There is a definite change in the air at Labour HQ. Last month there was disbelief, anger, and even despair at the thought of Jeremy Corbyn becoming leader. Now, as the left-winger looks almost certain to claim victory, senior party figures are becoming more pragmatic. Plans are now being discussed at the highest level for life under Corbyn. The party is determined to make the best of it. But they don't really have a choice.

For a start, insiders are reassuring each other that Corbyn will not turn out to be as radical as he is made out to be. The MP for Islington North has some big ideas but he is an inclusive person, more than willing to listen to other opinions. "He has always been very cautious," one senior Labour aide insisted to BuzzFeed News.

Frontbenchers expect that Corbyn will form a "government in waiting" rather than a radical opposition. They are hopeful that every policy will be costed out and every plan will be properly thought through. That style of leadership might not please his legions of fans.

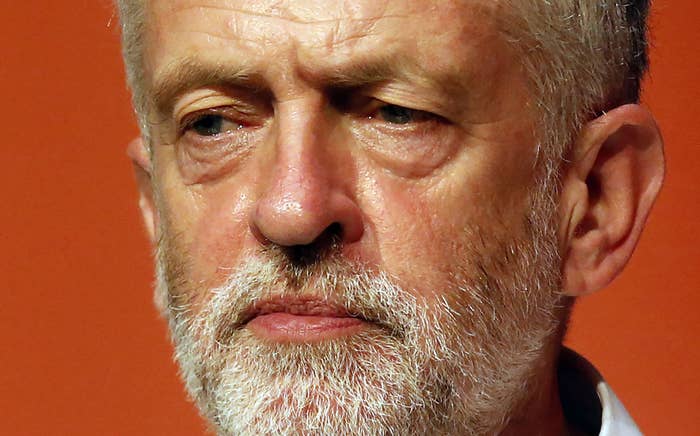

Corbyn has stormed ahead of his leadership rivals by being an "anti-politician", despite his 32 years in parliament. He's a straight-talker, a man seemingly unafraid to say the unsayable. But as the contest has dragged on this summer, it's clear that actually – whisper it – he quite likes to play it safe.

His team was stung last week by the media's response to a press release pledging a consultation on women-only train carriages to tackle a rise in sexual assaults. In the blunt language of newspaper headline writers, the idea became a "plan" – as nearly all consultations inevitably do. Corbyn was baffled by the widespread criticism that followed and went on television to insist it was not policy.

Figures inside Labour HQ said the incident revealed Corbyn's "lack of confidence" in his own ideas. They are convinced that a party ruled by Corbyn will not be one ruled with an iron fist. When it comes to foreign policy, he is likely to remain firmly on the fence. In the past he has argued that Britain should withdraw from NATO altogether. But in recent weeks he has rowed back, telling one hustings that there "wasn't an appetite as a whole for people to leave" and that he would argue for the military alliance to "restrict its role" instead.

He has also wavered over the European Union. At a hustings in July he refused to rule out joining the Out campaign if David Cameron "traded away" workers' rights. But days later, under pressure from europhile Labour backbenchers, he insisted he had no plans to abandon Britain's membership. Labour insiders instead expect him to seek the views of party members on the EU through lengthy "policy debates". And if Cameron forces another vote on military action in Syria – which Corbyn has long been against – he will probably give Labour MPs a free vote rather than risk an embarrassing rebellion.

Corbyn himself spoke of a "bottom-up, not top-down" approach to leadership at Channel 4 News' hustings on Tuesday. He wants to put policy ideas to the members and supporters and not just the parliamentary party. But if he's unable to keep his bold ideas intact after discussion with all wings of the party, his loyal army of followers might start turning on him. "You can never satisfy people who think they're more left-wing than you," said one Labour staffer.

Meanwhile senior MPs are having to think seriously about whether they would serve in a Corbyn-led shadow cabinet. There are two possible approaches being discussed. One is to "isolate the leader", forcing him to appoint his old friend and ally John McDonnell as his shadow chancellor. Anyone who disagrees with Corbyn would not be on his front bench and would instead watch as he flounders on his own without support. The other option, which is looking far more likely, is an inclusive one.

Senior moderates would be encouraged to join Corbyn's front bench and help guide the party forward through choppy waters. Just as left-winger Michael Meacher became a minister under Tony Blair, so centrists should be able to serve under a left-winger. But Corbyn has to be willing to listen to different views – while old hands have to be ready to defend Corbyn's leadership on the TV and radio. "This is a test of his leadership skills and a test of whether Labour is ready to get on with the job of winning elections," one insider said.

Senior Blairites have markedly softened their tone towards Corbyn in recent weeks. On Sunday, Dame Tessa Jowell called on Tony Blair to stop attacking Corbyn and "get into the new activism". Similarly, shadow business secretary Chuka Umunna, who pulled out of the leadership contest early on, declared on Wednesday that "solidarity is key" and that Labour must "accept the result". Compare that with his comments in July, when he dismissed the veteran left-winger's views as not "a politics that can win".

Umunna, still seen as a future party leader, has joined with shadow education secretary Tristram Hunt to head up a new grouping of moderate party figures called Labour for the Common Good. But one thing is clear: There is no appetite for another 1981-style split. That is partly because neither Umunna nor Hunt is seen as influential enough to lead others away from Labour, although they insist they have no intention of doing so. The 1981 split, which saw the creation of a new, centrist party called the SDP (Social Democratic party) in reaction to an increasingly left-wing Labour, was forced by four big names: Roy Jenkins, Shirley Williams, David Owen, and Bill Rodgers. Today there seems to be some consensus that a long-term rebuilding job is needed rather than a crude split down the middle.

Some Labour figures are now convinced that if Corbyn wins power, he could well stay in place until the 2020 election. His ability to inspire a grassroots movement who can knock on doors ahead of crucial elections across the UK next spring is important. Whether he can win over enough voters – rather than party members – is another matter. "We've had shit leaders before and we've survived," a longstanding adviser said. "This is politics; anything can happen and we've got to do the best we can."