Peter Tatchell has attacked Ed Miliband’s pledge to posthumously pardon gay and bisexual men convicted under the old gross indecency laws as “wrong and offensive”.

The leading LGBT rights activist argued that it fails to offer clemency to those who fell foul of many other homophobic laws.

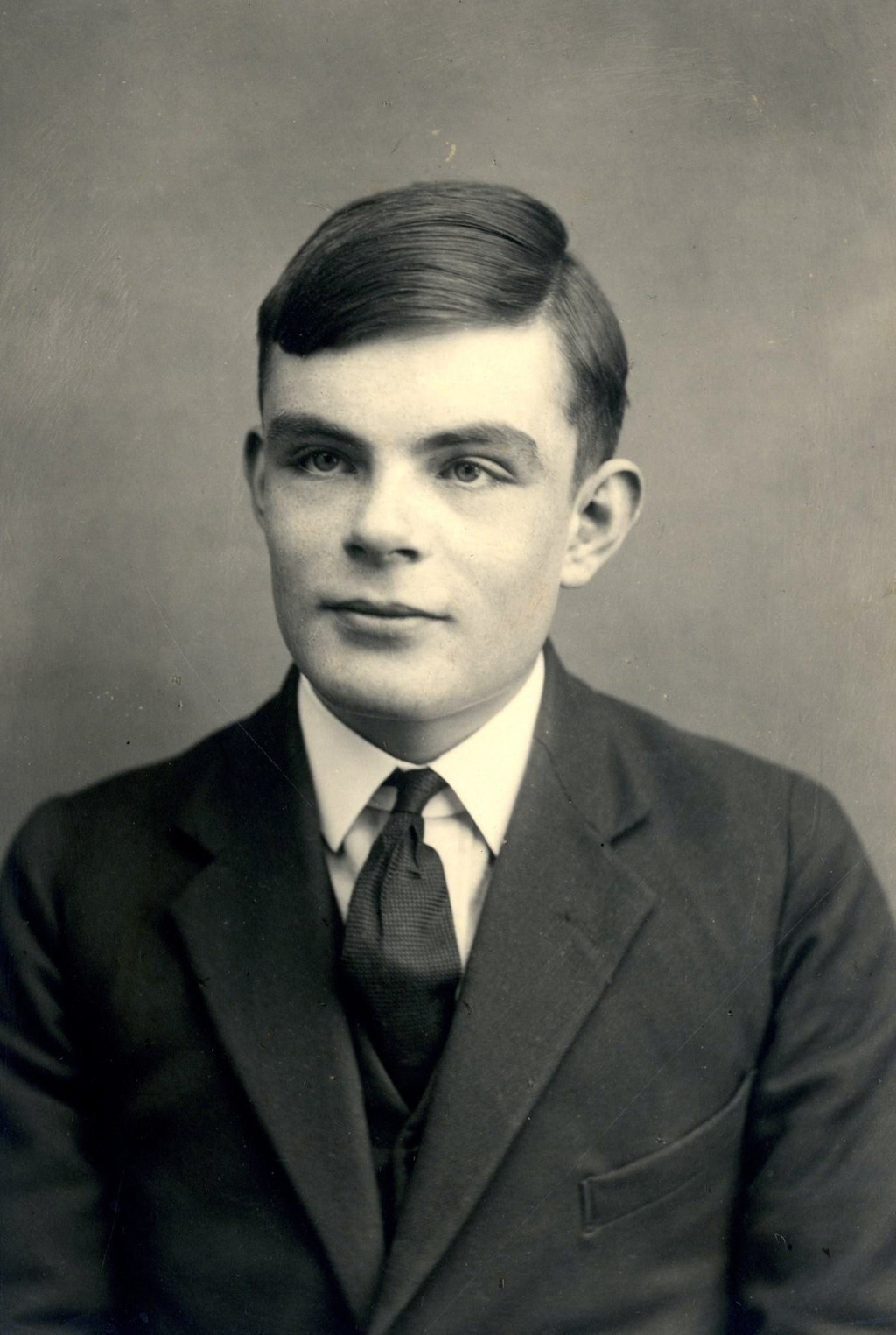

It followed this morning's announcement that under a Labour government, a "Turing's Law" – in memory of Second World War codebreaker Alan Turing – would allow the friends and relatives of those found guilty in the past to apply for a royal pardon.

“I’m sure Ed Miliband is well intended," he told BuzzFeed News, "but restricting the pardon to only the offence of gross indecency is very wrong and offensive."

He added: "The pardon should be extended to all men convicted under all homophobic laws where their behaviour is no longer a crime."

Miliband's announcement followed an almost identical promise last weekend by Simon Hughes, the Liberal Democrat justice minister.

"Both [pledges] are fundamentally flawed," said Tatchell. "There can't be a general pardon because some men may have been convicted under anti-gay laws where their actions involved underage, or non-consenting sex, or a sexual act in a public place witnessed by a member of the public who was offended."

The Guardian reported last week that it is fear of such complications that has so far prevented the quashing of all convictions, amid fears in Whitehall that a blanket pardon could inadvertently apply to paedophiles.

Tatchell, a veteran human rights campaigner of over 40 years, also believes those convicted under homophobic laws deserve more than a pardon.

"I'm pressing the government for an apology to all men convicted of consenting adult same-sex behaviour that is no longer a crime today," he said. "That's easy to do.

"And an apology is much better than a pardon because it recognises that a wrong was done and expresses sorrow for that wrong. A pardon does not dispute that a person does wrong – it is merely an act of mercy and clemency by the state."

The gross indecency law under which Alan Turing was convicted – after which he chose chemical castration rather than imprisonment – was only repealed in the 2003 Sexual Offences Act.

But several other laws enabled police to arrest and convict men for same-sex behaviour, some of which involved no sexual contact.

"Procuring and importuning merely involved abetting, facilitating, encouraging, or inviting a sexual act, and they were all only repealed in 2003," added Tatchell. "And Section 5 of the Public Order Act 1986 was used to arrest same-sex couples for merely kissing and cuddling which was deemed to cause the public 'harassment, alarm or distress'.

"There are also ancient laws like the Town and Police Clauses Act of 1847, which includes indecency, that was used against gay men. Likewise the Ecclesiastical Court Jurisdiction Act of 1860, and all behaviour likely to cause a breach of the peace. If a same-sex couple kissed, the police, in some instances, deemed such behaviour as likely to cause a breach of the peace and they were arrested and prosecuted."

Discussion of such issues has mounted since Gordon Brown apologised in 2009 for Turing's conviction, which eventually led to a royal pardon being issued in 2013.

"What was right for Alan Turing's family should be right for other families as well," said Miliband in a statement.

He added: "The next Labour government will extend the right individuals already have to overturn convictions that society now see as grossly unfair to the relatives of those convicted who have passed away."

But Tatchell remains concerned that police behaviour towards gay and bisexual people remains troubling.

"In 2013 we had the DNA witch hunt," he said. "The police were instructed by the home secretary to conduct and compile a DNA database of serious sex offenders. Some police forces decided this should include gay men convicted of consenting adult same-sex behaviour. The police turned up unannounced at people's houses to demand they give DNA samples and threatened those who declined with arrest. It was only stopped after I intervened and pressured the Association of Chief Police Officers."