I haven't watched a single second of the 2016 NBA Finals since the night of June 19th, when LeBron James, Kyrie Irving, and the rest of the Cleveland Cavaliers completed the biggest comeback in basketball history to defeat the Golden State Warriors — and break my fragile Northern Californian heart.

But that's not to say that I haven't seen the NBA finals since then. Watching occurs in the eyes, but sight happens in the brain. For about three hours after the end of Game 7, well into early Monday morning, I lay on my back, trying to sleep. But every time I closed my eyes, I saw the same thing: LeBron James striding across the court, Andre Iguodala swinging the ball around his hips, raising it to the rim, and then LeBron swatting it away.

I was able to repress every other memory from those cursed Finals — Kyrie's go-ahead three pointer to win it all, Draymond Green's series altering nut-shot. But LeBron still haunts my dreams, even though I haven't watched a moment of that game, or The Block, ever since.

Until Tuesday, that is. I was invited, along with many other reporters, into the bowels of the NBA store in midtown Manhattan to see FOLLOW MY LEAD: The Story of the 2016 NBA Finals, a roughly 25-minute virtual reality documentary produced by the NBA, Facebook-owned VR company Oculus, and the production company m ss ng p eces (it's really spelled that way). I strapped on a Samsung Gear VR and returned to my darkest hours, this time in full, immersive virtual reality.

The film, which its creators say is one of the longest continuous-narrative VR videos to be made using video footage, will be released for free by Oculus Wednesday.

It's style will be familiar to anyone who's watched HBO's 24/7 series, ESPN's 30 for 30, or an NFL Films documentary: a pseudo-heroic narrative from a celebrity (Michael B. Jordan) that relentlessly dramatizes the circumstances of a sporting event. The NBA and Oculus got lucky in this case, because the 2016 Finals had one of the most compelling sports narratives in years: the league's greatest player trying to vanquish its best ever team, in a rematch that also pitted the most culturally and economically ascendant region in the country — if not the world — against Cleveland.

"We wanted to prove you could do longform sports documentary in VR," Eugene Wei, the head of video at Oculus, told me. "We wanted to prove you could do longform in VR period. A lot of people say VR has to be short, so let's do something that's storytelling versus experiential."

The experience tends toward the cinematic — Wei said that the typical shot lasts six to eight seconds, which might be a little long for a traditional broadcast, but relatively short for VR.

So while Oculus, which sells its own VR gear, wants to see the virtual reality documentary evolve to compete and eventually surpass traditional video, the NBA wants people to get a new and exciting way to see a game. The league has already experimented with a VR broadcast, and the documentary is a way for tech-equipped fans "to have an opportunity to attend an NBA game," said league media executive Jeff Marsilio.

To film games, they had cameras behind the rim, on the scorer's table on the sideline, in the crowd, and cameras on the court to catch the post-game pandemonium.

So what does the Oculus version of the sonorous sports documentary give you, a virtual spectator there in the stadium? At first glance, you can look around and see a lot of people holding cell phones. And because for the most part, all the action is taking place on the court right in front of you, there isn't much benefit to turning your head left or right and peering into the stands.

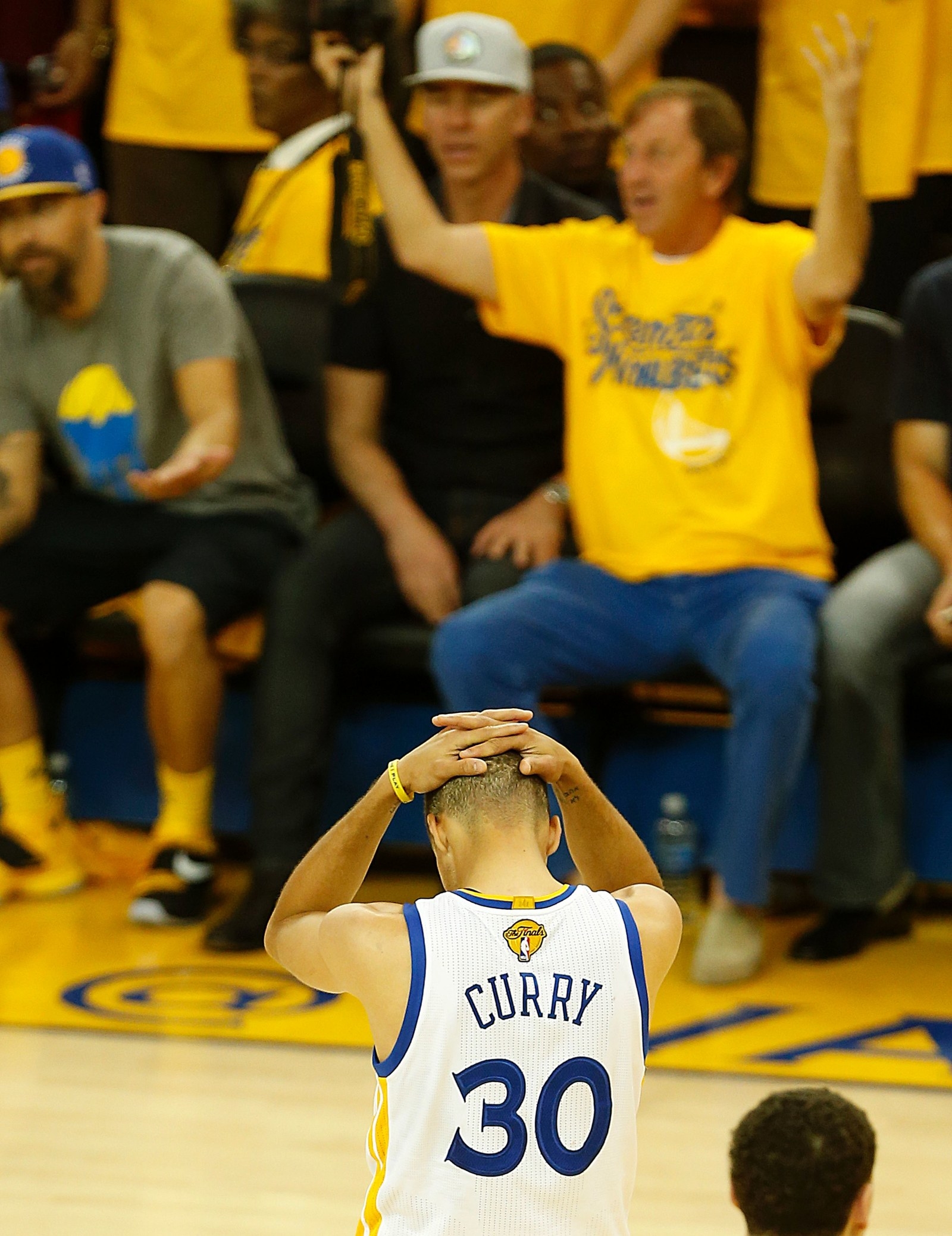

But when you do, it's a sea of cell phones, photographing and filming the action. When you see Steph Curry or LeBron James being interviewed after the game, you can look around to see members of the sports press, filming it on their cell phones.

And when you see LeBron walking off the court (the camera sits around his collarbone level, so you look down on Kyrie Irving and up at Timofgey Mozgov), you again see everyone with their cell phones filming. The irony is that thanks to the very technology that helps enable VR, the NBA will try to get fans to be as engaged as the fans actually at the games...looking at their phones.

But being able to pan to, say, Jay Z and Beyonce sitting courtside, provides the tantalizing prospect of just being able to turn your head and watch them during the lulls in the game.

Wei said this effect is typical, and what people actually tend to expect from a VR broadcast — a simulation of really being there. "The endpoint of VR is the sensation of reality," Wei said. "Anything that breaks the fourth wall accelerates your sensation of being there."

So even when a Warriors fan yells right into the camera, it's good for the experience — it's a way of avoiding what Wei calls the "Ghost Effect," named for the Patrick Swayze film where a man dies and comes back as a spirit who is physically present but is invisible to humans who aren't Whoopi-Goldberg.

When it comes to filming game action with the VR cameras, there are shortcomings for the time being: The cameras can be big and stationary, and the lenses are wide and don't zoom. It means the action can appear blurry if it's farther from the cameras.

These shortcomings are also barriers to having regular VR broadcasts of what Marsilio calls the "crown jewel" of the NBA: the live game. While they were able to get a lot of access for the special VR broadcast, the cameras would compete with space that's already taken up by regular TV cameras and photographers.

"It's like snowboarding in the early day of the medium, the learning curve is very steep," Wei said.

But at closer distances, issues like the blurriness are overcome by how thrilling it all is — the sensation of being there, the oohs and ahhs of the crowd, its silence and explosion right into your ears, with the shock of LeBron dunking right at you. If you could watch live games this way, it would blow traditional TV out of the water, and the NBA knows it.

"If we can bring the world truly courtside, live at the game, it would be the greatest thing we could achieve in VR," Marsillio said.