Jack O'Connell looks scared shitless throughout most of '71.

And that fear only ratchets up the tension in the film, which opens in limited release this weekend along with the Salma Hayek-fronted Everly, both of which try what you might call a narrow-focus approach to action, centering on a character who's isolated, desperate, and only able to react.

To be clear, scared shitless is an expression O'Connell wears well. A strapping twentysomething who resembles a seasoned bruiser from some angles and an unguarded kid from others, the British actor was shockingly good as a tough teenager thrown in with the hardened grown-ups in last year's bracing prison movie Starred Up. O'Connell's just as impressive as another out-of-his-depth newcomer in director Yann Demange's (Dead Set) feature film debut, in which he plays a soldier-in-training whose first appearance on screen comes with a face bloodied from a boxing match. (Ironically, the actor's most recent role, in Angelina Jolie's Unbroken, gave him a shot at mainstream stardom but offered him the least to work with, putting his character in the position of a martyr rather than a man.)

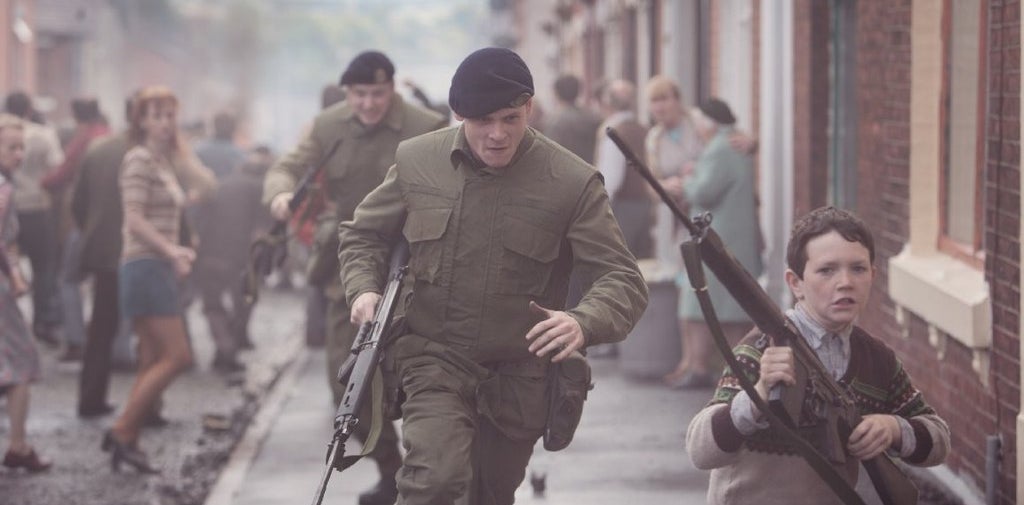

The film '71 tracks O'Connell's character, Gary Hook, through the streets of Belfast during one tumultuous night during the early days of the Troubles. Hook's squadron has been deployed to help with what's been described to them as the "deteriorating security situation" in the area. They're theoretically around to assist the police, but the reality they arrive in is an urban war zone, and their first day out goes sickeningly wrong. What was meant to be a search of houses for weapons escalates into a riot, and Hook and another soldier get left behind in the chaos. When his colleague is shot, right in the middle of street, by members of an IRA faction, Hook takes off running.

The movie's got some crackerjack action sequences, but that first chase, in which Hook runs for his life through unfamiliar streets and back alleys, provides the starting adrenaline-addled jolt. Demange, working off a script by Gregory Burke, builds up the day's unrest gradually before then — the soldiers are entertained by boys hurling urine-filled water balloons and invective at them over the fence, but then they roll up into a neighborhood where the local women bang trashcan lids on the sidewalk as a warning of their arrival, and hostile crowds quickly gather. The sight of the police dragging a man out of his house and openly beating him as part of their interrogation kicks off the violence, and the execution of Hook's comrade is the shocking sign of how far some are willing to take it. In the space of a second, Hook is turned from soldier to panicked prey, scurrying away while ducking gunshots, and the camera follows him like it's also fleeing, at times showing his point of view as he weaves through streets filled with burnt-out cars and people who may or may not wish him harm.

That uncertainty saturates '71, which sometimes pulls back to reveal the clashing powers at work beyond Hook's awareness — the Protestant paramilitary, the warring offshoots of the IRA, the undercover officers illicitly playing off both sides, the main army forces, and the citizens left with no choice but to declare their affiliation. The film doesn't lend its sympathy to any one side, instead grimly depicting how convictions, ego, and aggression from all parties will fuel more fighting. The bigger-picture moments only emphasize how lost Hook is, trying to survive the night and to work out whether or not to trust the strangers he encounters — though there are some familiar figures who can't be relied upon either. Belfast, alight with the flames of automotive fires and Molotov cocktails, looks like a true conflict zone, but then Hook ducks into a pub or apartment and there's a vertiginous air of normalcy, because day-to-day life also continues. Dazed and wounded, Hook's the opposite of the swaggering action hero, looking increasingly traumatized as '71 tracks him through his terrible, thrilling night, teasing whether or not he'll see the dawn.

The title captive in Everly, played gamely by Salma Hayek, isn't your standard tough character either, though she takes to guns, grenades, and a variety of sharp-edged weapons quickly as the movie goes along. Directed by Joe Lynch, the filmmaker behind the LARPer horror comedy Knights of Badassdom, Everly is a sort of shut-in's tribute to Kill Bill in which the female lead takes her revenge on her former lover, reconnects with her child, and kills tons of people. The twist in Lynch's film is that she never leaves the apartment in which she's been held for the past four years, having been kidnapped as part of a sex-trafficking ring, only to be chosen by the boss, Taiko (Hiroyuki Watanabe), to service him personally.

Everly, which is also available for digital rental, is an unapologetic and unsurprising mishmash of Quentin Tarantino, extreme Japanese cinema, and video game tics. It's also an excuse to have Hayek strut around in a lacy slip and with a handgun and, more unpleasantly, to start her journey by being gang-raped, an incident the audience can only hear and that the film treats with an upsetting glibness. It attests to the movie's interest in serving up a concentrated dose of fanboy indulgence meant only for a very specific audience — but there is one thing to the single-location setup that lingers when all the gore has faded from memory.

Everly's mother (Laura Cepeda) has been taking care of her granddaughter since her daughter vanished without a trace, and Everly ends up summoning the two of them to her place to pick up money she's saved so that they can disappear. In the midst of the carnage, Everly suddenly finds herself prepping her apartment for a maternal visit, nervously cleaning, trying out presentable outfits, and stacking corpses in the closet. Limiting the film's action to a spacious but contained loft is a gimmick (and a budget-saver), but in that moment, it allows the hard-charging main character to become just another nervous person trying to convince her parent that her life as a grown-up is under control. Everly's a stylized as '71 is unfussily gritty, but for that moment, it's weirdly real. Then the rocket launchers come out, and it all goes to hell.