"It doesn't leave you, even when you have a moment alone," Tariq Jahan says. "Memories of that night, they'll always be there."

He pauses. His eyes fixate on the ground. "They were too young to have lost their lives," he sighs. "To have no justice is immoral." His hands begin to tremble.

In August 2011, riots that began in London as a result of the shooting of Mark Duggan spread to a number of Britain's major cities.

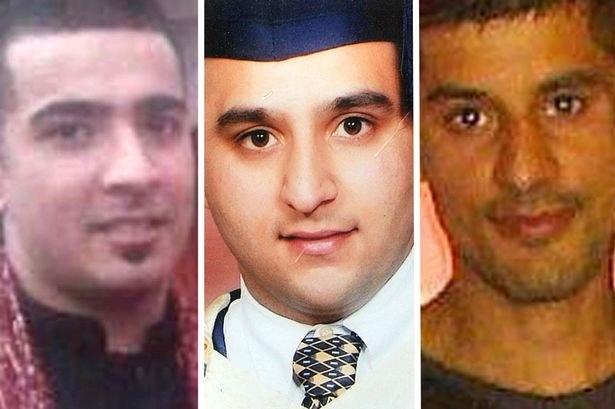

In one of the most high-profile moments, on 10 August, Haroon Jahan, 21, and brothers Shahzad Ali, 30, and Abdul Musavir, 31, were killed after being struck from behind by a speeding car holding eight men suspected to have been involved in the rioting.

Although Tariq Jahan looks healthy – with a clean grey beard and well-kempt hair – there are bags under his eyes. He admits that despite the time that's passed, remembering the deaths of his son and his friends remains a painful experience.

The boys had been defending a local business on Dudley Road – a stone's throw from their home in Winson Green – alongside other residents of the local community, most of whom were Asian.

Jahan has seen his son's death on video more than 20 times, but what haunts him more are the memories of finding Haroon lying on the ground, and being unable to resuscitate him.

"When I heard the impact of the car – it was just a flash – I thought it had hit some bins or something," he says.

"But after, my first reaction was to run [to the scene] and do first aid. A friend tried to revive one of the boys, so I ran to where the other two men were, and when I went over there, and turned one of the bodies over, I found my son – I found Haroon.

"I spent a couple of minutes trying to help him, but he didn't have a pulse. I realised eventually I couldn't help him – he was too far gone. Every time I breathed in, blood would come out of his mouth.

"After that, I went home to my wife, and told her what happened, and that we were going to the hospital. She believed he'd make it, but... I knew. I knew he was gone."

Since the riots, the families of the men killed have felt let down by the British authorities, which they claim have failed their sons.

Left: Tariq Jahan holds a picture of his son Haroon in Birmingham on 10 August 2011 near the scene where Haroon was killed. Right: Jahan addresses community groups from across Birmingham at a peace rally in Summerfield Park.

Shortly after their deaths, Jahan called for calm. He was hailed as a hero, praised for bringing peace to a city that – according to Jahan's friend Atif Iqbal – was on the brink of a race riot.

"There was a lot of tension here," Iqbal told BuzzFeed News.

"You know, all the Asians, Muslims, Sikhs – there were rumours that they were going to fight the black community here." He credits Jahan's intervention to call for peace and harmony among Birmingham's ethnic and religious communities with helping to end the two days of violence.

Despite this, Jahan says the families have not been granted the "freedom to move on" by the British justice system, which he believes has "failed the boys".

Although the eight men in the car were charged with murder, the trial was riddled with controversy.

After two months of receiving evidence, the trial came to a halt after it was revealed that officers in West Midlands police, including detective inspector Khalid Kiyani, had been offering immunity deals to witnesses in exchange for their testimony, without the court's prior knowledge.

Meanwhile, the senior investigating officer, chief inspector Anthony Tagg, was accused of lying under oath, resulting in the Independent Police Complaints Commission (IPCC) – the UK's official police watchdog – claiming officers would have a "case to answer for".

The IPCC later concluded that no officer would be disciplined for the mishandling. Tagg was found not guilty of deceiving the courts, while Kiyani could not be prosecuted following his resignation from the police force months earlier.

Eventually, all eight suspects were cleared of three counts of murder, with the trial judge, Mr Justice Flaux, arguing that none of the men had any "intent to kill" – a statement that still shocks Jahan to this day.

Since then, Jahan says that the families have received little support from the authorities. Instead, he says, they've "relied on the support and goodwill of the public" to get by.

As a result, the families now want the Home Office to independently investigate the deaths of their sons – as well as the failures that followed in the court case.

"We put all our faith in the system," Jahan says, "and I believed it would prevail and we would get justice. But it went the opposite way.

"We had a trial, I sat in that court for three months watching the video of my son being murdered – and then to hear the verdict on the last day of 'not guilty' was such a shock. I had no words."

The trial's outcome has also had an impact on the health of the families. Sumera Ali, the younger sister of Shahzad and Abdul, says the verdict caused her father's "spirit to be broken".

"He'll have one meal a day, and suffers from bad depression," she says. "My mum tries to keep busy, but when she's alone, she's always thinking about them. So the fact that no one's been sent down ... It's caused a lot of anxiety, and a lot of stress."

Sumera adds that the deaths of her brothers left "a hole in our lives", particularly for her young daughter and nephew – Shahzad's son – who hadn't been born at the time of the killings.

Meanwhile, reminders of that night are ever present, especially when she sees one of the suspects in public.

"We've seen them out in the local supermarket, buying a bottle of wine, or a top. It makes you angry that they're carrying on their lives – but we lost our lives. We lost our lives ever since 2011."

It's a sentiment particularly felt by Musavir's mother, Rukaya Begum, who immediately breaks down into tears when asked about her sons.

In Urdu, she tells BuzzFeed News: "Living in this house has been very difficult since that night. And the the result of the trial, it made me feel like I was the criminal.

"No justice has been served. It feels like I'm living and dying every single day."

The families believe that launching the petition is their "last chance" to seek justice for their sons.

The petition, which has been backed by a number of Birmingham's community leaders and politicians, has been launched in a final attempt to "get to the bottom of what happened, that night, and the investigation that followed".

And while Jahan is positive about the campaign's impact reservedly, he admits uncertainty over what will happen if the future government decline the request.

"You look at people in a similar situation to me, like Doreen Lawrence. She fought for justice for 19 years … To be honest, I don't believe I have that much time."

In spite of this, he hopes that this effort "will prevail, with the support of the public", adding that he "owes them everything".

He looks up and smiles, reassured that even if "the boys don't get justice here, they will in the akhirah [afterlife]".

"They died protecting their communities," he says. "To me, that means they're shaheed [martyrs] – they died representing their religion. And that's all a father could want."