A lot has been written about how the UK's political parties will be campaigning online during the election.

Scottish Labour is on Snapchat. The Conservatives are spending money on YouTube ads. On the other side of the world, government ministers are doing interviews in emojis. In short, politics has run face first into the internet – and the internet has got politics in a headlock and given it a kicking.

But this is just the latest stage in a long campaign by political parties to get in touch with voters over the internet. It's now almost two decades since the UK's major outfits made their first tentative steps online, and these initial websites can be still be found using the Internet Archive machine.

Understandably the early online efforts of political parties now seem a bit basic, given the potential audience at that point mainly consisted of about two dozen people equipped with boxy machines running Windows 3.1 and an AOL dial-up account.

But mainly they just seem wonderfully utopian and pioneering.

Labour was one of the first parties to get online. This is what its website looked like in 1996.

The website allowed you to read Labour's policies!

There's not much here that couldn't appear in a manifesto today:

People are fed up with old-style politics and politicians. They feel they have no control over their lives or the laws passed that affect them. Everyone knows that the political system is not working properly. They want a change. New Labour wants a more open politics, with decisions being taken as near as possible to the people they affect.

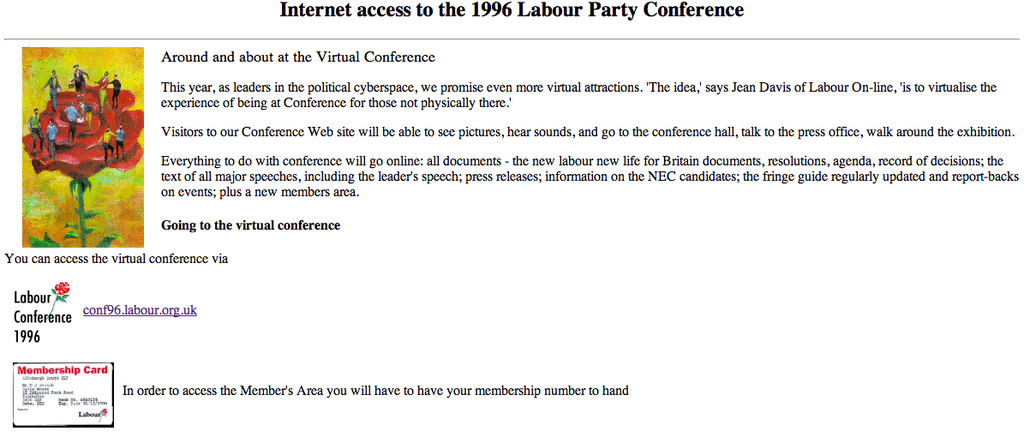

Back in 1996, the Labour party website promised "the experience of being at Conference for those not physically there".

It said:

This year, as leaders in the political cyberspace, we promise even more virtual attractions. 'The idea,' says Jean Davis of Labour On-line, 'is to virtualise the experience of being at Conference for those not physically there.'

Visitors to our Conference Web site will be able to see pictures, hear sounds, and go to the conference hall, talk to the press office, walk around the exhibition.

It is unclear whether this authentic conference experience included pictures of drunk journalists, bored party members, and despairing press officers.

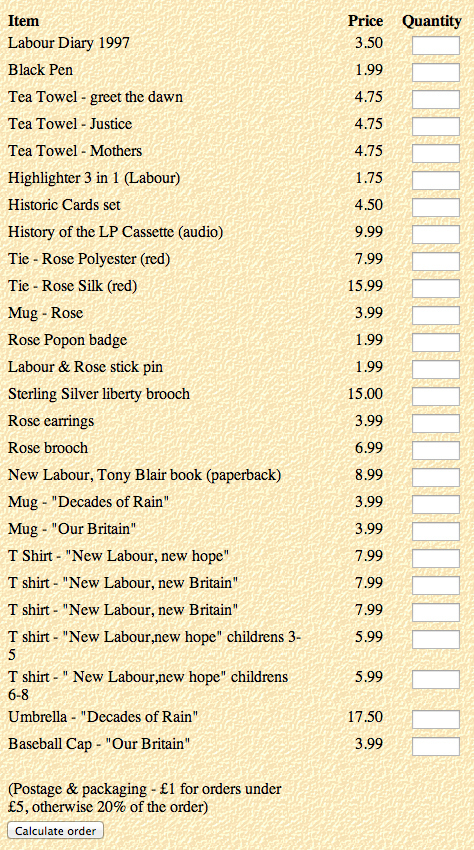

Those who couldn't make it to the event could purchase goods from an online shop.

It wasn't just Labour. The Liberal Democrats were online at the same time.

They actively encouraged users to email their thoughts directly to the team drawing up their policies.

The website also provided pictures of a fresh-faced Charlie Kennedy.

And linked to the Labour and Conservative sites in the name of internet friendliness.

In short, the Lib Dems were the "party of the nineties".

But the Conservatives' website from 1996 is the real deal:

And a brilliant post in the name of John Major claiming the internet as a victory for the Conservatives:

Welcome to the Conservative Party's Home Page on the World Wide Web. The information here will be constantly updated.

Every breakthrough in communications technology this century has started under Conservative Governments: the BBC, ITV, Channel 4, local radio, mobile phones, satellite television.

So it is not surprising that Britain already has more people connected to the Internet than any other country in Europe.

It was not the State that created the Internet. It was millions of individuals, just like you.

I hope you enjoy surfing our pages.

John Major

There's a press office section with a terrifying bit of stock photography.

And there's a section of the website entitled "A Lighter Note" that promises a fun take on politics.