The birth of modern humanity has just been put back by about 100,000 years, according to a study, suggesting that the rise of Homo sapiens was a slower, more complicated process than previously thought.

Until now, the oldest confirmed fossils of modern humans were some 195,000-year-old remains found in Omo Kibish, Ethiopia.

But scientists working at a site in Jebel Irhoud, Morocco, have found several new Homo sapiens fossils, which they have dated to between 300,000 and 350,000 years old. The research is published in the journal Nature.

"I think it’s a big discovery," Shannon McPherron, an archaeologist at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology, in Leipzig, Germany, and one of the authors of the study, told BuzzFeed News. "It's Homo sapiens, it's us, and it tells a new story about our dispersal around Africa."

Martin Bates, a geoarchaeologist at the University of Wales Trinity St David, who was not involved in the study, told BuzzFeed News: "It's a very interesting paper. The dating is very comprehensive – they've done everything by the book."

The Jebel Irhoud site has been known for some time. In the 1960s, the fossils of ancient humans – two partial skulls and a jawbone, or mandible – were found there.

But the dating mechanism used – a procedure called "electron spin resonance" (ESR) – tentatively put the age of the remains at between 90,000 and 190,000 years old. Determining a more accurate date was difficult, partly because the fossils' original position was not recorded, and partly because ESR is unreliable if you don't know the local conditions.

McPherron and the Max Planck team went to Morocco to see if they could get a more accurate date. "We were hoping we’d find something in our own excavations," said McPherron, "because we didn’t know where the old stuff came from." To their excitement, they found a crushed skull and a nearly complete jawbone, and were able to say with some accuracy where it lay in the excavation.

"We were lucky," says McPherron. "It was a really well-preserved mandible. So we could do a lot of dating."

They used flints, which were found in large numbers around the bones, for dating, using a technique known as "thermoluminescence". When flint is heated in a fire electrons are trapped within it. Over time those electrons escape. If you know the rate they escape at, you can work out how long it's been since the flint was heated. "There were lots of flints and the hominins had the use of fire," said McPherron, "so there was lots we could use."

The team came up with a best estimate of 300,000 years old.

"This is a dramatic finding, and it makes sense given what we know already," Iain Morley, a professor of palaeolithic archaeology at the University of Oxford, who was not involved in the study, told BuzzFeed News. "The Ethiopian fossils from 195,000 years ago are very, very conspicuously modern-looking," he said. That's strange, he said, because you'd expect to find some more intermediate fossils, between older species of humans and completely modern ones.

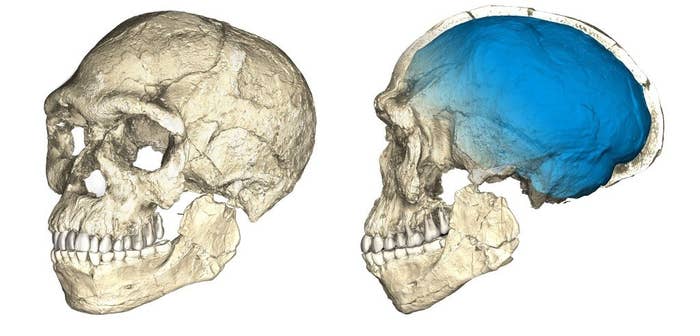

And the previously found Morocco fossils, said McPherron, were oddly archaic, with a broad face like ours but a more elongated cranium.

The view used to be that modern humans emerged rather suddenly about 200,000 years ago, but recently it's thought to have been a slower, more gradual process of physiological and behavioural change, and this paper fits in with that. "[The findings] show a big difference in time," said Morley. "It’s not 200,000 to 220,000, it’s 200,000 to 300,000. It’s 50% older. But it doesn't contradict what's already known. There's nothing out there that, if this is true, [now] can't be true."

Bates said that the fossil record is so patchy that any major new find like this is likely to change the state of the field. "These sorts of sites – with good-quality fossils, and artefacts, and radiometric dating – are so rare," he said. "When you find one, you're almost certain to find something unprecedented. It's like looking at a jigsaw puzzle when you only have five pieces." He said that this could send archaeologists back to lots of other previously investigated sites to see if they can find new things.

The find makes sense of some behavioural changes that were happening around this time, said McPherron. There was a switch around 300,000 years ago from big, heavy hand-axes to tools of finely chipped flint. This later period is known as the Middle Stone Age. "There was a notion that this Middle Stone Age change was to do with a biological change," said McPherron. "I think this will make people happy."

It fills in some holes in our geographical understanding of human evolution as well, he said: "It brings North Africa into the picture." Nowadays, North Africa is largely cut off from the rest of the continent by the Sahara. But at times in the past there were "green Sahara events", in which the desert became a grass plain that animals moved across, like the modern Serengeti. "It was easily traversable," said McPherron. "And there was one about 330,000 years ago. All it takes is a green Sahara event to bring North Africa into the picture. You can easily imagine people moving across to Morocco in pursuit of game."