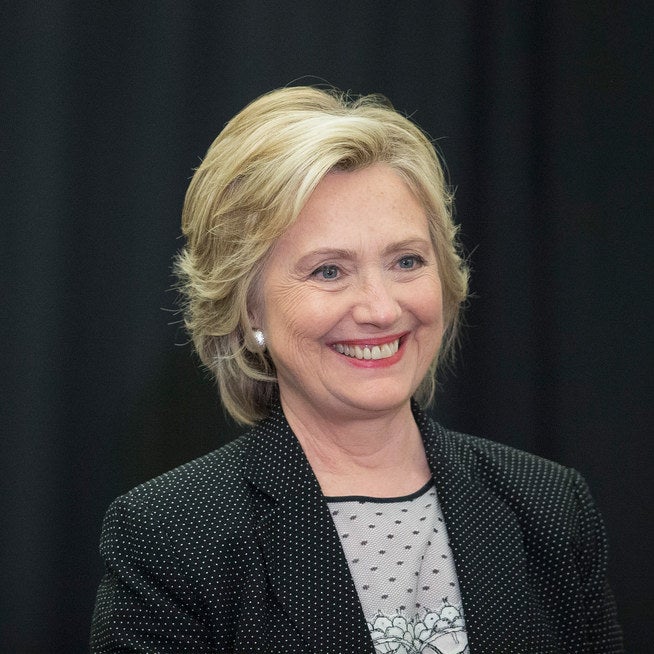

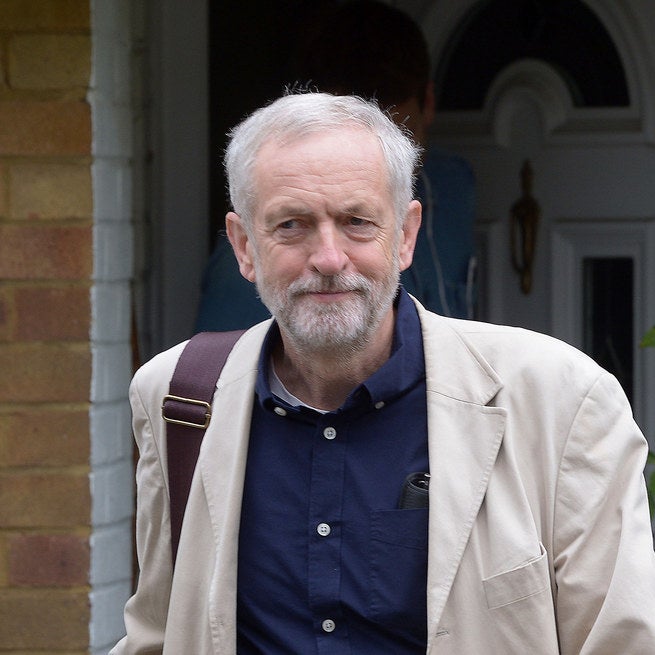

She is a US presidential candidate, a former secretary of state and first lady, and a woman who mixes with – and emails – the global elite. He is a veteran left-wing Labour MP who likes to cycle to work, has never held a frontbench position, and has spent the last 30 years backing unfashionable causes while being barely known within his own party. In any normal circumstances Hillary Clinton should have no reason to worry about Jeremy Corbyn.

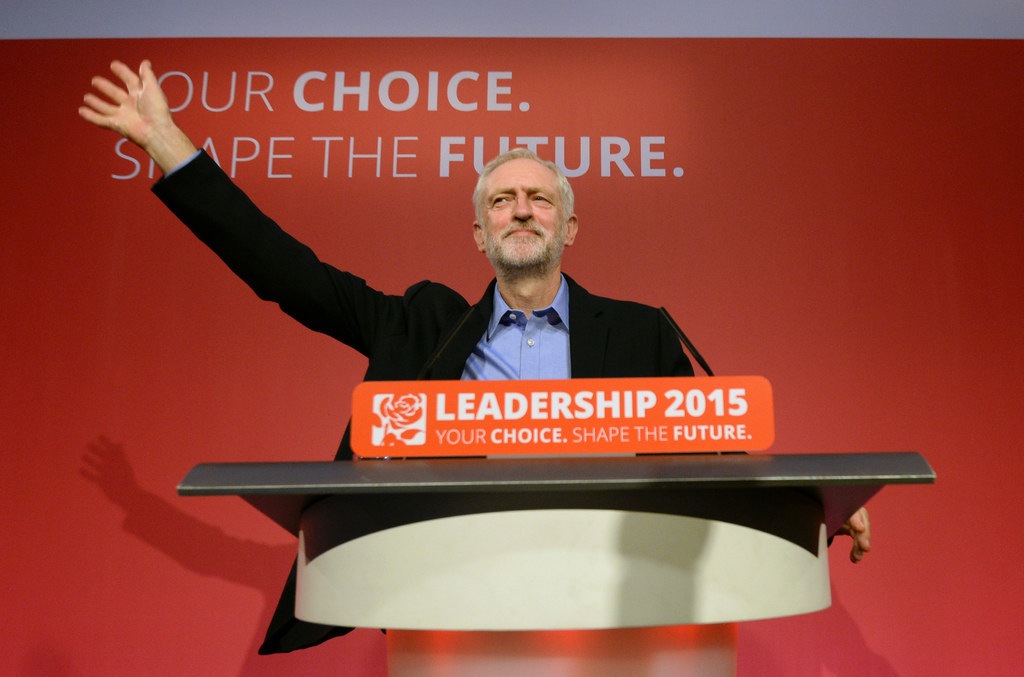

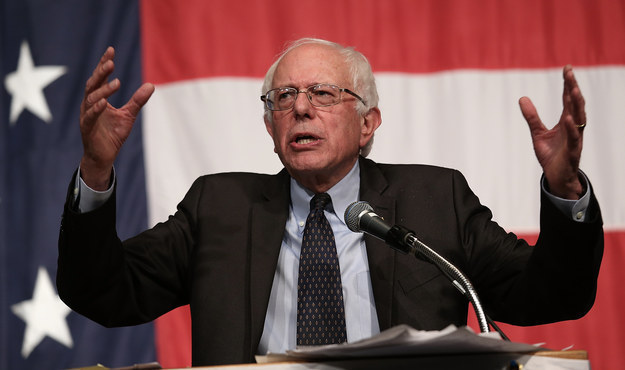

But on Saturday Corbyn, who started the race as a 100/1 outsider, a charity case who made it on to the ballot through the kindness of fellow MPs, was elected leader of the British Labour party and Her Majesty's Official Opposition with almost 60% of the vote. And the movement that took him there should keep Hillary Clinton – currently facing her own left-wing challenger in the form of Bernie Sanders – awake at night.

Establishment candidates elsewhere in the world, such as Clinton, have cause to be worried by the forces that swept Corbyn to victory: a dedicated left-wing activist base who care more about purity of values than winning general elections, a devotion to an individual leader, and exasperation with soundbite politics. It seems that the normal rules of political engagement are on the shift, at least within activist groups who can control candidate selections.

Because the strangest thing about Jeremy Corbyn's elevation to the top job is that just a few months ago no one, including Jeremy Corbyn, thought it was remotely possible. This is a 66-year-old man who has been in parliament since 1983 but has never held any major role, rebelling against his own party so often that Labour whips stopped even bothering to talk to him. Instead he pursued a lonely furrow campaigning on unfashionable human rights causes and presenting a show on the Kremlin-backed Russia Today.

Instead he won by a landslide. There's a big caveat when comparing the circumstances to US politics, since British party leaders are decided by a few hundred thousand paid-up party activists who tend to hold strong political beliefs rather than through a primary system. But here's what Clinton's team should learn from the success of the Corbyn campaign:

1. Corbyn wasn't taken seriously until it was too late.

He was seen as such a weak outsider – the archetypal token candidate destined to finish last – that some Labour opponents even lent him nominations to get him on the ballot in a friendly gesture. Some of these people have since admitted they were "morons" for failing to realise how this patronising gesture would affect the party. The Labour establishment was completely shocked and didn't know how to react when they realised that the party's supporters actually liked Corbyn.

It's easy to dismiss Sanders' poll lead in Iowa as a blip – but that's exactly what pundits and Labour insiders did with Corbyn in the UK. The big mistake Corbyn's opponents made was to ignore him until late in the race, rather than confront his policies and issues about his electability early on.

2. Corbyn engaged with young party activists on an enormous scale.

This led to a mass surge of new supporters and activists into the party. It's telling that a generation of young left-wingers who came of age during the era of anti-austerity and Occupy protests found an outlet in the form of a white-haired, old-school socialist. Warnings from the party establishment that his policies were unworkable and a throwback to Labour's wilderness years in the 1980s were dismissed as ancient history – for a start, many of the young Corbyn supporters weren't even born in that decade.

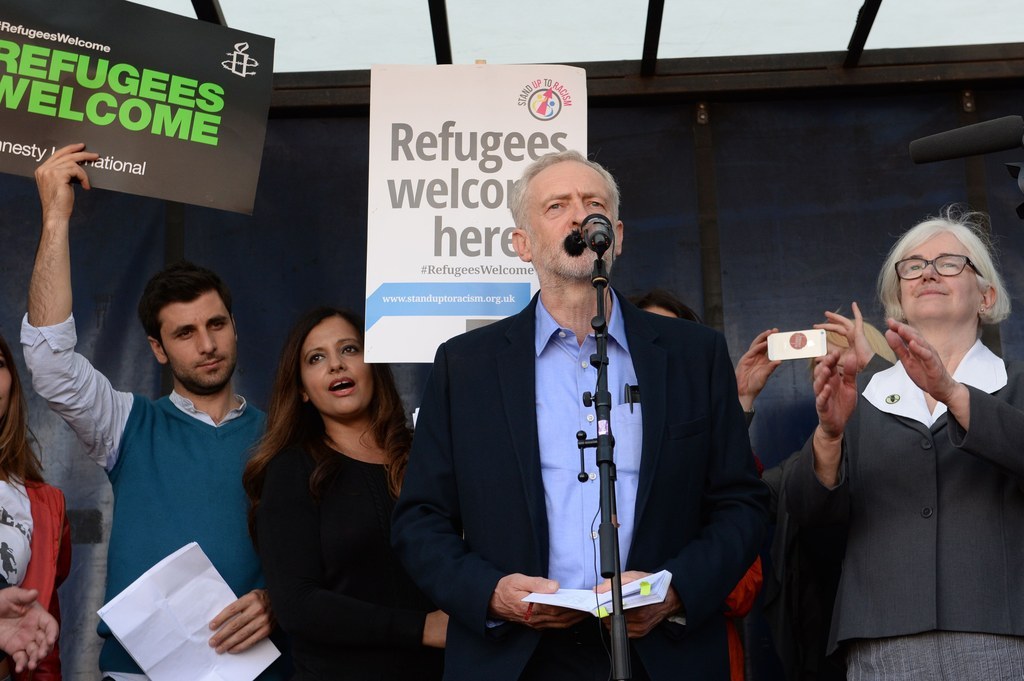

The lesson of the Corbyn campaign is that you ignore the mass mobilisation of a party's young activists behind a candidate at your peril. "Who says young people aren't interested in politics? Politics wasn't interested in young people," a delighted 66-year-old Corbyn told supporters at his victory rally, where some Corbyn activists could be overheard talking about flying out to the US to help out Sanders.

3. Corbyn's ad hoc campaign massively outperformed his opponents' top-down media bombardment.

The establishment candidates fought more traditional campaigns that relied heavily on set-piece speeches and carefully controlled announcements. Corbyn took to the streets and let his supporters do the work on his campaign's behalf. Volunteers flooded into phone banks and venues were booked and paid for by local groups, with the left-wing MP forced to address crowds on the street who had been turned away.

4. Voters raised on social media reject soundbite culture.

One poll found 57% of Corbyn supporters use social media as their main source of news, far above the national average. Corbyn's team have increasingly rejected traditional outlets, refusing to speak to The Sun – the UK's biggest-selling newspaper.

Traditional political attacks don't work among this support base: Attempts by opponents to portray the MP as an extremist with a tendency to share platforms with unpalatable speakers fell flat – or even backfired spectacularly in the case of Tony Blair's repeated interventions. Even a newspaper headline that accused Corbyn, somewhat out of context, of saying he thought Osama Bin Laden's death was a "tragedy" didn't stick. Instead, it just hardened his supporters' resolve to face down what they perceive to be the unfair attacks of a worried elite. What actually went viral were lengthy Corbyn speeches or large paragraphs of texts setting out his political worldview.

5. Labour activists' desire for authenticity allowed Corbyn to claim to represent the true soul of the movement.

This is the biggest danger for Clinton's team. Political activists find it irresistible to be able to say that you represent the real deal, and it's easier to post a Facebook status saying you believe in a politician who represents the full-fat version of an ideology rather than a watered-down, compromised equivalent designed to appeal to the centre ground. It seems that the nature of left-wing politics – the former Labour prime minister who led the party to three general election victories – was a major motivating factor for getting the Corbynites to turn out.

Both Corbyn and Sanders can point to a voting record that has barely changed over three decades in government, unsullied by the legacy of messy compromise and contradictory quotes that comes with governing. Corbyn has always been anti-war, anti-university fees, and a lifelong environmentalist: He even once signed a parliamentary motion declaring humans are "the most obscene, perverted, cruel, uncivilised and lethal species ever to inhabit the planet". His backers aren't going to be swung by claims his policies will lead Labour to electoral doom – instead they feel they've finally found a decent man in politics who actually believes in something.

Sanders has sent his congratulations to Corbyn on his victory, while the Labour leader, for his part, recently told BBC's Newsnight programme that he's been "exchanging leaflets and badges" with the US senator for Vermont.

There are still massive differences – especially with regards to money – between the US and UK political systems, while the US tradition of open primaries gives less power to the hardcore party activists when it comes to selecting candidates. But if Sanders has any sense he'll be sending his campaign team on the next flight to London to find out what just happened. It's quite a year for white-haired old socialists.