During the 2010 general election the Conservatives were praised for their impressive and innovative online campaign tactics. They offered daily video campaign updates on the Conservative leader via the WebCameron service, beat Labour in terms of rapid rebuttal on Twitter, and even crowdsourced a policy document via a free-for-all collective editing process. Journalists fawned over their innovative campaign tactics.

The problem was, people involved at the time remarked, it didn't win them many votes.

Since then, UK politics has developed a strange and not entirely committed relationship with the internet, with news cycles driven by Twitter outrage while the focus of press officers remains overwhelmingly on getting the right stories placed in the right newspapers. There's repeated talk of a "social media election" bringing new levels of "engagement", but this often goes little beyond sticking some press releases on Twitter and hoping it will miraculously bring 18-year-olds flooding to the polls.

With that in mind, BuzzFeed News talked to the people involved in the campaign at every level from national party HQs to local constituencies to discover how they were actually using the internet. Most were unwilling to be quoted this side of the election but – despite different opinions – several common themes were mentioned time and time again about the reality of what a "social media election" campaign actually means.

Twitter was seen as important for journalists but not for winning over swing voters.

One thing brought up time and time again by party campaigners – whose job is getting people to vote rather than winning the national media war – was a certain despair about most politicians' obsession with Twitter, which some believe encourages endless back-and-forth arguments with a small number of users about detailed policy debates rather than doing anything to win floating voters.

It's revolutionised political journalism and sped up the news cycle ("We used to have to wait until the six o'clock news came on for the line to be moved on, now it's over within hours," says one slightly exhausted press officer), but its ability to win over voters in crucial seats is perceived as relatively limited. (Twitter has issued its own research claiming the opposite.) One criticism raised by some was that Twitter's location-based ad targeting was not precise enough to ensure targeted ads were always reaching voters in the correct constituencies.

Still, there were three strong points in Twitter's favour cited by campaigners: First, party activists, who vote for a party regardless, can be fired up on Twitter and encouraged to spread a core message. Second, hashtag movements and ideas that begin on Twitter (such as the #Milifandom and mocking of the #EdStone) can sometimes get a mass audience and focus the press. Third, it can develop its own online ecosystem, as in Scotland, where the first minister has a habit of personally talking to journalists about their toilet habits.

Facebook was perceived as one of the best ways to reach swing voters who rarely engage with politics.

Paid-for YouTube attack ads have become a thing.

Instagram has not had the biggest impact.

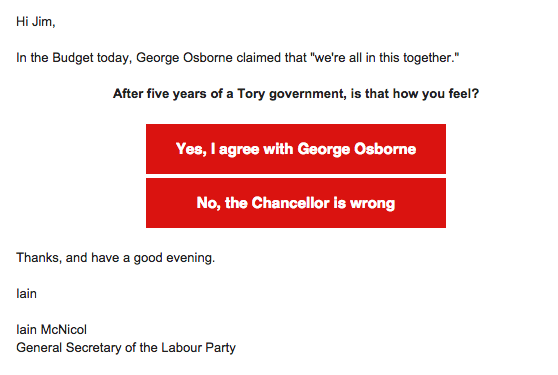

But the parties agreed that the real online campaign tool that mattered was a deeply unfashionable one: email.

And that's how the parties viewed their social media campaigns.

What worked in reality will become clear over the coming weeks.