The halfway point between the election of President Donald Trump and the 2018 midterms has come and gone, and it still isn’t fully clear what Russian hackers did to America’s state and county voter registration systems. Or what has been done to make sure a future hacking effort won’t succeed.

US officials, obsessed for now with evidence that Russia’s intelligence services exploited social media to sway US voters, have taken solace in the idea that the integrity of the country's voting is protected by the system's acknowledged clunkiness. With its decentralized assortment of different machines, procedures, and contractors, who could possibly hack into all those many systems to change vote totals?

But the focus on how Facebook and Twitter were used to sow division in the US electorate has diverted attention from one of the weakest spots in the system: the gap between those locally operated voting systems that are well-protected by sophisticated technology teams and those that are less prepared. Russia knows those gaps exist and that a simple cyberattack can be effective against weak infrastructure and unprepared IT workers. Whether that can be fixed by 2018 or even 2020 is an open question.

Most states’ elections officials still don’t have the security clearances necessary to have a thorough discussion with federal officials about what’s known about Russian, or others’, efforts to hack into their systems.

Seven states still use all-electronic voting systems whose results cannot be verified because there is no paper trail.

And hundreds of US counties rely on outside contractors to maintain their registration records and update the software on voting machines. Some of those contractors are small operations with few employees and minimal computer security skills.

Many local officials are reluctant to seek federal help, worried about ceding authority to outside agencies.

“We’re not doing very well,” Alex Halderman, a renowned election security expert, told BuzzFeed News. “Most of the problems that existed in 2016 are as bad or worse now, and in fact unless there is some action at a national policy level, I don’t expect things will change very much before the 2018 election.”

On Sept. 30, 2016, 39 days before Election Day last year, the top election officials from most of Florida’s 67 counties hopped on an emergency conference call with federal authorities. The FBI and the Department of Homeland Security had intelligence on a specific threat, and they wanted every county in that battleground state to be on the same page.

The timing was hardly convenient. It was a 3 p.m. on a Friday, right before the weekend, and voting officials work hard in the lead-up to any election. The county supervisors had learned of the call only the night before, when Chris Chambless, then the president of the Florida State Association of Supervisors of Elections, received a call from the FBI and quickly sent a mass email to his colleagues.

The call, led by representatives from the FBI and the DHS, lasted nearly an hour, participants recalled to BuzzFeed News, though the federal officials’ willingness to answer county officials’ questions was limited because none of those in Florida had security clearances.

The feds had several lists of IP addresses that might target Florida election systems, the FBI agent said, so each county should be sure to have their IT staff block them all. And everyone should take advantage, DHS reminded them, of its standing offer to all US election offices for free “cyber hygiene” vulnerability scans. Some Florida counties had already taken DHS up on the offer, but many preferred to rely on their own IT staffs.

For some county officials, this was an example of the system working properly, of federal and county government employees working together to ensure the country’s elections are secure from hackers. There isn’t enough time or resources to give a security clearance to a voting official in every county in the US, so a tight-lipped warning from the feds, accompanied by a specific recommendation for what actions they should take to secure their systems, should be plenty.

“I think it was very effective,” Chambless, who is also the supervisor of Clay County elections, told BuzzFeed News. “I think that all supervisors were extremely diligent in those lists of IP addresses. At any time, if we were to notice any type of intrusion with internal capabilities, there would have been urgent communication within our own state. So we took it very seriously. We used every resource that was available to us.”

But not everyone on that call came away feeling safer. “They couldn’t describe them to us, because no one had security clearance,” Palm Beach County elections supervisor Susan Bucher told BuzzFeed News. “We still don’t know. They told us nothing. They told us, just if you want your system scanned, get in line.”

DHS made one conference call in 2016 to alert Florida officials to possible hacking. Many officials didn't take part.

Bucher understood DHS’s offer to scan her county’s systems to be a pointless one, since it would take six weeks due to the backlog, and therefore wouldn’t be completed until after the election. (The FBI and DHS confirmed the call happened, but declined to provide specifics of its contents. A DHS spokesperson said that its hygiene scans usually take a few days, and that only 36 local election offices across the country requested the service before the election.)

But Bucher conducted the election with confidence anyway because Palm Beach’s voting machines, like most counties' across the US, don’t connect directly to the internet, though the Palm Beach database of voter registration information, which sends daily updates to the state division of elections, does. Bucher instructed her IT staff to be on high alert.

“We verified we had no penetration anywhere, nor could they find a backdoor,” she said.

Some counties who were on the invitation email, which was obtained by BuzzFeed News, took away even less from the FBI’s warning. “I remember the call but I can’t recollect exactly, I can’t quote what was said,” said Shirley Knight, the elections supervisor in Gadsden County, Florida’s only majority-black county, where Democrats outnumber Republicans 4 to 1 and Hillary Clinton received 67% of last year’s presidential votes. If Knight took action, she doesn’t remember it. “That was a year ago,” she said.

Others don’t remember the call at all, the only all-hands warning from the federal government to Florida counties in the lead-up to the election. Wakulla County elections supervisor Buddy Wells said he spent Sept. 30 conducting his usual local outreach: bringing voting equipment to a nearby elementary school to conduct a mock election for students so that they’ll be less intimidated by the process when they’re old enough to vote.

He wasn’t concerned about cyberattacks, he told BuzzFeed News, because he’s long opted for DHS’s free scanning service, which every Monday sends him a report, dozens of pages long, detailing possible threats.

“I’ve gotten one every week ever since I started,” he said proudly. “I’ve been negative every time.”

A few weeks before that Florida call, then–FBI director James Comey reassured Congress that the election system itself was safe from hacking because it’s “clunky as heck.” A presidential vote is conducted across well over 100,000 precincts, in 3,007 counties, by 50 state governments. A foreign adversary would have to find multiple exploits in order to significantly affect the national vote.

But in the aftermath of last year’s vote, it has become clear that the sheer complexity of the system is no reassurance that it can’t be exploited by a determined hostile power. Halderman, the election security expert, says that just because it didn’t happen last time — or in the voting completed Tuesday — doesn’t mean it won’t.

“It’s only a matter of time, if we don’t have coordinated national action, until a major US election is disrupted, or even its outcome changed, by a foreign nation-state in a cyberattack,” he said.

To this day, DHS points to the fact that it’s never found evidence that vote tallies were changed as reassurance. But Russian hackers made at least two multistate attacks on voter registration systems, and it’s unknown if there might have been others. It’s also unclear how many states, like Florida, were particularly targeted in the weeks before the election.

In both of the known attacks, Russian hackers started with routine, though still effective, hacker methods. One of them, according to an NSA analysis compiled in May 2017 and leaked to the Intercept, was attempted spear-phishing and simple email “spoofing,” in which someone registers an email address similar to one a victim would trust, tricking them into handing over credentials or downloading a malicious file.

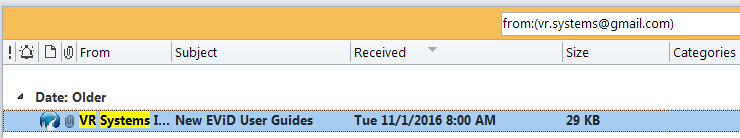

According to the leaked analysis, the hackers sent malicious emails that falsely appeared to come from VR Systems, a leading US voting equipment company, to county IT workers. They tried the same trick using spoof accounts mimicking two other manufacturers.

It’s unknown, at least publicly, who those other US manufacturers were, or which states were targeted. The NSA report says that campaign targeted about 100 VR Systems customers who worked for the government. It’s also unclear if any of them fell for it, but several Florida county IT workers who told BuzzFeed News they were targeted said that email was caught in their spam filter or by their antivirus program.

The second known attack was what DHS has described as the scanning of 21 states’ voter registration systems. The attackers penetrated Arizona’s and Illinois’ databases but didn’t change any records, state officials and DHS have said. The attack tactic used was so simple, a former senior DHS official told BuzzFeed News, that investigators initially didn’t think a nation-state was involved. It was only later that Russia was identified as the likely culprit.

The results of such a violation of voter registration records could have been as devastating as changing actual votes. If hackers targeted a heavily partisan county to falsely show that 5% of eligible voters had already voted absentee, for example, it would wreak havoc on Election Day and block thousands of voters from casting ballots — a game changer in a close vote.

“Assuming that the altered data was not detected before the election, voter registration data that is changed could cause disruption at the polls on Election Day,” said Marian Schneider, president of Verified Voting, a nonprofit that monitors election equipment security.

Even if it were caught before an election, such vote vandalism could still keep people from casting ballots.

“Rolling back to an accurate database will take time, and resolving the disputed provisional ballots could also take time and cause a delay in certifying the election results,” Schneider told BuzzFeed News.

The primary way to stop that kind of interference — to get intelligence of such attacks to trickle down to county workers — is, of course, through a series of government bureaucracies. A government-affiliated nonprofit devoted to promoting cybersecurity, the Center for Internet Security, runs the Multi-State Information Sharing and Analysis Center (MS-ISAC), which ferries technical information, particularly DHS and FBI warnings, among government organizations that sign up.

Every state and US territory is an MS-ISAC member, though local governments, such as the counties that actually run elections, must sign up themselves and many have not; only 62% of US residents live in jurisdictions where the local government has registered, a spokesperson said. Most states choose to use MS-ISAC’s antivirus program, called Albert, which continually scans member computers and reports threat information back to DHS. It was Albert that in summer 2016 caught a malicious actor trying to perform what are known as SQL injections, an entry-level hacker method for breaking into online databases, on state voter registration lists.

Through MS-ISAC alerts, DHS contacted state IT workers to warn them which IP addresses were attacking, but didn’t mention — or didn’t yet know — that the actors were believed to be agents of the Russian government. In most cases, those state IT workers took steps to secure their networks, but SQL injections are more in line with the toolset teenagers, not intelligence agencies, would use, so word of the attempts didn’t reach the respective secretaries of state who generally have statewide responsibility for voting.

Nearly a year after those MS-ISAC alerts, Jeanette Manfra, a DHS official, admitted in Senate testimony that Russian government hackers had targeted 21 states. But it wasn’t for months after that, after mounting pressure from individual secretaries of state and Virginia Sen. Mark Warner, that DHS set up individual calls to briefly tell the top election officials in those states that Russia had tried to scan their databases.

Those calls marked a breaking point in a year of particular tension between DHS and individual state officials, who often see conducting elections as one of their most important duties. For example, before the election, Georgia Secretary of State Brian Kemp denounced federal intrusion after he noticed a federal IP address on his network and erroneously concluded that DHS had made an “unsuccessful attempt to penetrate the Georgia Secretary of State's firewall.” (The IP address actually belonged to a Federal Law Enforcement Training Center employee who was looking at the Georgia firearms registry.) Kemp's office didn't respond to a request for comment.

A month later, then–DHS chief Jeh Johnson, in one of his final acts in office, designated election systems as “critical infrastructure,” making it easier for federal agents to offer physical and cybersecurity aid to people who work in the sector, but also stoking fear among state government employees that the federal government wanted to infringe on their ability to conduct independent elections.

“One of the big problems is the same problem everywhere in cybersecurity, which is that they can’t hire enough people.”

State and local officials should have long ago accepted federal help, a former DHS senior official told BuzzFeed News, but DHS didn’t frame its offer in a way that made it easy to accept.

“Anyone who gets their fingers on these systems at the local level is also installing printers,” the official said. “Instead of the conversation being about ‘is there anything we can do to help you guys?’ it appeared like a land grab. Or worse, if you’re one of those paranoids down in Georgia, it looked like DHS was somehow trying to federalize the elections process.”

One problem with small government bodies, just as with the private sector, is that it’s hard to hire enough quality security staff, said former White House liaison to the Department of Homeland Security Jake Braun, who’s been urging members of Congress to allocate money for election security.

“One of the big problems is the same problem everywhere in cybersecurity, which is that they can’t hire enough people,” Braun told BuzzFeed News. Barring that, he said, states need machines that leave a paper trail as soon as possible. “If they could just make all the states go to paper and risk-limiting audits, that would be a huge step forward,” he said.

A few weeks after DHS’s admission, tensions began to cool. On Oct. 16, eight secretaries of state, representing their national association, met with DHS and the Election Assistance Commission to form yet another group, the Election Infrastructure Subsector Government Coordinating Council, which is referred to by the initials GCC for short.

“This council is designed to improve threat information sharing between the federal authorities and the state and local election officials,” Vermont Secretary of State Jim Condos said in a statement. “We had the right people in the room for candid conversations about what did and did not work in the past so we can move forward and get this right.”

One major hope of the GCC is to avoid confusing situations such as the last-minute Florida conference call, or the drama surrounding DHS’s refusal for months to identify which states it had determined had been attacked.

But the GCC has a major problem, say election officials: It moves at the speed of government. The group is currently focused on helping to create an election handbook, a best practices guide that state and federal authorities can agree to. But even that’s slow: Members are still deciding who should have a say in the book. They hope to have it released by the end of 2017.

Officials also are hoping for smoother federal and state cooperation by ensuring that every state has at least one employee with a security clearance to receive sensitive federal warnings. DHS has already tried to implement such a program. Some states have gone further, hiring people who already have a clearance. West Virginia, for example, recently hired Evan Pauley, who received top-secret clearance working as a cybersecurity analyst with the Air National Guard, to be a cybersecurity specialist in its secretary of state’s office. And the hiring practice will likely soon become law for each of the 50 states, as Warner wrote a provision into the Senate Intelligence Authorization Bill that makes DHS grant a clearance to an employee in each state.

One of the biggest pushes is persuading states to make sure they are using safe voting machines and registration systems. Until 2015, copyright regulations largely prevented independent research into US voting equipment. Then those restrictions were lifted for three years, leading to the discovery that amateur hackers can easily decimate voting equipment security — highlighting the importance of updated and secure equipment that leaves an auditable paper trail.

States’ responses to the discovery of vulnerabilities in voting equipment have varied.

Election experts give high marks to Virginia, which recently became the last state to decertify the infamous WINVote touchscreen machines, which in the right circumstance could allow a hacker sitting in a nearby parking lot to exploit the equipment via the device’s superfluous Wi-Fi capability. Prompted in part by press reports that hackers at the DefCon cybersecurity conference could easily hack both AccuVote TSx and iVotronic machines — both still in use in parts of Virginia — the state proclaimed this fall that it would use only paper ballots that are then electronically scanned. The first election to feature that requirement was the just-completed governor’s election.

“If there had been an issue on Tuesday, and it was a super-close election, and there was a question about the equipment in one of the precincts, would we be able to say with confidence that the results were accurate? I think for us, we said we couldn't do that [with the old equipment],” Virginia Department of Elections Commissioner Edgardo Cortés told BuzzFeed News.

The new equipment worked without a hitch, Cortés said. “We did have localities that were using new equipment for the first time, and it went really well for them,” he said. “They didn’t have any issues on Election Day. Everything went really smoothly.”

Virginia and Iowa have both adopted strong postelection audit laws, another practice experts say helps inspire confidence. Michigan has replaced most of its outdated equipment, Schneider said, and will soon join Rhode Island and Maryland in eliminating all paperless voting machines.

Arkansas, Delaware, Georgia, Louisiana, New Jersey, North Dakota, and South Carolina still use voting machines that don't leave a paper trail.

The Election Assistance Commission, which some states use to choose which machines they can purchase, has created new guidelines. Voting machines must now produce “readily available records that provide the ability to check whether the election outcome is correct,” which Lawrence Norden, deputy director at NYU Law School’s Brennan Center’s Democracy Program, reads as a specific reference to paper.

Still, other states have done little to nothing to keep up with changing security standards.

State legislatures in Arkansas and North Dakota recently rejected efforts to replace paperless voting machines. South Carolina, whose voting machines provide no paper trail, has abandoned plans to replace those machines; Nikki Haley had pressed for the replacement as governor before she was nominated to become Donald Trump’s ambassador to the United Nations.

New Jersey, Delaware, Georgia, and Louisiana also use voting machines that provide no paper trail — and have no plans to change that.

On the whole, Congress has been quiet on the issue, though there are rumblings that it might step in to help states fix their equipment needs. One bill that voting experts hope will push states to get rid of paperless voting machines was introduced in September by North Carolina Republican Rep. Mark Meadows and Rhode Island Democratic Rep. Jim Langevin. It would force states receiving federal funds to purchase voting machines to buy only ones that leave a paper trail. South Carolina Republican Sen. Lindsey Graham and Minnesota Democratic Sen. Amy Klobuchar have proposed similar legislation as an amendment to the 2018 National Defense Authorization Act.

Both Norden and Halderman say for the first time they have hope Congress will act.

“There does appear to be bipartisan interest on this issue in Congress for the first time in a long time,” Norden said.

“It’s such a commonsense thing to do, and such an urgent thing to do,” Halderman said. “I know that there is a lot of contention in Washington right now about a lot of issues, but I think safeguarding the foundations of our democracy is one that, fortunately, many people agree about.” ●