Britain loves opinion polling. And it guides the decisions of politicians and the media. But it's not completely reliable.

It doesn't take many people to sway a poll. Most good polls rely on a sample size of between 1,000-2,000 people.

A carefully selected sample of a couple of thousand people can be better than a slapdash survey of several million.

There's a sweet spot at which polling is simple enough to practically do, while also keeping an acceptable level of reliability. According to Anthony Wells of YouGov, and the author of the UK Polling Report blog, a bigger sample size doesn't necessarily mean a better poll.

Beyond that "you get to the point of diminishing returns".

What makes a poll worthwhile is how representative the sample is.

Each of us are individuals, and together, we make up lots of different tribes, based on our race, our gender, which class we fit into, what our political and personal beliefs are, even down to what kind of car we drive (or whether we can afford one in the first place). And they all need to be represented in polling at a similar level as they are in real life.

That can be done by who you select (sampling), and how you treat their views (weighting).

Sampling the right group of people to ensure you get a series of viewpoints that matches the wider populace is vital, as is giving their opinions the correct weight.

A good poll lives or dies on whether, through sampling and weighting, you've collectively got 1,000 or so people who represent the British public in all of the ways we know about.

Despite the small sample sizes, 80% of people trust polls to be honest and representative.

A survey by the Worldwide Independent Network of Market Research (WIN) and Gallup, a polling group, of 42,720 people across 47 countries, from Guatemala to Macedonia, the UK to the USA, found that globally, we're generally very trusting of survey results.

Britons, though, are more circumspect. A quarter of us said we distrust polls when asked the same question by ORB International. Scots are particularly wary, with 30% actively distrust polling results.

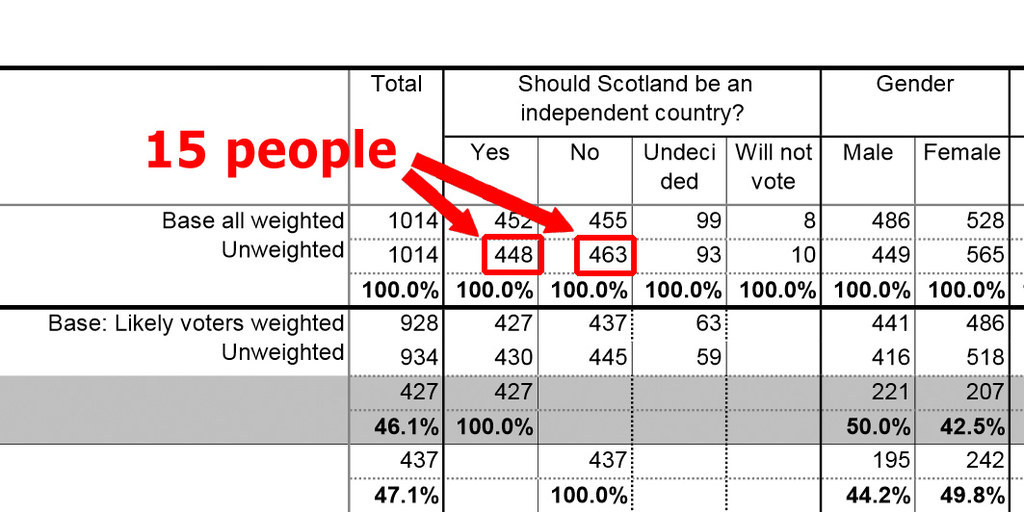

Scotland's a pretty good example of how polling works, and how few people are needed to change results – and the political narrative.

The recent independence referendum is a perfect example. referendum.

Both the 'Yes' and 'No' campaigns – as well as the huge army of journalists reporting on the Scottish Independence referendum – carefully watched polling. The 'No' campaign responded to a tightening of opinion polls by flooding the country with high-profile politicians near the end of the race.

The polls were so tight that in some cases, the gap between the 'Yes' and 'No' campaigns was less than the margin of error. The entire campaign was swinging on the views of just a handful of people's responses to polls.

In the end, pollsters correctly called the result of the referendum, but by and large understated the margin of victory.

Anthony Wells explains: "Scotland was particularly hard because normally, if it's a voting intention poll, our methods will be based at some point on a past vote. When something comes along like the Scottish referendum, you haven't got a previous referendum to go back and draw up methodologies and weighting from."

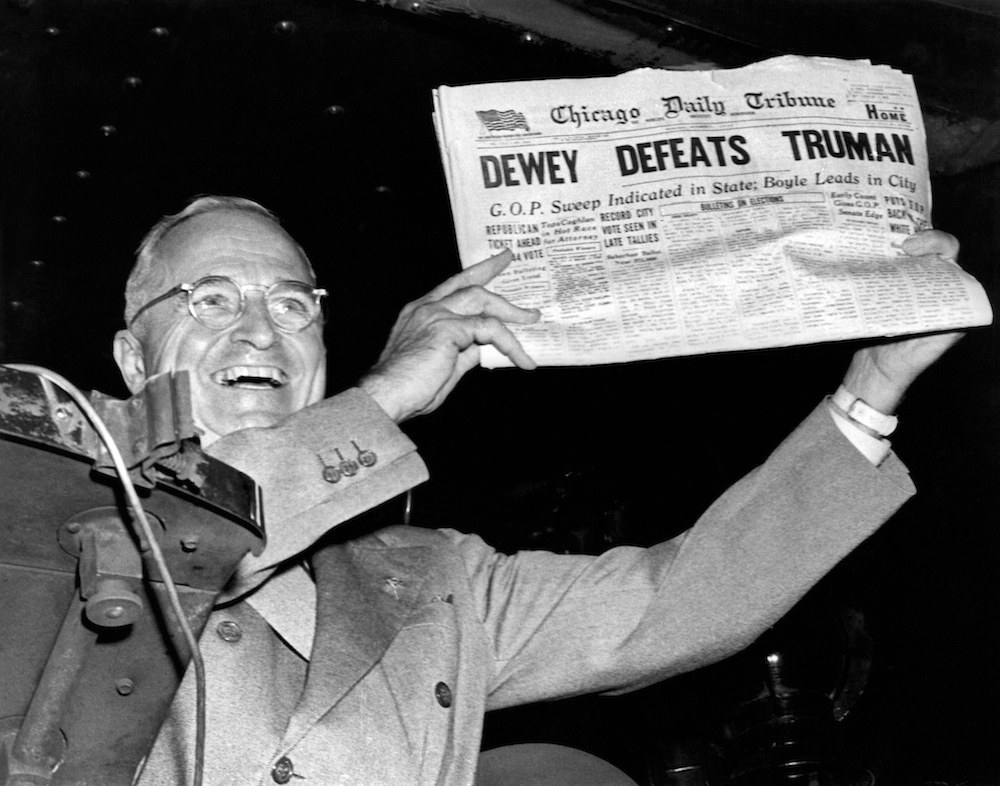

It could've been worse. This could've happened.

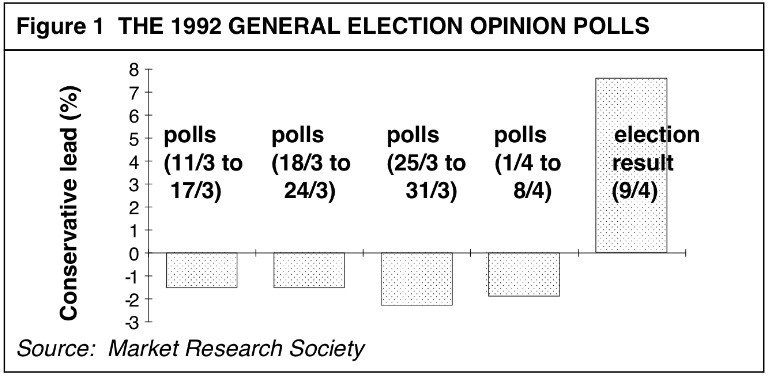

In the UK, there have been a couple of catastrophic failures.

But polls aren't infallible, because alongside small sample sizes, sometimes humans lie, or bluff their way through them.

A stubborn minority of people lie in polls. Well, that's according to polls of people asking if they lie in polls.

And just because someone responds to a poll, it doesn't mean that they're necessarily well-informed.

The headline-grabbing poll of 2,022 people carried out by YouGov asked people if they could recognise members of the Labour shadow cabinet. Among the names was Andrew Farmer, a politician YouGov made up.

15% of respondents said they had heard of 'Andrew Farmer', even though he doesn't exist.

That's a little #awkward.

So polling is tough to do, and we perhaps put too much stock in it.

"It’s a constant race to keep up with the British population, the British political system, and technology," he admits.

"You're only as accurate as your last general election. You're fighting to improve that and keep up with whatever has changed in the five years since."