Britain votes next Thursday, and the talk here is of an election reaching Israeli levels of complexity. Will the Scottish nationalists wipe out Labour in the north? Will the Ukippers come back to the Tories? What price will the Northern Irish unionists (remember them?) exact for their support?

There is another contest under way, however, a contest of mediums, pitting print – which is still perceived to be centrally powerful in Britain – against the internet. That test centers on the image of Labour leader Ed Miliband. The ferocious conservative press has devoted six months to trying to destroy his image, to painting him as weird and effete and unlikable.

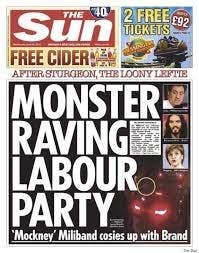

They do this with a bluntness unimaginable even in the most aggressive American print publications: On Monday, for instance, The Telegraph devoted its front page to a letter from business leaders urging voters to support Tory prime minister David Cameron. (BuzzFeed News' Jim Waterson reported that the letter's metadata suggested it was written by the Conservative Party.) The next day the Mail labeled "Red Ed" a "Stalinist" on its front page. On Wednesday, it wondered of an interview Miliband did with the radical comedian Russell Brand: "Do you really want this clown ruling us?" The Sun – Britain’s biggest paper, with 1.9 million readers to the Mail’s 1.6 million – went with “MONSTER RAVING LABOUR PARTY”.

A few months ago, the conventional wisdom was that Miliband wouldn't be able to withstand this treatment. The campaign had obvious bite. Even Miliband's friends would, in private, tell you that he was a little weird.

But something has changed. Despite the newspaper bombardment, Miliband’s popularity has been spiking upward, and his favorable/unfavorable numbers are the most improved of any party leader's. The polls remain stubbornly close – which, given the nature of Britain’s electoral system, has seen the bookies make Miliband favourite to become prime minister for the first time in the campaign.

Behind this appears to be another force shaping Miliband's image: the web. This hasn't been anyone's deliberate campaign. The New Statesman, Labour’s house magazine, endorsed Miliband only through gritted teeth. The Guardian, the left's dominant online outlet, has been mostly anti-Tory rather than pro-Labour. The rest of the web (including BuzzFeed's UK team) prefers mocking politicians to elevating them.

And yet, the digital Miliband is a bit easier to like. His online image has emerged just a couple key ticks over from the one shaped on Fleet Street. There, he's awkward. Here, he is – as one Milifan put it – adorkable. The most surprising evidence for this, uncovered by BuzzFeed UK’s Hannah Jewell, is the Milifandom itself – a small group of teenage girls who genuinely do treat him like a member of One Direction. The acerbic Sunday Times columnist AA Gill lamented recently that “the nerdiness isn’t a handicap on a computer. [The internet] is the home of blinky, wonky, impedimented, shy, over-cerebral oddballs.” Just like Miliband.

Miliband's media strategy has worked best on the web, from a modest but well-liked Instagram to a surprisingly viral radio interview about his ordinary life that was picked up and circulated on social media. But in the home stretch, his biggest hit may have been the interview with Brand. While right-wing national newspapers queued up to attack Miliband's decision to give an interview to the comedian, what finally emerged was a 15-minute, largely unremarkable chat about politics, not that different to the ones the same newspapers run all the time. Except that it has now been viewed more than a million times.

"A lot of the story of this campaign is how Miliband has completely defied the caricature of the Tories and their agents in the media," his American media adviser David Axelrod said.

Of course, Miliband could also blow it online – the British internet has spent most of today mocking his decision to etch his campaign promises on a giant stone tablet to be set up in the Downing Street garden. And there may, as in 1992, be a sudden Tory resurgence in the campaign's final days.

But his surprisingly strong showing has already suggested the end of a long era in which conservative newspapers were the most powerful force in shaping political opinion here, the days when Rupert Murdoch's tabloid could plausibly crow after John Major's 1992 victory, "It's The Sun Wot Won It."

Brand asked Miliband at one point during their interview about an old leftist dream: the suggestion that Murdoch's media ownership should be curtailed. Miliband demurred, then observed that Murdoch "is less powerful than he used to be." Thursday's vote will test that thesis.