Anne Miller lives in Jordan, Montana, three hours from the nearest mall, in a cabin she and her husband built themselves. If you search her address on Google Maps, you have to zoom out eight times before the nearest city comes into view. She’s an executive for an agricultural organization; in her spare time, she’s a competitive precision rifle shooter. She periodically blogs for agriculture.com. Her Facebook page is a kaleidoscope of Montana sunsets, warnings about road conditions, and pictures of her little girls playing against the backdrop of big sky. In many ways, she’s the last person you’d think would be the target of a Silicon Valley startup.

Anne leads what she calls a “fashion double life”: Working from home in Jordan, she’s usually in jeans and a T-shirt. But as soon as she hits the road for her communications job, she’s in businesswear. It’s a role that calls for her to zigzag between two states regularly: 10 hours to Cheyenne, Wyoming; five days later another nine to Hamilton, Montana. For these trips, she wears a conservative uniform of suits, blazers, and practical heels. “I have a closet full of Calvin Klein dresses,” she told me, “but no one in Jordan has ever seen me in them.”

To get clothes for either half of her fashion double life, Anne has limited choices. Drive 90 minutes northwest to Miles City, and there’s a Maurices, a Walmart, and Stylez of Miles, which trades in heavily bedazzled Western wear; drive three hours south to Billings, and there’s a classic mid-level mall: Zumiez, Dress Barn, Dillard’s. She could order clothes online, but returns are more hassle than they’re worth. Her closet began to feel stagnant, but she couldn’t muster the effort, or time, or energy, to rectify it.

Anne’s experience is not unique. For many, everything that had once felt fun, worthwhile, or satisfying about the shopping experience has gradually disappeared. And although we’ll keep buying clothes, the strength of a given industry hinges on the ability to feel good about shelling out hard-earned money for commodities — so good, if possible, that we forget the transactional aspect altogether. As everyday tasks like using a phone, doing laundry, or calling a cab are being made simple, graceful, and even enjoyable, strolling under fluorescent lights trying to find a specific size in an unsorted sale rack feels hopelessly broken.

It’s broken in rural areas and midsize towns, where it takes place at J.C. Penneys and Walmarts and dying malls colloquially referred to as “All this crap and still no Gap.” It’s broken at T.J.Maxx, Forever 21, and Old Navy, where the unifying aesthetic is that of a bomb going off in a pile of clothing. It’s even broken online, where endless scrolls of clothes are piled into virtual carts, knowing you’ll return at least three-fourths of what you receive. And while some find tremendous pleasure in the hunt for a bargain, that sort of hunting takes time — a luxury many women, no matter how wealthy, lack.

The simplicity, satisfaction, and convenience of the on-demand economy is precisely what so-called “fashion tech” is trying to replicate in retail — and for people like Anne. For the last 10 months, Anne has been using the algorithm-enabled styling service Stitch Fix. Stitch Fix uses a combination of data science and personal stylists to select a “Fix” of five items sent directly to your front door. If a customer keeps one item, the $20 styling fee is applied toward its purchase. If she keeps everything, she receives 25% off the total cost of the box. Items are priced between $28 for a pair of earrings and $188 for a pair of jeans, sourced from lesser-known brands (Kut from the Kloth denim) and proprietary ones (six in total). Stitch Fix doesn’t release statistics about its number of customers, but the company projects more than $200 million in revenue in 2015.

Instead of searching aimlessly for someone to unlock the fitting room, then, the ego boost of expert, concentrated attention. Instead of a cheap plastic yellow bag thrown in the backseat, a package, filled with wonder unknown, arriving at your doorstep like a quotidian Christmas. “Getting my Stitch Fix is pretty much the highlight of my month,” said one customer, a mother of three from Ohio. “Is that sad?”

The success of these companies isn’t a tale of “disruption” so much as one of reversion. Software and technology won’t “eat retail,” as venture capitalist Marc Andreessen proclaimed in 2013. Brick-and-mortar stores will decrease in number but not disappear; Star Trek uniforms fitted by body scanners aren’t the imminent norm. But the expanding consumer cults around these services underline an eagerness to embrace a different, if not entirely novel, way to shop.

Ostensibly, of course, these women are shopping for clothes. An exquisite, restful, delightful experience of acquiring a wardrobe. But Stitch Fix — and competitors like Le Tote, Tog + Porter, Gwynnie Bee, Golden Tote, and the male-oriented Trunk Club — also offer the product of taste, and its elusive twin, confidence. As Christine Hunsicker, CEO of Gwynnie Bee, put it, “What these women are buying is that moment when you walk into work and your co-workers say, ‘That’s amazing.’ That delight is very addicting and very powerful.”

At their best, these services unlock the mystique of fashion for the masses, democratizing the “good taste” that was ostensibly available to a privileged few. But for all their innovation, what if the glamour of a personal stylist and the celebration of data science merely distract from, rather than actually fix, the problems of women’s fashion?

Shopping didn’t always feel this way. You can trace its decline through the history of Lewiston, a small town located at the confluence of the Snake and Clearwater rivers in Idaho’s panhandle. It’s been a boomtown, a timber town, and an ag town. It’s also where Anne and I grew up. Today, the population hovers around 30,000, but that number belies the central cultural role Lewiston has played in the area for the last century. For 60-plus miles in every direction, “going to town” means “going to Lewiston.”

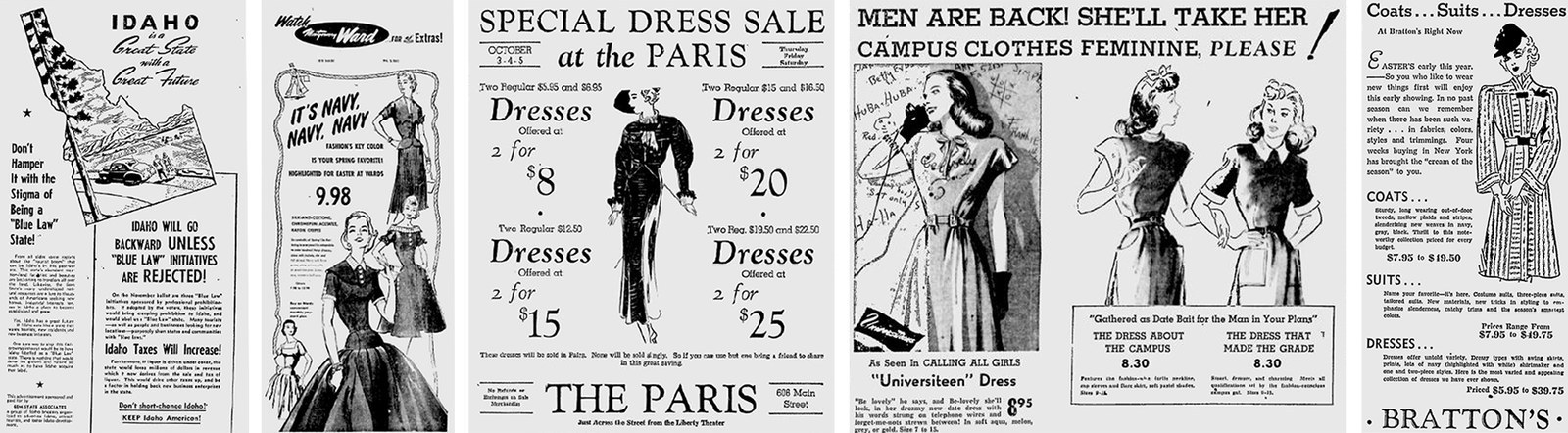

When Anne’s great-grandmother went shopping in town in the 1920s, her experience was typical of thousands of midsize towns across America. Downtown Lewiston was dotted with so-called “specialty shops,” some of which catered specifically to men (Buster Brown Shoe Company) or women (the Vogue Hat Shop). The emphasis was on impeccable service: The salesperson could be expected to remember your measurements, recent purchases, and general tastes — very much akin to the role of a stylist today.

Other shopping took place at department stores: Any town with more than 1,000 people had several, including one that catered to upmarket, middle-class men and women of means. In Lewiston, that store was CJ Breier’s, housed in a grand, five-story, “Chicago-style” building. As retail historian Jan Whitaker explains, these stores “had the authority to say what was ‘correct,’” with the assurance that “what they bought was not in bad taste or beneath their station in life.”

At specialty shops and department stores alike, the emphasis was always on quality. The mantra that “it’s always better to buy one right thing than 10 cheap things” was passed down through Anne’s family and mirrored the American attitude toward clothing for the bulk of the 20th century. Anne’s great-grandmother, grandmother, and mother all wore most of their clothes on a weekly basis and wore them out. The reliance on quality and customer care, however, was about to be compromised — not just in Lewiston, but also across the nation. In 1965, local ads trumpeted the arrival of the Lewiston Center Mall on the then-outskirts of town, featuring a Montgomery Ward, a W.T. Grant (think Kmart), a Tempo “Variety” Store, and a grocery mart.

Like so many other mall developments, Lewiston’s siphoned business from the once-robust downtown; by the end of the ‘70s, all of the remaining downtown department stores had relocated to the mall. My mother remembers it during the '80s as “racks of horrible clearance,” mostly rejects from the Seattle branches; “plus, having a grocery store in it made it feel so lame.”

The state of the Lewiston mall — and retail outlets across the country — reflected price pressure from “discount department stores” (Tempo’s; T.J.Maxx), outlet malls, and, later, Walmart and Target. To compete, department stores instituted cascading series of sales, so regular as to inculcate consumers with the idea that every item would eventually go on sale if they just waited long enough. Like anyone who grew up in Lewiston, Anne can still sing the jingle, set to the tune of Harry Belafonte’s “Day-O,” for the one-day sales at The Bon Marche so frequent as to seem like a weekly event. In this way, “full price” became tantamount to “overpriced.” By 2005, in Lewiston and across the country, more than 60% of department store purchases were made on sale.

There were certain items for which Anne’s family was still willing to pay full price — they just weren’t in Lewiston. They were a two-hour drive away in Spokane, Washington, where the Nordstrom still clung to its original department store dignity, offering only semiyearly sales and a more traditional shopping experience. “I remember sinking deep in the couches in the Nordstrom fitting rooms,” she recalls, “waiting what seemed like hours for my mom and grandmother to finish shopping.” Their go-to item — for themselves and, later, for Anne — were Foxcroft blouses, which were relatively expensive (around $70 in the 1990s) but of impeccable quality.

With their willingness to pay full price for quality, Anne’s family was in many ways exceptional. At the beginning of the ‘90s, shoppers began embracing “specialty” stores like Gap, The Limited, Ann Taylor, and J.Crew. None of those stores were available in a town of Lewiston’s size, but I remember ordering back-to-school clothes from the J.Crew catalog over the phone, slowly repeating the item number for the customer service agent on the other end of the line.

Like so many others of my generation, I was growing up with no concept of quality. As Teri Agins writes in The End of Fashion, Gen X and younger is “largely ignorant of the hallmarks of fine tailoring and fit. Jeans, t-shirts, stretch fabrics, and clothes sized small, medium, large and extra-large are what this blow-dry, wash-and-wear generation have worn virtually all their lives.” Who cares about quality when you could have the assurance of a brand name? Buy a “classic” item from any one of these stores, the understanding went, and always be in fashion.

For years, department stores like The Bon Marche had fended off the price competition by offering a holistically better shopping experience. But that strategy could only last so long. The Bon increasingly came to resemble every other store in the mall: less variety, more brand-conscious, and endlessly refilling with slightly new variations of established styles.

Today, the Lewiston mall feels like a ghost town, and the downtown remains a gutted shadow of its former self. If you’re plus-size or petite, the fashion situation is even more dire. Elsewhere, Forever 21, H&M, and Zara, the polyblend behemoths of “fast fashion,” provide quick salvos, taking the trends of the existing retail structure — a lightning-fast production speed, the expectations of bargain prices, the deprioritization of the shopping experience — and making them their hallmarks.

When it comes to these clothes, fashion historian Elizabeth L. Cline explains, “Quality has a relative meaning. It is best measured in washes. As in, how many times can you wash it before the fabric pills or stains, the garment loses its shape, a button falls off, or a seam bursts open?” These low expectations extend to the entire shopping experience, from the frenzied fitting rooms to unforgiving return policies. In this way, the understaffed, overstuffed experience we now associate with so much shopping has become the new normal.

Today, retailers are struggling to remain both relevant and profitable. Online, J.Crew, Anthropologie, and Ann Taylor are expanding their “exclusive” offerings and “athleisure” collections; offline, others are closing brick-and-mortars (Bebe, Abercrombie, Aeropostale) or shuttering altogether (Wet Seal, Delia’s, Deb). Yet they’re refining and tinkering with a paradigm that still aggravates most and pleases few. Just because an object is cheaper doesn’t mean that people actually delight in the process of purchasing it.

Anne first heard about Stitch Fix from Katie Pinke, whose blog, The Pinke Post, offers “a prairie perspective from the heart of rural North Dakota.” Pinke’s Stitch Fix testimonial is similar to hundreds of others that dot the mommy blogosphere, complete with pictures of various items, a disclaimer that Stitch Fix did not pay her to write the review, and a rationalization for the cost: "A woman who looks and feels good can be a happy woman," Pinke says. "A happy mama makes a happy family. Whatever it takes, I’m justifying Stitch Fix in my life."

Word of mouth is Stitch Fix’s primary form of advertising. Google “Stitch Fix review” and find yourself caught in the undertow of hundreds of reviews, each of which invites readers to try out their own Fix — which, upon completion, kicks back a $20 credit to the original poster, like a digital Avon scheme. A single review from a blogger with a medium-size audience can generate dozens of referrals — and enough credit to cover months of future Fixes. It’s a hugely effective, if somewhat sly, means of incentivizing customers to share their experiences with the service.

When Anne signed up last fall, she was asked a mix of questions about her life (“Are you a mom? Are you curvy on your bottom half? What areas do you like to flaunt or hide?”), her typical sizes, her height, weight, and age, and her preferred price ranges before designating a rating for six collections of clothing. She was then prompted to link to her Pinterest board and leave a brief note for her stylist. “In work, I’m a Talbots and Pendleton kind of gal,” she wrote, adding, “I love cowl, drape, and ballet necklines,” and, “My husband loves me in jeans and a t-shirt.”

After eight boxes, she’s purchased 11 items, including an $88 pair of jeans, a $64 dress, and a $74 blazer. With each Fix, the algorithm — and the stylist that guides it — theoretically gets smarter, zeroing in on Anne’s true, if unstated, size and style profile. The algorithm works in part because she provides regular, detailed feedback — but also because she has a “straight”-size (0–14) body that it’s capable of fitting. “By this point, they probably have me as the Puritan Chic Who Hates Funky Back Pockets and Low Fronts,” she joked.

She’s probably not far off — even if the algorithm wouldn’t phrase it that way. The man responsible for that algorithm is Eric Colson, who joined Stitch Fix as chief algorithms officer after nearly six years building Netflix’s renowned recommendation system.

Colson has a welcoming, soft-cornered face; he’s lived in and around San Francisco all his life, and he has the look, tan, and build of a man who loves his road bike. I met him at the Stitch Fix headquarters in downtown San Francisco, where vintage sewing machines and dress forms serve as conversation pieces against the backdrop of a typical tech startup.

Colson’s traditional startup pedigree has served Stitch Fix well, especially as they’ve pitched the 94% male world of venture capital. He initially balked at the opportunity to serve as an adviser, but was swayed into a short-term commitment by Stitch Fix’s CEO, Katrina Lake. What started as 90 minutes of consultation quickly ballooned to 20 hours a month. “I was just obsessed,” Colson explained, with a sort of residual wonder. “I was on vacation and I found myself up at three in the morning just dabbling with the data.”

At Netflix, Colson and his team only had a limited pool of user data from which to draw: a zip code and the user’s history of previously rated titles. They didn’t even know a user’s gender. By contrast, Stitch Fix users were shoveling personal data toward the company in bulk, providing detailed information not only about themselves, but the items they purchased and returned. The relationship between Stitch Fix and its users was “more copacetic, more natural,” Colson explained. “A customer will say, ‘I think they missed on this shirt. I better work to tell them better.’” The data that “stuck” to an individual blouse (too big, too sheer, no one in Minnesota likes it) was incredibly rich, even in the early days, when Colson was working with a fraction of today’s user base.

But what really hooked Colson was the promise of an analog “guide” who could interpret the algorithm’s data. Observe, in other words, what an algorithm simply could not see.

When Anne’s stylist sits down at her home computer, she logs in to a dashboard filled with Fixes. When she clicks on Anne’s profile, her “closet” auto-populates based on previous purchases and style preferences. In her original style profile, Anne marked that she doesn’t want anything with animal prints; nothing cheetah-printed will appear on the stylist’s dashboard. “I always picture it as that scene in The Matrix,” Colson told me. “You walk into the Stitch Fix ‘store’ and it’s humongous and vast, but then a snap and a whoosh and only the things that are relevant come down.”

Consulting Anne’s notes — “I need some skinny jeans and a dress for work” — the stylist then selects from the available items. As the algorithm accumulates more information about women’s fashion preferences, Stitch Fix has used that data to launch its own “in-house” clothing lines, which focus on what CEO Katrina Lake terms “needs in the marketplace that were hard to consistently fill.”

“Everyone needs a work cardigan,” Lake explained. “Our vendors would sometimes show one, sometimes not, sometimes it’d be too on trend. It was super unreliable.” Those items are now in-house brand specialities, and in many ways, they’re indistinguishable from the rest of the clothing that fills Fixes. With names like 41Hawthorn, Market & Spruce, and Brixton Ivy, these labels are meant to blend in with the other mid-priced, blandly evocative brand names.

Stitch Fix’s stock is purposefully behind the fashion curve. "Other brands take a big risk and guess what people are going to be into two seasons from now, knowing that some will fail," Colson told me. "I don’t feel we’re doing that trendsetting.” Instead, they’re figuring out what’s already working, and then using their in-house brands to fill those needs. In some ways, it’s a profoundly conservative approach to retailing. Or just a savvy one. Most Stitch Fix users — Anne in rural Montana or a fortysomething mom in suburban Arizona — don’t want to be setting trends.

Working with customer purchase data, Stitch Fix judges fashions according to grades — A, B, or C — and buys accordingly. An "A" style is assured satisfaction: a camisole, a tried-and-true cut of jeans, a pair of leggings. The demand is static, the risk is low; Stitch Fix thus buys “deeper,” the industry term for “more.” “B” is for a bit less assured: a blouse cut in the current fashion, or a pair of mint-green skinny jeans. And “C” is for “risky”: this year’s jogger jeans, say, or an orange draped cardigan. It’s not that C items are all fashion forward so much as less likely to fit everyone’s taste. Ideally, a Stitch Fix stylist will figure out how to make the customer feel satisfied and socially acceptable with her A and B picks, and unique and personally “understood” with her C picks.

Stitch Fix is by no means to the first to embrace this buying model. What differentiates it, then, is the precision with which it not only tracks and physically accommodates the far reaches of the model, but also anticipates them — in a way that doesn’t just cater to women’s sense of style, but kindles it. Michelle, a mother of two, credits Stitch Fix with “finally giving me a sense of style at 35 years old. I needed someone to hold my hand and show me how.” Or, as Lori, a 56-year-old from Illinois, told me, “I have no style or fashion sense. But I’m willing to try anything that my stylist sends me, and after nine Fixes, I have become so much more confident with my clothes. For the first time in my life, I’m getting complimented on my outfits.”

Katrina Lake describes stylists as a mix of “style professionals”: fashion school graduates, bloggers, and former boutique owners, all of whom go through a “rigorous recruiting and onboarding process.” How successfully Stitch Fix pairs its stylists and clients is unknown, as clients know little of their stylists save their first name and occasionally a last initial, and Stitch Fix declined my request to speak with a current stylist. The company did, however, provide information on Anne’s stylist: She’s 35, lives in Northern California, and is a former teacher and Stitch Fix client, and a mother to a 1-year-old.

Once the stylist assembles a Fix, she writes a brief note justifying her choices. One from earlier this spring featured nine exclamation points in nine sentences. (“I am excited to style for you again! I found you some work pants for your monthly work events; that will look beautiful with the Jalinda Cowl Neck Top!”) Each item is then “annotated” with style cards that suggest further styling strategies (how to dress up and dress down a cardigan; what to pair with “jogger jeans”). The client is notified via email that her Fix is prepped to ship, and the anticipation game begins.

It’s easy to conjure an image of an effortlessly fashionable woman sitting down at the computer and spending an hour acquainting herself with the details of your Pinterest, carefully curating a Fix from hundreds of potential selections. Many women on the 9,000-plus-member Stitch Fix B/S/T Facebook group believe that stylists secretly lurk on their conversations; others bemoan that they can’t send pictures of themselves dressed in their Stitch Fix fashions directly to their stylists. Anne told me that she’s often afraid of hurting her stylists’ feelings when she doesn’t like an item — a common sentiment among customers.

The reality, according to former stylists who agreed to talk on the condition of anonymity, is somewhat different. “It’s super boring,” one told me. “I could do 20 Fixes in an hour, but they only let you do four, so I’d just do them really quickly.” According to aggregated reports from Glassdoor, stylists earn $15 an hour, work remotely, and do not receive commission; Stitch Fix's official position is that "our stylists earn an hourly, market-competitive rate well above minimum wage, based on each stylists' role and individual experience."

Stylists aim for customers to keep two to three items per fix. When stock is low, the algorithm-created “closet” can sometimes be incredibly spare — another former stylist told me that she’d regularly have fewer than 10 items from which to pick. (Stitch Fix says that the number of clothing items from which the stylist selects a Fix is “proprietary information.”)

The most common frustration among clients is when a precise instruction, such as “Send me this specific blouse,” is ignored. In most cases, “ignoring” instructions likely has little to do with actual obstinacy: The Stitch Fix FAQ explains, “We carefully analyze our inventory so we know if a certain piece is ideal for a curvy woman or will be short for someone over 5’8". It’s these instances that make it difficult for us to handle specific item requests.” Put differently, the algorithm knows when your taste is misleading you.

Other customers bemoan Stitch Fix’s tendency “to dress me like a small-town secretary at a utility company or a recent divorcee who’s going out for her first time,” and the “Target quality for Anthropologie prices.” Last year, price concerns boiled over when a customer received a pair of shorts (Stitch Fix price = $68) with a $24.98 tag affixed from Nordstrom Rack. Stitch Fix offered a swift and plausible explanation for the “fluke,” but the story spread with alarming swiftness.

As damage control, Stitch Fix instituted a price-matching policy. Yet price matching Stitch Fix items is notoriously difficult: An ever-increasing percentage of items are produced by Stitch Fix’s six in-house brands, and the company modifies the names of other items to prevent easy googling. The Liverpool “Abby” Skinny Pant, for example, is rechristened the “Anita” Skinny Pant — a move that customer service claims is to add “a personal touch” to the merchandise.

Complaints about price, quality, and stylists’ failure to listen to precise instruction don’t pose an authentic threat to Stitch Fix’s business plan. The women most satisfied with Stitch Fix are those who recognize its value as a service: as a seamless source of style, of course, but also as a monthly diversion.

For Anne, a shipping notification means planning the 17-minute trip down gravel roads to the post office. From the day of delivery, she only has three days to return any unwanted items. There are months when her Fix has arrived and she’s been too busy to even try on the items before the return deadline. Yet Anne keeps her Fixes on a monthly schedule. “Packages are a lifeline out here," she told me. “I love the treat. It’s like how women in actual cities plan pedicures.” That feeling of specialness — so often absent from the contemporary shopping experience — keeps so many Stitch Fix consumers coming back, even when they’re not completely satisfied with the clothes.

That mind-set is potent among the 9,000-plus members of the Stitch Fix Facebook Group, which is devoted to modeling, discussing, and trading Stitch Fix items. Members are anywhere from 20 to 70 years old, almost entirely white, and span the country. The group generates more than a hundred posts a day, including a whole genre devoted to the pleasures and perils of “peeking,” or looking at the list of packaged clothes before they arrive.

Some openly chide peekers for their inability to enjoy the surprise of a Fix; others speculate that long shipping times are “almost like punishment for peeking.” One woman admitted to “going to extra lengths getting ready” on the day her Fix was to arrive; recently, members have begun hosting “unboxing parties” for those who live in urban and suburban areas.

But the most common post is a selfie of a woman, dressed in an item from her Fix, asking for feedback. The comments section on each post is a hodgepodge of advice, support, and warmth: When a woman posts a picture of herself in a newly received Stitch Fix skirt, admitting “my stomach is a trouble area,” for example, another responded, “You don’t need to lose 15 to look great in that skirt. Better? Maybe, but if you can and will wear it, I think you will rock it.”

It feels like the opposite of what one usually finds on the internet, especially percolating around women’s bodies and fashion. The group offers a crystallized portrait of the allure of Stitch Fix: It’s not about the clothes, or at least not precisely. It’s about a return to the experience of consumption as one of surprise and delight. For a group ostensibly devoted to buying and selling Stitch Fix items, money seldom even enters the conversation.

“There’s a pretty wide diversity in terms of the clients we serve,” Katrina Lake told me, highlighting their recent expansion into petites and maternity. “But we can’t be everybody to everyone early on.” Which is a polite way of saying that Stitch Fix doesn’t actually cater to plus-size women — 100 million of them in America alone. These women have long been considered “afterthoughts” of retail: Only recently has the market started to expand into the plus-size market, as retailers simply could no longer afford to not take their purchasing power seriously.

Stitch Fix’s refusal to cater to plus sizes has incited several disappointed and indignant blog posts. As of today, the company promises style, confidence, and delight to the American woman — but only 33% of them. Other fashion/tech retailers, including Le Tote, Tog + Porter, and Golden Tote, may eventually expand to the plus-size market, but like the vast majority of retail companies, they would still maintain the image of a “straight-size” company that just happens to cater to plus sizes. No matter that the plus-size market is a booming billion-dollar business — few new companies want it to be central to their brand.

That’s not the case for Gwynnie Bee, which offers the promise of an “unlimited" closet for the plus-size woman. “In the last 30 years, there’s been a real need for companies who serve women who have economic buying power, who want to look good and don’t believe they need to hide away until they lose the weight,” Gwynnie Bee CEO Hunsicker told me. In the three years since its launch, Gwynnie Bee has grown exponentially, and reviews are glowing. In a post titled “My Psychological Experiment,” one blogger exclaims, “I really am feeling sexier than I ever have in my life.”

Gwynnie Bee caters to sizes 10 through 32, offering a tiered monthly subscription model (starting at $35) that allows women to rent a dress for as long as she desires. Unlike Rent the Runway, which supplies one-time formal event wear, Gwynnie Bee provides items for everyday wear. When a customer is done with the dress, she simply places it in a return envelope; when it arrives back at Gwynnie Bee, it’s dry-cleaned and readied to ship out to the next customer.

A rental service is particularly well suited to women whose weight might be in flux. As Hunsicker put it, “Wherever you are in your journey — whether you’re going up, you’re going down, it doesn’t matter. We want you to feel beautiful and confident every day.”

Gwynnie Bee has enjoyed notable success; the company recently outgrew its Queens, New York, headquarters, and is in the process of relocating to Columbus, Ohio, where it plans to fill a 10,000-square-foot fulfillment center and expand to 400 employees. As of April 2015, it's shipped more than 1 million boxes. Gwynnie Bee does not disclose its funding publicly; by contrast, Stitch Fix has received $46.75 million over three funding rounds.

Part of the problem is that venture capital is almost entirely dominated by men — men who largely invest in ideas that speak to them. And if men find it much harder to feel inspired or passionate about “straight-size” women’s clothing, you can imagine the difficulties with sparking interest in the heavily stigmatized realm of plus-size fashion.

“I get it. You can’t blame investors for wanting to have passion in their work,” Katrina Lake told me. “But there’s just such an imbalance.” Lake continued with some PR speak on how that reticence ultimately allowed Stitch Fix to “focus on building a healthy business with long-term value.” But she also noted that the only way they convinced men — including Colson — to take notice was when their wives (or, in one prominent venture capitalist’s case, his assistant) started preaching the service’s gospel.

"There was an investor in our seed run and I brought in a Fix, showed him how it works,” Lake recalled. “He was just like, ‘I don't understand why anyone would ever want this.’ It really is hard, because Stitch Fix is not just about selling clothes. It's about this experience and personalization, and it appeals to women who are doing it all at work and then doing it all at home. There’s something about it — that emotional side of what is valuable about the experience — that’s harder to get people to understand.”

As fashion scholar Minh-Ha T. Pham explains, that lack of sartorial confidence is linked to so many female failings. Your marriage is broken because you’re not assertive enough to effectively communicate your needs. Your sex life is bad because you’re not self-assured in your own skin. Your job is unfulfilling because you’re not fearless enough to advocate for yourself. Stitch Fix, Gwynnie Bee, and a phalanx of voices, from What Not to Wear to Oprah, posit well-fitting, fashionable clothes as a solution. Get rid of the mom jeans, these services and programs seem to suggest, and Live Your Best Life.

That logic elides the larger, substantive reasons why women of all ages and sizes struggle to live their so-called best lives. The one thing that an algorithm can’t offer, after all, is perspective. And despite connotations of objectivity, algorithms and data science can be wielded to distort our sense of what’s “normal” or “ideal.” The intelligence of the algorithm, and its ability to speak a “truth” about an item of clothing, is firmly rooted in the subjective notion that a “straight-size” body is a standard body.

Fashion can be fun; it can be a wellspring of creativity; it can be generative and explorative, all of which provide a different sort of internally generated, as opposed to externally confirmed, confidence. But it remains unclear if fashion tech companies are enabling that attitude and experimentation — or simply bolstering a giant feedback loop that judges “good” and “bad” taste in terms of the financial and physical ability to dress your body a certain way.

Confidence, after all, is also what Anne says she most wants her daughters to take away from her own relationship with fashion. But for all of Anne’s love of Stitch Fix, the way she described that attitude had little to do with any service or stylist. “I want them to approach clothes with a sense of optimism and find their own groove,” she told me. “There’s time to figure this stuff out.”