This is Part 3 of a BuzzFeed News investigation.

Part 1: Revealed: The Hidden Epidemic of Abuse, Overdose, And Death Caused By The Sex Drug G

Part 2: The Lethal Sex Drug GBL Is Being Sold Through Facebook

Part 4: A Warning Has Been Issued That Rapists Are Mixing The Drug GHB With Lubricant

From afar, the long black shape lying under the trees looked like a discarded object.

As Ashley Chaplin walked closer, cutting across the lawn of Regent’s Park, the blurry image on the grass ahead sharpened. It was a person. He sped up, striding towards the body, drawn by a hunch that with each step grew into dread. A black towel was pulled over the face and torso. Its edges reached the hairline, revealing just enough.

He recognised the hair.

The next hour was horror.

Pulling back the towel, realising that it was his husband, the man he had loved for 15 years. Feeling the fridge-cold temperature of his neck, seeing the strange, concertinaed marks on his face, the liquid coming from his mouth. Phoning 999, a woman telling him how to do CPR, Chaplin performing it inexpertly, desperately, on his husband’s chest, pushing up and down, up, down, up, down, the futility never stopping him, until the paramedics arrived — one man, one woman — telling him they would take over now, that he must step back, from where, by the hedge on that Sunday afternoon, he could only watch as they gave up.

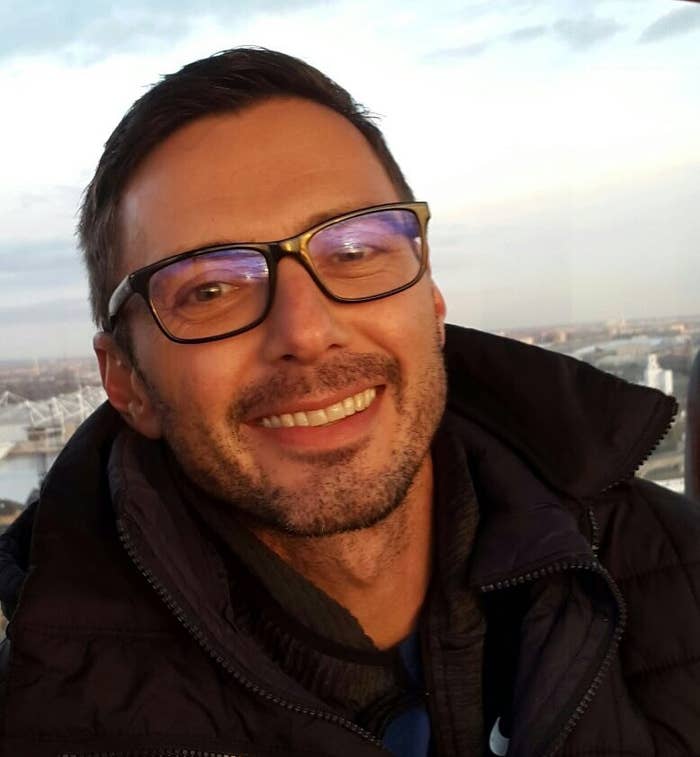

Gerhard Venter was dead, aged 39. It was September 2, 2018, a sunny lunchtime in London’s famous park. He had probably been dead for several hours, or perhaps it was the day before.

A year later, still no one knows.

The time of death would prove to be just the first question left unanswered. From the moment paramedics pronounced that his husband was gone, Chaplin faced an unending search: to uncover the causes and circumstances of Venter’s death. The truth. He hoped the police would help. But as the first anniversary of Venter’s death passes, his widower is still fighting for answers.

It took four months for Chaplin to learn which substance killed Venter: GHB, the drug commonly used with crystal methamphetamine to heighten sex between men — chemsex — and also sometimes referred to as a “date rape” drug. But Chaplin had to demand the test for GHB, weeks after his husband’s death, because it is not included in most routine toxicology screens. He fears that had he not, he would never have known.

Chaplin also does not know why police declared that the death was non-suspicious the day the body was found, without key information available, nor why that assumption was not amended either as the drug was identified or as he supplied more details to the investigating officers.

Police knew little of the dramatic sequence of events leading up to Venter’s death. There was so much more there.

Venter’s case raises key questions about how police are responding to fatalities from GHB. Following the 20% cuts to police numbers, do they have the resources to investigate fully a lethal overdose? Given that GHB is an odourless, colourless liquid easily slipped into a drink but rarely tested for in hospitals or postmortems, are they equipped with the basic medical evidence surrounding this most elusive of substances? And if taken at a chemsex party, for example — with everyone unknown to each other and all detached from reality — how could officers hope to prove that a fatal dose was intended, or who administered it? Do most officers fully understand the contexts in which GHB is taken?

Doubts keep tugging at Chaplin, forcing him to consider the worst. “I want to believe it’s suicide,” he says, sitting on a sofa in north London. “It would be easier.” He is leant over on his forearms, fingers interlocked, detached from the words. His accent is South African; his voice is soft.

"I want to believe it's suicide. It would be easier."

But such assumptions of suicide or accidental overdose from GHB have been made before, to catastrophic effect.

When three young gay men were found slumped, dead, in or around the same graveyard in Barking, east London, between 2014 and 2015, the Metropolitan police believed the lethal GHB intoxication was non-suspicious. In fact, it was the work of the serial killer Stephen Port. He went on to rape and kill again, deploying the same method: GHB overdose. Only then, and after he was convicted in 2016, did the Metropolitan police instigate training for officers about GHB and chemsex.

Following considerable criticism over its investigation, the force also reopened its files on 58 deaths from GHB over the previous four years in London to see if foul play was involved. Nearly three years later, it has not published its report. But it was finished months ago, BuzzFeed News can reveal. When approached, the Met told BuzzFeed News that “some organisational learning was identified and this is being taken forward”. The specifics of those lessons, however, were “still being collated”.

Chaplin wonders how much they have learned, how much has changed. He wonders whether Venter’s death was neither suicide nor accident but murder, and does not understand why the police would rule out the possibility. Particularly given what he told them.

Chaplin cuts back to eight months before Venter’s death, in early January 2018, the day his husband sent him a WhatsApp message. It contained the names of four men, with an instruction. “He said if he is ever killed, these are the four people I must get investigated.”

The police, he says, have never looked at the message or questioned those men.

There was cause for Venter’s fear during that last year. He had threatened the four, one in particular, telling him he would report to police what he said the man had done to him: rape. He had known the men from the furthest fringes of the chemsex scene, where, for them, meant extreme fetish combined with crystal meth and GHB/GBL — also known, respectively, as T and G.

Chaplin contacted BuzzFeed News in frustration, mounting as the months elapsed and the answers eluded him. He had seen an advert placed by BuzzFeed News in association with Channel 4’s Dispatches asking for people with experience of G to come forward to tell their story for a new documentary about the drug (called Sex, Drugs and Murder, to be broadcast this Sunday).

But Chaplin’s case, still unfolding during filming, needed to stand alone. A year on, Venter’s body is still in the morgue. Chaplin’s grieving is stalled, waiting until the secret to his husband’s death is unlocked.

They made for an unlikely couple. Although both South African, Venter hailed from a conservative Afrikaans family but was highly sexual, prone to confrontation, and a decade younger; Chaplin, now 51, was the stable, successful, strait-laced of the two. He works in financial services. Venter flitted, forever having issues with colleagues, eventually doing administration for his husband.

Venter had problems with communication and relationships, interpersonal blocks that built over the years into a wall between him and others so distinct that it could no longer be ignored.

“I stumbled across an article in the New York Times,” says Chaplin, perched on the edge of a sofa in north London, his buttoned-down shirt crisp and neat. With his greying hair and steady manner he looks unremarkable, at first.

The article was about the milder end of the autism spectrum.

“Gerhard fitted squarely into it,” says Chaplin. There was his strict need for routine, the inability to express himself, the recurring problem of retaining friends, forever alienating them with what seemed like rudeness or aggression. Chaplin broached the issue with his husband. “He almost acknowledged it, as if he knew that he did have it.” But it had not been diagnosed.

During their relationship, Venter would shut down if upset. “I could never break through and find out what was concerning him,” says Chaplin. Friendships proved impossible, so he struggled with loneliness.

“We relied on each other,” says Chaplin. They had two dachshunds that they adored. And Venter loved exercise, almost fanatically so. Although not perfect, theirs was a contented life, Chaplin thought — until 2017.

Venter said that he needed to explore sexually. “So we agreed we would have an open relationship,” says Chaplin. After more than a decade together, with an age gap, a difference in sex drives, but enduring mutual trust, it was the pragmatic choice.

Venter would tell Chaplin he was staying over at different men’s houses. No questions were asked. “That was part of the deal,” says Chaplin. What was important to Venter was feeling free, and Chaplin’s love meant respecting that — but more, seeing in this exploration a potential: that Venter might finally forge friendships that in everyday life eluded him.

“Things went fine,” he says — for the first six months. He pauses. “The problem is the fetish and extreme sex is one thing, but once you start experimenting with drugs, it takes a different course.”

Initially, from early 2017, that course was crystal methamphetamine — the rocketing stimulant used by many amid chemsex — which grips users into both intense highs and, for some, psychotic episodes or addiction. Chaplin, who has never taken anything, was unaware of either meth or GHB until it was too late.

"I could never break through and find out what was concerning him."

During that year, Venter began to make connections with a clutch of men on the chemsex scene. But towards the end of 2017, splinters formed.

“He had started to argue with a lot of them,” says Chaplin. Venter had become increasingly alarmed by the meth and the G and the damage it was doing to him. The illegality, for someone obsessed with rules, disturbed him too — and so he wanted to stop taking them.

Venter sought help from London Friend, an LGBT health charity that offers counselling and support for drug problems. But everything was to become darker.

“He accused somebody of raping him,” says Chaplin. The accused was known to him, one of the four men he would name in the WhatsApp message, who all knew each other. “He said he recalls going to this person’s house and only has a memory up to a certain point,” says Chaplin. “Until the next morning, where he woke up. He said he felt pain in his backside … as if there had been quite active sex, in other words. He had no memory of sexual intercourse.”

Experiences of sexual violence while on GHB are common. More than 1 in 5 gay men who responded to a survey that BuzzFeed News and Dispatches conducted for the documentary — the largest of its kind — said they had been subjected to rape or sexual assault while on G, which frequently renders users unconscious.

But it was not until January 2018 that Chaplin knew about the rape allegation, or anything about the drugs. Venter came home “extremely agitated, pupils dilated, and he was just ripping everything up…breaking everything. He was looking for microphones”.

Venter had become paranoid, prompted partly by the meth, but also, Chaplin now thinks, by the assault and the breakdown in the friendships.

Later that January, Venter went downstairs one night to their little home gym.

“I just heard this loud bang,” says Chaplin, his face frozen suddenly, eyes staring. “Our little dachshund rushed up the stairs and was screaming and dancing around the place. I went to see what was going on.” He stops and breathes in.

“Venter had hung himself. There is a pull-up bar, so he had hung himself on that, but the machine had fallen over and hit the other side of the wall.” Chaplin arrived just in time. “He was convulsing. I rushed in and lifted him off the ground to take the pressure off his neck.” With this, Venter became conscious, so Chaplin helped him up and guided him to bed.

They agreed the next morning that Venter would take a week off work. It was during this week that he finally opened up to his husband about his fears surrounding the rape, and the wider behaviour of his friendship group from the chemsex scene.

“These people had started bullying him and started effectively playing with his mind,” says Chaplin. “What he was saying was that the people he had fallen out with were encouraging him to kill himself.” Venter also confided to Chaplin that on one occasion he had been admitted to hospital after losing consciousness — overdosing — again common with GHB.

And it is here that three possible explanations for his later death form, each leading up parallel paths:

Path one is the scenario Venter was trying to convey to Chaplin, that these men had the worst intentions and that ultimately they (or perhaps just one man) enacted them: murder, perhaps to shut him up.

Path two: Venter was growing increasingly paranoid, perhaps psychotic, and that spiralled, fear swelling unbearably until he could no longer tolerate it, and he deliberately overdosed himself.

Path three: These men did bully him, one of whom did rape him, but either did not directly kill him, perhaps goading him to do it, or had nothing to do with it.

Chaplin keeps an open mind. “I can only go on what Venter told me and I’ve got to balance his interpretation of things,” he says — balance it with the fact that Venter was not well. He repeats that he hopes it was suicide. “It would be a far better alternative,” he says. “But there are too many other things that need to be explained.”

What is certain is the effect Venter’s fears were having in the last few months of his life. He started believing that these men were “going to do everything they could to get him thrown out of the country,” says Chaplin. Such fear broke into paranoia with florid delusions. “He would be insistent that these people were behind the walls, under the bed.”

But again, Chaplin worries, that while part of it was mental illness, he could still have been in danger after Venter confronted the man he believed raped him: “He directly accused this individual and had verbally spoken about it to other people.”

Venter wanted to go to the police to accuse the man of rape, but Chaplin tried to dissuade him. He conveys the conversation with Venter at the time: “Can you just picture the scene, you going to a police station, reporting this…and saying, ‘I do drugs, get involved in the chemsex scene, I think somebody raped me’. You genuinely believe that anybody is going to take you seriously?”

Chaplin feared too that his husband could then be investigated for drugs offences. (The Metropolitan police told BuzzFeed News that it would always prioritise sexual offences but would not rule out investigating drug offences in a report of rape.) Venter did not report it. Instead, says Chaplin, “he blamed me for not allowing him to go.”

Venter tried to leave the chemsex scene, tried to keep away from those men and drugs — not always successfully — and in April 2018, struck up a bond with a man we will call Tim. It seemed the bond was mostly sex, some friendship, and on Tim’s part, romance; but Chaplin was not concerned. And by the summer, things had shifted for the better, he thought.

"We came to a point where we accepted each other. I understood him for the first time possibly."

“We came to a point where we accepted each other. I understood him for the first time possibly.” The cruelty of losing him so soon afterwards is, he says, the saddest part of all.

In an attempt to find other ways of connecting with people and avoiding chemsex, Venter took up rock climbing and started attending a climbing centre in Finsbury Park, north London. In his final few days, he messaged Tim to say they could no longer see each other.

The last time Chaplin saw Venter alive was the morning of Saturday, September 1, 2018. Venter said he was going abseiling with his rock climbing friends and asked if Chaplin would meet him afterwards.

“But before he closed the door, I saw on his face it was very angry — and commented on that, but he didn’t respond. He just looked at me and closed the door.”

As promised, later that morning, Venter texted his husband, asking to meet him at King’s Cross at 11am. “Everything seemed normal,” says Chaplin, who arrived as agreed and waited. When Venter didn’t, Chaplin texted and tried calling. No answer.

While waiting, he spotted two earlier texts from Venter, sent before he left, which would explain his furious expression. “The first was [saying] that he is really angry with me for not allowing him to report all these people,” says Chaplin. “That now they think he’s crazy.” The second was saying that while he likes the UK, “he can’t take these people anymore and is going back to South Africa”. Chaplin replied that they should talk about it that night. But Venter would not answer.

Unable to reach him, Chaplin started walking to Regent’s Park, one of their favourite places, where perhaps Venter had gone instead. Nothing. And still no answer on his mobile. Hours passed. He gave up and went home, wondering whether in fact his husband meant 11pm. “Bit of a long shot,” he says, but there were no other explanations.

Once 11pm came, and still with no message from Venter, Chaplin went looking for him. He walked around Finsbury Park and the climbing centre before heading home again, resolved to resume the search early in the morning.

At 5am, Chaplin awoke, checked his phone, and realised he had missed an email from Venter, sent the previous day. The heading in the subject line contained one word: PASSWORD.

It was for his iPad, sent at 1:30pm the day before, when Chaplin was walking around Regent’s Park looking for him. Chaplin entered the password and searched on the iPad for the contact details of Tim, Venter’s recent fling.

“He might know where he is,” says Chaplin.

He was right.

Chaplin texted him. A discussion ensued culminating in Tim forwarding to Chaplin what Venter had sent him the previous day: coordinates and a GPS location — a map with a pin pointing to an area in Regent’s Park, with nothing else. Venter had sent it around the time he sent Chaplin the email with his password.

Chaplin jumped on a train. Before he reached the park’s perimeter, Tim sent a final message.

“He said he is very sorry for me,” says Chaplin. He thinks now that Tim understood the GPS location picture — then combined with the fact he was missing — as a message from Venter: that this was where to find his body, that he sent it before killing himself.

Chaplin sees the logic in this but wonders how someone could take a fatal overdose on a Saturday afternoon in Regent’s Park and not be discovered for 24 hours.

At the time, he headed towards the GPS location, eyes scanning everywhere, until the black object loomed. He peeled the towel back and removed his bag from under him. “I knew that Venter was dead,” says Chaplin. But after calling 999 and performing the chest compressions anyway, he flagged down the ambulance. “I wasn’t in tears or hysterical, I was just stunned. Dazed.”

The police arrived soon after. He watched from the grass as they erected barriers around the body. They confiscated Chaplin’s phone, Venter’s iPad, his belongings and, Chaplin says, they moved the body. He cannot understand why in a sudden-death situation police would transgress the most obvious rule: move nothing.

They then brought Chaplin to the Belgravia Police Station for questioning and later that day declared that it was a non-suspicious, unexplained death.

In part, Chaplin thinks, because they found on Venter’s phone what they took to be a suicide note. But a year on, Chaplin has never been given this, nor shown it. “I have asked repeatedly, ‘Can you at least give me a transcript of what is on Venter’s phone?’ but they haven’t given me anything.”

Worse, he thinks, is that the nonsuspicious categorisation that ruled out murder without considering the rape allegation meant that the entire ensuing investigation was inhibited. It meant that a junior officer — a detective constable — was put in charge of the case and that, for Chaplin, multiple leads went unexplored.

In particular, the WhatsApp message with the names of four men. With his phone still with police, Chaplin says he informed them where to find the message, to then be able to question them. But he says the police have never done this, therefore not even speaking to the man whom his husband says raped him, and whom he threatened with police action, because police are not considering murder an option.

“I must keep open the possibility that it was purely suicide,” says Chaplin, who wishes only that the police keep open the alternatives.

Indeed, Venter sent others messages the day before his body was found, it transpired: to Tim, saying he would “see him on the other side” and to his counsellor, thanking him — something that could be seen as a final indication of intent.

But Chaplin worries; at the same time, there are things that “indicate that there is at least a possibility of it not being suicide”.

How, he wonders, did Venter switch from arranging to meet Chaplin to suddenly disappearing, buying G, and deciding to take his life? What happened in the 24 hours between messaging Tim his location and Chaplin discovering his body? He even wonders if Venter sent the messages to Tim, the counsellor, and to himself, or if it was someone else.

The marks on his body also do not make sense, Chaplin thinks, particularly combined with the neat way in which the towel was pulled over his face. “There were signs of a struggle,” he says, citing a cut like a “clean tear” on his arm, a swollen hand with “abrasion marks”, a swollen right eye, marks on his knuckles, a wound on his wrist, multiple “indentations” on the back of his arms, “similar to somebody falling backwards onto gravel”. Did he overdose somewhere else, Chaplin wonders? Was he dragged into the park?

There was grass in his mouth too, at the scene, which Chaplin finds strange, as a G overdose knocks people out — coma, not frenzy.

The crime scene manager reported that the body also had “bite marks consistent with a wild animal”, but Chaplin is baffled by this because when he asked to see the forensic photographs, there were no marks that looked like the bites of any animal in a London park. He checked afterwards.

Only when Venter’s statement arrived in the post did Chaplin learn that his husband had bought several items at the time of sending those last emails, including a box of chocolates — something the gym addict would not normally eat — and a withdrawal of £100 in cash, “which now appears to be missing”. Why, he wonders, would he need cash if he were intending to kill himself? The GHB would cost a fraction of that.

"I still talk to him. I just say I hope he's happy. That hopefully one day I'll see him again."

And only after visiting Venter’s drug counsellor weeks after his death, who informed Chaplin about GHB, did he know of the drug’s existence and then request his husband’s body be screened accordingly. “They hadn’t tested for it,” he says.

In late December 2018, nearly four months after losing his husband, he wrote to the coroner’s office, begging for the report into Venter’s death. “I couldn’t spend Christmas not knowing,” he says, referring to the cause of death. He had still not been able to inform Venter’s family back in South Africa how their son died. “I couldn’t tell them anything,” he says. A few days before Christmas, Chaplin received the email telling him GHB killed his husband. At least knowing this was a relief, he says.

But still he could not be sure who administered it. “He did fear for his life,” says Chaplin, aware also of the paranoia that had overcome Venter.

“I eventually wrote to the investigating officer,” he says — and asked to meet with him or his supervisor. The officer replied, saying it was not possible, says Chaplin. “He didn’t give a reason.” In January 2019, he filed a complaint to the IOPC, the Independent Office for Police Conduct, whose own investigation will not commence until after the inquest.

A pre-inquest review (PIR), which determines how the main inquest will proceed, took place in May 2019, with the full inquest set for early November, 14 months after Venter’s death.

But even the inquest is subject to the parameters of all inquests: to ascertain when, where, and how the person died, and only sometimes, in which circumstances. Even if the conclusion is that it was neither suicide nor accident, it is not a trial to decide who committed that killing.

This all stems from the police’s decision to rule out murder immediately, says Chaplin. “It’s very disappointing,” he says, with careful understatement. “I understand police resources [are limited]; what saddens me is, right from the outset, the case was relegated to the lowest level.” The officer who concluded it was non-suspicious will not be attending the inquest, Chaplin learned yesterday.

The funeral is still months away at best, most likely next year. Even then, Chaplin is left with a final dilemma. Does he invite the only friends Venter was able to make?

“The people that I would be inviting — potentially — are possibly the people that caused his death,” he says.

He stands up to say goodbye, but there’s something else. “I still talk to him,” he says, quietly. “I just say I hope he’s happy. That hopefully one day I will see him again.” Chaplin inhales sharply, as if bringing himself back to the task at hand.

He wants to prevent others from enduring this desperate search for answers. He says he thought British police were the best in the world. Now he wonders how many more could awake to this nightmare, with a silent killer, often not tested for and easily slipped into drinks, taking lives while leaving few clues.

When approached by BuzzFeed News with detailed points surrounding this case, the Metropolitan Police did not respond to them. Instead a spokesperson sent what appears to be a template response containing the line: “Chemsex is a lifestyle choice.” There is no evidence sex was the setting for Venter’s death itself. The phrase “lifestyle choice” has been used as a judgement on gay people for decades.

Chaplin, meanwhile, needs peace.

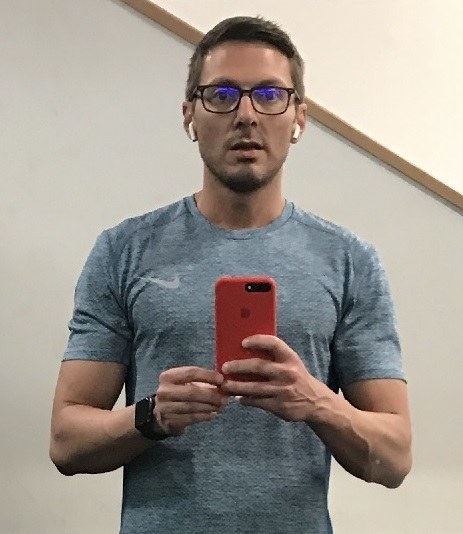

“It lives with me every day,” he says. “Every day, waking up frustrated, the multiple alternatives of what all of this could mean.” He gazes at the laptop in front of him, open on the blog he set up to write about it all. There’s a photograph of Venter wearing gym gear, taking a selfie in the mirror. His eyes are slightly widened, his mouth just open. The effect is subtle but noticeable: alarm.

“My worst fear,” says Chaplin, “is that we are never going to find out the truth.”