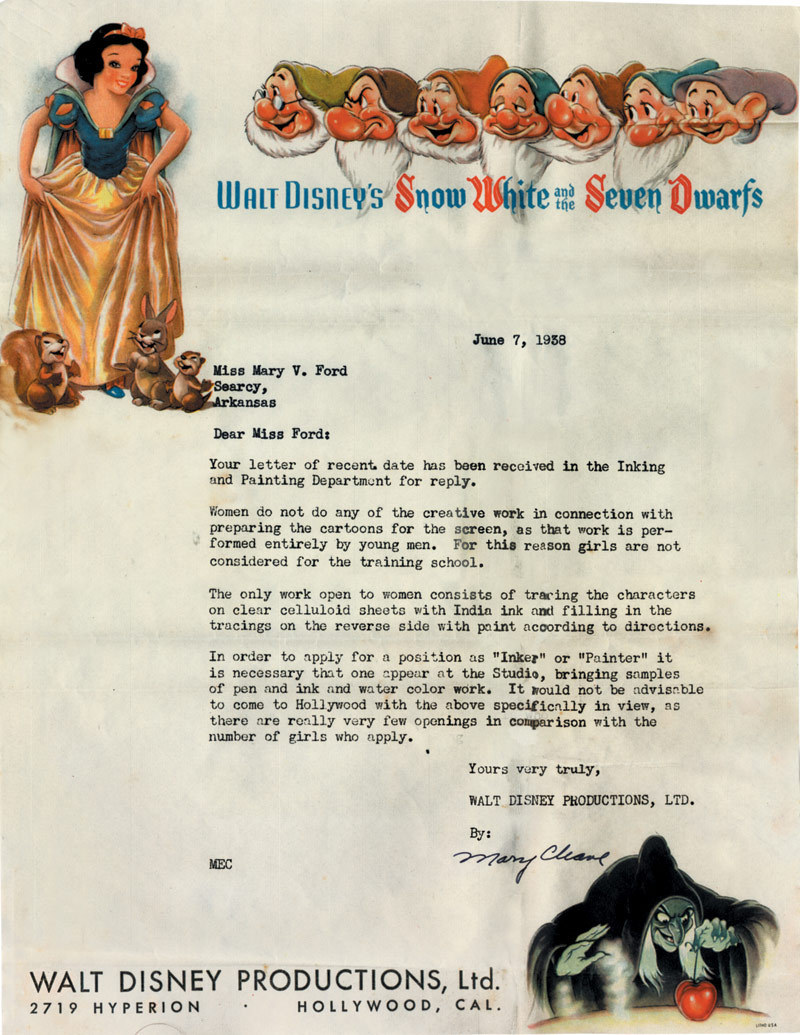

There is an infamous rejection letter that has been circling the internet for the last eight years. “Dear Miss Ford,” the 1938 letter to a would-be animation trainee begins. “Women do not do any of the creative work in connection with preparing the cartoons for the screen, as that work is performed entirely by young men. For this reason girls are not considered for the training school.” The letter advises Miss Mary V. Ford that she can apply to Walt Disney Productions’ ink and paint department if she so desires. Under the original Flickr image of the letter, posted by Ford’s grandson in 2007, a bevy of commenters note that times have changed.

And longtime animator Joanna Romersa agrees. She started as a Disney inker in 1954, and once felt lucky to avoid being fired after she was caught by Walt Disney himself while sneaking into the animation building, where ink and paint “girls” were not allowed. “It was keeping us in our place,” she said. Inkers and painters — those (nearly all women) who would hand-trace drawings from the animators and then hand-paint them on every frame of a film — were not respected as artists; Bill Hanna called them “lettuce pickers.” At Disney, senior staff also had a “Penthouse Club” where women were not allowed, a rule that stood until the 1970s.

Being barred from buildings was far from the worst of it for Romersa, though. “I wanted to progress and was literally told, ‘No, you cannot, because you’re a woman and you’ll get married and you’ll go away,’” the now-79-year-old told BuzzFeed News this spring, beginning to cry. “I just pushed on. I wouldn’t take no.” That perseverance did lead to a directing job — more than three decades later. “I saw many of my male colleagues advance a lot quicker than I did, just because they could bullshit with the boys,” she added.

Women and minorities were shut out from Disney in different and overlapping ways: Animation historian Tom Sito writes in Drawing the Line that the first black man to work as an animation artist at the studio started in 1948 and quietly left two months later; and wearing a pantsuit at Disney was considered a fireable offense for a female employee as late as 1958. But pantsuits are no longer frowned upon, and no one at Disney would send that type of rejection letter to “girls” applying today; times, indeed, have changed.

But exclusion is hardly a thing of the past: Women make up only 21% of working guild members in 2015, and out of the 584 members working as storyboarders, only 103 are women, according to the Animation Guild. One could point approvingly to animation schools as a harbinger of change — last fall, 71% of students in the California Institute of the Arts’ famed character animation program were female, the Los Angeles Times reported. However, that same school year in its Producers Show, which screens the “best” student work, more than two-thirds of the films shown were by male students, in a year when men made up less than one-third of students in the program. Furthermore, women outnumbered men in the program in 2012, 2013, and 2014 — and yet in each of those years, men still outnumbered women in the Producers Show.

While these revelations are in a sense no different from stories women in any industry would tell, the ramifications of their experiences show up on screen, particularly in movies and shows made for children.

Animation professionals interviewed for this article knew the conventional wisdom: “Boys' shows are general audience and girls' shows are niche,” parroted Sabrina Cotugno, a storyboard artist in her twenties, during a Skype interview. Following convention, when Cartoon Network announced its 14 new and returning original series for the 2015–2016 season, only three featured a female protagonist (this includes the two-girls-three-boys ensemble of Teen Titans Go!, despite the fact that Robin is, arguably, the main character), and only one of the network’s shows was created by a woman. It’s a self-perpetuating cycle: Boys see themselves as the heroes, which makes it that much easier to imagine themselves in charge; girls see themselves as the sidekicks, which makes it that much harder.

At CalArts, which has long been something of a Disney feeder school, the students look to the greats for inspiration: in particular, studio films like the first full-length cel-animated feature, Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, released in 1937. But the reverence for the past comes at a cost: “The further you go back in history, the less you're gonna see of gender representation, race representation,” said Cotugno, a former student. In classes, she added, “no one discusses gender.”

Many of these beautiful and technologically innovative films are the product of the so-called golden age of American animation, a period that stretched from the late 1920s through the ’50s. It was during this “golden age” that Mary V. Ford got her rejection letter; and it was later within that age that Romersa had to live with the indignity that her boyfriend could visit her in the ink and paint department while she was not allowed to visit him in the animation building. The “golden age” films are not separate from the politics of the time that produced them: In Snow White, the heroine’s categorical passivity is the source of her virtue; in 1941’s Dumbo, raucous black crows speak in jive; and in 1959’s Sleeping Beauty, the supposed heroine utters 263 words of dialogue — scarcely more than the number of words in these last two paragraphs.

Aside from Disney himself, the driving creative forces at the studio during the so-called golden age were the esteemed Disney animators known as the Nine Old Men. Eight of them began as in-betweeners — the very position Romersa was rejected from on the basis of her gender. There were, of course, no Old Women, because women were discouraged, if not forbidden, from competing for those jobs.

Mindy Johnson, author of the forthcoming book Ink and Paint: The Women of Walt Disney's Animation, said women were in-betweening directly on cels for Bambi, they just weren't getting credit for it. (And they still aren’t: History books — largely written by men — barely mention inkers and painters.) With World War II and an exodus of young men in sight, Disney announced that he would train women for animating positions, to the chagrin of male employees, who, Johnson said, complained that women would drive down salaries.

Despite the undisguised inequity, Disney defenders are quick to point to exceptions, like Retta Scott, the first credited female animator at the studio, a “Disney Legend” who is posthumously hailed in a mini-biography as a pioneer. What the mini-biography elides may be unsurprising: There is no mention that Scott was the first credited female animator for the sole reason that women were discouraged from even applying to the animation department when she started working there in the 1930s. Mary Blair is another Disney Legend exception — a concept artist and designer hired in the 1940s who, her niece told BuzzFeed News, was so unrivaled that she made the only piece of art by a Disney artist that Walt displayed in his home. She was an undeniably outstanding talent, which raises questions about the mediocrity of men who held similar positions.

At the time, men openly justified their discriminatory hiring practices by saying it wasn’t worth training a person who would just leave the job to marry and have children — Romersa was informed by her supervisors in the mid-’50s that this was the reason her advancement was impossible. She did eventually leave her job at Disney to take care of her children, and she worked as an inker from home, where she’d rock her child’s bassinet with her foot while she drew.

The late Disney animator Heidi Guedel wrote in her autobiography that Wolfgang Reitherman, an Old Man, was “quite outspoken” in his attempt to avoid working with female animators. She began working at Disney in the 1970s, and also described an office where a male colleague had covered the walls in nude photos of women. Worse, a respected assistant animator who had worked at the studio for decades would give her back rubs and grope her breasts in the office, she wrote, describing it as an “awkward and embarrassing experience” that she was too intimidated to confront him about.

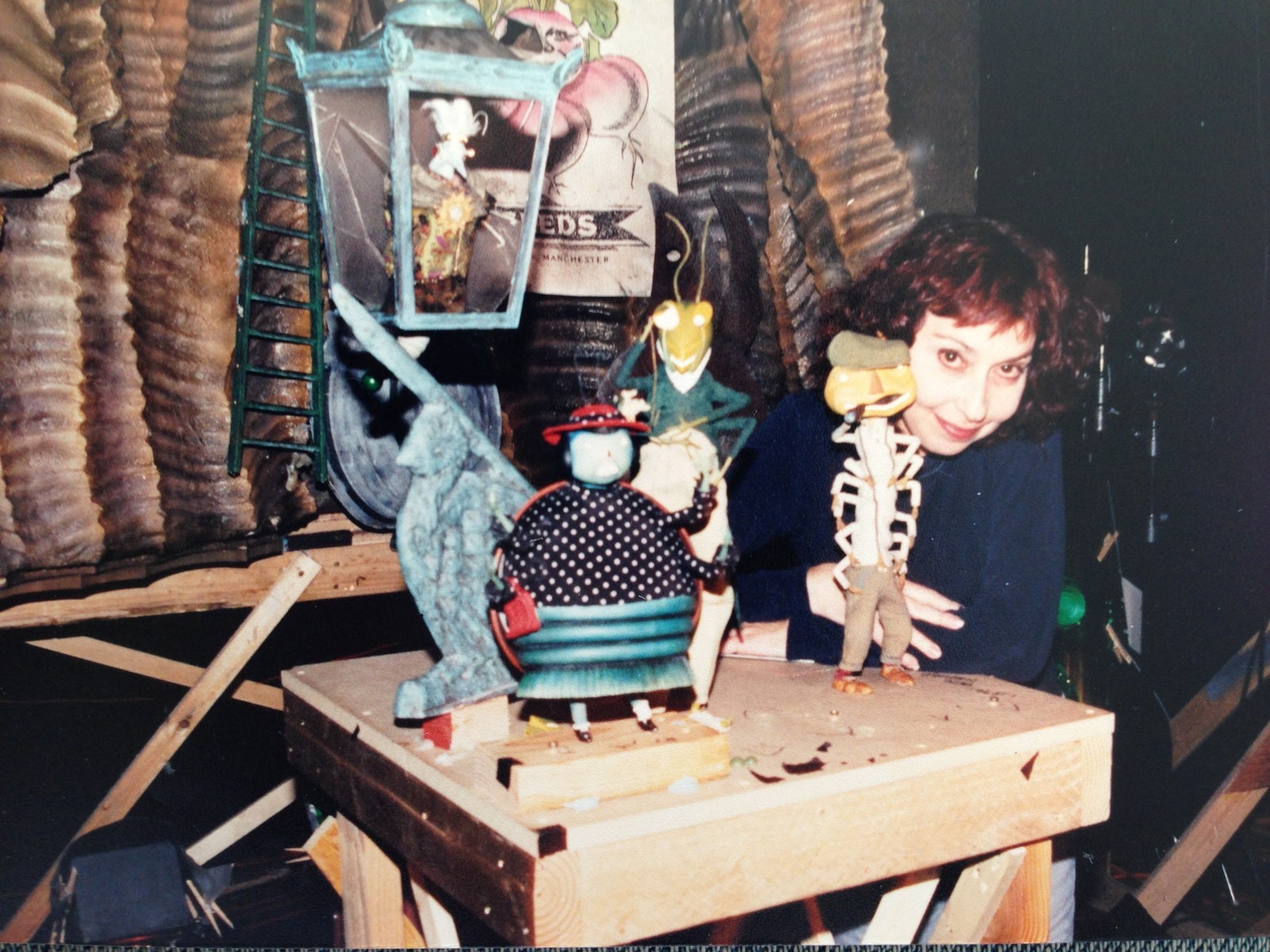

Romersa reported similar interactions at Hanna-Barbera: She said her career really took off after she was promoted to head of the assistant animation department there, explaining that a female colleague advocated for her to get the position after the studio fired a man whose sexual harassment of a woman who worked there had escalated to stalking. And when Romersa was working at the studio of animation pioneer Ralph Bakshi as a secretary and production manager in the ’70s, she “used to think Ralph was mad at me if he didn’t pat my butt or pinch my boob. … Bakshi was a bastard.” In 2013, Bakshi, who did not respond to BuzzFeed News’ request for a comment, was described by Entertainment Weekly as a “maverick cartoonist and filmmaker.”

A second artist who worked at Bakshi’s studio in the ’70s and ’80s did not remember him physically touching his female employees, but did say he frequently made remarks to her “that would be considered sexual harassment now.” The former employee, who asked to remain anonymous, said Bakshi would offer to have sex with her in his office, and when she would decline, he would laugh it off as if it were a joke. “It made you wonder who actually did take him up,” she said, adding that whenever a woman got a promotion or a desirable credit on a project, other artists would assume that woman had performed sexual favors for Bakshi. She left the studio, and did some freelance work for him in the late ’80s. The last time she saw him, the same treatment she endured while working at the studio continued, in the presence of her toddler. Still, she said she was grateful for the opportunity: Bakshi was one of the few studio heads who would hire women at all.

Though they came up through the ranks at a time with less open hostility to women, animators Sari Gennis and Bronwen Barry, who met more than 20 years ago working on FernGully: The Last Rainforest, disagreed on whether things had actually gotten better or worse for women in the workplace; it’s a clash that hinges on whether they prefer their discrimination subtle or straight-up. Gennis, who works primarily in visual effects — an even more technical, male-dominated field than regular animation — was frustrated with the subtlety. After Barry said many men appear resentful when they lose a job to a woman, she asked her friend if she agreed. “No,” Gennis answered. “Because I never see that happen.”

At a recent job, Gennis said, she was the first person to be laid off, despite being the only trained animator on her team. Her supervisor “said he wanted to keep his ‘guys’ working,” she said, using air quotes. “If a guy had my résumé,” Gennis noted, gesturing to the extensive two-page document she was carrying around in her bag to drive the point home, “they would be bowing down in his path.”

Barry, conversely, is a storyboard revisionist on a Disney XD show called The 7D, which has a near equal gender ratio behind the scenes. She said both that she didn’t feel her gender had affected her career much, and also that she believes not having children has made her “perceived availability and efficiency” much more favorable; she has heard women with children referred to as “high-drag.”

But Barry did say gender discrimination emerged in the form of indifference to her ambition when she was starting out — as an assistant animator, she felt she wasn’t encouraged to pursue animation or storyboarding. Gennis, too, felt like she wasn’t encouraged as a young person in the same way men were. She attended CalArts in the mid-’70s, when there were very few women in its animation programs. One year, she and another woman were the only two students who didn’t go on a school trip to Disney’s animation studios: Instead, they were taken to observe a makeup artist. “They said [the trip] was ‘full,’” Gennis said — but it was hard for her to imagine CalArts sending two men to observe a makeup artist. “It’s always bothered me.”

Gennis said the school’s administrators told her to get a job in ink and paint to get her career started, but she did not want to be pigeonholed. (CalArts did not respond to BuzzFeed News’ request for a comment.) Instead, she got a job at Robert Abel and Associates, where she worked her way up to commercial director. Around 1980, despite the promotion, she was still “getting the jobs no one else wanted.” She recalled asking the creative director when she would get to work on the high-end commercials; he answered, “When you grow a penis.”

In a way, Gennis appreciated his honesty; no one would say that in so many words to her today, although she feels it’s sometimes the truth. “It’s all still there, but it’s all gone underground,” she said. Still, Gennis recently posted something on Facebook about the very small number of women working as technical directors and artists in visual effects. A male Facebook friend who works in VFX “actually posted that it was because VFX had gotten so technical,” Gennis said with disgust.

Like Gennis and Barry, animator and designer Carole Holliday came up through the ranks at a time when there were very few women animators to look up to (and virtually no female directors in animation). “I wanted to be a director — wanted to be and want to be,” said Holliday. Most recently a storybook artist on Disney Junior’s Sofia the First, she spent years struggling to assert herself professionally. At one point, a female colleague in development asked her about her career goals, and Holliday gave a response in upspeak: “I think I want to direct?” As she explained it, “I could never get to the point of saying, ‘This is what I want,’ because it felt like I was being demanding.” Instead, she had to learn how to say what she wanted “without being strident, because I think sometimes I can be shrill.”

Holliday told a similar story about the beginning of her career, when she assisted Glen Keane: The veteran Disney character animator advised her on her portfolio when she applied for a job at the studio. After she was hired, she recalled slinking into his office once and standing in the corner. “He was like, ‘You need to go out, and you need to come back here and act like you belong here,’” she remembered. She did, and later, when Keane gave her a close-up of Ariel to in-between on The Little Mermaid, he demanded that she accept the task with confidence. (Of course, not everyone was so encouraging, but after recounting a more negative story, Holliday asked BuzzFeed News not to publish those details. She wrote after the interview that she is not “the type of person who is disloyal or contentious and prone to hold grudges.”)

But Holliday tends not to see issues in her career as gender- or race-related, although she’s both female and black in an industry that doesn’t have many of either group, let alone both (the Guild doesn’t keep records of its members’ races, but Holliday referred jokingly to another woman as “the other black animator”). “I see it as more personality stuff than ‘male’ or ‘female,’” she said. “Which is probably why I have a different perspective than a lot of people. They’ll see it as misogyny, I just see it as, OK, we just didn’t click.” She told a story about working on the 1999 Disney animated film Tarzan where she explained to her male colleagues that Jane, a bourgeois woman with Victorian sensibilities, would be very uncomfortable in a scene where a nearly nude Tarzan is pressed up against her. They dismissed her note. However, she was happy to say that later, without her input, Keane made Jane look uncomfortable in his boards — he could think from a woman’s perspective, Holliday said.

She was unfazed, too, by the revelation that CalArts featured so much more male work than female work in its largely faculty-curated Producers Show, despite having a majority of female students. “I think people can blame gender or race [for] a lot of things. Sometimes it’s just, you’re not good,” she offered by way of explanation. It’s the same logic that allows people to point to Mary Blair as proof of meritocracy — a logic that celebrates the women who outshine men by such a wide margin that they cannot be ignored and fails to account for those left behind.

One woman who could not be ignored was the redhead in the outlandishly ruffled dress who climbed onto the stage of the Dolby Theatre in winter 2013 and accepted her Oscar for Brave, a movie about a mother and daughter who go on an adventure in the forest, fight off a giant bear, and break an ancient curse. That woman, Brenda Chapman, was the first woman to win an Academy Award for Best Animated Feature Film, and she was also the first woman director at Pixar; Brave was Pixar’s 13th film and, not coincidentally, its first to feature a female lead. Chapman was the only creative member of the studio’s “Braintrust,” a feedback committee whose most cherished value, according to Pixar’s president, is “candor.” She is an established animator with a long career: She started on The Little Mermaid and was a story artist on Beauty and the Beast. She wrote and boarded the scene where the Beast yells at Belle while she’s dressing his wounds — and made sure that Belle yelled back. For The Lion King, she was promoted to head of story.

Chapman wasn’t particularly aware of any bias against women while she was at Disney, despite being wildly outnumbered by men. She did, however, recount that the man who hired her told her she “only” got the job because she was a woman. “It really took the wind outta my sails, I have to say. Because I wanted to be hired for my talent, not for my gender,” Chapman said. “I felt like maybe I didn't — maybe there were other people who deserve the job more than I do, but I got hired because I was a woman, so it made me feel like I had to work harder to prove that I deserved to be there.”

It was something her exclusively male colleagues — who certainly were hired in large part for their gender — were never forced to reckon with. Still, they made her feel welcome, and she thought her presence in the room made them more sensitive in the way they talked about female characters. In the original sequence in The Little Mermaid where the prince guesses the mute princess’s name, Prince Eric was supposed to name the ambulatory mermaid himself, like “a new pet,” Chapman said. To her delight, a male artist noted that the scene was disquieting.

After Disney, Chapman moved to DreamWorks Animation and directed the 1998 film The Prince of Egypt before heading to Pixar in 2003. Braintrust member Joe Ranft, she said, initially hired her to fix the girl characters in Cars — there were no women in Pixar’s story department when she started there in 2003, and those flimsy female cars (who “were all kind of secondary to their male counterparts,” Chapman said) were too far along for her to help. But soon after, she began developing what would become Brave.

Once filmmaking was underway, Chapman made sure her female artists weren’t talked over in storyboard meetings. Emma Coats, then a young Pixar newcomer, said the director “would quiet the room and be like, 'Emma, you started to say something.'” It helped Coats realize that her ideas were worthwhile. Chapman did the same thing for male artists who were quiet, Coats said.

Then in fall 2010, Chapman was unceremoniously fired from her project. The exact circumstances of her dismissal are shrouded in nondisclosure agreements — Chapman herself cites “creative differences,” vaguely singling out a disagreement between herself and Pixar’s Chief Creative Officer John Lasseter over the central character, Merida, as especially divisive.

“To me, she could’ve behaved exactly the way any of the male directors behaved, but it would have been taken differently,” Coats said, declining to elaborate further. “Which is frustrating. Realizing that, it made me realize, There’s nobody. Without Brenda to look up to…there’s nobody I can look up to. … Imitating the guys isn’t gonna give me the same results as it gives them.” Coats left Pixar — and animation for the most part — mainly because of what happened to Chapman. “When she was removed from her project, I felt kind of lost,” she said. Because there were no other women directors to look up to, Coats couldn’t tell if the way Chapman was treated was an anomaly or part of a pattern (although hiring exclusively male directors is itself a pattern). “I can’t see why what happened to her wouldn’t happen to me,” Coats said. (A representative for Pixar, which is owned by Disney, declined to comment on this story and declined to answer questions about how many women work in creative positions at the studio now.)

It was striking for Chapman, too. “I think my Brave experience was my first foray into, Oh, no, it is different for us girls out there.”

And that difference shows up on our screens. A 2012 study from the Geena Davis Institute conducted by Stacy Smith, Ph.D., at the University of Southern California's Annenberg School for Communication and Journalism found that female characters made up 31% of speaking characters in primetime children’s shows — less than a third. Only 19% of children’s TV shows had an approximately equal number of male and female characters.

Pixar, America’s most celebrated animation studio, produced 12 films starring male characters before Brave premiered in 2012. Chapman said that while she was making her movie, a Disney employee told the executive team at Pixar, “We don't know how to market a movie about two arguing women.” Just this year, a project she was developing for DreamWorks Animation with two female main characters and two male secondary leads was described by an executive as “too female,” according to Chapman, even in the wake of the wildly successful, girl-driven Frozen. “There are just as many women as there are men!” she said. (A DreamWorks representative declined to comment.)

And this mentality is drilled into women studying animation. In a class at CalArts, Cotugno recalled, an instructor lectured on the difference between “feminine” and “masculine” story elements — “which is a little hard to describe, mostly because it’s fucking bullshit,” she said. Elements such as linear storytelling and big external stakes were “for men,” while relationships and emotional storylines were “for women.”

The strained understanding of female characters was thrust into the public eye in 2013, when the head of animation on Frozen claimed the faces of female characters were “really, really difficult” to animate. This statement compelled Nancy Beiman, a longtime animator who is now a professor at Sheridan College, to include a section in a new edition of her animation textbook debunking the notion that there is something inherently masculine about certain movements: “There are any number of women who can walk with direction, with a sense of purpose,” she said in a phone interview. Her book Animated Performance declares that there “are no body attitudes or emotions that are unique to one sex.”

According to Cotugno, CalArts subtly encourages men in story and women in design. Her classes were generally gender-balanced, yet it was “primarily guys who would get known for being great storytellers,” she said over Skype. Female students would be rewarded for color or graphic choices, which Cotugno termed “the pretty part.” “Many women would start out thinking they wanted to storyboard and decide against it, saying, ‘I can't really articulate why but I just don't feel good about it.’” It happened to Cotugno: She abandoned storyboarding after feeling alienated by the aggressively masculine behavior she encountered. In an email, Cotugno said the actual incidents were subtle. “It would be so easy for guys to say, ‘You’re exaggerating,’ or ‘You’re overreacting, that was nothing,’” she explained. It was only after college that Cotugno fell back into storyboarding professionally — and realized that it wasn’t storyboarding she didn’t like, it was story bros. Even now, working on a show with people she likes and, she noted, a male showrunner who took a chance on her despite her inexperience, it sometimes gets uncomfortable to be outnumbered. “I’m always the one like, Oh, here’s the queer feminist, gotta say her social issues again.”

Getting more women to pursue story — and to stick with it — is essential to getting more female characters on screen. Anastasia,* a twentysomething female story artist, said she often finds herself gravitating toward female characters on a project, both because she relates to them and because she worries her male colleagues will not do them justice. She recently worked on a film where female characters had “a very hard time being formed or talked about,” she said. “It’s troubling to me, because female characters are just people.”

Coats said that at Pixar “a lot of times, the guys on the story team, or guys who would give feedback, would talk about female characters in terms of [their] wives or daughters” — specifically, she said, Merida, the main character of Brave. Although that was not a universal pattern of thinking, she never encountered a woman who thought about male characters only in terms of male family members. “You can’t afford to think of male [lead] characters in terms of husbands or brothers,” she said.

The most disheartening thing to Anastasia is that there’s a perception among her co-workers that animation is a pure meritocracy, when in fact networking plays a huge role in getting jobs. “My biggest fear is that I won’t be seen as a team player just because of my gender,” she said — her male colleagues assume she’s offended by “even poop jokes,” an absurd but real roadblock to her directorial ambitions.

Ziah Fogel, who specialized in crowds animation at Pixar, said the studio is “very clique-y in general.” She described herself as “a bit aggressive for a female” and said she fit in with her mostly male co-workers because of that. She felt she got preferential treatment because of her ability to fit in to “the drinking culture” and hold forth on whiskey. Other women, she said, could be put off by the “culture of bros.” And if you are put off by it, you might not advance, or you might give up on narrative animation like Coats did.

After Beiman graduated from CalArts in 1979 — as one of the first female students in the animation program — she went to work in Germany, where “there was no old boys’ network because there were no old boys,” she said. She was promoted to director there, something that is still out of reach for the majority of stateside female animators today. Beiman began teaching animation in 2000, and she said things have gotten better for women since then. “I used to have to tell the girls, ‘Find someone who isn’t afraid of you.’” It’s something she doesn’t feel the need to do anymore.

But women are still concerned about airing their grievances, despite the fact that, again and again, women interviewed for this story said the men they worked with would be appalled to learn that women felt shut out, and that the exclusion was “a matter of ignorance,” as Anastasia put it. “They’re really good people, and they would be horrified to learn that they’re excluding people,” said a production manager who worked at Pixar and who, along with Anastasia, initially wanted her name on the record and later asked to be anonymous. The production manager made it clear that she loved Pixar and was worried that her words would be perceived as derogatory, although the most divisive thing she said was that she had worried about losing female artists from the studio and proactively sought to mentor them. Several other women in animation noted that it’s a small industry and they didn’t want to be seen as troublemakers — as Chapman put it, “There are those of us who are free to speak a little more abrasively about how things are going.”

But there are many who are not.

* This name has been changed at the request of the interview subject.

Update

This article has been updated to clarify that the Geena Davis Institute study was conducted by Stacy Smith, Ph.D., at USC's Annenberg School for Communication and Journalism.