Confronted by moral and ethical dilemmas that we grapple with on a daily basis, our habit as modern Indians is to look outside our culture to find solutions. We look particularly to the West.

But what if I were to tell you that you do not have to look too far to learn about harmonious modern ways of living? What if I were to tell you that your highly-liberal role models, who thought way ahead of their times, reside much closer home?

Yes, modern role models and the liberal ways of life are buried in our own past. Ancient Indian mythology and theology promotes concepts that are in tune with many needs of modern society. Let’s dive into some examples and look at how we can take a cue and learn from our own traditions to lay the building blocks of a futuristic social set-up.

1. Freedom of expression

There is no translation for the English word “blasphemy” in Vedic Sanskrit, the language of ancient India. This signifies that speaking your mind about Gods, sacred notions, and religious practices wasn’t curbed.

The same is depicted by an incident in the Natya Shastra, the more than two-thousand-year-old text describing performing arts in ancient India. In this text, an account is given of the first play that was ever performed, which was apparently insulting to some of the divine beings in the audience. They were agitated and wanted the performance stopped.

They were prevented from doing so by Lord Brahma. He conveyed to them that what takes place within the boundaries of the stage is sacred and the performers have the liberty to say what they want. Freedom of expression at its finest.

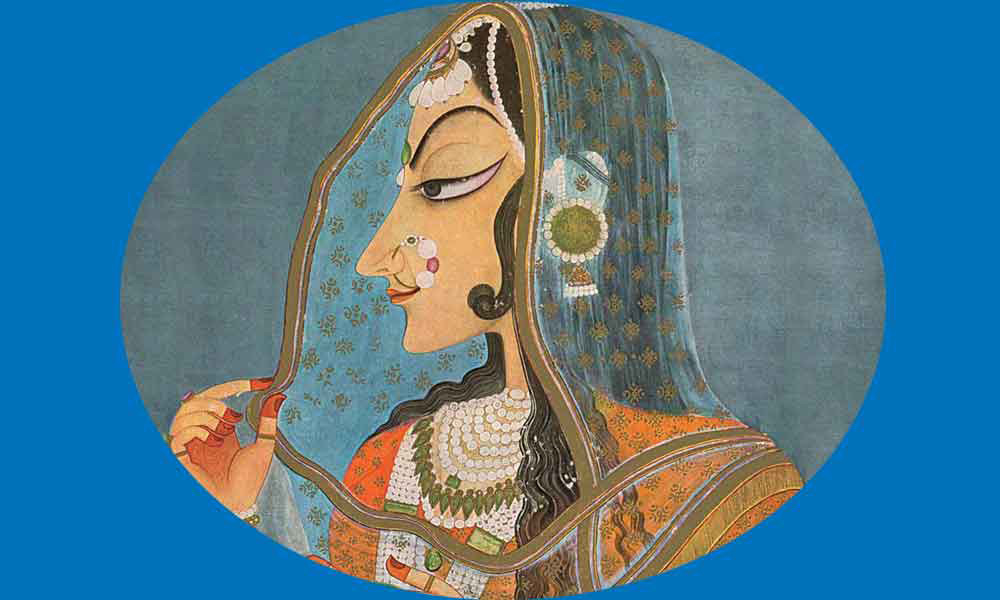

2. Women's rights

One of our ancient scriptures clearly states that the Gods abandon any land where women aren’t respected. The Rig Veda highlights the presence of Rishikas – woman Rishis – in Vedic times. For context: during the Vedic period, Rishis were revered and held the highest status in society. They were, in some ways, akin to the prophets and messiahs of the Abrahamic faiths. This directly indicates what an evolved society it must have been. Women were respected and held the highest positions of reverence.

Furthermore, the names of some of the Rishikas, as mentioned in our ancient scriptures, when loosely translated mean “independent,” “auspicious,” “limitless,” “courageous,” and “scholarly”, signifying that they thrived in an equal social set-up.

This culture needs to be revived in modern India. "Equal" is the key term here; not pro-man or pro-woman but equal. Equality forms the very crux of positive feminism. In a society where both men and women are treated as equals, everyone peacefully move towards prosperity.

3. Casteism

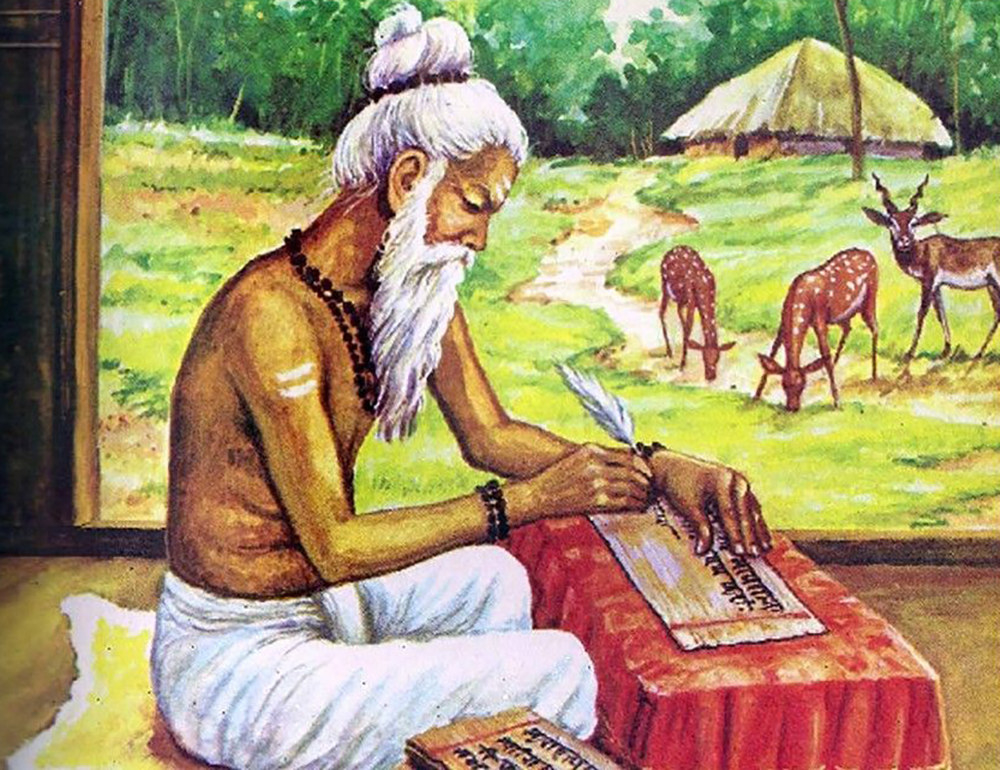

In ancient India, hierarchies were not based on birth, but on karma, which ensured that individuals progressed based on merit. For example, Maharishi Valmiki wasn’t born a Brahmin but he still went on to attain one of the most revered positions in society, that of a Rishi. Similarly, Maharishi Satyakam Jabali was the son of a single Shudra woman. But his intellectual brilliance ensured that he attained one of the highest honours in Lord Ram’s kingdom and became a Rishi.

Technological developments in the field of genetic research today have made it possible to prove that there was no birth-based caste system in ancient India. Modern genetic research has shown that inter-mingling (i.e. children born from inter-marriage) between different genetic groups was quite common in ancient India. And this intermingling between different genetic groups stopped somewhere around 1500 to 2000 years ago.

Intriguingly, this also corresponds to the period that Dr. Ambedkar had postulated the caste system became rigid and birth-based. So, it seems quite clear that ancient India was not casteist. The system we have today, where hierarchy is decided by birth, is a corruption of our progressive ancient ways.

4. LGBT rights

Various Hindu texts and scriptures feature queer folk and also showcase the relative acceptance of sexual differences in people to an extent that it was a non-issue.

For example, King Bhangaswan, changed his gender and turned into a woman without his choice being curtailed, and went on to give birth to many children. Similarly, the founder of the Chandravanshi clan, Ilaa, born a girl, later changed into a man called Ila. In fact, one of the names of ancient India was Illaavarta, in honour of Ilaa.

Even the Smritis – various different law books penned down at different stages in time – have been fairly liberal towards homosexuality.

All the above instances show that many answers to the future lie in our past, in our ancient scriptures. Indian myths and ancient texts actually aid the cause of liberalism.

By being liberal and open-minded, we are not being less Indian; we are in fact being more Indian. We are honouring our great ancestors.

Amish Tripathi has authored five books — The Immortals of Meluha, The Secret of the Nagas, The Oath of the Vayuputras, Scion of Ikshvaku, and Sita – Warrior of Mithila. His books have been translated into 19 Indian and International languages.