There's a lot that may have seemed incongruous about the scene in a recording studio inside the songwriter Diane Warren's Hollywood office on a recent rainy afternoon, where the rapper Big Sean was holed up in a booth recording vocals for a new track. Warren is best known for big, dramatic power ballads from the '80s and '90s like Toni Braxton's "Un-Break My Heart," Aerosmith's "I Don't Want to Miss a Thing," and Cher's "If I Could Turn Back Time." Hers are songs that remind you of the glory and pain of love, whereas Sean's take on past relationships is perhaps best summed up by a line from his hit "I Don't Fuck With You": "Bitch, I don't give a fuck about you or anything that you do."

But there he was, singing — crooning, almost — on a track called "Am I Missing Something?" a sweet, down-tempo R&B ballad about a party guy realizing that he's lonely, that maybe what he's really missing is love. And when Warren's team of engineers and producers played it back for him, he liked what he heard.

"It's crazy," he said, shaking his head. "It's good. It's so tight."

"It sounds fucking great, man," said Warren. They high-fived. Warren and Sean met in December, when they both participated in a pre-Grammys Billboard magazine roundtable. Warren is nominated for a Grammy for Best Song for Visual Media for a song she wrote with Lady Gaga, "Til It Happens to You," which is featured in the campus rape documentary The Hunting Ground; "Til It Happens to You" has also been nominated for an Academy Award for Best Original Song. Big Sean is up for a Grammy for Best Rap/Sung Collaboration for "One Man Can Change the World," which he recorded with Kanye West and John Legend.

"I was like, 'Oh shit, Diane Warren!'"

"I was like, 'Oh shit, Diane Warren!'" Sean said. At the roundtable, Warren had asked him if he sang, and when he said yes, she told him she had a song for him. Warren has written thousands of songs, but with her near-perfect recall of everything she's ever written, she immediately knew which of her songs would be perfect for Sean to record. ("I think I have, like, a sixth sense. I'm like the song whisperer.")

If it hadn't been for the song with Gaga, Warren wouldn't have been nominated for a Grammy, and if she hadn't been nominated for a Grammy, she wouldn't have been at the roundtable and met Big Sean. And if it hadn't been for a documentary about campus rape that needed a song, Warren wouldn't have been nominated for an Oscar, and she also wouldn't have been getting recognition for a kind of song — powerfully topical, culturally relevant — that she's rarely done before. It's been years since Warren, who is 59, has had the kind of influence she did in the '80s and '90s, when most of the gold and platinum records that line the hallway of the office of Realsongs, the music publishing company she started in 1985, were recorded.

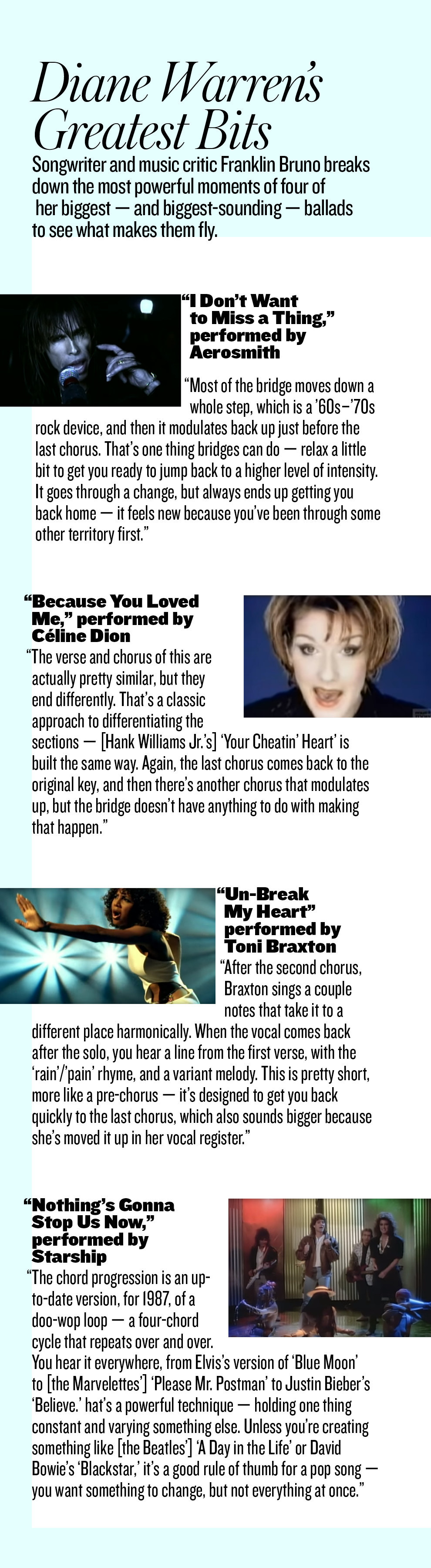

In her heyday, "Diane Warren song" became shorthand for a very specific type of big, dramatic power ballad, the kind you might want to hear at your prom or your wedding, or to belt out in front of strangers at a karaoke bar — but not one that's necessarily culturally significant. And so, in this light, recording with Big Sean and being up for an Academy Award — an honor, much to her chagrin, that she's never won — for a song written for a campus rape documentary (and not, say, the movie Pearl Harbor) actually aren't that surprising. Because if Warren's career were one of her songs, she'd be in the bridge right now, the section that emphasizes the contrast between the verses and choruses, and which brings us back to the huge chorus at the end. "I'm so into the next," she said.

Sean went back in the booth to work on the end of the song, where he was freestyling a verse. "Someone like him is authentic," said Warren. "I just had a feeling." But as she listened to Sean sing his freestyled verse, Warren was getting agitated.

She turned to me and said, "He's rhyming 'much' with 'much.'" Sean did another take. "He shouldn't rhyme 'much' with 'much,'" she said under her breath. She finally blurted out, loud enough for her engineers to hear, "He's rhyming 'much' with 'much.'"

"He's still working it out," said A.C. Burrell, one of Warren's producers, as Sean started on another take from the booth, where he couldn't hear the discussion in the studio.

"Oh, OK," said Warren. She laughed nervously. "I'm, like, trying to teach him how to rap. Ha-ha-ha." She was quiet for a second, but when the "much/much" rhyme came up again, she couldn't help herself. "Maybe 'enough'? Suggest 'enough' for the second line. Tell him 'enough.'"

"Just wait," said Burrell, who has a warm British accent. He had had a baby daughter six days earlier and was operating on little sleep, but never raised his voice. "Let him figure it out."

Sean did it again, tripping over the line with the second "much."

"OK, tell him," said Burrell, turning on the studio mic.

"Try 'enough,'" Warren said loudly.

"Where?" said Sean.

"In the line where you repeat 'much'…'enough' makes more sense."

"Oh yeah yeah yeah. You're right."

"I teach rap on the side," Warren said. Everyone chuckled. Sean did the verse again.

"That's much better," said Sean's voice from the booth.

"Does he want to write that down?" asked Warren.

"Will you let the rapper rap?" said Warren's producer Kyle Townsend. Sean did the verse again, and this time, everyone in the room — Warren, Sean's friend and music video director Lawrence Lamont, his recording engineer Max Jaeger, Burrell and Warren's other three recording engineers/producers, Bahareh Batmang (who does A&R for Warren, and whom everyone calls Batman), and Warren's friend, actress Kathrine Narducci, who was in town from New York — nodded and grinned.

Sean emerged from the booth to applause. He seemed sheepishly surprised. "I thought you were gonna be out here like, 'Eh, it doesn't really need the verse.'" Everyone assured him that the verse sounded great.

"I never worked with someone where I didn't write the songs," said Sean. "It's different. It's cool."

"It's funny how things happen," said Warren.

A few weeks earlier, Warren was sitting on a stage in an auditorium in the New York Times Building in Midtown Manhattan with Lady Gaga and Hunting Ground director Kirby Dick and producer Amy Ziering, for a TimesTalk discussion about the film and the song. Warren, who wears her black hair short with spiky bangs coming down to her eyes, was wearing jeans, a black leather jacket, and sparkly sneakers; Gaga was in a flowy ivory dress and platform sandals, her platinum hair pulled back.

"Me and Diane wanted to open the door to any person that went through any type of experience, that it was OK to feel that way and that you don't have to maybe defend yourself so much," said Gaga. "Because until it happens to you, they don't know how it feels."

"Gaga's performance starts out vulnerable, and then you're getting pissed," said Warren. Warren had originally wanted the song to end on that same vulnerable note it started on, but Gaga wasn't having it. "You wanted to make it epic," said Warren.

"I'm going, no, I'm not going out like that," said Gaga. "I'm not going out on this sad note."

Hunting Ground music supervisor Bonnie Greenberg, who's known Warren for years, contacted her when Dick and Ziering were looking for a song for the closing credits of the movie. "She came to me, and I was like, oh, I've got to do this," Warren told me. "I don't overthink it. It's almost like my brain is like a computer. I remember sitting down and coming up with the chorus. And the power of 'til it happens to you, you don't know how it feels.' That was so powerful, because it's so simple. And then it was just like, when you're in that, you're going through that, it's like, fuck you, go fuck yourself. Shut up. There's a line in there that's my favorite line — it's 'until you walk where I walk it's just all talk.' It's the essence of that song. So don't fucking tell me it's gonna get better. Just don't tell me."

Warren was molested by a friend's father when she was 12 — something she didn't reveal publicly until she started talking about the song — and Gaga was raped by an ex-boyfriend when she was 19, which she discussed for the first time on The Howard Stern Show in December 2014. "It's really interesting hearing you talk and hearing the depth of understanding that the two of you have," Dick said at the TimesTalk. "We've never really worked with an artist who had this kind of deep understanding."

It wasn't a foregone conclusion that Gaga was going to record the song. "I knew she'd talked about her experience on Howard Stern, so it was out in the open," Warren said. She called Gaga and played her the song with Warren's vocals. "She was, like, crying. She was sobbing on the phone." Warren got on a plane to New York the next day, and they went into the studio. (In the last few weeks, Warren has been back in the studio with Gaga, working on songs for her new album. "We did a couple of really great songs," she said. "I can't wait ’til they're out.")

Even though it hasn't been released as a single by Gaga's label, Interscope, or pushed on radio (and has therefore failed to crack the Billboard Hot 100), the song has elevated Warren to a new level of cultural relevance. It's hard to imagine the New York Times convening a panel about Warren's song "Because You Loved Me" and the movie in which it was featured, Up Close and Personal. "Til It Happens to You" has also raised her visibility; usually content to stay behind the scenes, she's very much been the public face of this song, alongside Gaga. "I'm starting to get these messages on Twitter and Facebook, people I grew up with, going, 'I never told anybody this but your song gave me strength,'" she told me. "I got tons of them, from people I didn't know. I've had a lot of records that have done really well, but nothing like this."

"I think the song is like, you can't hold it back. It's totally viral."

Warren repeatedly expressed frustration with the way the song has been promoted — or rather, not been promoted. Almost all of the publicity the song has gotten has been completely organic. The video, directed by Twilight director Catherine Hardwicke, a longtime friend of Warren's, has more than 24 million views on YouTube, and perhaps unexpectedly for a song from a documentary about rape survivors, the track has become a dance hit. It reached No. 1 on the Billboard Dance/Club chart for the week of Jan. 23, thanks to around 30 remixes by DJs like Tracy Young and Ryan Carrozza — which were done completely independently of Gaga or Warren or Interscope — putting Gaga at the top of the charts for the first time since 2013. The song has also started making its way onto radio — but not because Interscope has been pushing it. "The label's not doing anything," Warren said. "I think the song is like, you can't hold it back. It's totally viral."

For Warren, though, the Oscar is the holy grail. On New Year's Eve, she tweeted: "2015, great to know U, 2016, can't wait to meet U!!! #fingerscrossed #Oscars #TilItHappensToYou #2016isgonnafuckingrock."

Our conversation turned to Melissa Leo's 2011 Oscars campaign, for which she took out her own ads asking voters to consider her. (Leo won.) "People gave her shit for that," said Warren. "Why can't you promote yourself? I try to do it in a funny way. I'm posting Gaga doing my song. What's wrong with that? It's a beautiful thing. I don't want it to be too blatant — but where is the line? You should be proud of your work. Why not be proud of your work?"

Last year, Warren was nominated for "Grateful," a Rita Ora song that was on the soundtrack for Beyond the Lights, which lost to John Legend and Common's "Glory" from the movie Selma. (Warren was also critical of the promotion for "Grateful," grumbling that Ora and her label did little to push the song.) Warren remembers being in the audience and watching Gaga perform a song from The Sound of Music. "And I was like, ohh, OK, next year. I see it in my mind, just her sitting at the piano with a string orchestra. No drums, nothing. Just stripped the fuck down."

The field is not without its rivalries and passions, especially around awards season. In January, after the Oscar nominations were announced, songwriter and producer Linda Perry — whose song "Hands of Love," performed by Miley Cyrus, from the movie Freeheld, was not nominated — ranted about Warren and Gaga's collaboration. In a series of now-deleted tweets, Perry alleged that Gaga's contribution to the song amounted to one line, that the only reason Warren wanted Gaga to record the song was because she knew it would get more publicity that way, and that the only reason Gaga wanted to record it was because she knew Warren would be nominated for an Oscar. (Gaga has never pretended to have contributed more than the line and some of the arrangement; in December she told the Los Angeles Times, "It was already kind of a finished piece when I came in to work on it with Diane.")

Warren responded on Twitter the next day and elected not to take the bait. A couple hours later, after deleting the tweets, Perry tweeted: "My sincere apologies. I made a mistake to comment. I wasn't in the room when the #TIHTY was being written. More importantly, I wish the focus to remain on the great importance of the song and the message of the film." (Neither Perry nor Warren responded to requests for comment about the incident.)

Warren has won pretty much every other award there is to get, but the lack of an Oscar seems to have become a kind of existential shortcoming, a reckoning of her career that few other people in the world are keeping track of. Even she couldn't quite articulate why she wants it so badly, beyond pointing out the evident slight. "Since I've lost seven times, it'd be cool," she said. "They only give out one Oscar for song every year and they give lots of Grammys. It's a cool thing, like when you're a kid, to get an Academy Award. It's not about awards — but it would be cool."

On the day the nominations were announced, Warren was excited and relieved — she hadn't slept much the past couple of days. "Today was so cool," she said. "A lot of songs get released and a lot of songs don't get nominated, and this one did." If she wins, I asked, what would be next for her? "To write more songs? To have more songs in movies? It's like, winning this stuff isn't what makes me do it, but it's fucking cool. It'd be fucking cool to win it. This is the coolest part. I've won one Grammy, and then if I have an Oscar — you know how they have an EGOT? I'd be an OG." She laughed. "I'm an OG, right? An Oscar and a Grammy."

Warren grew up the youngest of three girls in Van Nuys, California, one of the sprawling suburbs of Los Angeles that sprung up after World War II in the San Fernando Valley. Around age 7, she realized she wanted to be a songwriter when she noticed the credits on her sisters' albums; the first one she ever noticed was the 1962 Drifters song "Up on the Roof," written by Carole King and Gerry Goffin. "I was really interested in [credits] when I was little," she said. "It's weird. Like, why would I be? I wasn't musical or anything when I was a kid."

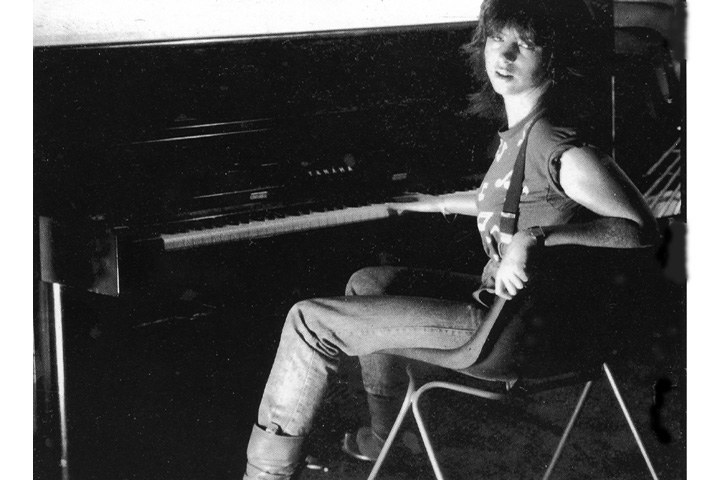

But by the time she was a teenager, she had started smoking pot and running away from home. On the wall in her studio is a newspaper cutout of an article about the missing 14-year-old Warren, with a picture of a sullen-faced girl with shoulder-length brown hair.

"I stayed with these bank robbers," she said offhandedly. "They were bank robbers and junkies. A friend of mine that I ran away with knew them, she said, 'We can stay here.' And they were shooting up heroin and shit. Like, I'm lucky I'm alive. They could have killed me. I was an innocent kid, you know? My friends would all think I was a bad influence, but I wasn't. It was them — they knew how to play the game more. I was more like a rebel." She went to juvie a couple times as a teen, sent there by her parents for smoking weed and skipping school.

Now Hardwicke is working on a movie about Warren's life called One Track Mind, whose logline is best summed up as "Troubled teen overcomes adversity to become one of the most successful songwriters of all time." The two met around 2009, at an Oscar party for the Quentin Tarantino film Inglourious Basterds. The first movie in the Twilight Saga, which Hardwicke directed, had come out the year before. "She comes up to me and says, 'I think I know you, man, you directed that movie,'" said Hardwicke. "She says, 'Listen, man, do you want to be my friend? I need some new friends. My friends are boring.'" (This is a common M.O. for Warren. When I asked her friend Kathrine Narducci, who was with us in the studio with Big Sean, how they'd met, she said Warren had approached her at a Coffee Bean because she recognized her from her role as Charmaine Bucco in The Sopranos.)

Warren went on to write two songs for Hardwicke's 2015 film Miss You Already. One day, when Hardwicke was at Warren's studio, she noticed the newspaper cutout on the wall. "I'm thinking, OK, wait a minute, you usually see an article of a girl missing for two weeks, that's the last you hear of that kid, probably. But this kid survived somehow and turned into this crazy outrageous prolific songwriter? How did this happen?"

Hardwicke became fascinated with her friend's life, flying one of Warren's childhood best friends to L.A. from Vegas and going on a tour of the Valley with her and another friend. "They told me two or three days' worth of stories, showed me scrapbooks. Her sister sent me her scrapbook. It's just the greatest underdog story. She was definitely ridiculed and sometimes bullied and laughed at by some family and friends for having this dream of being a songwriter."

By the time Warren was in high school, she'd been composing songs in her bedroom for a couple of years, but she had her eyes on a bigger prize: a $500 Martin 12-string guitar. Her dad, an insurance salesman, said he'd buy it for her if she raised her failing grades to nothing less than a B. "So one semester, A's and B's, I got that guitar," she said. "Next semester, D's and F's again. But I got the guitar. I still have it. It's a bitch to tune."

Hardwicke noted that this resourcefulness and tenaciousness has served Warren well. "People just said to her, like her mom and stuff, 'You're never gonna be successful, you're never gonna make any money doing this,'" said Hardwicke. "But Diane was so single-minded, she really believed that she could do it. She finds another way around the problem. If Kenneth Branagh didn't want to use her song in the Cinderella movie, then she gets her song on the Oprah Winfrey Network."

After graduating, Warren bounced around a few local colleges, taking mostly film classes and writing songs; her father had agreed to support her as long as she stayed in school. She eventually dropped out and tried selling her songs to producers in Los Angeles, to no avail, but finally got a job working for the singer Laura Branigan's producer Jack White (not the White Stripes frontman) as a songwriter. In 1983, White asked her to rewrite the lyrics of a French song called "Solitaire," which rose to No. 7 on the Billboard Hot 100.

By 1985, she had written DeBarge's monster hit "Rhythm of the Night" and also started Realsongs to maintain control over her music after suing Branigan's publisher for royalties. In the next few years, she had a string of hits, including Starship's 1987 song from Mannequin "Nothing's Gonna Stop Us Now," Chicago's 1988 songs "Look Away" and "I Don't Wanna Live Without Your Love" (which she co-wrote with Albert Hammond, father of the Strokes' guitarist), Michael Bolton's 1989 smash "How Can We Be Lovers" (co-written with Desmond Child and Bolton), Bad English's "When I See You Smile," and perhaps most notoriously, Milli Vanilli's "Blame It on the Rain." The duo won the Grammy for Best New Artist in 1990, but had to give up the award after the group confessed that they didn't actually sing their songs.

Warren said she wasn't aware they were lip-synching her song: "I didn't know. But I'd heard a rumor that in a concert the record stuck, or something like that. But other than that I didn't know. Whoever sang my song did it really cool. That's one of my favorite songs."

By the '90s, Warren was one of the most in-demand songwriters in the world, and by the end of the decade she'd work with huge hitmakers across a number of genres, including Celine Dion, Kenny G and Peabo Bryson, Mariah Carey, Cher, Monica, Brandy, Faith Hill and Tim McGraw, LeAnn Rimes, Exposé, Trisha Yearwood, Toni Braxton, Reba McEntire, Faith Evans, Taylor Dayne, En Vogue, Meat Loaf, Whitney Houston, and, of course, Aerosmith. A plaque affixed to a framed display of the gold discs and album covers of four of her biggest hits — "Un-Break My Heart," "How Do I Live," "Because You Loved Me," and "I Don't Want to Miss a Thing" — reads, "Presented to Diane Warren, career saviour of the '90s, in recognition of your global success. From all your friends at EMI Music Publishing." (In 1998, EMI distributed a limited-run six-CD career retrospective to people in the entertainment industry to showcase her ability to write songs for movies and TV.)

Those songs have found second and third lives on karaoke machines, as Warren herself discovered when she went to a party at screenwriter and Dawson's Creek creator Kevin Williamson's house. "He showed me, like, all these things — I have, like, my volumes of karaoke songs with my name on them. I think I ordered them once and I was like, oh my god, I have, like, my karaoke greatest hits. It's totally cool."

Her star dimmed somewhat in the 2000s, as the rap ballad and the slow jam replaced the power ballad, and the adult contemporary genre — which had ruled the airwaves in the late '80s and '90s — faded in popularity. Still, she adapted. She continued to write songs for soundtracks, which garnered her award nominations for her work on films ranging from Pearl Harbor to Justin Bieber: Never Say Never, the soundtrack for which she wrote the only new song. But much of her album work — for artists including Carrie Underwood, Rihanna, and Jennifer Hudson — didn't chart, or even get released as a single.

"I still love them," she said, referring to her songs that haven't been hits. "Sometimes it's frustrating when you know something could be a hit and it's not. There's a lot that goes into it. I could write a hit song, but it has to be done by the right person, it has to be promoted. There's a lot that's not in my control. I'm proud of my songs no matter what. They're all hits to me."

"It's frustrating when you know something could be a hit and it's not. There's a lot that's not in my control. They're all hits to me."

High-minded critics have not always been impressed. Writing about Braxton's "Un-Break My Heart," the notoriously picky former Village Voice music critic Robert Christgau called the song "a miraculous Diane Warren ballad," but couldn't help but add "the miracle being that it's by Diane Warren and you want to hear it again." Rolling Stone put "When I See You Smile" on a 2013 list of "20 Love Songs We Never Want to Hear Again," writing that "no blow-dried power ballad ever did it bigger, dumber, emptier or gloppier."

But Jody Rosen, critic-at-large for T: The New York Times Style Magazine, dismissed Warren's naysayers. "It's not easy to write songs like the kind she writes, and write songs that good," he said. "Of course she's a cheeseball — that's the tradition she's operating in. She made her name with power ballads. And not just power ballads, but power ballads to the nth degree. Just so relentlessly, unapologetically schlocky. That's what I like about her."

Warren attributes her success in part to her work ethic: From her home in the Hollywood Hills, she drives into the office in her blue Bentley six to seven days a week at 8:30 a.m. ("very un-musician-y hours") and often stays well into the evening. When I asked what she does outside of work, she had to think for a moment. "I have friends and stuff. We go out to dinner. I wish I did more. I'm such a workaholic," she said. "But I have more of a life than I used to. I used to have no life at all. I used to just work and go home, work, go home."

She sticks to a strict schedule of writing one song per week, often starting with a phrase that turns into the title — "I Don't Want Want to Miss a Thing," "Til It Happens to You" — and building a song around it. Warren doesn't read or write staff notation, but she records the melody onto a cassette (she can carry a tune, and plays piano and guitar) and listens back on one of around 10 Walkmans she owns. ("Cassettes are cool again, right? You hold on to something long enough and it becomes cool again.") She works on one song at a time because, she said, "I could be spending all day on one line. That can be a difference of making, in my mind, just making a great song or a good song. A little break, a little bridge, a little B section — it's all super important." Or as she tweeted recently: "One little chord can make such a huge fucking difference."

Then, with the help of a team of engineers and producers (one of whom, Mario Luccy, has been working for her for over two decades), she'll record herself singing the lyrics and play the track for the artist. It's an old-school process, but one that gives her more control over a track than the typical songwriter — and ensures that she usually is the sole songwriting credit on a track. "People come to me and say, 'Will you write the topline on this track?' Well, sorry, guys, the topline is the song. So if I'm going to write on your track and I'm going to split the song with 10 people and I really wrote what that song is — it's not my thing."

It is clear Warren does things her way — but it's possible that doing things her way also comes at a bit of a cost. She's not at all part of a crowd of songwriter/producers and performer/producers like Max Martin, Dr. Luke, Ryan Tedder, and Bonnie McKee, who write songs for huge pop stars like Britney Spears, Katy Perry, Taylor Swift, Kesha, and Adele; none of those artists except for Spears (2000's "When Your Eyes Say It") has released a song by Warren. The Max Martins of the world also seem happy, or at least willing, to share songwriting credit. (An extreme but not unrepresentative example: Rita Ora's 2012 song "How We Do (Party)," with 12 credited songwriters.) Contemporary songwriters have also embraced virtual collaboration — Jack Antonoff recently told Billboard that when he and Taylor Swift were writing her latest album, 1989, "half the time we worked on email. Like me in bed and her in bed, 2,000 miles away, sending stuff back and forth" — a process that is anathema to Warren.

I wondered if she ever feels like the last of a dying breed of pure songwriters, and she said, "Yeah. I always felt like this." Perhaps that's why she's fiercely protective of her songs, but also not precious about the actual work of writing songs. "I'm almost the 2016 version of the Brill Building," she said, referring to the famed New York office where songwriters like Carole King and Gerry Goffin, Ellie Greenwich and Jeff Barry, Barry Mann and Cynthia Weil, and Phil Spector churned out hit after hit from their cubicles. "Those were my heroes."

And for someone whose career was sparked in part by liner notes, she finds it depressing that in the age of streaming, the songwriter's role isn't as obvious. "I kind of miss CDs and all that. You want your credits there. You want people to see your name," she said. "But to find your name they have to go to all these sites to find it. It's stupid, it's fucked. I don't think it's fair. I love getting a CD and opening it up and seeing my name, or seeing other people, seeing, like, who did what."

Despite their visibility on liner notes, though, Brill Building songwriters tended to stay in the background, ceding public recognition and fame to the musicians who recorded their songs — and until recently, that was Warren's modus operandi as well. It's been only in the last few years that she's begun emerging into the public eye, perhaps because of the tendency of today's songwriters and producers to be more visible. To her own surprise, she's embraced it — she loves getting notes from fans, she loves engaging with people on Twitter, she loves going to Oscar parties.

But when I asked her if there were any emerging songwriters she was excited about, she was stumped. "I never know who to mention — probably somebody. I'm just, like, in my own world." She likewise doesn't consider herself a mentor to younger songwriters. "I'm too busy with my own stuff. First of all, I don't want to sit and listen to anybody's songs, because I'm always writing my own, and then I don't want to, like, judge someone else's songs, and I don't want someone else's songs sticking in my head because I'm trying to write my own. That being said, I stay in touch with the times. I'm always aware of everything going on — I work with a lot of young artists. So I keep current. And a lot of it is in the language. And a lot of that is keeping stuff edgy, which is fine for me, because I like being edgy. You know, not too sappy."

When I asked how she thinks she's perceived by other songwriters and producers, she paused for a moment, then said, "I have no idea. I hope I'm respected." Probably the more significant question, though, is whether she cares. "I don't lose sleep over it. There's a saying: 'What you think about me is none of my business.' Of course we all want to be liked and we all want to be respected for our work. But you can't sit and go, like, 'I'm worried about what you think of me.' I'm not. I'm not."

THE ESSENTIAL DIANE WARREN PLAYLIST

The eight-person Realsongs office takes up the entire eighth floor of an office building on Sunset Boulevard. In a sunny corner room kept pristine for visitors, there's a wooden coffee table in the shape of a cassette tape and windows with an unfettered view of Los Angeles all the way to downtown. Awards rest on top of the grand piano and practically every other surface.

The entire office is decorated in what can only be called '90s high kitsch, as though someone won the lottery and spent it all at a naughty gag gift shop. There's the glass with the spilled red wine, the wind-up penis toy, the stuffed pig with a huge pink penis and tuft of black pubic hair, macho Ken dolls in leather outfits with big penises sticking out of their pants, a cartoonish painting of a rooster that has the caption "PHOTO OF MY COCK" ("It's like the sick side of me"), desk signs with slogans like "I'll Be Nicer If You'll Be Smarter" and "Smile…… It will either warm their heart or piss them off….. either way you win!"

There's also a small gym where Warren works out alone or with her trainer; a game room with vintage arcade games including Frogger, Galaga, and Ms. Pac-Man, along with a Looney Tunes gumball machine; a room decorated like a '50s diner, with a curved counter, pleather stools, and an inlaid floor that says "D's Diner"; offices for her staff; and the small, darkened room where she writes, which is covered in mounds of cassettes and loose papers.

Warren's game room and reception desk, and some office decor.

If everything goes according to plan, though, she'll have to clean out that room soon: She's been in this office for 20 years, but she recently bought a building on nearby Cahuenga Boulevard, where she'll be moving Realsongs sometime later this year. She seemed alternately excited about the new building — Sean had driven by and noticed that the light-up sign with the Realsongs logo was already up on the exterior — and nervous about disrupting her process. "I'm comfortable here. Maybe I'll keep it," she said, referring to the current space. "I don't know."

The office is also inhabited by two parrots: Buttwings, a Senegal parrot whom Warren has had since 1993, and one she's taking care of that belongs to a friend. They're both ignored by Warren's cat, Mouse, who's more often found napping in her bed by the window. Mouse, a tiny, speckled Cornish rex, is another frequent subject of Warren's Twitter, where she makes the same kind of dirty, funny-ha-ha jokes that infuse the office. On a picture of her and Mouse: "Me and my pussy. And my cat! :O)" A picture of Mouse holding up a paw: "Raise your hand if U think there are too many stupid people."

Warren is a longtime animal rights activist who hasn't eaten meat in 16 years and says she's almost vegan, and doesn't allow her employees to eat meat in the office. Her nonprofit, the Diane Warren Foundation, donated nearly $1 million in 2014 to mostly animal-related causes. "I've been going to all these Oscar parties," she said, "and when I see people wearing fur I tell them how horrible it is. Sometimes it changes their minds." One time, a few years ago, she says she went to Barneys in Beverly Hills and "I put a bunch of gum all over the fur. I just always loved animals. I prefer them to people."

Every day is bring your pussy to work day! Sometimes I bring my cat too!

It's not unusual for an animal lover to be in a relationship with another human. And certainly, it's not incumbent upon Warren to be in a relationship for the sake of being in one. But most animal lovers and single people are not also among the most successful love song writers of all time. So it is almost ironic that not only has she never been married or had kids, but she also hasn't even been in a romantic relationship since the early '90s. It does seem like she's replaced whatever gratification she would have otherwise gotten from a romantic relationship with work and her pets. "I haven't really been in love the way most people are in love," she said. "I think I love my cat more than I could love any human." (An article in Out magazine referred to her as "lesbian songwriter Diane Warren," but when I asked her about it, Warren said, "I'm not a lesbian! It's weird, I'm not gay. Everybody thinks I am, and I wish I was, to be honest, because I have some great lesbian friends, and they'd be great girlfriends, but I'm not a lesbian.")

The songwriter and music critic Franklin Bruno, who's currently writing a book about song structure in popular music, said of Warren's lyrics, particularly the earlier ones, that "beyond sketching out a situation that could apply to many, many, many romantic partnerships — they're very general. There's very little specific narrative or specific imagery." Even a song like "Til It Happens to You" is not just about being sexually assaulted, Warren said. "'Til it happens to you — you're bullied at school, if you're suicidal, if you lost your job, if you lost a loved one, if you just got diagnosed with an illness, losing a child, losing your animal — you know what I mean? No one knows what it feels like."

Perhaps that's why, as Bruno pointed out, her songs are always written to appeal to the widest possible audience: "They're very general. There's very little specific narrative or specific imagery." She doesn't have that personal experience to draw from, and so she draws from everything.

As the afternoon turned into the evening, Warren and Sean were still working on the song in the studio. There was talk of ordering food — everyone ended up getting veggie chili — and once they were satisfied with "Am I Missing Something?" they decided to record a second song of Warren's. "I'm really good at [power ballads], but I do other stuff," Warren said as we listened to Sean sing a mid-tempo R&B jam called "Used to It," about a guy telling a girl she'd better get used to being treated well. Sean was also working on a rap verse in the middle of the song. "Right now, in 2016, it's much more interesting to be here with Big Sean than a singer I've worked with before," she said.

"You're so good," said Sean when he came out of the booth. "It's crazy."

In the second chorus, Warren had changed the word "touched" to "fucked," and when he came out of the booth, she asked if he wanted to say "fucked" in all the choruses.

"Nah, one time. One special time," he said, and smiled.

Warren left the room for a few minutes, and as her engineers played back the track, Sean glanced at Warren's wall of memorabilia — a hodgepodge of magazine and newspaper cutouts, fan letters from prisoners, '80s headshots of Warren — and noticed a page ripped from Star magazine with the title "Grande-Sized Ego," about the singer Ariana Grande. "Oh shit," said Sean, who broke up with Grande in April after dating for eight months — according to TMZ, because of his lyric about his "million-dollar chick with a billion-dollar pussy" in the song "Stay Down."

"She wasn't nice to us," said one of Warren's engineers. "We worked with her — that's why [Warren] put it up." (Warren recently tweeted a picture of Mouse on a table eating human food, writing "Yea so im spitting on their food, whatever, isnt this what that ariana chick did w that donut?")

When Warren came back, I asked if there's anyone she wouldn't work with again. "Probably," she said. "I'd have to think about it. But I always forgive and forget. Especially if they sell a lot of records."

Soon, it was time for photos. Warren and Sean took a few together, and then he sat next to Batmang to help him choose which to post on Instagram. Batmang showed him how to use the app Facetune to edit the images, and he finally decided on a photo of them both holding up their middle fingers to the camera, posting it to his Instagram with the caption "Me n my new best friend Diane Warren! #legendary." A few minutes later, Warren asked me to show her how to use her Instagram account, on which she had posted a grand total of three photos, the latest of which was one of her and Gaga from a party the night before. "I use Twitter, I had to have someone show me how to post this photo last night," she said. "How do I see the photo?" I showed her how to look up Big Sean on Instagram, and then where the photo of the two of them was. "Wow, he has so many likes already!" she said.

Warren kept monitoring Instagram and Twitter, where Sean had also posted the photo, marveling at the number of likes that were piling up. "Wow. Wow," she said. She scrolled through her mentions on Twitter. "His fans know who I am!" she said. She continued scrolling. "I've been around a long time. It doesn't feel that way. It feels like I'm just starting."

CORRECTION

Britney Spears recorded one song by Diane Warren. An earlier version of this story stated Spears had never recorded a song by Warren. (h/t @thebostonista)