In the year since Britain voted to leave the European Union, we've heard a lot about how British scientists feel and what they think will happen to UK science in the wake of Brexit. But what's the view from the other side? BuzzFeed News asked scientists working in EU countries outside the UK what they think about Brexit, and what message they have for the UK science community:

Christopher Kyba, postdoctoral researcher at the German Research Centre for Geoscience:

“At probably every reasonably sized scientific meeting I've been to in the last year, Brexit has come up. It is frequently discussed in more informal scientific settings, and European researchers think it will be bad for Europe and particularly self-destructive for England. As a Canadian who has been a migrant worker for the last 17 years (eight years in the USA and nearly nine in Germany), I am personally very disappointed by Brexit, and its implicit rejection of workers like me and mixed-nationality families like my own.”

Paul Franks, professor of genetic epidemiology at Lund University, Sweden:

"The EU has been the major source of funding for many people working in my field (precision medicine), so it’s not surprising there’s anxiety amongst UK scientists about the future. However, these are smart people and they’re likely to find work-arounds that are good for the UK and good for the EU. For example, I imagine UK scientists will be welcomed with open arms into adjunct appointments at EU academic institutions. In this situation, EU money may remain fairly accessible for the UK investigators through collaborative projects – a win-win. The downside will be that grants co-led by UK scientists will be held at EU institutions, so the UK institutions will stand to lose out (on overheads and prestige), even if their scientists remain at the centre of the projects."

Elvira Fortunato, professor of materials science at the New University of Lisbon, Portugal:

“Science and technology are the pillars of the development of any society. It is important to show society that investing in science is exactly that – it is an investment in the future so that everyone, and not only someone, can live in a better world. It is also important to highlight that scientific research is not owned by some but by everyone and is for everyone. Any barrier to science is an added limitation to world development.”

Dan Andree, Swedish Innovation Agency, Stockholm, Sweden:

”In research and innovation, there are only losers with Brexit. There is an uncertainty in Europe today about what will happen to cooperation with the UK after Brexit. The UK science community should ‘use’ the uncertainty to step up contact and cooperation with their main partners in Europe. The science community should show that we cannot accept the consequences of Brexit.”

Nicole Boivin, director of the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History, Jena, Germany:

"Science thrives on the free circulation of knowledge, technology, and researchers, so Brexit is bad news for science across Europe. Pan-European scientific research and coordination make science more efficient, integrated, and synergistic, thus whatever happens with Brexit, scientists should push for continued collaboration and coordination. I really hope that scientists everywhere will press hard for sensible decisions about Britain’s scientific future, about the free flow of researchers, and about continued scientific collaboration with Europe. With what is going on in the UK and in Trump’s America, it is more important than ever for all scientists to advocate for pro-science policies."

Nønne Prisle, associate professor in atmospheric research at the University of Oulu, Finland:

"I have several good colleagues in the UK doing really exciting work in my field and will not hesitate to continue research collaborations or initiate new ones in the future. However, I am concerned about the long-term effects of an increased administrative burden in maintaining collaborations through international researcher exchange to the UK, and the continued availability of funding instruments. Pressed for time and resources, researchers may in the long run be inclined towards the more readily accessible routes. Research exchange has been vital to my own work throughout my career and I see it as fundamental for maintaining a cutting-edge research community on any scale."

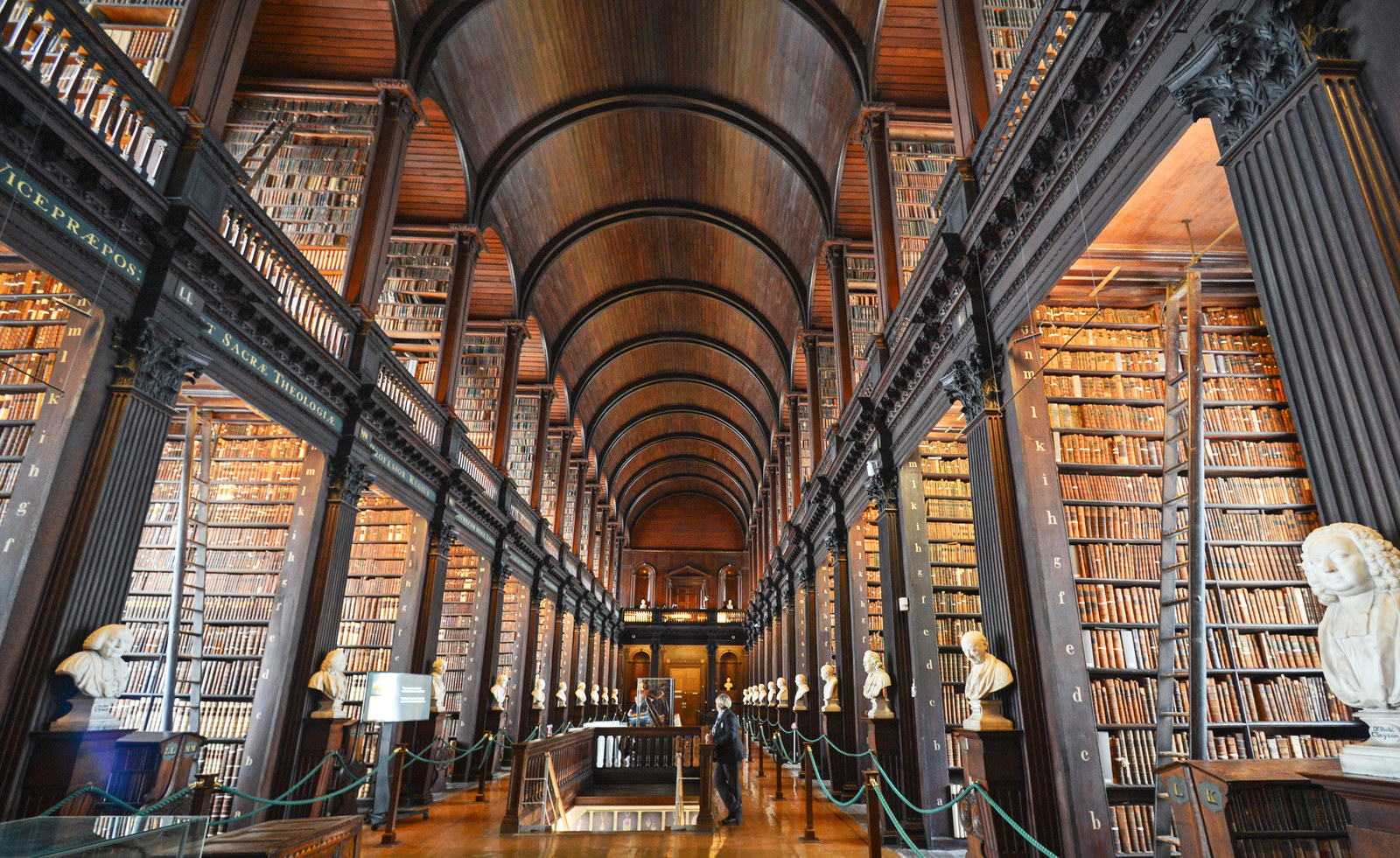

Stephen Maher, assistant professor in translational oncology at Trinity College Dublin:

“Having returned to Ireland nine months ago from the UK, I feel a certain relief when I see the state of government regarding Brexit. The majority of British research intensive universities have dropped in standing in the recently released 2018 QS world rankings, a reflection of the economic cuts to research funding, and this drop will likely continue sliding with Brexit and restrictive immigration controls. I feel anguish for my British colleagues and collaborators, and hope that somehow Brexit won’t come to pass. The people may have spoken, but the people have the right to change their minds too.”

Olivier Berné, research scientist at the Research Institute in Astrophysics and Planetology, Toulouse, France:

"I know that many of my colleagues in the UK see Brexit as extremely bad for science, which is probably true. But I would like to address a message of hope to them. 'Science has no borders,' said Pasteur, and Brexit will not stop the flow of scientific ideas across the channel. Today, in times of alternative facts, climate scepticism, and populisms which take us a step backwards, we *must* continue our common effort to understand and explain how the world works."