"So you're catching me in full crisis mode."

These are the first words Hans Zimmer says to me when I step inside his Santa Monica, Calif., office. He's perched on a plush red couch festooned with pillows, next to a Sony Pictures executive working hard to ignore Zimmer's general air of polite agitation. A film composer for almost 30 years, Zimmer has been nominated nine times for an Oscar, and won once (for 1994's The Lion King). For decades, he has created music for practically every stripe of feature film, from animated family films (Kung Fu Panda) to romantic comedies (The Holiday), sweeping historical epics (The Thin Red Line) to comic book Hollywood spectacles (The Dark Knight Rises). This year alone, Zimmer wrote the scores for no less than four major motion pictures: Man of Steel and The Lone Ranger this past summer, and Rush and 12 Years a Slave this fall. He is, quite simply, one of the most successful and in-demand film composers working in Hollywood today.

But at this moment, Zimmer is under the gun to deliver music not for a movie, but for a movie trailer — namely for next summer's The Amazing Spider-Man 2. Zimmer is also writing the full score for the film itself for director Marc Webb, which won't need to be delivered for many more months. But by midnight that mid-October night, Zimmer has to deliver his final cut of a brand-new composition for the film's first trailer, a highly unusual undertaking for a film composer of Zimmer's stature. (Usually, trailers use scores from other similar movies, or generic music composed specifically with trailers in mind.)

Later, I would get a far better picture of why Zimmer got himself into this particular dilemma. But at that moment, just as the tight deadline looming overtop him seems to turn his mood gloomy, Zimmer swings effortlessly back into a much more playful one. "You're catching us in our full Spidey onesies," he says with a laugh, leaning back into his sofa. "With feet!"

One need only to look around Zimmer's surroundings to understand why he has such a hard time staying in a bad mood. It is part workspace, part filmmaker lounge, part creativity incubation chamber, part working museum of electronic music, and Zimmer has spent well over a decade in this room giving birth to some of the most memorable movie music in recent Hollywood history. Even with his Spidey deadline imminent, he graciously agreed to give BuzzFeed a tour of his studio, and in doing so, he revealed how the room has in many ways come to define him.

Or as he puts it, "It's sort of the inside of my brain." Let's step inside.

The Room

Zimmer's studio was born from a period of profound homesickness. Born and raised in Germany, Zimmer first moved to Hollywood in the 1990s after cutting his teeth as an indie film composer in London. By the time he discovered the room that would become his main studio, Zimmer had already won an Oscar and catapulted himself into the upper echelon of Hollywood film composers, but he found himself yearning for his home in Europe.

"This was a midlife crisis moment when I was going to leave everything behind and go back to Europe," says Zimmer, now 56. "I was never going to have a midlife crisis which involved a yellow Ferrari and blonde to go with it. I realized the bit of Europe that I was missing didn't exist anyway. The very obvious thought came to me: I'm living in Hollywood — just build it!"

At this point, Zimmer turns to the Sony exec who had been studiously avoiding becoming a part of the interview. "Do I want to say what really the inspiration was?" he asks her. Once more, the exec resolutely says nothing, but that's enough of an answer for Zimmer. "Oh, god, she's daring me. The head of music at Sony thinks that I should come clean and say that part of the inspiration was a 19th century brothel in Vienna."

The description is an apt one. The entire room is suffused with various forms of lushly baroque red upholstery and wallpaper, even on the ceiling. But perhaps chagrinned by forcing an unsuspecting studio exec to be complicit in his revelation, Zimmer immediately offers another, more wholesome — if no less nostalgic — aesthetic inspiration for his studio. "Just down the road from where I lived [in Germany], lived this remarkable man who restored cathedrals in Strasbourg and Cologne," he says. "He lived in a medieval tower and had a 2,500-pipe church organ. And as a kid, that was really where I got to learn and appreciate music, because as a 6-year-old I could just go next door over to his place, fire up the church organ, and make an ungodly racket. Everybody in the town probably thought it was an ungodly racket, but this guy kept saying, 'No, it's great. Listen to his daring harmonies.' Well, daring harmonies is a 6-year-old putting his elbows on the keyboard."

The Instruments

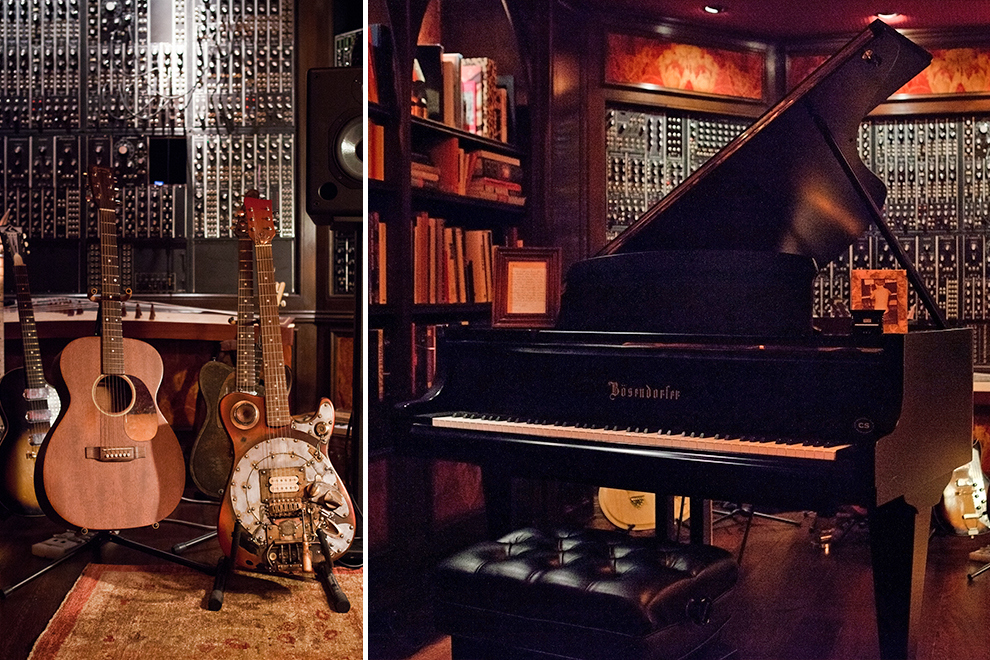

Eventually, Zimmer moved on from pipe organs to a much more modern instrument: The electronic synthesizer. Musicians and inventors have been crafting electronic musical instruments since the turn of the 20th century, but the "modern" synthesizer is about as old as Zimmer, first coming into vogue in the 1960s thanks to the innovation of R.A. (Bob) Moog. These aren't the disposable plastic keyboards that became ubiquitous in the 1980s — they are large decks of electronic equipment engineered to create sound through internal hardware and physical dials as well as keyboards, and Zimmer's office is stuffed with them.

"I got this all this stuff when everybody was throwing it out because they were going, 'Digital is the future,'" says Zimmer. He points to a large deck in one corner of his studio. "I'm just going to make people really envious here, but, like, that synth, it's a Roland. I remember phoning the company and saying, 'Do you still have any of those?' And they go, 'Yeah, we've got a whole warehouse full. It's cluttering up the warehouse. Do you want them?' I said, 'Yeah, so what are you asking for them?' And they said, 'Will you take it by the pound? How about $25 a kilo?' Which is ridiculous. Now, if you go into eBay, a five-module system is $2,500 minimum."

Even though Zimmer could work exclusively with computer software to digitally synthesize the sounds of analog synthesizers, he still often turns to the "primeval" machines for inspiration. "There are some really interesting things that are happening in software, but it's how you frame a picture," he says. "Even if I use all the modern bits and pieces, it's nice that even at the core, you have this wild electronic beating heart going on. ... Last week, I tried to write my Spider-Man [trailer] opus, and I'm stuck on it, and plug in a 40-year-old mini-Moog, and was going, 'Oh, wow! This thing is living and breathing.' It spits back at me. It's great."

There are several other instruments scattered about the room, including a forest of electric guitars, and a Bösendorfer piano that Zimmer proudly declares helped win him a competition to the company factory in Vienna. These aren't for display. Zimmer is adamant that any instruments that live in his studio have been and will be played, and often: "If it doesn't make a good noise, it shouldn't be in here." (The guitars, for instance, show up on Zimmer's energetic score for director Ron Howard's Formula One racing drama Rush.) But Zimmer also confesses that the only instrument he feels truly qualified to play is the computer.

"I'm not a good pianist," he says. "I always thought I wasn't worthy of a Bösendorfer. I'm a composer. I'm not an interpreter. Great musicians, they play challenging things all day long. I make things up in my head. It's not about the dexterity of my fingers. But I'm a really good programmer. You put me in front of a computer, that's my way of getting my music in."

The Computers

At the center of Zimmer's studio sits a steel desk that houses a computer workstation so confoundingly elaborate that I'm not surprised at all when Zimmer tells me he and his team at his company, Remote Control Productions, built the system from scratch themselves. For Zimmer, it is all about removing as many possible impediments between the ideas in his head and the notes on the screen, allowing for as pure a creative experience as possible.

"When I first came to Hollywood, most people were still writing [music] on pieces of paper," he says. "The first time a director would actually get to hear something would be when the orchestra was wheeled in, which I didn't think was very efficient. I mean, there's a huge emotional distance playing somebody something on a piano and shouting at them, 'This is where the French horns come in!' as opposed to at least [playing] an imitation of the French horns coming in."

Over the years, Zimmer has modified and enhanced his system, including, say, a touchscreen system built for all the sub-menu options he'd been wasting precious seconds scrolling to select. "You stop playing, you have to look where your cursor is, you have to drag it over, and half of the idea is gone," he says, deadly serious. He is also adamant that the system remain as rock solid as possible. "The first rule is it can't crash. There's nothing worse than having an idea and you can't do it because the thing has just crashed. You feel the gods are against you or something. I mean, I take it very personally when the computer crashes." (Ironically, Zimmer long ago abandoned the enormous speakers he installed in the wall in front of his workstation when he first renovated the studio after working on Gladiator in 2000. "Bad idea," he says. "The speakers were killing me, because it's so loud you can't think, and they don't sound good unless you really turn them up.")

When he's seated at his multitude of monitors and ready to work, Zimmer's actual process involves a great deal of tinkering — another way of saying he is an expert procrastinator. "I'm a great fiddler," he says. "Hours can be spent not writing things, making noises. But that's part of the process. I can never quite make up my mind if my life is the life of a chef, and you go shopping, and you're like, 'Oh, look, the carrots look fresh,' and you get it home and you spend a long time chopping carrots, and then at the end of the day, you know the guests are coming at 8, and you throw it into a pot. Or if I'm a painter and I'm just trying to figure out what the colors are I want to use. Somewhere, a bit of both is going on. The notes come last."

The Inspiration

If something in Zimmer's studio isn't meant to be played — like the piano, the guitars, the synthesizers, and the computer — it is meant to inspire.

One example: He has a real working fireplace, a rarity in wildfire-friendly Los Angeles. "Sometimes we get really naughty and turn the air-conditioning really cold, put the fire on, and have far too much red wine," Zimmer says with a grin. "It depends on the movie. It's more of the R-rated movies." Above the fireplace on the mantle sit photos of his family; a Kung Fu Panda statue; an award Zimmer can only vaguely recall; and an impossibly cool steampunk clock ("made out of Russian submarine parts, basically").

Zimmer is perhaps most proud of the framed (and, in some circles, NSFW) piece of art hanging above it all, by the early 20th century Austrian expressionist Egon Schiele. "I think in your workspace, you've got to have one complete fuck-off piece of art. I don't know how else to say it."

In truth, Zimmer has all kinds of art surrounding every nook and cranny of his studio. There are mementos of his past films, like an empty jug of tequila surrounded by barbwire given to Zimmer by Rango director Gore Verbinski as a reminder of the film's spirit. ("It was full, I believe, at one point.") Or Capt. Jack Sparrow's sword, requested by Zimmer for his young son. ("It arrived and it turns out, it's real steel and you can kill somebody with it. So I put it in a case.") There are loads of art books and a small library of classical composers. There's a framed copy of Mozart's "Ave Verum Corpus," which Zimmer calls "the perfect piece of music." The room is basically engineered for creativity.

"It doesn't matter if it's the director, the editor, or musicians, or whatever, we can get together and we talk," he says. Zimmer points to where I am sitting and says that both Ron Howard and 12 Years a Slave director Steve McQueen had sat in the same spot, ruminating with him over the best way to use music to key into their respective films' stories. "We come up with ideas and then we can do them instantly. … You have to feel very comfortable with your director to go and say, 'Here, I have the worst idea, and I'm just going to go put my hands on the keyboard now and play the worst idea.' But, I mean, that's the relationship I try to have with my directors. You throw yourself into the deep end and go, 'I feel no shame.'"

The Collaboration

It is right after Zimmer finishes telling another story about feeling no shame — how The Holiday director Nancy Meyers sent him a couch from the film after he openly admired it — that another of Zimmer's directors, The Amazing Spider-Man 2's Marc Webb, steps into the room.

As Webb arrives, Zimmer greets him with a smile and a weary wave, and I realize that my presence was another elaborate way for Zimmer to procrastinate finishing the task at hand. Zimmer's alarmist attitude comes rushing back.

Hans Zimmer: What you need to know is we're in full-on crisis mode, I think is a fair way of saying it.

Marc Webb: Crisis mode? Really? That's so dramatic.

HZ: No no no. We're working on a really good movie, but somebody is trying to force us into delivering a trailer like now.

MW: Composers don't normally do trailers. There was this terrible temp dub-step music and it fucking sucks. [To Zimmer:] You saw the trailer before I did.

HZ: Yes.

MW: And he was like, "It's just shit!"

HZ: That was precisely the word I used. So I went, "I gotta protect my director." The movie Marc is making is really good, and it deserves a fresh approach. And I felt when I saw this trailer that this is the first thing that goes out, this is how we're going to say hello to the world? No, we can't do that. So I suppose I shot myself in the foot.

MW: Now he has to score the trailer.

HZ: But at the same time, it's interesting.

MW: It's a good experiment. Also what you did — if it sucked, we just wouldn't have used it. But it's really, really good.

HZ: There are many people who need convincing. New is good. New doesn't necessarily have to be good, but we're trying!

MW: I'm not worried about it. I think we're fine. I think we just need to make little tweaks and they'll be won over. I think they are already, really.

HZ: Well, I know [Sony Pictures studio chief] Amy [Pascal] likes it.

MW: Does she? Oh, good.

HZ: She understood what the problem was straightaway.

MW: What, using Dark Knight music in a Spider-Man trailer?

HZ: OK, you're being a little more candid then I would be. But I'm going, Guys, that was five years ago! Please!

MW: It wasn't literally Dark Knight music.

HZ: It was the other problem. It was the cheap knockoff. It was the McDonald's version.

MW: We're trying to do something much more funk-based. Much more contemporary coloring.

Since Webb's early, he contents himself with puttering around Zimmer's studio as we finish the interview, discussing how Zimmer leaned heavily on both his considerable musical faculties and his gorgeous music facility to craft the score for the powerful images in 12 Years a Slave. "The one thing I didn't want to do is write period music," he says. "I wanted to write timeless music, and be a secret little bridge into right now. I think what a movie can do at its best is start to provoke a conversation you've never had before. I thought, if I can just be a way of opening the doors into that conversation — I don't ever like music to tell you what to feel, but I think music gives you a signal that you're allowed to go immerse yourself and feel something."

Finally, as Zimmer sits at his desk for a few quick photographs, Webb sits at the piano and begins to play. He's actually pretty good — whatever piano lessons Webb took in the past, they've definitely stuck. Zimmer smiles. He can't help himself. He turns to his computer, dials up some orchestra samples, and stars playing along with Webb, shifting along with him from classical chamber music to "Lean on Me" to what sounds like a random musical doodle. Eventually, Webb turns to Zimmer and asks about one of the earliest themes he ever wrote.

"How do you do True Romance?" asks the director.

"Oh!" says Zimmer, leaving the safety of his computers to sit at the piano he thinks he's not worthy to play. "It's really simple," he says, sitting next to Webb. "But it took me forever to figure out how to make it really simple."