As his snowmobile slid to a stop on the vast ice off the coast of Labrador, 14-year-old Burton Winters must have wondered whether he would be rescued.

But by the time he had taken his final step in a 19-kilometre trek across the frozen sea, no one had come.

Winters' body was found Feb. 1, 2012, three days after he was first reported missing.

All three of Canada's search and rescue planes in the area were down for maintenance when he went missing. It took two days for the military to dispatch a helicopter to look for him, as most of those aircraft were initially unavailable, too.

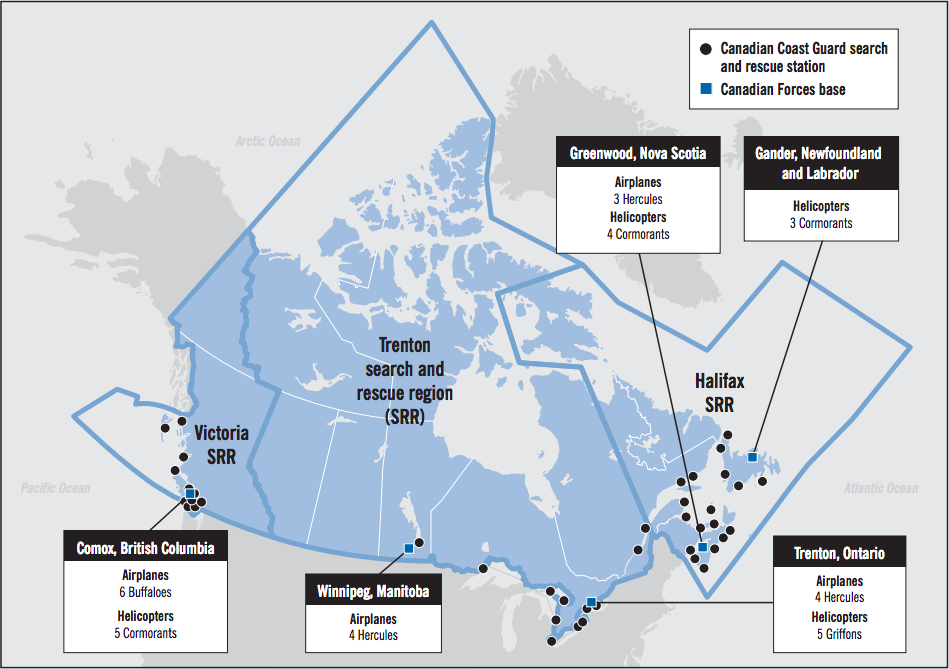

Every year, Canadian military aircraft respond to more than 1,000 search and rescue assignments. Approximately 140 highly trained search and rescue technicians save about 1,200 lives annually, according to the Department of National Defence.

But it's a task that is becoming increasingly complex due to Canada's aging equipment.

A BuzzFeed Canada investigation has found that Canada’s search and rescue planes are beleaguered by a disproportionate number of mechanical problems. The federal government’s failure to replace them threatens to erode the military’s ability to save lives at home, experts say.

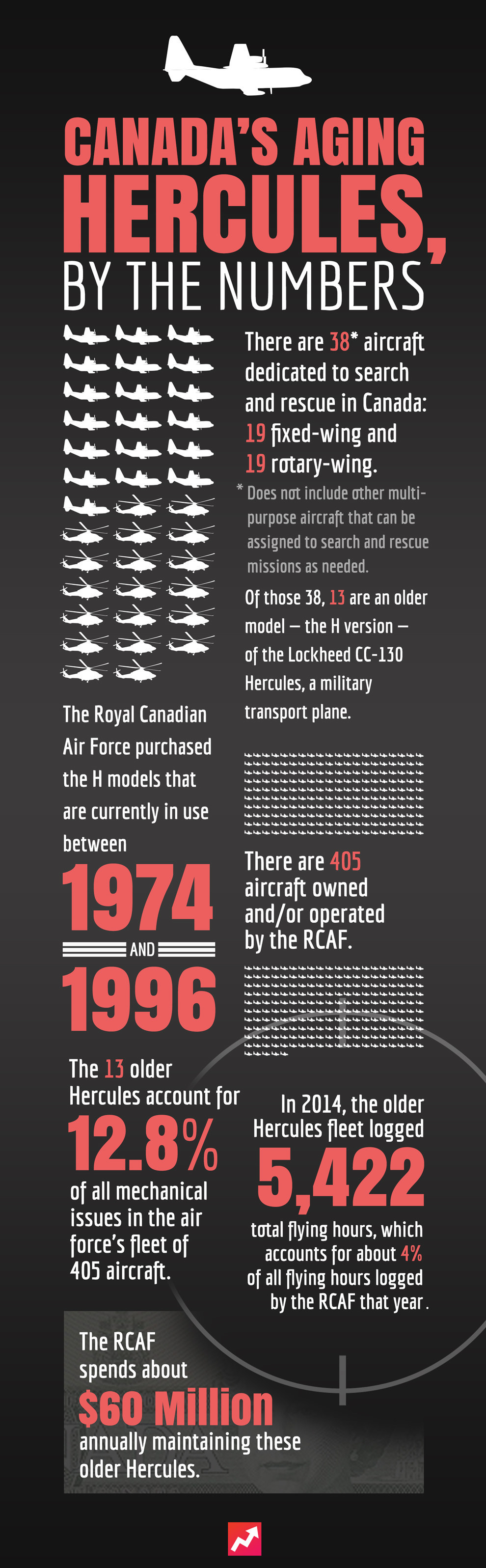

The Canadian military uses an older version of the Lockheed CC-130 Hercules aircraft to locate people in distress. It has been slotted for replacement for more than a decade. An analysis of air force data shows the aging Hercules fleet was nearly three times more likely than other military aircraft to experience mechanical problems.

The 13 H-model Hercules operated by the Canadian Forces accounted for about 4% of all flying hours logged by the Royal Canadian Air Force last year, yet were responsible for nearly 13% of all mechanical issues. The air force owns and operates a total of 405 aircraft.

The Department of National Defence spends $60 million annually to repair the 13 Hercules planes, but when contacted, the department would not say how many incidents involve those aircraft each year.

However, partial figures can be gleaned from a civil aviation database managed by Transport Canada. The database records incidents during which military aircraft come into contact with civil aviation authorities.

Though incomplete, the data suggests the Hercules has a higher rate of mechanics-related incidents than any other military aircraft. DND says this is not the case, but would not provide BuzzFeed Canada with Hercules-specific figures, or say which aircraft has the highest rate of incidents.

Ten years ago, the chief of defence staff said the Hercules fleet was teetering toward total dysfunction. Since then, the aircraft’s flying hours have dropped significantly, while individual reports in the civil aviation database detail emergency landings caused by issues ranging from engine shutdowns to smoking brakes.

DND said it would not comment on Transport Canada’s data. Officials said the Hercules “has proven worldwide to be a very reliable and safe aircraft.”

But defence experts say it’s natural for the aging H-models, purchased between 1974 and 1996, to experience more mechanical problems.

“What you can infer is that if 13 of 400 aircraft account for almost 13% of mechanical issues, that's clearly well above average and what we'd expect,” says Christian Leuprecht, associate professor of political science at the Royal Military College of Canada and Queen's University.

He said it doesn’t necessarily mean crews’ lives are at risk, citing the military’s “exceptionally good safety record.” The air force has strict safety protocols, pilots are trained to deal with problems in-flight, and DND this year reported a reduction in the rates of air and ground accidents.

“Someone’s life might be lost”

Alan Williams, the former assistant deputy minister of materiel at DND, says having search and rescue aircraft in the shop too frequently could have tragic effects.

Williams, who oversaw all military procurement until 2005, emphasized that more repairs don’t necessarily signal increased danger.

It does mean, however, that the Hercules — which make up about one third of Canada’s search and rescue aircraft — are available less often to respond to emergencies. Their age also means they can’t be fitted with technologies that would make them more effective, he said.

“At some point in time, because of a lack of capability, someone’s life might be lost,” Williams said.

A 2013 report by the auditor general found that the Hercules lacked modernized “sensors and data management systems,” and that the aircraft were being kept grounded longer because of a parts shortage.

“Two aircraft are in extensive maintenance at any time,” the report said, concluding that DND doesn’t “have enough suitable search and rescue aircraft.”

Michael Byers, a military expert at the University of British Columbia, argues the Hercules’ “notorious” mechanical problems have already had tragic effects. “They’re more often broken down than they’re able to fly,” he said.

The case of the Inuit boy who died off the coast of Labrador is a "stark" illustration of that, Byers said.

“Burton Winters...would quite possibly have been saved except for the mechanical problems that are plaguing the Hercules fleet.”

“It’s been a disaster since day one”

The Hercules, along with the Buffalo planes used on the west coast, have been slotted for replacement since 2004. The Liberal government announced that year it would spend $1.4 billion upgrading Canada’s fixed-wing search and rescue aircraft.

In 2005, then-chief of defence staff Gen. Rick Hillier said the Hercules fleet, which included the since-retired older E model, was “rapidly going downhill.”

''In three years and a little bit more than that, the fleet starts to become almost completely inoperational,” he said.

Hillier later compared the aging Hercules to a 1981 Ford Taurus. "You put it in the garage, it's automatically going to be $500 just to drive it in the door. That doesn't mean it's not going to break down as soon as you take it out.”

More than a decade later, delivery of the new aircraft is still years away. Byers blames “decades of incompetence.”

“It’s been a disaster from day one,” he said.

The Conservative government re-launched the search and rescue procurement after taking office in 2006, calling it a “top priority.” It’s been plagued with delays, however, partially due to accusations the air force initially rigged the competition toward one aircraft. The government issued a request for proposals in March.

Williams said procurement under the Conservatives has been “debacle after debacle.”

“All these projects start and then stop because they’re not properly planned and structured,” he said.

NDP defence critic Jack Harris says the Hercules’ “disturbing level of malfunction issues” is a result of the government’s failure to close the deal on the purchase of replacements.

“The consequence of not fulfilling their procurement role [is] not simply the fact of delays or higher costs, they are actually increasing the danger to our airmen and women and incidentally, as well, the public.”

An interactive map showing incidents involving the CC-130 Hercules, as reported to Transport Canada between Jan. 1, 2014 and today.

“It’s a matter of mission success”

Incident reports in the civil aviation database offer vignettes of search and rescue personnel forced to adapt to a complex military aircraft increasingly prone to problems due to its age.

Less than one month ago, emergency crews responded to a Hercules with overheated, smoking brakes at an airport in Abbotsford, B.C.

Twice on the same day in April, a Hercules flying to Trenton, Ont. declared an emergency and returned to Winnipeg due to an engine shutdown. In at least one case, airport rescue and firefighting crews were on standby, but both flights landed safely. Similar engine failures and flight diversions have previously occurred.

In July 2013, rescue and firefighting teams in Moncton, N.B. responded to a just-landed Hercules that had reported smoke in the cockpit.

“It’s a matter of mission success,” says Leuprecht, a defence expert at the Royal Military College and Queen’s University. “Many of these missions are missions where failure is really not an option. When you’re on a search and rescue mission, failure of your airframe means that whoever’s life is in danger that triggered the mission to begin with, that that airframe is now not available to complete that mission.”

Meanwhile, the Hercules’ flying hours have dropped significantly over the past decade, from 15,839 in 2005 to 5,422 in 2014. A portion of that drop can be attributed to the arrival of the new C-130Js — not used for search and rescue — which logged 5,426 hours last year.

Leuprecht says the remaining difference, a drop in nearly 5,000 hours, is more likely attributable to the military’s “particularly challenging” recent fiscal restraints than to lengthy repairs. Like other departments, national defence made deep cuts so the government could balance the books by 2015.

For Byers, the way ahead isn’t replacing the aging Hercules and Buffalo aircraft with more fixed-wing aircraft. He argues that the current technique of dropping rescuers from the back of military planes, then extracting them with helicopters, is World War Two-era thinking.

The flaws in Canada’s model were underlined in 2011, when Sgt. Janick Gilbert died in the freezing waters off Igloolik, Nunavut, while trying to save two Inuit hunters. He became separated from his team after parachuting from a Hercules, the Toronto Star reported. Because of an aircraft shortage, Gilbert and the other rescuers were left in the icy water to fend for themselves for hours.

“We do not have enough helicopters to provide the rescue function and we don’t have functional, reliable fixed-wing aircraft to find us,” Byers says. “And the end consequence of this is that Canadian search and rescue is at a developing country level, whereas our allies, like the United States and Britain, have moved on — many decades ago — and provide a service that is lightyears ahead of Canada.”

“It is embarrassing and it’s dangerous.”