I interviewed Charles Barron for the first time almost 11 years ago, in November of 2001, for a bare-bones website that was the precursor of the New York Sun, a conservative broadsheet that launched the next year and folded in 2008.

Barron, whose consulting firm occupied a small office on Court Street in Brooklyn, was among the most interesting of a new class of City Council members swept in by term limits, because — with Mayor Rudy Giuliani in his final months — he harked back to a style of racial politics that was, by the late Giuliani years, almost forgotten.

Barron, then 51, had made his name campaigning for “Black English” to be taught in schools (“Ebonics breaks the psychological boundary of White supremacy,” he once wrote), but had won on bread and butter issues: “He is president of the Bradford Street Block Association, and scourge of his neighborhood's drug dealers. He's pressed rap musicians to clean up their lyrics, and he's worked with neighborhood groups to replace schools' coal furnaces,” I reported then. “He’s radical, but he’s effective,” a local official told me.

Though he would don one of several Nehru jackets on formal occasions, he showed up to our interview in a worn sweater.

"I don't have to change who I am, I don't have to placate or capitulate to any white liberal group,” he said, promising to fight for the release of Black Panther “prisoners of war.” He predicted he would win the mayoral election of 2013 with just 10% of the white vote.

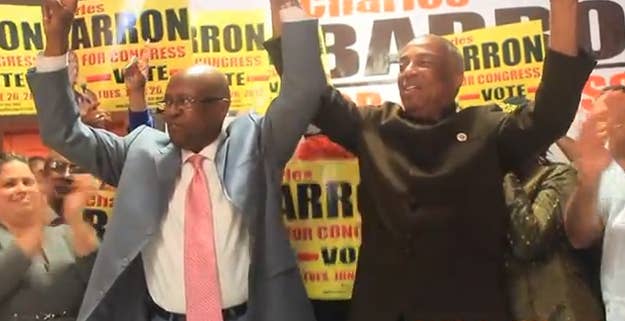

When Barron emerged as a credible candidate for Congress this spring, the notion that he could be more than a gadfly took the city aback. His radical views on foreign policy — he’s praised Robert Mugabe and Muammar Qaddafi, and considers Israel a terrorist state — propelled him into the national news, but the local press couldn’t quite bring itself to take a familiar, personable figure often treated as a harmless throwback seriously as a possible national player. The emergence of a serious visible field organization, and endorsements from the incumbent, Rep. Ed Towns and major local unions, however, forced local and national Democrats to take him seriously, and the Times noted with some surprise last month that he had “regained the ability to shock.”

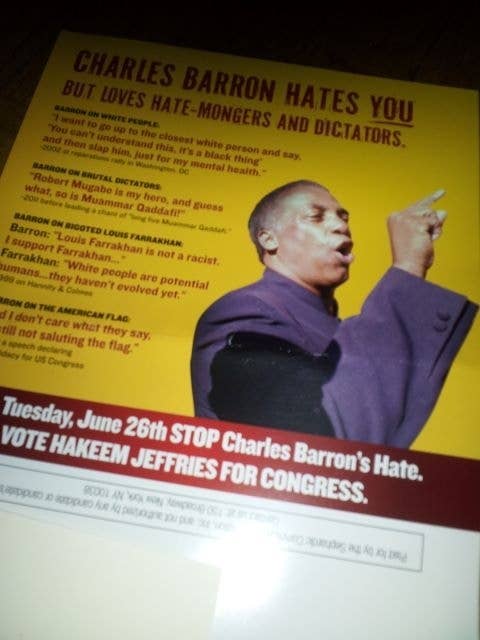

Democrats in Washington, however, viewed his rise with alarm. Establishment donors poured a flood of resources into the campaign of his rival, Assemblyman Hakeem Jeffries, a relative moderate who backs charter schools and raises money hand over fist. Their fear: Barron represents, in caricature, the kind of 1960s racial politics that drove moderates from the party. Indeed, he had already attained occasional moments of national celebrity for a willingness to engage in shouting matches on Fox News, and in 2002 said his frustration with opposition to reparations made him want to “go up to the closest white person and say, 'You can't understand this, it's a black thing,' and then slap him.”

Barron comes in fact from a very specific and narrow ideological stream that flowed out of the political disasters of the 1960s. Barron was, like many young politicos, a radical in the 1960s, a member of the Black Panther Party. But while most of his generation moved to the center, and others went to jail for the party’s acts of violence, Barron simply pressed forward. He founded the National Black United Front in the 1970s, and in 1982 he was arrested with other protesters for trying to “forcibly remove” a white historian from the staff of a research institute focused on black culture.

In the 1980s, Barron moved to Brooklyn to work for an influential Brooklyn minister, Herbert Daughtry. Daughtry is a man of the left and preacher of liberation theology — the philosophy joining Jesus Christ and revolutionary consciousness most recently made famous by the Rev. Jeremiah Wright — who has never been written out of the mainstream of Brooklyn politics, and is a regular presence with Democratic politicians at events protesting police brutality and other causes.

Indeed, Barron’s local politics are of a piece with those of any liberal Brooklyn Democrat. His priorities, campaign manager Viola Plummer told BuzzFeed Monday, are “foreclosures … the increasing rate of poverty …the overarching problem around the issue of racial profiling.” And Daughtry’s circle wasn’t necessarily a ticket to the fringe. His daughter Leah, a minister who has worked closely with him, is a prominent Democrat who was CEO of the 2008 Democratic Convention.

But while other ‘60s radicals moved on, or simply drilled down into local issues, Barron could never quite give up the scope of the 1960s radical vision. He had, in the internal struggles of the black left — between nationalists, black Muslims, and proponents of a more global movement — dived deep into the latter vision, which he describes as “revolutionary Pan-Africanism.” It’s the global black struggle against white oppression that, in his view, aligns him with Mugabe.

Pan-Africanism led Barron to a range of other provocative views. He once told me during an interview in his Brownsville office that one problem with American urban education is that students are required to learn in rectangular rooms. Black students, he said, should be educated in round rooms that evoke traditional African dwellings.

But while Barron’s global views were irrepressible, in a local political scene dominated by mediocrity and petty larceny, he was hard-working, charismatic, apparently honest, and obviously intelligent. He championed his constituents’ bread-and-butter issues, in particular the contract fights of public union workers who are the core of the district. He never missed a protest on behalf of daycare workers who feared layoffs, and his faithful support won him the backing of the main national public sector workers union, AFSCME. That’s why he is a serious contestant today, not a gadfly.

He’s also a serious contestant because, in a low-turnout primary, a small, intense base matters. I first encountered Barron’s core of supporters at a City Hall rally called to defend Mugabe from international criticism of the wave of violence he unleashed after losing the 2008 election. They were a corps of some 20 aging activists, dressed in a mixture of jeans, t-shirts, and traditional African garb and chanting their support for the brutal African leader, whose old campaigns against colonial white landowners had long since turned into new ones against black opposition. Called the December 12 Movement for the date of a 1987 protest against racism in Newburgh, New York, this group has managed, barely, to keep the flame alive, but never quite caught on. An affiliate of the group, the Freedom Party, made Barron its nominee for governor in 2010.

The headquarters for the December 12 Movement and for the Freedom Party is Sistas' Place, a café on Nostrand Avenue in Bedford Stuyvesant that has also become the Barron campaign’s headquarters. Monday, Barron’s aides and volunteers, clad in bright yellow t-shirts, packed the café, bustling around with fliers and hoping to overcome Jeffries’ vast cash advantage ($770,000 to $114,000, much of Barron’s from his own pocket) with their energy. The office was headed by Viola Plummer, a former City Council staffer who lost her job after she suggested the assassination of a black councilman who didn’t support renaming a park after a movement hero, Sonny Carson. Carson is the late radical figure who led a divisive boycott of Korean groceries in 1990 and who, when accused of anti-Semitism, announced that he was in fact “anti-white.” And it wasn’t Plummer’s first brush with controversy: She had been arrested on 1985 on charges of plotting to prison break two members of a gang that killed two police officers in 1981; she was acquitted, though others, including her son, were convicted of possessing weapons including dynamite and machine guns.

Barron may not win today. His shot at the office, though, is a mark in part of his talent and in part of the failure of the mainstream of American urban politics to produce a generation of strong national political figures — a general rule whose leading exception occupies the White House. Brooklyn’s Congressional delegation is undistinguished at best. The aging, defiant Charles Rangel of Harlem remains the state’s dominant black political figure. In the Brooklyn district, the retiring incumbent, Towns, had little profile in Washington or at home. Jeffries, who practiced law at a leading Manhattan firm, is seen by his supporters as an avatar of the “Joshua Generation” of black leaders who, like Obama and Massachusetts Gov. Deval Patrick, can move beyond the civil rights struggles and the tangled urban politics that followed. But voters in the district could be forgiven their skepticism: They saw an earlier generation of young stars like Towns and former Rep. Major Owens rise and then fade gradually.

Jeffries is sensitive to the charge that he isn’t black enough for the district, and to the suggestions from Barron’s allies that support for charter schools means selling out his union constituents to a movement whose most prominent faces are white. He has campaigned on his own effectiveness as a local advocate while working to remind the local Orthodox Jews and white ethnics of Barron’s inflammatory words. An advisor to Jeffries told me recently that the Barron’s worst gaffe wasn’t his embrace of Qaddafi or Mugabe; it was his suggestion that he wouldn’t go to Washington to do his job.

“I don’t know if I’m going to get a single bill passed and I don’t care," he told WNYC’s Brian Lehrer.

Barron’s pitch had been clear: think Pan-African, act locally. Jeffries’ aides, in the final days, have been blanketing the district’s white minority with reminders of the former, but the race will be won or lost in the black majority, where Barron now stands accused of a worse sin: Indifference to the humdrum accomplishments of government.

With Peter Walker Kaplan