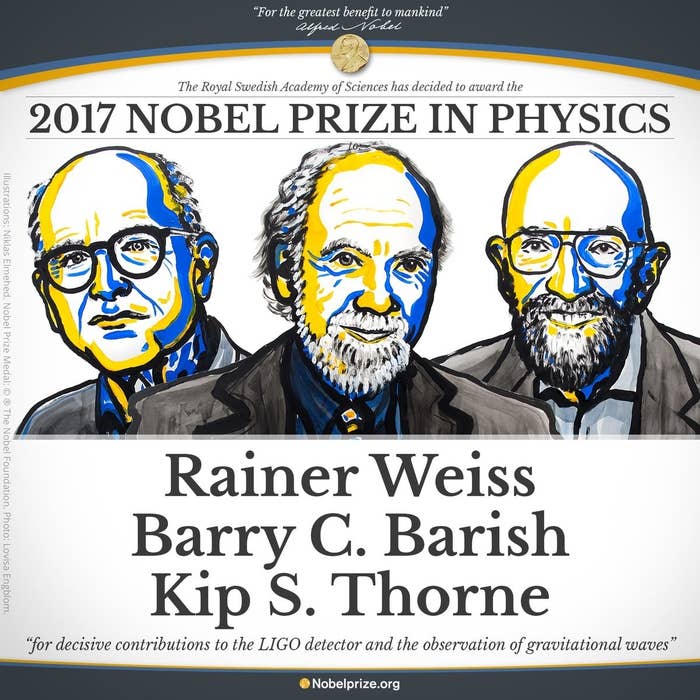

The 2017 Nobel Prize in physics has been awarded to Rainer Weiss, Barry Barish, and Kip Thorne for work that led to the discovery of ripples in space-time called gravitational waves. Weiss was awarded half the prize, with Barish and Thorne splitting the other half between them.

All three are members of the LIGO-Virgo collaboration, a team of over a thousand scientists who in February last year announced they had seen gravitational waves for the first time. Since then, three other detections of gravitational waves have been confirmed, the latest coming just last week.

Weiss told a press conference over the phone that the news was "really wonderful", but that he viewed it as something that was recognising the work of a thousand people over nearly 40 years.

"Back in September 2015, many of us didn't believe it," said Reiss. It took two months to really convince each other they'd truly seen a gravitational wave, he says.

Gravitational waves are created when two black holes merge. When a gravitational wave passes through space, space itself is seen to briefly stretch, then return to normal. The ripples in space-time were first predicted by Albert Einstein in 1919.

The waves came from a collision between two black holes. It took 1.3 billion years for the waves to arrive at the L… https://t.co/5xXbwHGr1B

The first detection of gravitational waves came on 14 September 2015. The signal was first seen in the Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory, or LIGO, detector in Livingston, Louisiana. Just seven milliseconds later, the same signal was seen in LIGO’s second detector in Hanford, Washington.

The merging black holes that created the signal have masses equal to 29 and 36 suns respectively and are around 1.3 billion light years away.

Graham Woan, a professor of astrophysics at the University of Glasgow who works on the LIGO detectors, told BuzzFeed News he thinks the prize is a “fantastic thing”.

“We’re not surprised, we were the frontrunners, and I like the choice [of the three individual winners],” he said.

“It's easy to think that with such a huge joint effort that there aren't any particular people who are crucial, but it's not true. There are individuals who made pivotal contributions to the history of LIGO and these three are the remaining ones, I suppose, who can wear that hat.”

"They really represent the three corners of success of LIGO,” he added.

"Weiss was the guy who really first understood the fundamental things about how to develop an instrument which has the sensitivity you need to detect gravitational waves," said Woan.

"Kip Thorne is Kip Thorne. If there was any individual who brings together all the things that it took to make LIGO it's probably him, both theory and designing the instrument.”

Barish ”really made the collaboration work” thanks to his experience of large particle physics projects, says Woan. “Without him LIGO would have failed – when he was brought in, he really turned it from a group of very strong-minded scientists into a proper project. So he represents the other tripod leg to make it work."

James Hough, a professor of physics and astronomy at Glasgow who also worked on LIGO, told BuzzFeed News: "It's fantastic news, very well deserved.

“The whole field will be getting enormous pleasure out of this. Everyone will be delighted that it's gone to them. We wouldn't be doing the work we're doing if it wasn't for each of these three; we wouldn't be in this position, they were totally essential. There'll be no resentment, everyone will be absolutely delighted."

"The one who hasn't got the prize is Ron Drever, who died earlier this year,” said Woan. “It’s real shame, who knows if he’d have won it.”

Drever, a professor emeritus at the California Institute of Technology, worked with Weiss in setting up the LIGO project. He was born in Scotland in 1931, and completed his PhD at the University of Glasgow in 1959. He died in March, at the age of 85, having lived to see LIGO announce its first two detections. The Nobel Prize is never awarded posthumously.

Woan said that when it comes to detecting gravitational waves, “It still feels like Christmas. We had this 50-year wait for the presents to come, and right now it still feels like we're opening the presents. The excitement hasn't dropped away yet. We're still tired and excited, like Christmas morning."

The LIGO collaboration is now heading into its third observing run. “We hope to see a number of these binary black hole systems, maybe 8 to 10 times as many, because it's more sensitive now,” he says. “So there's a lot to come."

"It's absolutely clear that we have an astronomical tool," Hough said. "It wasn't just a flash in the pan."