If you've been on the tube in the last couple of days, you may have noticed something. It's REALLY HOT.

On a scale of 1 to 1000000000000 how hot will it be on the Tube today? ☀️🔥💥#Meltinginthenameofthelaw #london #lawyerlife

London was fun today - i particularly enjoyed the tube. that hot airless hole in the ground...mmmmm

This happens every year. Last August, according to Transport for London, the Bakerloo line reached over 31°C. Throughout the summer, it averaged almost 27°C. A couple of years ago the Central line hit 34.8°C. For context, European livestock laws say the maximum temperature for transporting cattle is 30°C.

And a few people have wondered: Why don't they cool it down a bit?

Why is it legal for people to travel in a tube carriage and its boiling hot. Where the hell is the AC @TfL ?? #London

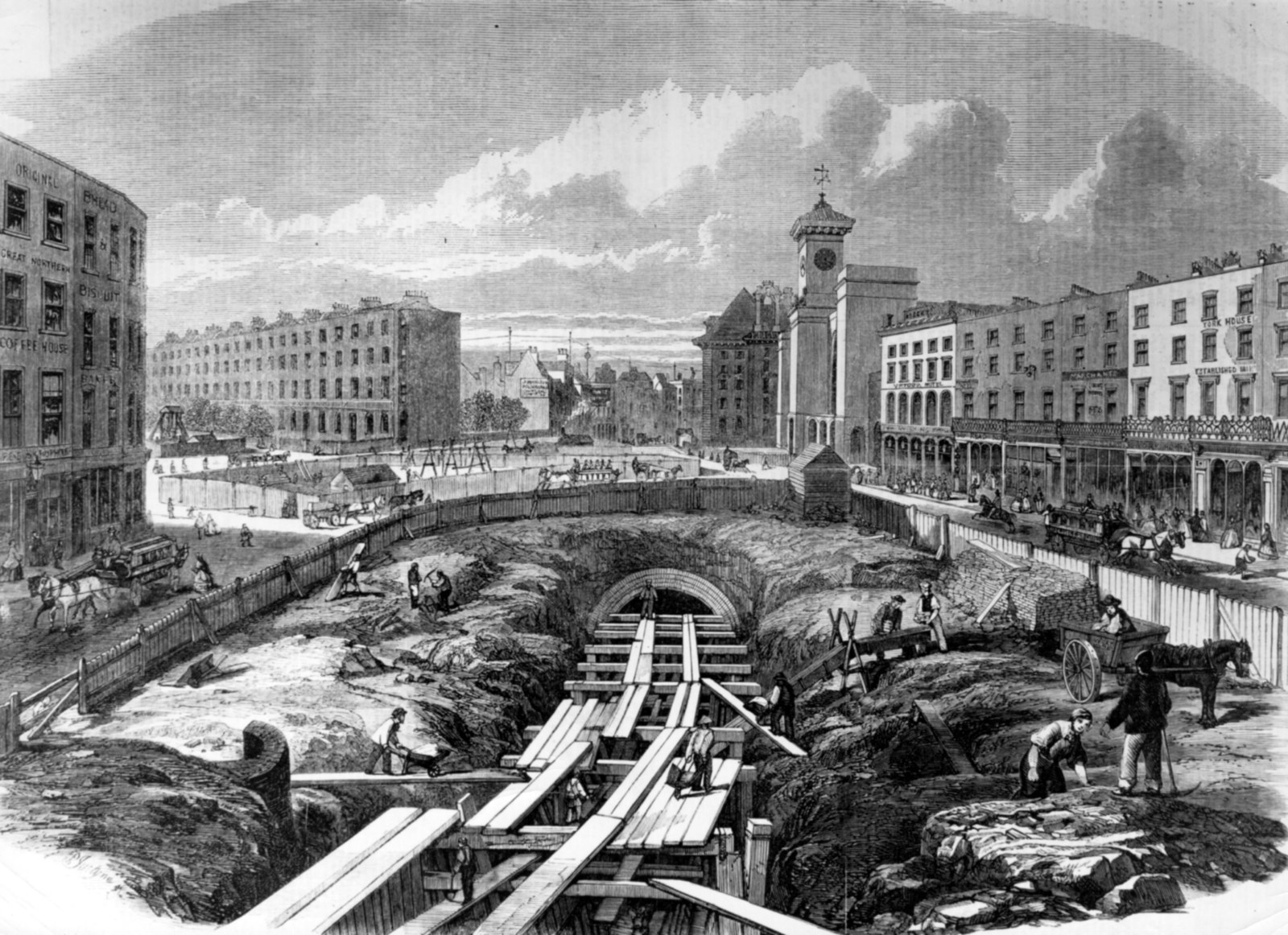

The trouble is, there are a few problems. The main one is that the tube is really, really old.

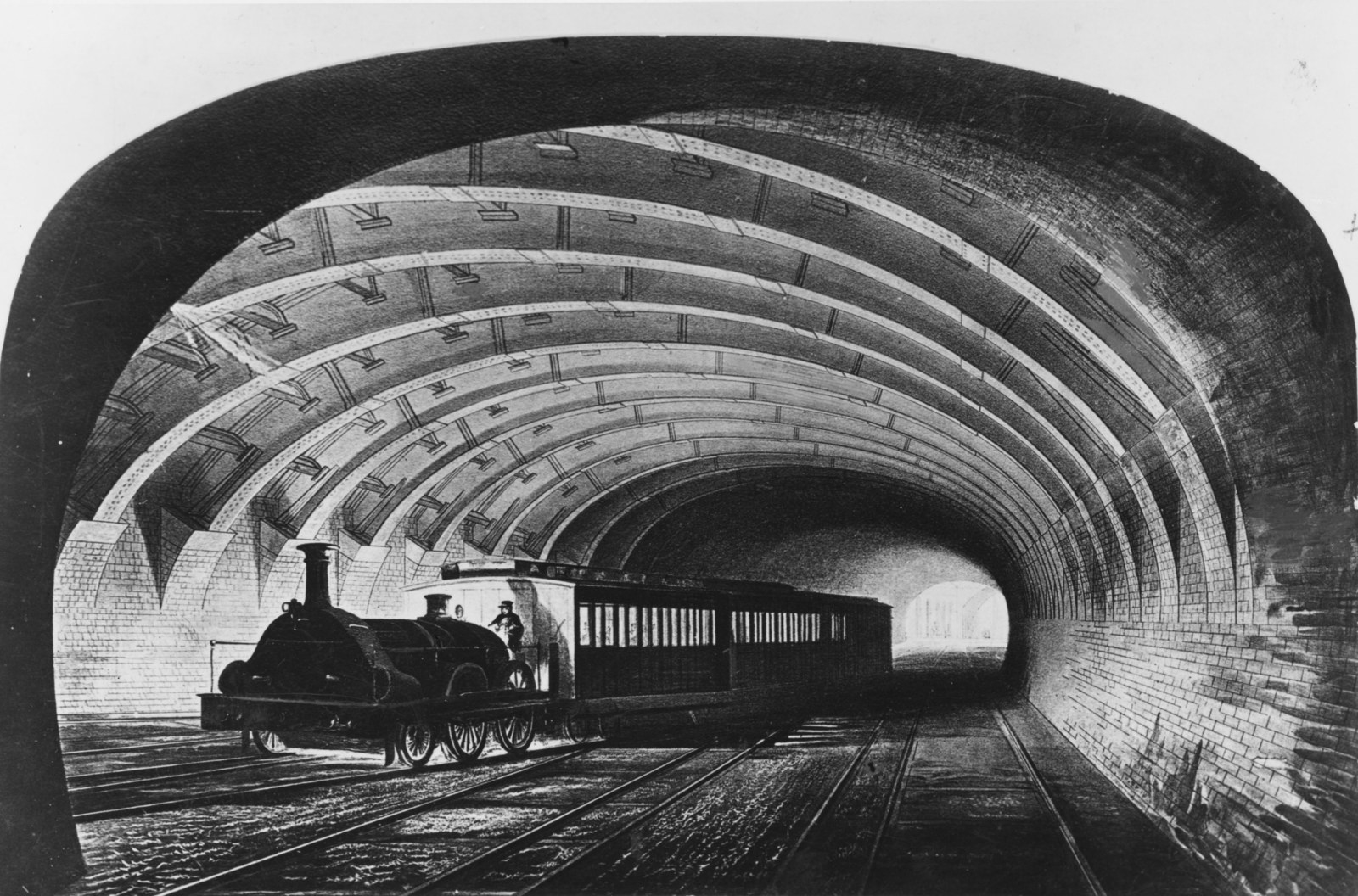

Graeme Maidment, a professor of air conditioning and refrigeration at London South Bank University, tells BuzzFeed News: "It's a system that, in places, was designed 150 years ago, for steam trains.

"It wasn't designed for the number of passengers, and the number of trains, that there are today."

That leads to a few more specific problems. One is that there's not much ventilation, so the tunnels heat up quickly.

"That's probably the most important issue," says Maidment. "The number of ventilation stacks" – surface chimneys that let the hot air out of the tube system – "is much lower than that of alternative metros [underground railways] that were designed for electric cars running at much higher densities." He estimates that the number of ventilation stacks per mile on the Hong Kong metro is about 10 times that of London.

It's a particularly tricky problem in London, because the clay that the city is built on is pretty good at keeping heat in.

"It's a good insulator," says Maidment. "Over time, there's been a buildup of heat in that clay layer." Lots and lots of heat gets released by the trains: from the engines, obviously, and the people, although actually the largest contributing factor is the brakes heating up as the trains stop at stations – this 2007 article in Plant Engineer magazine estimates the contribution of brakes at 38%. The clay just can't move the heat away fast enough. When the tunnels were built, the average temperature of the clay surroundings was 14°C. Now it's more like 25°C, and rising as more and more trains are put on the network.

Another problem is that there's not much space, so you can't really put air-con in the trains in the deeper tunnels.

"It's a physical challenge," says Maidment. The tunnels are narrow, and when you've got narrow tunnels, you need smaller trains. "These things are jam-packed with electronics, and braking and electromechanical stuff," he says. "And the trains are quite small compared to other metros."

So finding space for air conditioning units is tricky, although it's been done on some of the shallower subsurface lines, where the tunnels are bigger.

Also, even if you could install more air-con, it'd really just create new problems, because all air-con does is move the heat from one place to another.

"Air conditioning would take the heat out of the train and put it into the tunnel," says Maidment. "So the issue would be how you then dissipate it from the tunnel." And, of course, if you're running your train through a baking-hot tunnel, you have to work harder to cool it, so you'd be pumping more heat out into the tunnel, and so on. "It gets less efficient," says Maidment, "and potentially less reliable."

But that doesn't mean there's nothing that can be done. There are a few things that are being tried. One is using groundwater to cool the tunnels.

"At Green Park, there's cold water in the ground," Maidment says – specifically, the River Tyburn, an underground tributary to the Thames. Engineers already had to pump water out of the station to keep it dry; now, following the work of Maidment and his LSBU colleagues, they have run it through a heat-exchange system, so the cold water is first pumped through a cooling system. Then, after it has heated up (and taken some of the heat energy out of the station), it goes back into the river. It's cooled Green Park down by 3°C and is about three times as energy-efficient as normal air-cooling systems.

At Oxford Circus, another kind of water-cooling method is used. Water is cooled down on the roof of an adjacent building, then run through the station; after it heats up it is pumped back up to the top of the building again.

Another is simply building more ventilation shafts, although that has its limitations.

"London Underground have been working to install ventilation wherever they can," says Maidment. "More than 200 new vent shafts across London, and upgrades to existing ones." Tunnel shafts have been expanded and new, more powerful fans installed.

But obviously, buying the land for the stacks is expensive, and there are laws restricting where you can build them. So this can't be the whole solution.

There are also more ambitious experiments being tried, to put the heat from the tube to better use.

The heat from the underground is usually just pumped back out into the air. But there are efforts to capture that energy and use it to heat homes. There's an experiment, again led by Maidment alongside Islington Council and London Underground, to transfer the heat from the disused York Road station into Islington homes. There are also wider plans to look at the best places to capture energy from, on the tube and other subterranean sources such as sewers.

But it's not an easy job.

"Working on the tube is difficult and expensive," says Maidment. "It needs constant maintenance. It's not straightforward on a number of levels." It's old and built in clay and carries more than a billion people a year. So you can probably expect it to be pretty warm for the foreseeable future.

CORRECTION

All the images in this piece now show the London Underground. An earlier version of this piece showed a picture of Mount Pleasant Depot, which, as everybody knows, is on the Post Office Railway, not the Underground.