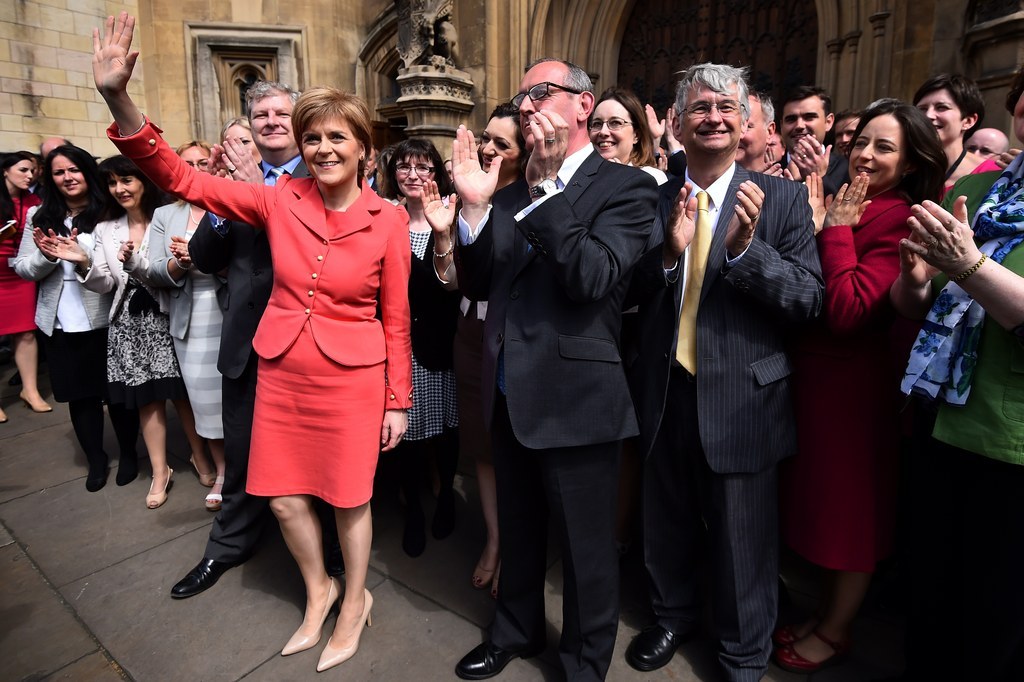

It's been one year since voters in Scotland went to the polls and decided against their country becoming independent from the rest of the United Kingdom. Since then, the Scottish National party has won an astonishing victory in the general election and has ended up with 56 MPs in the Westminster parliament they wish to detach from. Polls show support for independence is slowly rising, and Nicola Sturgeon, who took over as SNP leader following the resignation of Alex Salmond, has said there could be a repeat referendum in the next Scottish parliament.

To mark the anniversary of the historic vote, BuzzFeed News spoke to six of the people who shaped both sides of the referendum campaign. Individually, they told the story of why Scotland voted against independence, what happened behind the scenes in both camps as results came in, and why the future of the UK has irreversibly changed because of what happened in Scotland last September.

The participants:

Alex Salmond: The first minister during the independence referendum and leader of the pro-independence campaign, who has since stepped down as leader of the SNP and been elected MP for Gordon.

Alistair Darling: The former UK chancellor and leader of the Better Together campaign.

Blair Jenkins: The chief executive of Yes Scotland.

Ruth Davidson: The leader of the Scottish Conservatives.

Mhairi Black: Emerged as a leading campaigner for Yes during the referendum campaign, and has since become an MP and the rising star of the SNP.

Johann Lamont: Leader of Scottish Labour during the campaign. Subsequently resigned as leader because of UK Labour's handling of the referendum.

On the morning of 18 September last year, were you confident of victory?

Salmond: I was confident. I spent the day campaigning in Aberdeenshire and it was all fine, all going well, but I remember there was just one girl: She was scared out her wits, she'd never voted before, and she was worried about what the right thing to do would be. She had a nice tidy house, next to nothing in it, she had a baby, her, and a dog. That's all she had, and she was scared.

I was in there for about 20 [minutes] and eventually I gave her a hug and she promised to go out and vote. When I came out they [Salmond's campaign team] couldn't believe I'd been in there for 20 minutes and they asked what was wrong and I said it was fine, but it wasn't fine really. You can't hug everyone in the country. That was the only suggestion that gave me a tremor that all wasn't well.

Darling: I was surprisingly confident we would win. On polling day there is nothing you can do to change things, you just have to wait for the result. But, as I went across to Glasgow to hear the results coming in, I was confident we had done enough.

Black: I didn't feel confident, naw. In the team they always slagged me because I was Miss Sceptical, I was always playing it down. I knew whatever way it went it would be relatively close but by that point I'd seen so much momentum and the feeling and I was watching all these vocal people and, you know, I thought we might just do it. I just started to believe it.

Lamont: The nearer it got to the time, the more worried I was. On the day, I was very, very anxious. All the figures were telling me that Glasgow was going to be fine, Dundee too. But I just had a sense of unease towards the end because the Yes people had killed the rational argument – the argument about implications. They created the impression you could still share and pool resources after independence. They'd neutralised any of the positive things people felt about being part of the United Kingdom.

Jenkins: We thought we were winning it by something like 10 points – the reverse of what the result would be. We thought there was a margin for error there. The poll, the Murdoch poll that put us ahead about 10 days before the vote, that didn't surprise us because that's what our polling was telling us. The other side did a poll which showed us ahead as well. All these things made us think we were going to do it.

Davidson: It's really strange. I never believed we were going to lose, but that doesn't mean I wasn't nervous about it. I was scared we would lose but I never believed that we would. But by that point we were doing 80,000 voter contacts a week so [Better Together's] numbers were far more accurate than anything a pollster could do. We had it at 10 or 12 points and that's what it proved to be. We had to trust those numbers.

At what point did you first realise what the result was going to be?

Salmond: I was doing work on both a concession speech and a victory speech. More on the victory speech, I thought that was more important to get right. Then at about 1:30, Clackmannan came in. I was watching the TV and [Salmond's wife] Moira turned to me and said, "Is that really bad?" and I said to her, "Ach, it's just the first result." But I knew the game was up. Clackmannan is Scotland – rural Scotland, urban Scotland, small-town Scotland, industrial Scotland. That was it. I went upstairs and I did the concession speech. I've had better moments.

Darling: The nationalists had to win places like Clackmannan where there's been a history of people voting SNP in the past. It gave us a great indication of how people had voted. In all these things you look for indicators, but having said that I just felt throughout the campaign that there was never a point that I thought we would lose.

Black: I don't remember the constituency but I remember looking at the telly and getting that gut feeling that we're no doing this. It was horrible. Once our count was finished I walked out to the car, trying to count up all the numbers, clutching at straws, and realised there was no chance in hell we were going to win this. Then I went to a church hall where there was a big projector, I was in for about 10 minutes, and I think it was [then Labour MP] Iain Davidson I saw speaking, and I thought, "Naw I just cannae whack this any more." I went home.

Davidson: I was on air at 10 for the BBC with Huw Edwards, and eventually the first result came in, which was Clackmannanshire. As soon as that came in I knew we were fine. It was a relief more than anything else, a release of tension. I was on air with [SNP MSP] Humza Yousaf, he was sitting next to me and he just kind of crumpled a little bit. He was deflated after that and I thought, yeah, they needed that.

Jenkins: The first result, Clackmannanshire. We still hoped there would be surprises elsewhere, but that was the first time I seriously began to think we were not going to win. It dampened the mood very considerably. It became clear [in Yes Scotland HQ in Edinburgh] what was happening and people had invested so much emotion and energy and shoe leather into the effort. People were hugely disappointed, shocked, gutted.

Lamont: I remember, most clearly, doing an interview with Jim Naughtie after the results, about 7am, and that's when it sunk in. He asked if I felt jubilant. I said, "No, I don't. I know lots of people who cared passionately on the other side will be disappointed." In myself, I felt quite troubled. I didn't feel any of the elation at all – I went back to the celebrations and I didn't feel any of that at all.

Once you knew the fate of the referendum, what did you do?

Salmond: It was time to go to the airport. There's that famous picture of me when I was looking at the results on my iPad, it's an iconic picture now, but it was just me checking the results. If the photographer had asked for a photo I would have given him one. We boarded the plane, Moira and I and some private office staff. We flew from Aberdeen to Turnhouse and by that time that picture was all over social media so I said to Moira, "Right, when we get out of here, look cheerful." There's a photo of us looking quite jolly in the back of the car but of course no one published that one.

Darling: You always feel a sense of relief once things like this come to an end, but things move on very quickly. I knew I would have to give a speech for the 7am bulletins so that's what I was concentrating on. The next bit of the journey started as soon as the last one finished. There were umpteen interviews – I don't think I got my breakfast until 10am. There were celebrations among the team, and winning obviously does an awful lot more for you than the opposite, but I'm not the most demonstrative person.

Black: I remember walking in to the house, my mum had stayed up, and she gave me a hug, and that was it. The tears started coming, I was welling up. It honestly felt like mourning; this was two years of your life. I know it meant so much to vulnerable people, all these doors that I'd chapped, people who were totally disenfranchised from politics had suddenly come to life. They suddenly put faith in politicians and politics only to have it snatched away from them. It broke my heart. I was incredibly down.

Davidson: I'd expected to be punching the air and running around with a T-shirt over my head like a Premiership footballer who'd scored a goal. It didn't feel like that at all to me. It was just relief, utter, utter relief that I hadn't lost my country. That's what it felt like. There had been free drink put on and people were quite drunk, which was fine and I'm glad people were happy because people had put a lot of work in and stuff, but I'm not sure it looked very professional. I stayed off the floor for much of that and stayed upstairs in the boardrooms to have a bit of peace and space in my head.

Jenkins: What was interesting was how quickly the mood changed. By the time you started getting the results through from Glasgow, Dundee, around 4 or 5am, there was a lot of pride. I think the turnaround started there in [Yes Scotland HQ] Dynamic Earth. People were saying the losers were acting like the winners, that started in that building. The determination to go on started there as people talked about it.

Lamont: I wasn't quite going about being glum and miserable and saying we're all doomed. Although I couldn't have a glass of wine because I was going to be doing telly, maybe that makes me naturally grumpy. It felt like an election victory in [Better Together HQ] and of course there was joy in the moment, but I was wondering what it would mean. What would happen next.

Did David Cameron misjudge his speech that morning when he brought up the issue of English devolution?

Salmond: At that moment I just thought, "You stupid, stupid man." If I was delivering a victory speech I would have spent a lot of time talking to No voters. That's what's right, bind up the wounds of the nations and get on with it, make the effort. But this silly, silly man struts out of Downing Street and tries to put Scotland back in its box because Nigel Farage was waiting on his shoulder. I knew immediately he had opened a political door. That was the moment I decided to resign. I'd thought about it and I'd told Nicola I would think about it during the campaign, but at that moment I knew what I had to do. I went back to Bute House and composed the resignation speech.

Cameron isn't a big enough politician to realise what you do when you win. He's not able to rise to that occasion. So he left the door open, and if you're going to take advantage of that opportunity then you have to clear the decks. At that moment I knew the SNP would win the election, but you couldn't fight that with people pointing to me and saying, "Why are you still here?"

If Cameron had made a different speech, would you still be first minister now?

If Cameron had made a different speech then there might have been an argument to make sure his declaration was redeemed, and we'd see what's what after then.

Darling: I spoke to [Cameron] at about 6 that morning and I told him it would be a massive political miscalculation to open up a new front which would let Alex Salmond back in the front door again. I said there's an issue to be discussed but it shouldn't be done this morning, you have problems in the Conservative party which you have to sort but don't deal with them today. He'd clearly already taken the decision though, and he wouldn't go back on it.

Davidson: My feeling is that he was happier than me. I spoke to him on the phone that morning and it had maybe sunk in with him in a way it hadn't with me. I really was in quite a space where I wanted to be quiet and away from people. I didn't want to be having a party. But the mood from down there was very upbeat, he was very relieved and happy. A lot of people can argue over [the speech]. I think there was a real incumbency on the prime minister of the UK to make sure the rest of the UK felt it was getting a fair deal as well as Scotland.

Lamont: I still don't know why Cameron did what he did on the 19th. On the Yes side, they were waiting for an opportunity. It had to be Scotland being robbed at the last minute by a dodgy penalty, it couldn't be that people just disagreed with them. Cameron opened that up and we're still dealing with that now.

Why did the SNP do so well in the election despite losing the referendum?

Salmond: The Scottish phenomenon is distinct and separate, but it's also part of a more broad phenomenon: the distrust of metropolitan politicians, the establishment forces, in fact a contempt. It's a general feeling, and that is heightened by politicians seeming incapable of understanding the questions being put to them. Those two things, put together, are very, very powerful – if you overlay the general contempt for metropolitan politics with the national dimension of Scotland, you have a force which is irresistible.

Darling: If you look at what's going on in politics, not just in Scotland or the UK but right across Europe, I think seven years after the banking collapse – it is seven years ago this week that Lehmans went down – we're still in the political backwash of that. There's a lot of people who understandably think we're seven years on, things don't seem to be getting better, they're disillusioned about the established political order, they want change, they want something better. They may not all want the same thing but they want something better. The nationalists, to give them credit, harvested that vote well between the referendum and the election.

Jenkins: Immediately after Alex's resignation, the SNP focus went on to the transition, there was no dwelling. Alex shifted the story away from "Why did Salmond lose?" to "What kind of leader will Nicola be?", and then there was this huge rise in the SNP and Green membership. It was clear very quickly that all the energy remained on the Yes side. It was beginning to dawn on people that the Yes movement, despite losing the referendum, it came out stronger than it went into the referendum.

Davidson: Looking back, I think there was more that could have been done directly after the vote in September. The reason we didn't stamp authority on the win is because we wanted to give people space, we didn't want to be triumphalist. It was done with the best of intentions but I think that put us on the backfoot very quickly and we were always playing catch-up after that.

Black: On the 19th, as a family we went out for a drink. I just went, "Naw, this is different, I've not campaigned for two years of my life to give up now," and I started to realise everybody else was feeling like that. Beforehand I felt people had been cheated, lied to, misled. There was a lot of deliberate confusion and scaremongering. That anger turned into determination and I didn't want to let those people carry on getting cheated. Everything I was talking about at the doors, politics that matters, people genuinely being represented – I believe in it, so let's keep pushing for it. I didn't campaign for two years to go back in my box.

Lamont: I was fearful, but no one could have imagined the scale of the SNP victory. The other side of this is that we're now in a politics where it's perfectly legitimate for the government party, at every turn, to say everyone else is a liar. On the 19th, I made this point. We had to find what we had in common. We have a joint responsibility to bring each other back together, to accept the result, to build on it, and to act in good faith towards each other. Whatever's happened in the past year, that hasn't happened.

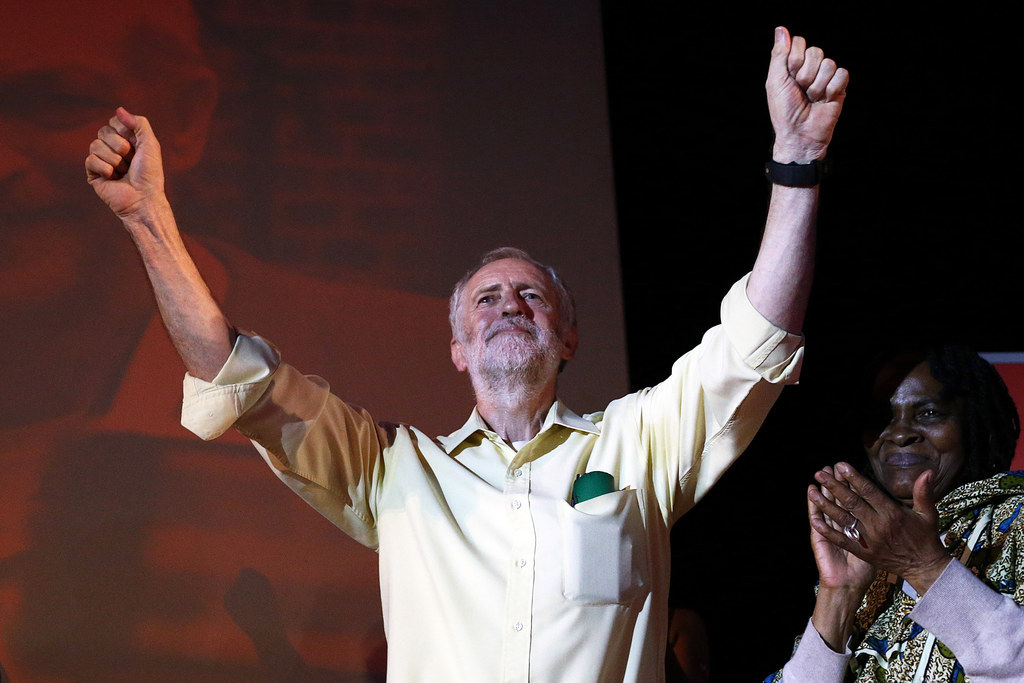

Can Jeremy Corbyn's Labour win support back from the SNP?

Salmond: Jeremy's problem, in my view, is not his policies, some of which I disagree with, and not singing "God Save the Queen" [on Tuesday] was just stupid. But his Achilles' heel is his unelectability. In history, Labour's weapon against the SNP has been "we can win": That doesn't look very convincing now. It's not his policies which will undo him, it's the Labour party. It's what's behind him, not in front of him. You can't fight front and back, believe me, and divided parties lose elections.

Darling: I firmly believe you need to occupy the centre ground, because politics is about winning a majority of people to support whatever argument you're putting forward. You can't do that from one side or another side without trying to get that middle part. It's not compromising, it's common sense, and the nationalists are a very middle-of-the-road political party in Scotland. You can never rule out things, but you do need to ask yourself, if he is going to win, he's got to make sure we have policies people support, that they feel comfortable with, and actually come to view that you'd do a better job.

Lamont: His biggest challenge is to try and understand, along with the rest of us, what's happened in Scotland and that his role in that has to be supporting [Scottish Labour leader Kezia Dugdale] and for that to be seen as a genuine partnership. It's not so much about who the person is, it's about their understanding of what has happened in Scotland and how to deal with a politics with such a close correlation with identity up with a general sense of being fairer than the Tories. They need to understand, for whatever reason, Scotland now looks at the political world as who will stand up best for Scotland. That's where we are.

Did the referendum change Scotland for the better or for the worse?

Salmond: I light up when I think about the referendum, but I think Scotland lit up as well. The process of the referendum is the most alive, exciting time I've ever had in politics. For people, as far as politics is concerned, it's the most exciting thing that's ever happened to them. Scotland is a changed nation, and a better nation, as a result of it.

Darling: The debate about independence is strongly held on both sides. It will always be there now. I don't think the majority in Scotland want to go into another two-and-half-year referendum campaign, frankly, and when we're talking about referendums we're not discussing policing, health, education, and a whole lot of other things which do actually affect people's prospects in Scotland.

Black: We've got to be one of the most politically educated nations in Europe, if not the world, now. It's incredible. Going into a pub or your staff room and hearing two plumbers arguing about a currency union, when would that ever happen otherwise? Secondly, there's a confidence about Scotland now. Scotland, from my perspective, has suffered. We've been in a sleepwalk for 30 years. We voted Labour to keep out the Tories and that was it, like we didn't deserve any better. We've realised we do deserve better than this.

Davidson: The referendum was incredibly divisive and we wanted to bring the country back together, but it's not in the SNP's interest for that to happen. It was clear in those first few weeks that they had no intention of that happening and I think that's very sad for the country. It is a tactical advantage to them to keep Scotland divided and I think that's a real, real shame. They're putting party interest before the country.

Jenkins: You can argue Scotland was the winner of the referendum. Young people are now so interested in politics, they want to be involved. That's an incredible legacy. People have sensed their power, and democracy in Scotland is now from the ground up and not from the top down. Nicola and the SNP are most in tune with that right now, but I'm sure the other parties are trying to tune into that feeling. No votes can be taken for granted any more.

Lamont: I think there's a bit of a rewriting about the referendum campaign – that all the belief and caring about Scotland was on one side. It's now spilling over to people believing the only people who care about anything in Scotland is the SNP. You can't live in a politics where you just deny anyone else is really worried about anything bar yourselves, it's just wrong.

Is another referendum inevitable?

Salmond: There are many factors pushing the timescale of a fresh ballot ever closer. I would say the failure to deliver the Vow is number one. Then Osborne's foot on the throat of the poor and vulnerable – austerity to the max instead of devo to the max – and him sauntering up to Scotland and saying we'll have 60 years of nuclear missiles without so much as a parliamentary vote. Cameron's German roulette with the Euro referendum, Scotland's European future, and the unelectability of the Labour party.

The first minister will lead the next campaign, and I won't be the chief executive of Yes Scotland, but I'll be a good supporting speaker.

Darling: Apart from death and taxes, nothing is inevitable. It think the answer to that question is, and this is a matter of cold political calculation on nationalists' part, there will not be another referendum unless they think they can win it. To lose one referendum is unfortunate; to lose two is a political disaster. If I was them I wouldn't count on seeing one any time soon.

If it happens, someone else would be leading it – I've moved on from that. It's something I strongly, strongly believe in and I would play my part, but I did that two-and-half-year campaign and the banking crisis. I think that's more than enough for one political life.

Black: I would take it tomorrow if I could, but it has to be the right time. It has to be when the people want it and sometimes people say that's a cheesy slogan, but it's a case of saying, "This is a democracy and if people want it then we have a duty to give it to them." So it's a case of judging when that is. But I have no doubt there will be another referendum at some point and I have no doubt that Scotland will be independent.

Davidson: I don't think it is. I think the SNP will do everything they can to push for one, and you've already seen a semi-acknowledgement that they'll only push for one when they think they can win it. Is that oil prices rising? Is that polling on 60% for a year? The big issue for the SNP is, look at Canada, if you lose one referendum you can go on to have another one. If you lose two, nationalism just falls off a cliff.

Jenkins: I think it's highly likely, but very few things in life are guaranteed. Things only happen because people make it happen. But it's highly likely, and highly likely that Yes would win. We'd be starting from a much stronger position. In terms of timing, my instinct would be to say 2021.

Lamont: You can never say there will never be another one, but there's nothing inevitable about anything. I don't like the idea of inevitability. That means somehow people's decisions are shaped by a force beyond themselves. I like being Scottish, cheering on the Scottish football team and supporting them at the Commonwealth Games, without thinking we must have an independent Scotland. I hope and I believe there is a future for people like me.