It used to be that there was no greater accomplishment in the music industry than a best-selling album, and that hit singles were a means to an end.

In the album era, from roughly the late 1960s to the early 2000s, record labels soared on the backs of albums — from the Beatles and Pink Floyd to NSYNC and Eminem — generating tens of billions of dollars in annual revenue globally by selling what was then viewed as the pinnacle of artistic achievement for working musicians. The singles business, which followed the 7-inch disc format into decline after the advent of the LP, was both commercially and artistically lesser — real artists made albums, the industry said, and for a long time consumers went along.

That dynamic, long challenged by the unbundling of the album on platforms like iTunes, YouTube, and Spotify, was finally put out to pasture last November, when Billboard announced that it would retool its influential albums chart, the Billboard 200, to account for individual streams and track sales for the first time in its history. In a climate where fewer and fewer people seemed interested in buying albums, opting instead to access them on streaming services or download select tracks from iTunes, Billboard (where, full disclosure, I was a reporter until a year ago) pivoted to capture more modern forms of consumption, adding up any 10-track downloads from an album, or 1,500 streams — figures that approximate the revenue of an album sale — and treating them as good as one.

In the six months since it debuted in early December, the new Billboard 200 has eroded the barrier between what were effectively two industries — one for albums and another for singles — and legitimized a generation of artists for whom albums have never been more than one of many movable parts that make up a career.

“On some level we have to get away from our bias toward the album as the defining product of music,” said Jim Roppo, EVP of marketing at Republic Records, home to artists like Ariana Grande and Lorde. “It isn’t anymore.”

In a fiercely competitive industry where bragging rights and accolades are precious currency, the Billboard 200, which debuted in 1956 and was last overhauled in 1991 with the introduction of SoundScan point-of-sale metrics, has long been the yardstick by which all popular artists are measured. For major labels, a high debut on the chart is a vindication of months or years of investment, and provides a critical jolt of momentum in the press and other business dealings. A poor showing on the 200, on the other hand, leaves a painful and visible blemish on everyone involved.

“On some level we have to get away from our bias toward the album as the defining product of music. It isn’t anymore.”

Changing the formula of the chart has had a material effect on its content, making it more inclusive of albums that spawn hit singles, irrespective of whether those singles inspire album sales. Since the new chart launched in December, there have been three instances where the top-selling album in the country has failed to claim the No. 1 spot, according to Billboard, succumbing to other projects with a stronger mix of album sales, track sales, and streams.

The first such instance happened in February, when Taylor Swift’s 1989 snagged its 11th week at No. 1 despite being outsold that week by the 53rd volume of the Now That’s What I Call Music compilation series. The second came a month later, when the Empire soundtrack bested Madonna’s Rebel Heart for the top spot. Rebel Heart outsold Empire 116,000 to 110,000, but Empire had the higher cumulative point total thanks to an additional 17,000 track equivalent albums sold (TEA) and 3,000 streaming equivalent albums (SEA). Madge’s album had more modest TEA and SEA sales of 4,000 and 1,000, respectively.

The third and most dramatic instance of track sales and streams helping to trump album sales came in April, when the Furious 7 soundtrack climbed to No. 1 in its fourth week, fueled by cresting sales of the runaway hit single “See You Again” by Wiz Khalifa and Charlie Puth. The better-selling album that week, by a substantial 30,000 copies, was pop-punk band All Time Low’s Future Hearts; but “See You Again,” which sold a gargantuan 464,000 downloads, ensured that Furious 7 blew it out of the water.

Since the new chart launched, there have been three instances where the top-selling album in the country has failed to claim the No. 1 spot.

If you’re All Time Low, or Madonna, or the owners of the Now franchise, the new multi-metric ranking system probably feels about as welcome as a blow to the stomach. And, indeed, the revamped chart has its fair share of critics. Rich Bengloff, president of the American Association of Independent Music, a trade group whose members include All Time Low’s label Hopeless Records, said the new Billboard 200 disadvantages artists who make albums that aren’t buoyed by hits.“If just one single can overwhelm album sales, then it becomes a hits-driven chart, when it’s supposed to reflect bodies of work,” said Bengloff. “We already have a singles chart.”

But Billboard argues that including track sales and streams in the Billboard 200 makes for a more accurate portrayal of what albums are truly popular in the digital age. Only counting album sales (down 11% last year, 8% the year before) is an increasingly myopic way of looking at music consumption as streaming activity has exploded — a trend that may be dramatically hastened with the arrival of Apple Music. And since streaming services currently collect only bulk data, and don’t track how many songs a person streams from an album, there’s no perfect analog to an album sale in the streaming world. Whether the listener is interested in venturing beyond the song they heard on the radio or a blog is moot — all that counts is that they’re listening.

“Yes, there are albums that benefit more than others from the inclusion of track-equivalent albums and streaming-equivalent albums on the chart,” said Keith Caulfield, associate director of charts at Billboard and manager of the Billboard 200. “But I think those really are the most popular albums because of the hits that they’re generating and because of the way people are consuming them and listening to them and buying them.”

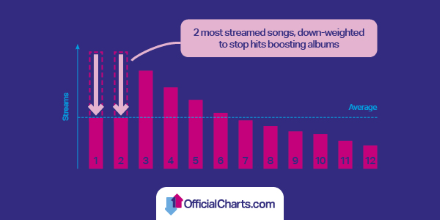

In the U.K., handwringing over the inability to distinguish whether users of streaming services were really listening to albums or just the hits prompted the Official Charts Company to devise a complex new formula for its own album rankings, announced in February. The formula, cited favorably by Bengloff and his cohorts, effectively neutralizes the impact of albums with one or two songs that are wildly more popular than the others. While he called the OCC’s methodology “interesting,” Caulfield said Billboard has no plans to take similar methods with its own chart.

Though tracks and streams now count toward the Billboard 200, the upper ranks of the chart have still mostly resisted primarily singles-driven interlopers — making cases like the Furious 7 soundtrack exceptional. Florence and the Machine, this week’s No. 1 with How Big How Blue How Beautiful, and blues rockers Alabama Shakes, who had a No. 1 debut in April, won the field handily despite earning negligible points from tracks and streams, proving that, for now at least, convincing lots of people to buy your whole album remains the most assured route to No. 1.

The further down the chart you go, however, the more progressive things get. On May 16, dance-pop newcomers Walk the Moon landed at No. 14 on the chart with fully 67% the point total for their debut album, Talking Is Hard, coming from downloads of just one song — breakout single “Shut Up and Dance.” On the pure album sales chart that week, launched concurrently with the new Billboard 200, Talking Is Hard was a lowly No. 69.

And this week, Jason Derulo — a singles artist if there ever was one — enjoys a marathon 58th week on the Billboard 200 for his 2013 album Talk Dirty, which came in at No. 127 due to steady streams of hits like “Wiggle” and the album’s title track. Derulo’s similarly hit-filled debut album, 2010’s Jason Derulo, lasted a little more than half as long on the old chart.

“I don’t think it’s a bad thing for the 200 to be more dynamic,” said Josh Deutsch, founder of Downtown Records, whose roster includes Cold War Kids and Santigold. “If you sell 100,000 copies of one track, and stream 300,000 copies of another track, and album sales are negligible, it’s all still revenue.”

The particulars of how Billboard defines the equivalent of an album sale may change in the future. A number of label executives I spoke with said they expected the figure for a Streaming Equivalent Album, 1,500 streams, might come down as streaming services like Spotify and Apple Music achieve greater scale, for instance; or that perhaps Billboard would assign different values for free and paid services, which trigger different levels of royalty payments.

“We’re always looking at how we can make the charts better,” said Caulfield when I relayed those suggestions. “Right now, we think this is the best recipe.”