It's just turned 9 am on a Wednesday morning and the Sydney CBD pavement is a whirl of high heels and suits as office workers rush to their desks in a seemingly never-ending parade played out every morning on the city streets.

A dark grey felt fedora peaks out above the swirling crowd, a plume of orange feathers affixed to the side seems almost electric against a backdrop of dull greys. Deng Adut, 32, slices through the crowd, swaggering toward the drab marble-columned Family Court of New South Wales. People around seem to magnetically undulate to the left and right of Deng as he pushes forward.

It's hard not to stare at Deng; his height, his handsome face and above all his fabulous sartorial style (all of his clothes are bespoke and made-to-measure by a tailor in the Blue Mountains) all make him stand out. Today it's a three-piece double-breasted light grey suit. All of these elements combined with his almost regal presence give you the feeling that you've stumbled upon a movie star casually strolling the streets while you're getting your morning latte.

Deng is a solicitor and today he's representing a client in a family law matter.

"It's a pretty messy case involving children," he says in a soft-yet-authoritative voice, adding that he, "wants it resolved and mediated today."

The very idea of Deng pacing an Australian courtroom in front of a magistrate in a white, horsehair wig while delivering dry legal arguments steeped in 19th century British etiquette is almost unfathomable when you consider that 22-years-ago, Deng was a skinny 10-year-old boy holding an AK-47, shooting to kill and killing to survive in the midst of the Sudanese civil war.

"Death becomes the norm for a young child, and you look at death like it’s nothing," he tells BuzzFeed News.

"Ten-year-olds don’t think about killing people, they think about eating and playing Nintendo games. Well my Nintendo games were with real guns. That’s your best friend, and you stop being a 10-year-old when you bear arms and all you've known in your entire life is how to survive, how to run away."

Deng grew up on the Nile River.

"My family raised cattle and dad would hunt food, including hippopotamus and crocodiles," he says. At six-years-old he was taken from the family property and forcibly conscripted into the Sudan People's Liberation Army (SPLA); then a rebel group and now the official military wing of South Sudan. He was marched into nearby Ethiopia and trained as a soldier. Following the massacre of over 2000 Dinka tribes people in the town of Bor in 1991, Deng was sent into the chaos of war just as a crippling famine started to take hold of the region.

Tortured and injured several times, he tried to commit suicide twice. "Death became the desirable outcome for me. There was just too much pain I was going through," he says.

"I cocked a gun to my head and pulled the trigger and it didn’t go off, the second attempt was with a hand grenade".

A bullet wound which almost killed Deng ultimately saved him. At 11-years-old he was running through a village when he was shot in the back, with the bullet lodging near his spine. While convalescing, Deng's brother found him and smuggled him to nearby Kenya where they lived in refugee camps before coming to Australia.

“In 1998 we were lucky and we got accepted to come to Australia on June 26, which I think is my very own Australia day,” he says.

Deng taught himself to read and write English as a 15-year-old and put himself through TAFE, which eventually lead to him studying law at the University of Western Sydney while living in his car.

Sitting today in his office at the law firm he's a partner of in Blacktown in Sydney's west, Deng tells BuzzFeed News he has a message for migrants who don't feel a part of Australian society.

"I never expected to be in this position today. I lived in Ethiopia as a refugee, I lived in Kenya as a refugee and came to Australia as a refugee and became a citizen, and all I know about South Sudan is war. I have been here [Australia] the longest time, 17 years in one place.”

"Other migrants here [in Australia] should look to the future. The people that call you names, let it go and ignore it. Those ones who cultivate on negative energy, I don't think they belong here. Negativity is un-Australian. Don't be like those who actually think we should not be here." `

Deng is one of many Sudanese migrants making the most of life Down Under.

Ajok Marial, 17, was spared the horrors of growing up in a war zone. Her family fled South Sudan when she was five-years-old. Ajok has little memory of her birth country.

Returning two years ago, she was shocked. "It was really crazy just to see so many homeless people and the reality was like, 'whoa'," she tells BuzzFeed News.

"I couldn't meet a lot of my family because South Sudan was at war at the time. When we came back [to Australia] the experience made me so humble and I changed my mindset at school and I really focused on achieving something in life because my parents sacrificed so much."

Fresh faced and wide-eyed, Ajok’s beauty is hypnotic. Standing at almost 6ft tall, she's walking to the small apartment in Guildford in Sydney's west where she lives with her mum in one of those omnipresent four-story brick buildings that populate much of the western suburbs.

"I wanna be a model," Ajok says as she walks up the driveway as if it were a Paris catwalk, demure and sleek, making her dowdy tartan school skirt and oversized navy blazer look like it's haute couture. But her modelling ambitions aren’t about glamour, for Ajok it's about showing that beauty comes in all colours in an often monoracial media landscape.

“It’s very important [to have diversity in modelling] because Australia is a very multicultural society, so it's good for them [children of refugees] to know that they are accepted in society.”

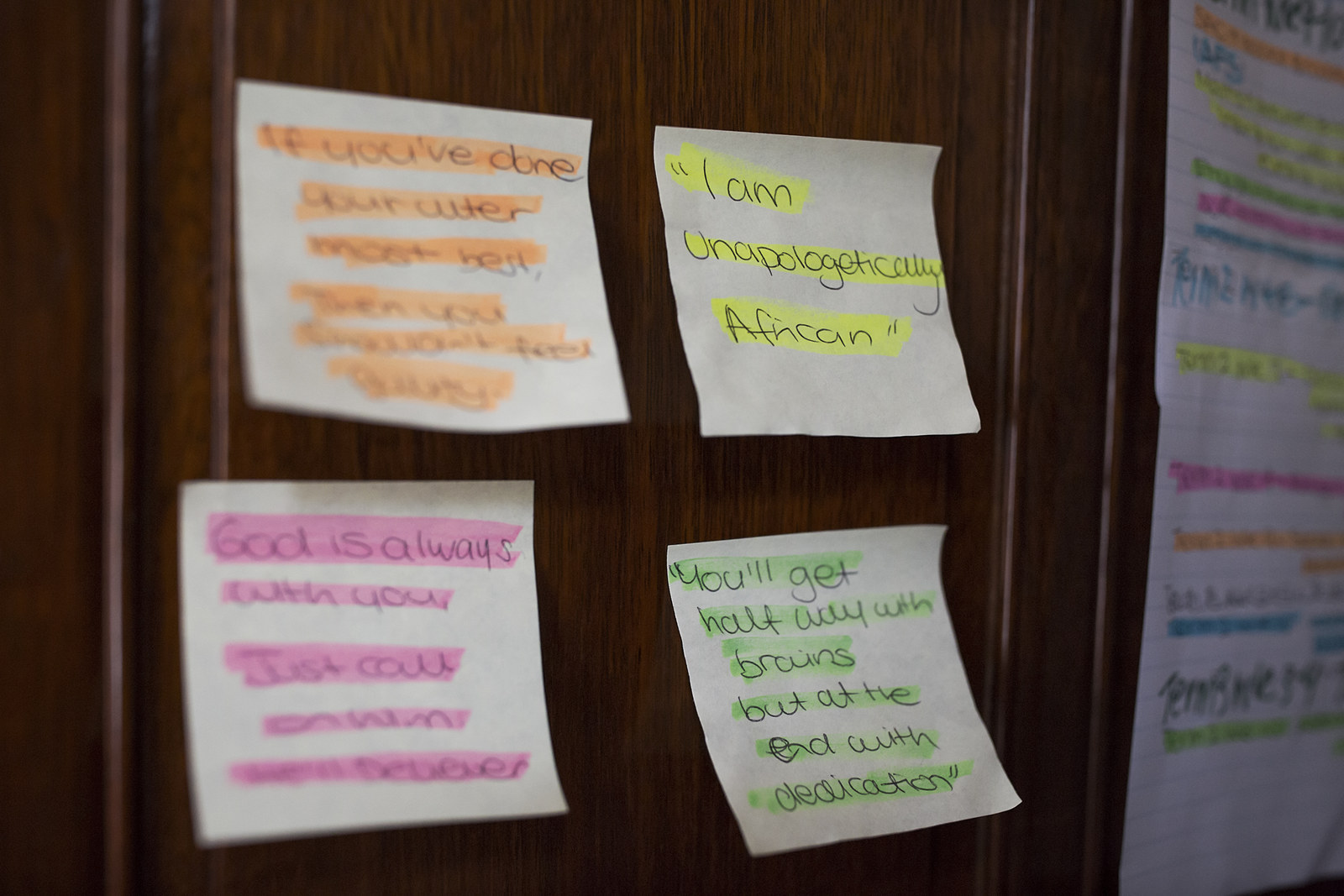

Far from being the stereotypical beauty queen, Ajok is also whip smart. “This is where I study,” she says, showing off the tiny makeshift desk squeezed between a large chestnut wardrobe and the wall of her parent’s bedroom. A cluster of fluorescent post-its is stuck on the wall, inspirational quotes scrawled across them in ink. One reads "I am unapologetically African". Ajok says the messages helped her get through HSC study sessions. She's hoping to study law and become a human rights lawyer.

"I see myself doing a lot of things. I‘m a very ambitious person and I’m optimistic, so maybe law or modelling. If one doesn’t work out I’ll do the other."

“I want to be an advocate for African Sudanese people. I envision myself actually being an entrepreneur in the future and opening a couple of businesses, and yeah, having some business overseas which would help people in South Sudan.”

The South Sudanese community is known to deal with its problems behind closed doors. Suicide, depression and the impact of racism, while a big problem in the community, are rarely discussed despite the best efforts of local leaders. Last year South Sudanese leaders marched on the streets of Auburn in the hopes of opening up the conversation around mental illness and depression. They were worried that young people, despite growing up in Australia, feel like they don't belong here due to racism.

In October, the brutal murder of 23-year-old Mount Druitt man Pabeek Gaak, known to all of his friends as Teddy, shocked the close-knit South Sudanese community. The 18-year-old charged with murdering Gaak is believed to be from the same community and will appear in court in December.

A known hard worker who sent money back to his impoverished family in South Sudan, a young woman at the makeshift memorial where Teddy was killed softly wept and asked, "How many more of our brothers have to die?".

While stories of tragedy amongst the South Sudanese community may be common, stories of triumph over the odds are also there for those who look. Case in point, 19-year-old Farous Ngath.

Now on the cusp of becoming an elite sportsperson, Farous vividly recalls her first few months in Australia as a confused seven-year-old.

"I remember coming to Australia from Egypt [where her family lived after fleeing South Sudan] and I just remember it being so different. I didn’t speak English. I didn’t know anyone and it was kind of difficult. My mum had to go to a job straight away and me and my brothers had to go to school. We didn’t even know the language."

Tying her finely braided hair behind her head, Farous begins to fiercely bounce, kick and flip a soccer ball against a backdrop of blooming purple Jacaranda trees. It's electric to watch. It's this soccer prowess that has gotten her noticed in the elite world of American college sports. Earlier this year Farous was offered a highly coveted soccer scholarship to attend Ohio State University in the United States, she will leave early next year.

"When I knew there was a scholarship I wrote up my CV and sent it out to a coach who sent it to another coach. I am really lucky," she says.

Sporting glory isn't the only marker of success for Farous, she has hopes of starting a school South Sudan, where less than 30% of children attend school and only 10% of schools are actually in a permanent building. Just 12% of South Sudanese women are literate.

"Success for me is winning a scholarship and being successful at sport, but real success is going back there and opening a school. I haven't been back since I was little, but education is what's needed there right now."

Inside the PCYC at Blacktown, the much-maligned suburb in Sydney's outer western suburbs, Laat, 21, is navigating his way through rows of teenage boys from a multitude of ethnic backgrounds. Intently they stare ahead with eyes fixed on their coach while dribbling basketballs, methodically switching their bouncing hands; left to right, right to left.

"Basketball was something I always loved. I always played after school with my brothers. I thought I might as well take this serious because I was good at it," Laat says.

That sporting prowess has seen Laat score a lucrative basketball scholarship to a junior college in the United States, and if his supporters' enthusiasm is anything to go by he could be the next Australian star in the NBA.

"Heaps of players try to go there and play, and it feels like I’m finally being noticed for all the hard work, getting that opportunity."

"I just want to experience college life and get a degree. If basketball doesn’t work out I have something to fall back on," Laat says as a group of mates swarm him with a flurry of elaborate handshakes and backslaps. Suddenly he's disappearing into the noise of basketball training engulfing the hall.

For so many, sport acts as a pathway to a better life. Still at the PCYC, basketball training is winding down. Acouth Acol, 31, is greeting everyone, asking about people's families. As the teenage boys begin to leave the venue he says, "I use to play basketball when I first came to Australia and we [other young refugees] could play Aussie guys, Filipino guys. You didn’t have to speak the each others' language, sport is a language everyone understands".

Acouth and his family fled Sudan's capital Khartoum for Egypt as a 16-year-old, where he worked seven days a week to support his family. "I worked right up until I left for Australia, the time I had off I went to church, saw family and friends," he says.

In 2002, he came to Sydney as an 18-year-old, and today Acouth is a highly respected man amongst the many diverse migrant communities in western Sydney, working with young people at the Community Migrant Resource Centre, a not-for-profit organisation that provides specialised support services to newly arrived migrants, refugees and humanitarian entrants.

"I hear different stories of newly arrived migrants every day and these refugees have been in the same shoes as me," Acouth says.

"When migrants and asylum seekers are coming to Australia they are fleeing their country because of persecution or civil war. They leave their countries because they don’t have a choice. They look for success and ask themselves, how can I make the most of the opportunities and give back to the country that has taken me in?"

While debate rages around the country about the Australian government's decision to issue 12,000 visas to refugees from Syria and Iraq, Acouth offers some advice for those who fear an influx of asylum seekers.

"You see stories here and there that are negative, but I can tell you that the majority of asylum seekers here are doing or trying to do good things. Instead of seeing migrants as trouble, especially from an African background, you shouldn't judge, because these young ones just want to be accepted and to succeed".