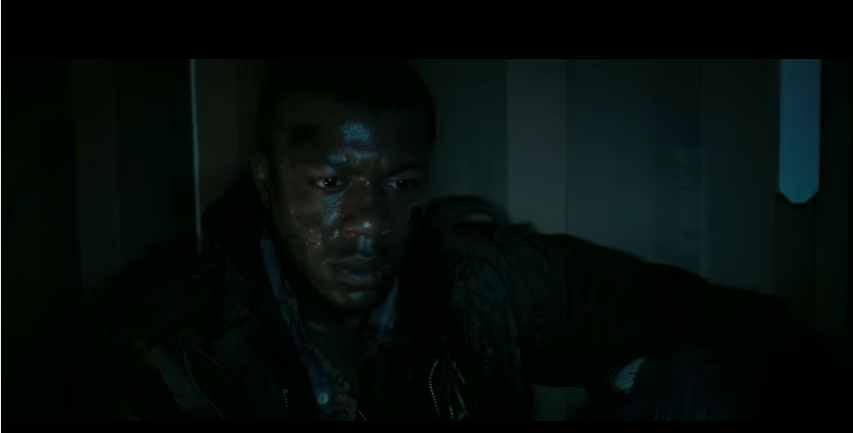

In a pivotal scene from Jordan Peele’s new horror film, Get Out, Chris (Daniel Kaluuya), a docile photographer and the movie’s protagonist, comes to after being rendered unconscious by hypnotherapy. Tied up in an old club chair in a suburban den in upstate New York, his hands claw the leather armrests as he struggles to come to terms with the fact that his white girlfriend’s wealthy family, who appeared liberal and well-meaning, are holding him against his will. It’s a moment that depicts something rarely shown to a broad cinematic audience — a black man subdued by his fear. The terror of Peele’s film arrives most powerfully in the helpless resignation Chris conveys, the psychological exhaustion, the recrimination for not trusting his initial fears about coming to the countryside in the first place, a fear black viewers recognize immediately as their own.

If the choice of suburban setting Peele stages for us — wall-to-wall carpeting, pastel wallpaper, vanity mirrors — feels familiar, that’s because it is. In purposely recalling the whites-only, suburban horror of films like The Stepford Wives (1975), Halloween (1978), Poltergeist (1982), and Nightmare on Elm Street (1984) — and placing Chris squarely in their setting, Peele confronts audiences with an image foreign to the American imagination: black men terrified.

Horror films have a unique history of exploring the black presence in America since their creation: In the 1930s, films depicted black people as emblems of the uncivilized world, culminating in 1933’s King Kong; 1932’s White Zombie played on another popular trope, fear of black religion, as vodun turned unsuspecting white people into zombies. In the 1940s, black people became convenient opportunities for comedic relief, exploiting minstrel tropes in Spooks Run Wild (1941), where one black character says to another, “The next time you come out of the dark, put a coat of whitewash on, will ya,” to which his co-star replies, “I’m so scared, I’m turnin’ white now.”

In George A. Romero’s classic 1968 film Night of the Living Dead, the murder of Ben, the black character, by a mob of white vigilantes who think he’s a zombie — even though he spends most of the movie protecting people from zombies — serves as the quintessential political message of the civil rights era: black men endangered by senseless white violence. But making overt political statements about race through horror movies all but disappeared by the late ’70s, when commercial filmmakers began establishing the suburbs as the exclusive setting for horror and stayed there for the next three decades. Black characters were often confined to filling a quota in ensemble casts, or waiting until a franchise chose to move its narrative to the inner city — see Friday the 13th Part VIII: Jason Takes Manhattan (1989) or Children of the Corn III: Urban Harvest (1995). The horrors rumored to take place in black ghettos were much too real for something fantastic or supernatural to seem plausible. (Except in the case of 1992’s Candyman, which is set in the Cabrini Green projects and depicts the titular villain as the son of a former slave.) Instead, black people were relegated to films where they engaged in the gun-toting, crack-slanging, and welfare-check-cashing that was apparently their exclusive province in that day.

Not until films like the Purge trilogy and Peele’s Get Out have black men been allowed access to the countryside, and depicted as vulnerable — a privilege they are rarely afforded in real life — rather than caricatured by the associations usually attached to their mythic bodies or the rumors of their sexual prowess. These films grant black men a rare aura of grace precisely by staging their moments of vulnerability in a suburban landscape, traditionally depicted as pristine and white. By doing so, they dismantle nearly three decades' worth of associations that have rendered black men denizens of lawless urban spaces, undeserving of an empathetic gaze. They also remedy the lack of imagination that so often leads to the death of real-life unarmed black men (and children) like Trayvon Martin, Michael Brown, and Joe McKnight.

Many depictions of suburban life during the ’80s — John Hughes’ Sixteen Candles (1984); The Breakfast Club (1985); and Ferris Bueller’s Day Off (1986); Steven Spielberg’s ET (1982), and Robert Zemeckis’s Back to the Future (1985) — do not feature black characters, a creative choice that ultimately quarantined blackness into the urban zones many white families had fled. This fantasy resulted in “an affirmative construction of Whiteness through racial segregation or exclusion,” Robin R. Means Coleman, a professor of communications and African-American studies at the University of Michigan writes in Horror Noire, a book that chronicles the presence of black people in horror films since the early 20th century. In film, suburbs prided themselves on being “race- and class neutral [but were] critical in distinguishing White from Black, the middle class from lower class, the suburban from the urban.”

Depictions of suburban life in mainstream cinema led horror-film directors to follow suit, seizing on the chance to riff on the manicured perfection of the suburbs — a place seen as idyllic, inviolable to blight, or abuse, or anger — and to dramatize the horror of things going wrong. In films like Halloween, Nightmare on Elm Street, and even The ‘Burbs (1989), the white victims were always terrorized by white monsters. And watching so many white boys die — and their white girlfriends in even gorier fashion — instructed viewers to protect the sanctity of those bodies in real life.

Watching so many white boys die — and their white girlfriends in even gorier fashion — instructed viewers to protect the sanctity of those bodies in real life.

For a black character to gain access to those spaces — screen time, a line of dialogue, the concern of their castmates — they were first required to relinquish any visible tie to a black community beyond themselves. Often these characters were narratively orphaned, left with no visible black parent or guardian, denied the company of a black friend or community, solely visible onscreen to enjoy the largesse of a benevolent white friend, until it was time to come to a white person’s aid, like Dick Hallorann in The Shining (1980), or to bring the fight to the monster, as Roland Kincaid did in A Nightmare on Elm Street 3: Dream Warriors (1987). One notable exception was Wes Craven’s The People Under the Stairs (1991), which centered around the plight of a black family suffering the threat of displacement at the hands of depraved white landlords. And yet the decade’s tropes still infect the movie — all the horror takes place at the landlord’s home, a white girl becomes the object of the protagonist’s heroic efforts — as though the film demanded these elements to make it appealing to audiences at the time.

Horror films constantly reinforced the concept of the white body’s vulnerability, and subtly advised their audiences to treat only those bodies with concern. Meanwhile, for black characters, and by extension, black people, if no one ever saw you scream, tremble, or bleed, they never learned to see you as human. In the aughts, black characters in horror films were either disposable, not worth depicting at all, or rendered racial amnesiacs when it came to issues that would concern any black person in real life — a contrast to the progressiveness of Night of the Living Dead decades before. In this way, black characters have appeared in horror films, yes, but rarely as black people. Black female singers like Brandy (1997’s I Know What You Did Last Summer) or Kelly Rowland (2003’s Freddy vs. Jason) settled into the role of the final girl’s best friend. Black men like LL Cool J (1998’s Halloween H20) and Ving Rhames (2004’s Dawn of the Dead) were often cast as security guards, and so exploited a muscular physique, an aggressive disposition, a misguided hero complex, and a handgun. But a fully realized black person — connected to a black family, in possession of black friends, or written into a narrative that gave some attention to black concerns — was nonexistent.

What makes The Purge, a 2013 home-invasion horror film written and directed by James DeMonaco, such a departure from the suburban horror genre is the way that it treats its black characters. An unnamed black man, played by Edwin Hodge, flees onto a leafy suburban street, pursued by a group of wealthy white local teens bent on killing him. He finds refuge in a white family, the Sandins, who live on the same block. Charlie Sandin, the youngest child, unlocks the front door, allowing the stranger access to the house and protection from his pursuers. The Purge makes use of those suburban tropes established in the ’80s and early ’90s by showing the suburb’s native inhabitants as monstrous, intent on killing Hodge’s character for their own benefit and depicting Mr. & Mrs. Sandin’s immediate fear that in their home, the “bloody stranger” is a sexual threat to their daughter. The movie anticipates that the audience will make these assumptions, using that complicity to bring attention to the character's race in order to demonstrate how his blackness endangers him. It then asks the film’s white characters to put themselves at risk in order to protect the humanity of Hodge’s character. This time, suburban white people must devote themselves to ensuring the safety of a black man; in fact, it becomes the film’s central moral concern.

Visually striking, well-acted, and adept at playing for both pathos and laughs, Get Out reminds us what horror can accomplish.

The Purge continues the theme of early ’80s slashers, as white people are forced to reckon with their own monstrous nature after pinning themselves inside structures — the literal metal barricades Mr. Sandin sells as a security salesperson — which provide an illusion of safety that will not hold. The franchise itself even indicates some wrangling over the changing relationship to the way characters such as Hodge’s will be viewed, listing him in the first film’s credits only as the “Bloody Stranger,” but allowing him to survive. He eventually becomes the lone interlinking star in the Purge franchise, later given the name “Dante Bishop” in The Purge: Anarchy, as his role in the franchise grows and his blackness is acknowledged. He quickly becomes the film’s moral compass.

But the Purge films, especially The Purge and its sequel, The Purge Anarchy, seem most interested in confronting white male protagonists with the moral problems that arise when their nuclear families are endangered. Black characters are the agents meant to solicit benevolence from their white saviors, and so their plight and the cost of the horror they’ve experienced are less vital to the concerns of the movie.

This is key to understanding the necessary departure Get Out makes, moving from what Coleman calls a “Blacks in Horror” film to a “Black Horror” film. Visually striking, well-acted, and adept at playing both for pathos and laughs, Get Out reminds us of what horror can accomplish. Black characters are no longer present as catalysts for something in the plot, but rather their terror becomes the explicit concern of the film. In fact, Chris is even granted a connection to a larger black community. His friend, Rod, played by Lil Rel Howery, intermittently calls Chris to jokingly check in on him. And watching Chris’s torture scenes is crucial to understanding Get Out’s poignancy. In a recent interview with BuzzFeed News, Peele talked about how he intentionally wanted to disrupt the historically male gaze of the horror tradition by making his film’s lead victim male. Seeing a dark-skinned, big-eyed black man convey heartrending sadness over his betrayal, fear, and pain is a powerful reconfiguration of horror’s traditional victims. It is the dramatized need for a black man’s rescue, presented without question, that is radical.

Get Out arrives as instances of terrified black men have bled into life offscreen, exposing the lack of images that sympathetically portray such men. The recent film depictions of black men in the suburbs being subjected to violence reflect anxieties surrounding real-life violence enacted on black men in such spaces. The killings of Joe McKnight, Trayvon Martin, and Michael Brown all took place in suburban environments — places they maintained only tenuous connections to — where they were pursued by white people acting out of terror and empowered by guns.

It's as if something in our culture has not readied us to see black men in a posture of fear.

Place becomes important as the presence of black men in such environments seemed to make them more monstrous, and more deserving of the horror imposed on them by their murderers. In his grand jury testimony, officer Darren Wilson described the feeling of grabbing Michael Brown as “like a five-year-old holding onto Hulk Hogan. That’s just how big he felt and how small I felt just from grasping his arm.” Wilson continued by describing Brown’s “intense aggressive face,” saying that “the only way I can describe it, it looks like a demon, that’s how angry he looked.” Perhaps what also unites these stories is the audacity in the killers’ ability to deny wrongdoing. It’s as if something in our culture has not readied us to see black men in a posture of fear, as though films have consistently taught audiences who’s the natural killer and who’s the obvious victim.

More terrifying perhaps is the narrative of confusion these white men seem to be suffering from, as if their terror is a result of a reliance on outdated stories, stories horror films often propagated. Their bewildered faces before juries considering their guilt seem to be troubling over the following questions: I escaped the city in flight from bodies like yours. Why are you even here? In a startling reversal, these white men have become the monsters they profess to want to protect their communities from, the lone lesson from suburban horror tales so few seem to have learned.

Get Out picks up the echoing shotgun blast that closed Night of the Living Dead, creating a vehicle for socially relevant commentary to reach broader audiences through genre film. In Get Out, Peele has crafted a film that could shatter the mirror that reflects only our best selves back to us. Horror’s potential is boundless, as the genre actively works to unsettle viewers who have grown too comfortable with their reflected image.