I sat in the car with my father one afternoon while Ron Isley sang a sweet lullaby to the both of us: "Oh, when will there be a harvest for the world."

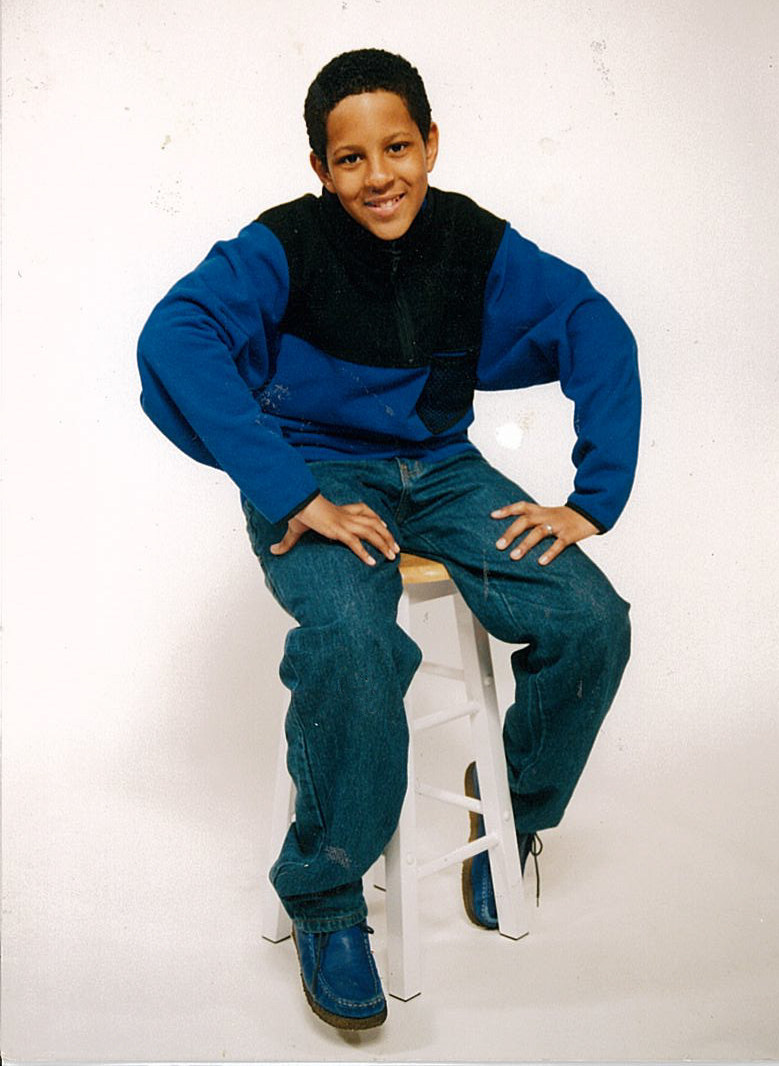

I was 16 years old, and I had just told my father that I was gay.

Ten years later, I made my music debut as Mykki Blanco, one of the first openly gay rappers to perform and dress in drag. My sexuality has always played a part in how people view my image, but luckily not my music. In 2012, when I released my first single titled "Join My Militia (Nas Gave Me a Perm)" (followed by songs that would go on to be viral hits that year like "Wavvy," "Haze.Boogie.Life," and "Kingpinning") the music industry and rap community was not as kind or as open as it is now, and I experienced lots of homophobia when I first took center stage. One can argue that the rap community is still rampantly homophobic; it is, after all, a boys club where women themselves have to fight for acceptance...so you can imagine where a gay man falls on the hip-hop food chain.

While I've always loved hip-hop, my success has come from my own visibility and building an organic international fanbase of people who were ready and waiting for a performer like me to come along. Discussions about transgender acceptance and rights were not in the popular media then, and this was just three years ago. Being a rapper whose live performance is like a hardcore punk show, but who is also a drag queen, is something many people viewed as too far out ever to succeed. Luckily for me, I've always understood my own inner power, my originality, and how to market myself in a very patriarchal entertainment industry. I believe that progressives want homophobia to change in the African-American community the way that homophobia transformed in white America. Culturally, I've never believed the experiences would mimic each other. I've also never agreed with the stereotype that the African-American community is more homophobic than any other group in the USA. As sisters and brothers of the diaspora, I've many times seen heterosexual and homosexual people lift each other up, but I've too often also seen the effects of misunderstandings that result in tearing each other down.

My sister — who's 13 years older than me — didn't take my being gay well at all. In fact, she blamed my mom for nurturing my gayness. She was furious at my mom and accused her of being too accepting of it. My sister told my mother that she should arrange for me to have sex with a woman so that I could have that experience; she genuinely believed that doing so would change my sexual orientation. Like most siblings, my sister and I would sometimes argue, and after learning that I was gay, when she got really angry, she'd call me a faggot. Every time she'd say it, it would really hurt. But a short time afterwards, she'd apologize and tell me that she loved me anyway.

When coming out to family, you have to be ready to accept whatever reaction they have. Hopefully you'll discover, like me, that your family's love is unconditional and unchanged by your sexual orientation. Unfortunately, it's the rest of the world that's not as accepting.

Homophobia in hip-hop will only transform in a fashion that's befitting of black culture. Dating back to the birth of blues and rock 'n' roll, when those genres were predominantly African-American, everyone always knew in hushed tones that certain celebrities of the time were flamboyant and eccentric, bisexual and queer, from the 1930s into the 1950s. These eccentricities didn't necessarily make those performers gay in the public eye at all, but in their theatricality, they were ahead of their time; because of their talent, people overlooked what could be considered today an outward aesthetic of queerness.

In African-American culture, the many talents of my people have always been a symbol of pride. Dance, theater, and the literal creation of musical genres all have their roots in black culture. African-American culture has always had an ideology of support, of taking care of its people and its community amongst a backdrop of white supremacy and oppression.

Transforming homophobia in the hip-hop community is going to come from public figures and pastors telling their communities to love their children and to embrace their sisters and brothers.

When I came out to my father, I was a ball of nerves, and the anxiety seemed unbearable; it was, at that time, the hardest thing I had ever done. And while sensing that his reaction would be one of acceptance, I certainly didn't expect an answer that revealed he had secretly known something about me my entire life that I, only a year or two before, had just come to realize. This explained a few things about my father's character and showed me just how understanding and loving a parent can be when faced with the somewhat taboo fact that they indeed have a gay child.

When I was 6 years old, he bought me a book on fairies because I had asked for it, and he didn't question why I wanted it. A few weeks later, in another toy store in another aisle targeted to girls, I found a "Build Your Own Fairy House" building kit. It was the equivalent of a very flamboyant bird house with glittery lavender and soft baby blue pillars with carnation pink ribbons and tiny plastic flowers sprouting everywhere. It was going to bring so many fairies to my room at night; I was overjoyed. My father said, "You're my son. It's not my job to judge you; it's my job to love you." Then he told me, "Michael, you may not have known them, but over the course of my life, I've had gay friends. Being gay makes you no different than anyone else who loves another human being." Those were my father's words to me that afternoon on our drive to the grocery store, and I knew immediately how blessed I was to have such an understanding parent. I knew the overall unquestionable acceptance was rare, especially being a young black boy living in the South.

My mother didn't get the luxury of a full-out honest admission. My mother and I shared a computer that was housed in my bedroom. She logged on one day to find an internet search history filled with searches that included "how to come out," "bisexual or gay," and "hot gay guys." Shocked, she summoned me to my bedroom. I had no idea what she wanted, but when I got there, I saw the "hot gay guys" web page open on the monitor. She looked up at me and asked if I had been on that website. I hesitantly said "yes." Then she said, "Do you have something to tell me?" and I said, "Yes, I'm gay." She turned the computer off and walked into her bedroom; she was getting ready for work and continued to put on her shoes. She looked up at me and said, "Well, whether you're gay or straight, you better not be out there being promiscuous."

Although my mother was loving and supportive, there was a strong element of surprise in her initial reaction. The next day, she again brought up that I was gay. She admitted that the day before, after I told her the news, she was so shocked by my revelation that she had called my best friend's mother to tell her that I was gay and to get some feedback on how to address my gayness. However, my mom was even more shocked when she learned that my best friend's mother and all of the other parents knew that I was gay for some time. My mother told me that she has known many gay people — men and women — and what concerned her most was how other people would treat me; she said she didn't want me harassed, bullied, or discriminated against for being gay. "I don't know why I didn't know, I've just always viewed you as being creative," she said. "I never thought once that it was an indication that you were gay. The most important thing is that you have self-respect; I don't care if they're women or if they're men — respect yourself in your relationships."

In retrospect, my parents treated me tenderly and respectfully when I came out to them; I was one of the lucky ones. I never had to come out to my friends, as my sexuality was never hidden. To be honest, you'd practically have to be from outer space not to know that I'm gay, although I never said that to my mother.

I've always had much pride in being homosexual.

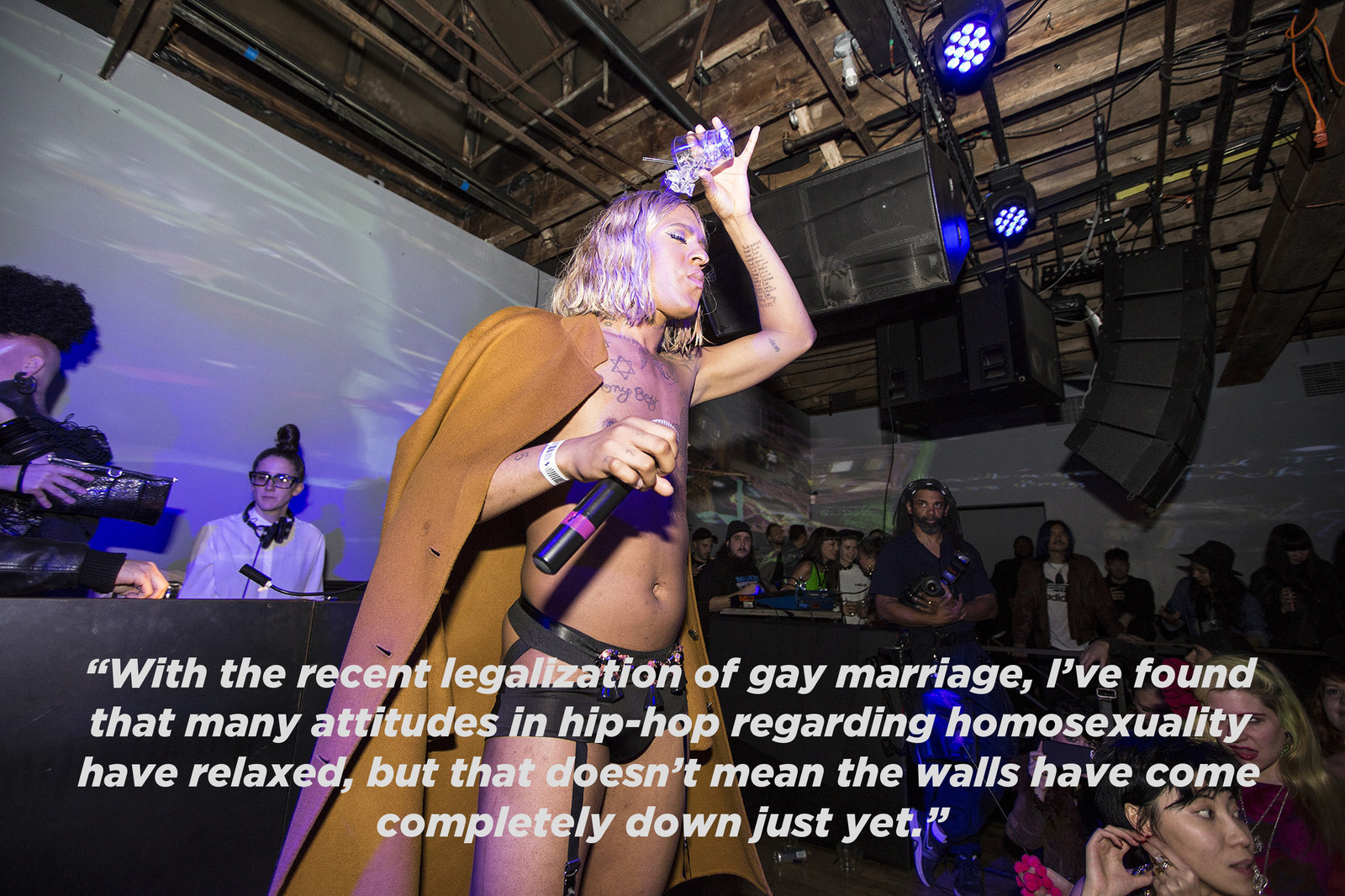

With the recent legalization of gay marriage, I've found that many attitudes in hip-hop regarding homosexuality have relaxed, but that doesn't mean the walls have come completely down just yet. The idea of an openly lesbian or gay entertainer in hip-hop still makes many uncomfortable. We have to formulate a message and truly embody what it means to say that you can be gay and it doesn't make you any less of a strong black man or woman. Discrimination, segregation, white supremacy, police brutality, and general racism have caused black people to feel that they have to be strong, but the hip-hop definition of strong is associated with a kick-your-ass, step-on-your-neck mentality or a conscious, self-righteous display of masculine power. The unfortunate psychological conditioning of both the hip-hop community and of patriarchal society globally is that most people are taught that strength only comes from masculinity. Homosexuality is viewed by many to be the opposite of masculinity, the opposite of what many feel is needed to survive in America. That's an attitude that will only change when society and the hip-hop community begin to lift up our sisters and truthfully see women and femininity as powerful and strong. When women are truly respected for their inner strength and not just seen as sexual forces, this will change. When femininity is seen as a source of power in hip-hop culture, homophobia will have less of a chance of surviving as an industry in a rapidly changing society.

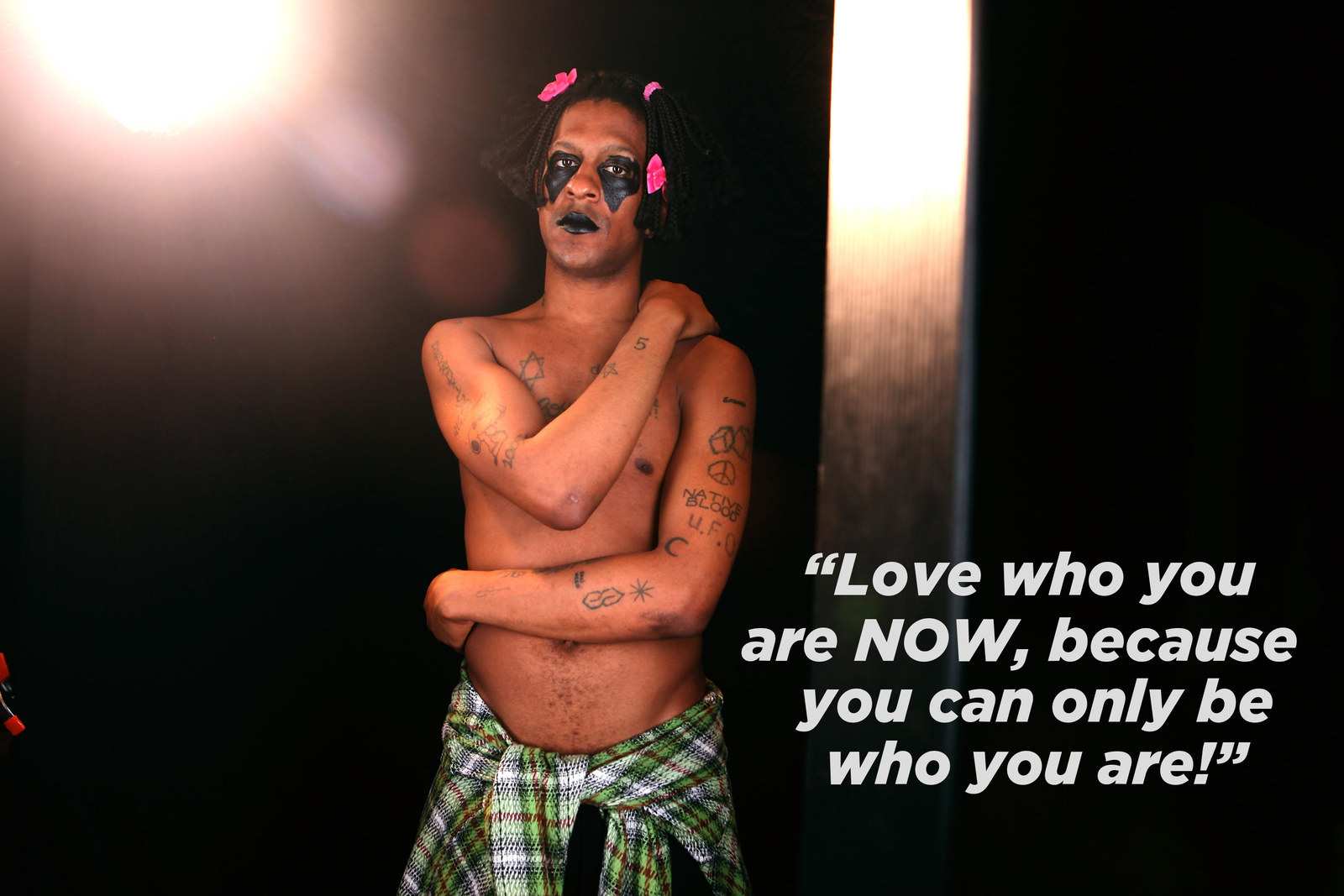

The advice I give to emerging lesbian and gay artists about coming out in the music industry is to follow your heart and be true to who you are. When you don't acknowledge your sexual orientation for fear of being rejected, you create a consciousness of deception within yourself. You will likely feel dishonest and "less than" because you know that you're not being totally truthful. People will likely find you less approachable because you've subconsciously created a protective wall around yourself so that your secret won't become known. Unfortunately, all these things will only hurt your professional and personal relationships, your creative process, and your career. Remember: A house divided against itself cannot stand; you cannot live a lie forever. So love who you are NOW, because you can only be who you are!