Sexual assault survivors are always able to identify their experiences as such.

One study in the 1980s surveyed over 2,000 college women and found that 13% of them had had an experience that met the legal definition of rape. However, of these women, almost half (43%) answered "no" when asked, "Have you ever been raped?"

In other words, women who think of sexual assault as random stranger attacks in dark alleys do not always identify nonconsensual sexual activity as assault.