The Tory government called a snap election with just a few weeks’ notice. It was a time of national crisis; the government had a small majority, and wanted to give itself room to manoeuvre. Its campaign warned that the left-wing Labour opposition would take money from voters’ pockets. But the gamble backfired badly – the Conservatives' vote slumped, their majority vanished, and Labour was resurgent.

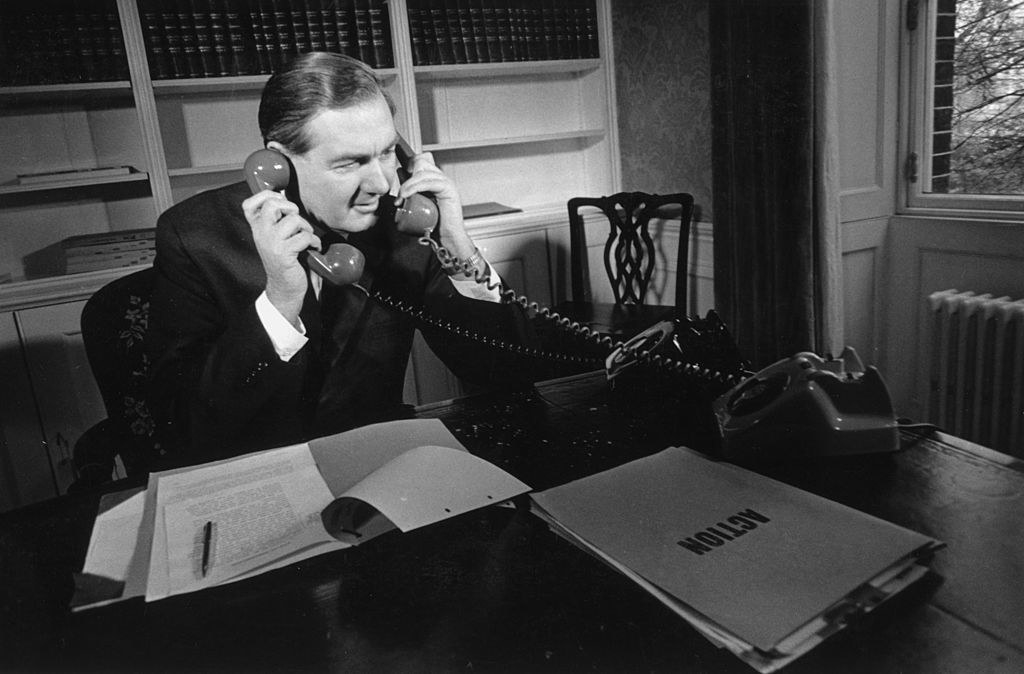

But this was not June 2017, it was February 1974; the Tory leader was Edward Heath, and his Labour opponent Harold Wilson.

Four decades before Theresa May threw away her majority in an unnecessary election, Britain went through a tumultuous few years of minority government, political uncertainty, and endless horsetrading over votes to keep the country running. The parallels between that period and the new political reality of 2017 offer a stark illustration of the difficulties of surviving as a government that can’t control the House of Commons.

At the February 1974 election, Wilson’s Labour became the largest party, although he lacked the seats to form a majority even in coalition with the Liberals. Labour tried to govern as a minority, but to no one’s surprise it couldn’t get anything very much done. A second election was soon called, in October that year, from which Labour scraped a majority of just three seats.

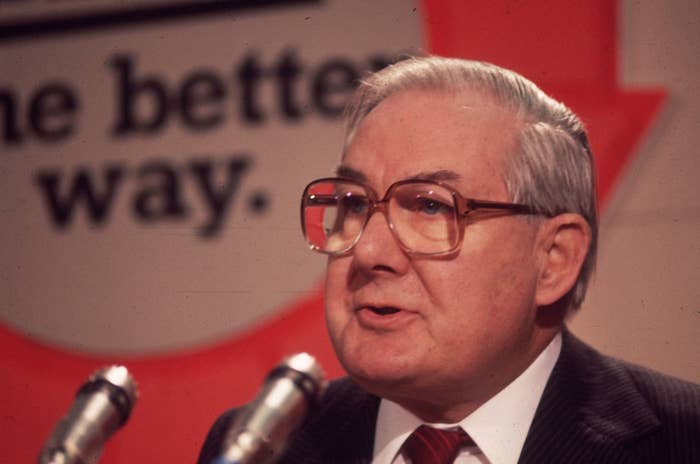

But Wilson, his health failing, was succeeded by Jim Callaghan in 1976, and the party lost a series of by-elections. The next year, with its slender majority evaporated, it faced a vote of no confidence.

Callaghan tried to create stability with a more permanent arrangement with the Liberal party, called the Lib-Lab pact. But that was very much a hand-to-mouth arrangement – the Liberal party, led by David Steel, simply agreed to vote with Labour on the no-confidence vote and any future ones.

“Wilson had had a really successful 1960s,” says Dr Charlotte Riley, a lecturer in 20th-century British history at the University of Southampton. “He was popular in the country, and reasonably popular in the parliamentary Labour party and the cabinet. Callaghan was a much more divisive figure.” And he faced a much more volatile time – inflation, an increasingly dangerous situation in Ireland, and a louder and more confident voice for Scottish devolution from the growing Scottish National Party. “There were these moments in 1978 and 1979 when Labour were really struggling,” says Riley. “They lost control.”

Just as May is relying on Northern Ireland’s Democratic Unionist Party to prop up her government, Callaghan’s Labour tried to keep doing deals with the Ulster Unionist Party and the SNP in order to get their legislation through, but it was hard.

“Devolution in Scotland took up huge amounts of parliamentary time,” says Riley. There were people in the Labour party who really believed in it, but also it was the price of doing business with the SNP.

But, Steven Fielding, a professor of political history at the University of Nottingham, says, “the problem isn’t necessarily the people you have an agreement with. It’s your own people. In politics, the enemy’s always behind you”.

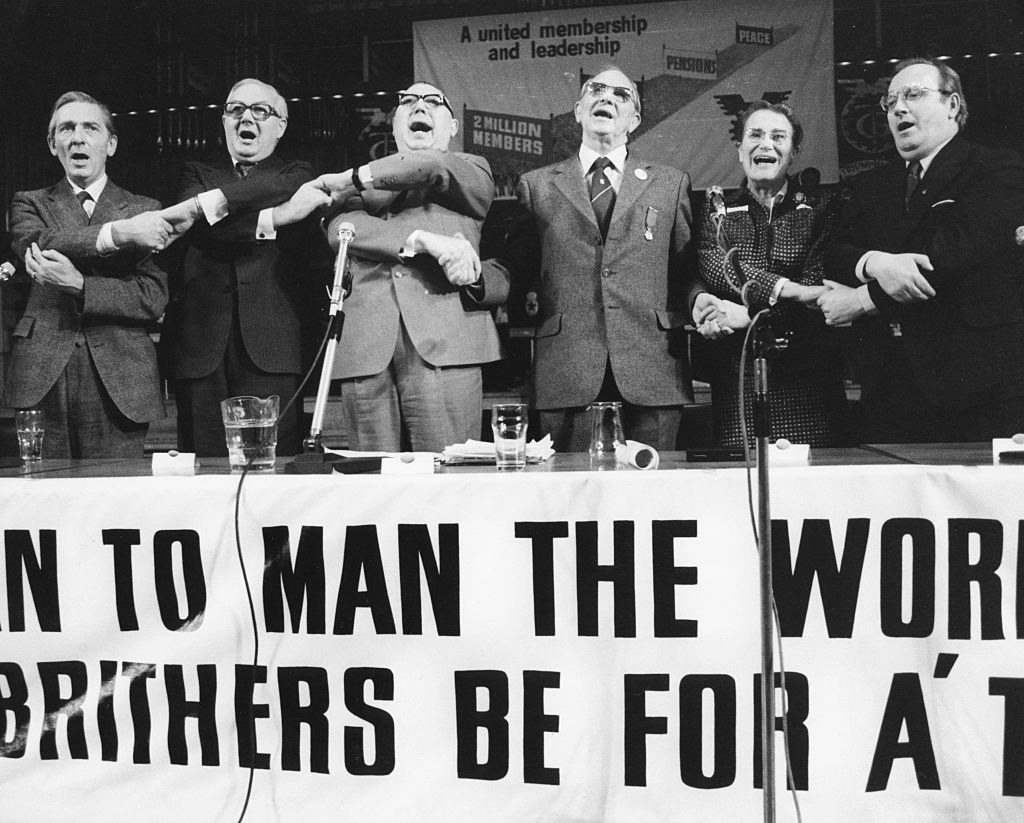

Callaghan found this out during the fire brigade strike of 1977, when several people burned to death. Labour "were trying to build this idea that they were moderating labour relations,” she says – that they were facing down their base, that they weren’t slaves to the trade unions. But without a parliamentary majority he couldn’t win the battles. The Winter of Discontent in 1978-79, when strikes were breaking out everywhere, was another apparent example of Labour’s weakness.

This has happened to the Tories more recently, too: John Major came out of the 1992 election with an unexpected majority of 22, but a long string of by-election defeats and the defection of one MP, Alan Howarth, to Labour stripped it all away. And that left Major vulnerable to attacks from his own supposed supporters. “A minority government, or a small majority, leaves you vulnerable to the rebels in your party who don’t agree with your line,” says Fielding. “It gives power to extremists, to those who are committed to a cause.” The cause – as so often with the modern Conservative party – was Europe.

Its problems were exacerbated by a resurgent, united Labour party under John Smith and later Tony Blair. “Labour was playing hardball,” says Fielding. “It would vote against policies it actually agreed on to put the government in a position that it was going to lose. If you’ve got an implacable, united opposition, plus headbangers in your own party, you’re in trouble. The initiative is out of your hands: You become dependent on others, and the whip doesn’t have much influence.”

The modern parallels are obvious, he says: The Conservatives are as divided over Europe now as they were then, and just as full of zealots. “We know that the hardline Brexiteers will do almost anything,” says Fielding. The question is if Labour can take advantage. “I don’t know whether Corbyn has the authority; maybe this campaign has given it to him. If he can, and May is held to ransom by her own hardliners, she’s in trouble.”

We’ve been talking about minority government as unstable things. But “once upon a time it was normal for no party to have a majority and coalitions were the norm, especially in the first half of the 20th century,” says Dr Andrew Blick, a lecturer in politics and contemporary history at King’s College London. “They can function.”

This was true even of Callaghan’s weary government, Riley says. “They did achieve things. Pension reform, the Sex Discrimination Act. Key health and safety legislation came in under Callaghan. There were quite a few landmark things.” They wrangled their deals through – Walter Harrison, the Labour deputy chief whip, twisting arms and making deals in back rooms to muster the votes.

The thing that matters in these cases, says Riley, is the narrative. “The reason minority governments are viewed so negatively is because, a few key times, having a minority is associated with a party that’s starting to lose power,” she says.

But it’s not always as simple as that. For instance, 1923, the Conservative leader Stanley Baldwin failed to win an election he didn’t have to take; he had a healthy majority of 74, won by his predecessor Bonar Law the previous year. “Politics was becoming more presidential,” says Dr Luke Blaxill, a political historian at the University of Cambridge. “Baldwin wanted to increase his own authority. Plus he wanted to push through some unpopular reforms, on tariffs on goods from outside the British Empire.” So Baldwin went to the country, unnecessarily, and – like May – got a hiding, losing 86 seats, mainly to the still-young Labour party and the Liberals.

The Tories were still the largest party, with Labour in second. But Baldwin was well short of a majority, and when he tried to pass a King’s Speech with the tariff reforms in it, he failed. The Labour leader, Ramsay MacDonald, was offered the chance to become the first ever Labour prime minister.

Riley uses a football analogy: If you’re 1-0 up for 89 minutes, and then concede an equaliser, it feels like a defeat. If you’re 1-0 down, and score in the last minute, it feels like a win. A once-powerful government losing its majority feels like it’s sliding towards irrelevance, but an insurgent party getting a chance at government feels like it’s on the up.

This is why the two 1974 elections felt so different, she says – why the first, while a defeat, felt like a win, and the second, though a win, ended up feeling like a defeat. Getting the chance to govern from a minority in an election is very different from winning a majority and slowly losing it, like Callaghan in the 1970s and Major in the 1990s, their majorities slowly deflating, staggering to a weary, defeated end. “We see it as a government losing relevance, or a majority getting chipped away at.”

When the end came for Callaghan, it came as a result of the deals he’d made finally running out. The Lib-Lab pact collapsed in 1978; everyone expected him to call an election, “but he couldn’t even get to that point.” says Riley. He limped on, hoping for a turnaround in the polls that would give him a chance of victory.

“Then in 1979 the Scottish devolution referendum didn’t end in devolution,” says Fielding, and the SNP lost interest in their side of the bargain. Margaret Thatcher, the new Conservative leader, called a motion of no confidence, and the SNP backed it.

Even then, he almost survived. Sir Alfred Broughton, a Labour backbencher, was dying in hospital; according to Roy Hattersley, he had offered to retire a year earlier, but Labour doubted it could defend his seat in a by-election and asked him to stay on. Usually, when he was unavailable to vote, a Tory MP would abstain, in a gentleman’s agreement.

There was a sad and noble end to the story. Broughton was desperate to come to the Commons to vote on the motion of no confidence. Callaghan refused, in the end, to let him, and Harrison, the chief whip, went to his opposite number, Bernard Weatherill, to see if a Tory would abstain. Weatherill said that on such a life-or-death matter, no one would – but rather than break his word, he said he would abstain himself. Harrison released him from his agreement. In the end, Callaghan lost by a single vote, paving the way for 18 years in the wilderness for Labour.

Theresa May will be hoping her minority government doesn’t suffer a similar fate.