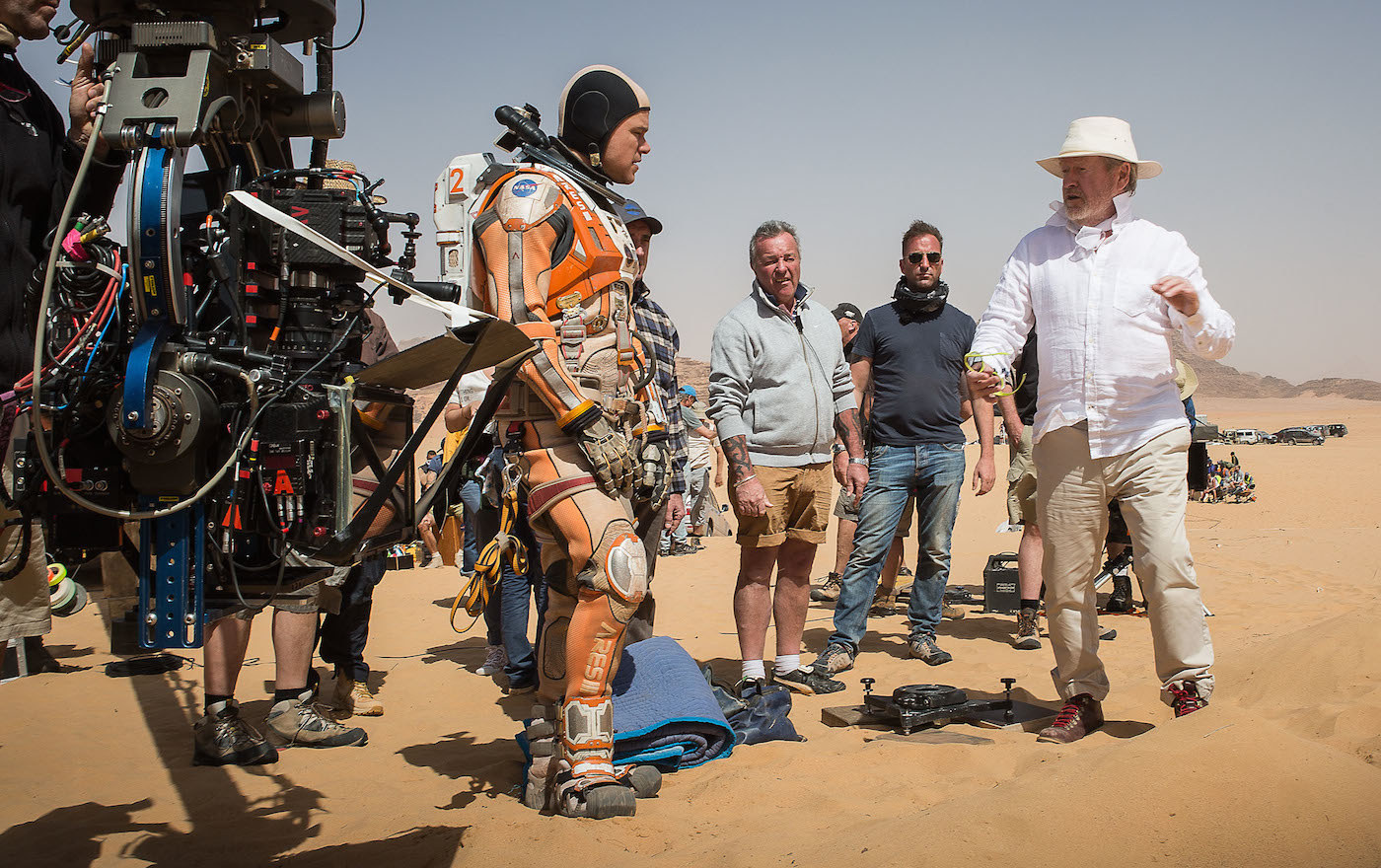

Matt Damon has won wide acclaim for his performance in The Martian as astronaut Mark Watney, stranded on the planet Mars after a freak accident. And Ridley Scott has been heralded for his assured and expert direction of the herculean efforts by Watney to stay alive and his NASA colleagues to rescue him. But the reason Damon signed on to the film, and the reason Scott agreed to direct it — the reason, really, this film exists — is due to the screenplay, from writer Drew Goddard (World War Z, The Cabin in the Woods).

That script is based on the novel by Andy Weir, which was first published for free on Weir’s website, then as a popular 99-cent e-book, then as a wildly popular hardcover best-seller. Goddard, who quite literally grew up surrounded by rocket scientists in Los Alamos, New Mexico, first received a copy of Weir's book from The Martian producers Simon Kinberg and Aditya Sood in 2013, between its life on the Kindle store and as a printed novel.

"I usually say no to everything," Goddard told BuzzFeed News in a recent interview in a bright Hollywood office conference room. "I prefer to self-generate. But I read it, and then the next day, I read it again. And then the next day, I read it again. And I said to my wife, 'I'm really thinking about this one.' And she said, 'Well, why?' I start telling her what it's about, and she said, 'Oh, so it's about scientists? Well, dummy, it's about your hometown for you.'"

Shortly thereafter, Goddard said yes. "I felt like Andy had captured scientists in a way that I had never seen, but yet was very familiar to me in real life," he said. Capturing that feeling in a screenplay, however, presented two formidable challenges for Goddard: One, Watney spends virtually the entire movie by himself, recording his experience via a first-person narrative, which does not exactly scream cinematic. And two, practically the entire plot of the movie hinges on, as Goddard put it, "dense scientific jargon," which screams, quite loudly, not cinematic at all!

And yet, The Martian, which had an outstanding $54.3 million opening weekend, is one of the most arresting feature films of the year precisely because it embraces Weir's love of using science to solve problems — without letting that jargon overtake the film. "The way Drew did it, it makes really good horse sense," Damon told BuzzFeed News in August. "It made sense to me, and I assumed it would make sense to the rest of the audience. Rather than kind of get lost in the weeds, he just does the peanut butter and jelly version of what you need to do. … I mean, it cut down on my workload, because my marching orders were pretty clear."

For his part, Weir recently told BuzzFeed science writer Alex Kasprak that he was surprised by how much Goddard wanted to keep to his novel. "From Day 1, he just said, 'Hey, I liked this book a lot so I just want to make a movie version of it. I don't want to change a bunch of stuff,'" Weir said. "This is just basically my book in script form — with stuff taken out of course, because otherwise it would be a 10-hour movie."

Throughout the adaptation process, Goddard said he worked hard to keep two principles in mind. "I need to love it, and if I love it, then I trust that I will protect what needs to be protected because I love it," he said. "And the second one is you have to really make peace with the fact that your job is not to karaoke the book. Your job is to make a good movie. You hope that if you have both of those two things in mind, you'll do your job well. But if it's only one, you're gonna really screw things up."

Goddard talked BuzzFeed News through his entire process of winnowing down Weir's book into a tight screenplay, including some painful cuts and changes he had to make, why he was actually thrilled to get notes from the studio, and the literal number of fucks he could give in the script. (Naturally, MAJOR SPOILERS from the film and the book follow.)

Outline, outline, outline.

Goddard learned an important rule from his time working as a writer on Joss Whedon's TV series Buffy the Vampire Slayer and Angel, and he keeps to it when he starts any writing project: "I work really hard on fuckin' outlines," he said. "This is Joss training."

Goddard said he spent three months on the major outline of the story, and then roughly five weeks writing the first draft of the script itself. His biggest advantage was that Weir's story fit rather neatly into a standard three-act structure, as Watney transforms his habitat (or Hab) he calls home into a makeshift garden to grow potato plants, NASA and Jet Propulsion Lab officials strategize on the best way to get him home, and Watney's crewmates from his aborted mission decide to turn their craft, the Hermes, around and head back to Mars to save him. "At the end of act one, Mark Watney makes contact with Earth," said Goddard. "Midpoint, the Hab explodes, and Hermes turns around. And then act three is the rescue. So I sort of knew, OK, here are my acts. Now I know how much room I have to play between each of those signposts."

The changes can start on page one.

Despite having a clear blueprint to work with, Goddard still ended up having to make a major change starting on the very first page. In Weir's book, Watney's mission on Mars, called Ares 3, ends on the sixth day, or "sol" going by the Mars clock, when a massive dust storm forces the crew to abort and head home, and strands Watney after he is struck by an antenna and presumed dead. In the movie, however, that mission ends much later, on sol 18, a somewhat last-minute change requested by Scott before production began.

"It was so tragic that they had to leave after six sols," said Goddard. "He wanted to get a sense the team was working [on Mars] so that you understand that this work was important." But, according to Goddard, Scott was also concerned about the supplies of human waste Watney needed to use as fertilizer in order to grow enough crops to survive. "He wanted to make sure there was enough feces, that you could have generated enough, which is a great note," Goddard said with a laugh.

Scott's decision, however, meant that Goddard had to rework all the precise math Watney had done in the film to calculate how many rations he had left in order to know how many potatoes he needed to grow. "My brain just starts going, Oh no," Goddard remembered. "’Cause I realize that changes not just one scene, every scene. But that's why you get paid is to go do that math. I would do it, and then I would call Andy Weir, and say, 'Does this make sense?' He would always double-check me, and at times just say, 'No, you're an idiot.'"

You need to ration how many "fucks" you can give.

The MPAA has a rather ironclad rule that you can only say "fuck" once in a PG-13 movie, and Goddard spent it on the moment after Watney had gone through a harrowing bit of self-surgery to pull out the antenna that had impaled him. "I knew that that first 'fuck' was crucial," the screenwriter said. "It's funny, because we tested a version without that first 'fuck,' and scores dropped dramatically. When you watch the movie, you realize, Oh, it's so intense, and then he says 'fuck,' and it tells the audience it's OK to laugh. So you really understand the tone of the movie."

Later in the movie, however, Damon improvised the line "Fuck you, Mars," and everyone loved the moment so much, the filmmakers did a bit of horse-trading with the MPAA in order to keep the second fuck and the PG-13 rating. "There was an insult in there like 'ass filcher,' and the MPAA said, 'No, you can't have 'ass filcher' in your PG-13 movie,'" Weir explained. "They're like, 'Oh, come on. If you're going to make us get rid of filching, give us a fuck.'"

Clarity will always win over detailed precision.

At many points throughout Weir's novel, Watney spends countless paragraphs detailing the complicated equipment that is keeping him alive, things like the water reclaimer, oxygenator, and atmospheric regulator. It is engrossing to read about on the page, but Goddard barely plays lip service to it in the film. "We were asking a lot of the audience right away," he said. "You're like, This is going to be a movie about farming in your own shit. And at a certain point, it's this balance of, Have we veered too much into the intellectual world and forgotten the emotional world? You'll cling to, Oh, he's getting food. Oh, he's getting water. When you get into the complications of NASA equipment, it just gets hard."

That also meant that Goddard gave Watney detailed maps of the Mars surface — something he is sorely missing in Weir's novel — so the audience could see him plot out his journey. "None of us have a real sense of what Mars' geography is like, so if you say you're going to Acidalia Planitia, who knows what that means?" he said. "We struggled with making journeys clear to the audience so that it felt like you could understand."

"Andy lecturing me about how dumb I am delighted me so much so I just put it in the movie."

One of Goddard's favorite changes for clarity, however, came from Weir. Toward the end of both the book and the film, NASA instructs Watney to strip down the pod, called the MAV, that will blast him back into space, so he can reach his crew waiting to rescue him in orbit. And Goddard decided to add a scene in which Watney describes his feelings about those particularly insane instructions. "I felt like the more we can talk about it, the more it will help set up what's about to happen, ’cause I knew we wouldn't be able to talk about it while it's happening," he said. "I remember calling Andy and saying, 'OK, I want to put this scene in, but I want to make it really simple for the audience. So I want him to say, fastest man in the history of space travel.' And Andy said, 'Well, a physicist would never say that, because it's all about velocity.' Andy lecturing me about how dumb I am delighted me so much so I just put it in the movie."

Music matters.

Goddard loved Weir's conceit that Watney would be stuck listening to his crewmate's collection of ’70s disco music that he wrote every disco music cue right into his script. "A, I wanted the studio to understand that we needed a large music budget," he said with a chuckle. "And B, I just thought it was so important that you could really track the emotion of the character. It was one of the things that frankly made me say yes to the project right away. I think I have the emails back and forth with Simon Kinberg at the beginning when we were talking about whether or not we should do this. And I said, 'I'm driving around in my car listening to ’70s hits and thinking about Mark driving across Mars, and I'm crying.' I feel like that's what this movie is. I think I pitched that in the Fox meeting: 'If you picture a man destroying a spaceship to [ABBA's] "Waterloo," that's our movie.'"

It's important to heed input from your director, star, and even your studio.

One of the most powerful moments in Weir's novel comes after Watney travels several days to find the old Pathfinder probe and rover, and repairs it enough to communicate with Earth. After receiving his first signal from NASA, Watney breaks down crying. In the film, however, Watney celebrates instead by screaming, "Woo hoo!" — without a tear in sight.

"That was Matt's instinct, [and] he was right," said Goddard. "The idea was, Let's just save it ’til the third act." In the film, Watney doesn't turn on the waterworks until just before he’s about to blast off and head back to the Hermes, when he talks with his commander, Lewis (Jessica Chastain). "That moment is where you really break."

It was just one example of how willing Goddard was to always chase after the best idea in the room — and often those ideas came from Scott. In Weir's novel, the Hab and the Hermes are both cramped, utilitarian spaces, but the movie makes them both look relatively palatial in size and beauty. "I think Andy and I both said, 'Well, wait a minute. This is supposed to be intimate and small,'" said Goddard. "And Ridley would look at us and laugh and go, 'But look.' And then he'd show us what it'd look like. And you'd go, 'OK, well, that looks amazing, so we should just do that.' That is definitely moviemaking. You realize, No, no, you've got to put something onscreen. … The book will always exist. And Andy was great, by the way. He was like, 'Make it better, Ridley.'"

Elsewhere, Scott requested that Goddard compress the scene in which one of the airlocks rips and explodes out of the Hab. In the book, Watley is trapped inside the airlock for 24 hours as he tries to repair a leak in his suit and the airlock walls. In the film, Watley slaps some duct tape on his helmet and is good to go. "I wrote in the first couple drafts very close to the book, because one of the things I loved was not knowing where the airlock was leaking and him lighting his own hair on fire [to use the smoke to find the leak]. Ridley sort of said, Yes, this sounds good in theory, but lighting hair on fire and shooting that in a way that the audience understands what's going on is going to be very difficult and challenging. And I trusted him on that, ’cause I understand from having directed, if you can't see it in your head, you're never going to be able to convey it to any audience."

Goddard even happily took notes from the studio, specifically for the scene in which astrodynamicist Rich Parnell (Donald Glover) explains the maneuver that will allow the Hermes to slingshot around Earth and head back to Mars to save Watney. In the first draft of Goddard's script, Rich explains the maneuver to Vincent Kapoor (Chiwetel Ejiofor), the director of Mars operations, and then Vincent explains it again to the rest of the NASA team. "So you have two problems," said Goddard. "One, it's just two guys talking, which you try to avoid if you can. And two, you have two people explaining the same thing back-to-back. And the studio just said, 'Can you just put Rich in that [second] scene?' It was one of those notes where you're like, Why didn't I think of that, goddamnit?"

But sometimes, it is important not to heed your director.

When Watney goes on long missions in his rover that last for several days, Weir spends a fair amount of ink detailing how he copes with going to the bathroom in a vehicle that was never designed for him to do that. Those scenes, however, are not in the finished film — but not from lack of trying by the film's director.

"We shot it,” said Goddard. “Ridley was very interested in it, almost to a hilarious degree. And I get it. He wants the reality of it to really feel real. So there are scenes of Mark going to the bathroom. We have them. Maybe they'll be on the DVD. But I think at a certain point, let's call it a shit tolerance. There's just a certain amount of shit we can watch onscreen."

Movies move, and you must maintain that momentum at all times.

Goddard and Scott were perhaps the most ruthless when it came to keeping the film brisk and moving forward. Sometimes, those cuts came in the editing room, like when Scott cut the scene in which Lewis makes clear that she knows her crewmates Beck (Sebastian Stan) and Johanssen (Kate Mara) are shacking up. "The first cut of the movie is like three hours, and at a certain point, you just gotta make some tough decisions," said Goddard. But sometimes, those cuts came at the script stage, like when Goddard cut the scene in which Watney flips his rover as it enters a massive crater. "I didn't want to just have complications for the sake of complications. You want each complication to have an emotional reason, to tell you something about Mark’s character. At that point, you understood his worldview and what he does,” Goddard noted.

His biggest changes came in the book's second half, starting with the moment in which Watney loses contact with NASA after he accidentally shorts out the Pathfinder. It drastically raises the stakes in the novel — Watney doesn't regain communication with NASA until the end of his 2,500-mile journey from the Hab to the craft he's taking back to the Hermes. But for the movie, losing touch with Earth became an obstacle for the storytelling. "We have so much exposition to get across, and if they cannot communicate with one another, it was hard to get the exposition," said Goddard. "That was a section that, if you just did what the book did, that would've been 60 pages right there — at least. I remember telling Andy, 'This is where it's going to get hard.' But Andy knew. He's like, 'Look, 80 pages of journey can become a three-minute montage, and it'll work.'"

Sometimes, you've got to cut the things you love.

Goddard had to make one of his most heartbreaking cuts from those 80 pages of journey: the fine dust cloud that threatens to cut off Watney's access to the solar power he needs to survive during that 2,500-mile journey. Without communication, NASA is unable to warn Watney that it's coming, and the cloud is indistinct enough that Watney can't quite make it out with the naked eye. Even when he does realize something is up, it is impossible for him to know how big the cloud is, or in which direction it is headed.

"I feel like the heart of the book is about that dust storm," said Goddard. "One of the first things I said is, 'This book is almost a religious book. It's just that the religion is science.' … We have cut Mark off from everything. And he is stuck on his own, and it's where the real crisis of faith comes in. So if you're viewing it as a religious text, it's where he's just talking to his god. He's just like, 'God, get me out of this,' and the world is watching."

"You learned never to say 'This is my favorite part of the script' out loud."

But Goddard also knew that a dust cloud is an awfully static visual on which to hang a crisis of faith. Plus, he explained, "I just didn't buy that he would be saying to the camera, 'Let me explain to you what I'm doing.' So then what that becomes is just a guy doing math, but you don't know why he's doing math." Goddard paused for a moment. "You could have the NASA side explain the problem and hope that he's figuring it out. It just didn't feel visceral. I'm sure there's a version that could've worked visually. I just couldn't crack it, to be honest."

But Goddard was able to crack one of the most abstract sections of Weir's novel, when the narrative suddenly leaves Watney's point of view and goes into a detailed description of how the canvas that makes up the Hab was manufactured, how that canvas was stressed beyond its specifications due to Watney's prolonged use, and how that canvas eventually ripped, causing that aforementioned airlock explosion. "I loved it so much," he said. "I remember going back to my TV days, you learned never to say 'This is my favorite part of the script' out loud. ’Cause as soon as you said it out loud, the screenwriting gods can be cruel, and they will cut it. I remember thinking that, because I had the Hab flashback that shows essentially the history of how you build something. It delighted me. I loved the process of it. And I knew it was going to get cut. Even writing it, I knew I was going to have to cut it one day. It's going to be wildly expensive for a scene with no actors and a flashback. And Ridley sensibly was like, 'We can spend that money somewhere else, so let's cut it.'"

But sometimes, you get to keep the things you love.

In a very geeky movie featuring very geeky science, the geekiest moment of all features Rich Parnell explaining his Hermes maneuver to several NASA executives — including PR director Annie Montrose (Kristen Wiig), flight director Mitch Henderson (Sean Bean), and NASA director Teddy Sanders (Jeff Daniels). In order to keep the meeting a secret, they give it a code name: the Council of Elrond. As in the scene from The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring, when the major characters meet in secret — including one played by Sean Bean.

Goddard said the decision to cast Bean came relatively late in the preproduction process. "There was definitely a moment of, 'Do we need to change it?'" he said, still smiling at the memory. "And I was like, 'Absolutely not. It's way better when he says it.' Every time we screen it, when [Bean] says, 'Because it's a secret meeting,' three people in the theater laugh. And I look around and go, 'Those are my people.'"

Although the Council of Elrond scene comes from Weir's novel, Goddard did add the joke in which Teddy asks that his code name be the elven warrior Glorfindel. "That might be the thing I'm most proud of in the movie."

You have to keep your hero heroic.

In Weir's book, when Watney rides up in the MAV to the Hermes — and after some difficulty getting both crafts to line up closely enough — he is rescued by Beck from the MAV and pulled by a tether back into the Hermes. But that climax proved to be a problem twice over for the film. "In cinematic terms, you're going to have a situation where your protagonist is entirely passive for the third act," Goddard said. "That just jumped out as a problem to me. The whole movie is about Mark adapting to save himself, and I felt like you want that to happen in the third act." So Goddard had Watney act on a suggestion he makes in the book, which is to "fly around like Iron Man" by puncturing his glove.

And second, Goddard had identified Watney's platonic bond with Cmdr. Lewis as the central relationship in the film, especially given Lewis's guilt for making the call to leave Watney behind. "I wrote the first draft with Beck [rescuing Watney]. And it just felt wrong." So instead, Goddard decided to have Lewis step in at the last minute to be the one to rescue Watney. "You just say, ‘OK, the whole movie is building to that,’ so just do it. … You have to trust your instinct."

But you don't have to give your hero a love interest — just a consistent motivation.

Some of the trailers for The Martian make it seem like Watney has a wife and child back on Earth, a trick of editing that uses a scene of a different character video chatting with his family. But Goddard felt strongly that he did not want to give Watney any strong emotional attachments to family back on Earth. "If you do that, it becomes about getting home to your wife,” he said. “And I felt really strongly that this wasn't about that. On the one hand, it is about saving Mark, but it's not really. It's about Mark living — the act of living — and that he has a skill set that keeps him alive."

In lieu of a love interest, Goddard zeroed in on Watney's first instinct to make clear that he does not hold his Ares 3 crewmates responsible for leaving him behind. It's a point Goddard chose to emphasize in the script by amping up the conflict between Watney and NASA over their decision not to tell the Hermes crew that he survived.

"This is a man who's just been left for dead, and his first instinct is to protect his crew," said Goddard. "And that's everyone's first instinct in this book: to protect each other rather than their own self-interests. I really like that. … At a certain point, you have to go, What's the emotional truth to this movie? All of the science and all of the plot, it doesn't matter. That's what was beaten into my head by Joss in the early years: None of it matters except the emotion. And I felt like the emotional story is, this is a movie about people taking care of each other."

Your movie can inform your own life.

When conceiving the film's final moments, Goddard decided the best way for The Martian to end is with the launch of the Ares 5 mission back to Mars, as the film checks in on the whereabouts of each of the major characters. "I remember in the course of writing it, I just started to feel like they talk so much about Ares 5. I like the spirit of this movie: We do our best, we fuck up, we do a little better, we fuck up, we do a little better. And it just rolls on, you know?"

That philosophy became quite handy for Goddard soon after he turned in the final draft of the script at the end of 2013. He was actually attached to The Martian as a director as well, which made for a busy plate, along with his commitment to create and run Marvel's Daredevil TV series for Netflix, and write and direct the Spider-Man villain film Sinister Six for Sony Pictures. The initial plan was that Goddard would finish the first season of Daredevil, then direct The Martian, and then direct Sinister Six.

But things did not go to plan. "I sort of had my day of reckoning, as I like to call it," Goddard said with a laugh. On the same day in 2014, Goddard said that he learned all three projects had received a greenlight to begin production — and that Sony wanted to move Sinister Six's release date up two years, from 2018 to 2016. "It was one of those days that you're like, Is this really happening?" Goddard recalled. But much like Mark Watney, Goddard did not let a sudden, highly disruptive setback slow him down. "I called [Marvel], and I called [Fox] and I said, 'Here's the problem we have, guys. Let's talk about how to solve it.'"

The solution: Goddard stepped down as the showrunner for Daredevil (replaced by fellow Buffy alum Steven S. DeKnight for Season 1), and as the director of The Martian. Ironically, however, Sinister Six was placed in limbo earlier this year after Sony struck a deal with Marvel Studios to reboot the Spider-Man franchise with actor Tom Holland. "I wrote it so that it could exist on its own, and slot into any Spider-Man continuity," Goddard said. "So it could happen. At some point, maybe, if it falls into [Marvel and Sony's] plans."

But if he has any hard feelings, Goddard does not betray them. "Hollywood is very volatile," he said with a shrug. "You have to make tough decisions as a director. It just happens. … Fox said, 'Listen, why don't we talk about directors that you'd be thrilled to have. We'll go to those directors. If they say yes, then we'll make that movie. And if not, we'll wait for you.' I said, 'Great!' Ridley was No. 1 on the list. We sent it to Ridley, and he said yes that night. So suddenly, that problem was easy to solve. Like, it was never really a problem. I sorta felt like, Can you guys be more sad? It feels like I just broke up with a girl, and now she's dating George Clooney."