Before the state of Georgia gave him a million dollars and before he lost it all, Clarence Harrison was convicted of rape and robbery and sentenced to life in prison in 1987. Years passed. His wife divorced him. He became estranged from his two young daughters. His mother died. He got cancer and had a kidney removed. He lost hope. He stopped communicating with everybody on the outside. He resigned himself to spending the rest of his life behind bars and being buried in the prison cemetery, which inmates called Pissant Hill.

Then in 2004, 18 years after he was arrested, a DNA test proved that he was innocent.

Harrison and his lawyers believed that the process to get him released would take up to two more years. There were prosecutors to fight and motions to file, and that was how long the process had taken for other innocent inmates.

A week after the DNA test, Harrison was transported three and a half hours from Smith State Prison to the DeKalb County Courthouse in Decatur. He assumed it was for a routine evidentiary hearing. Then the judge said he was free to go.

Cameras and reporters waited for him on the courthouse steps. Microphones surrounded him and he spoke the first thought that came to his mind:. "The first thing I'd like to do is get my job," he said, because he hoped to marry the woman he had met and fallen in love with while he was incarcerated "as soon as I can get a job and earn the money to buy the ring."

The exoneration was a lead story in the local news. People all around the greater Atlanta metropolitan area stepped forward to donate suits, dresses, flowers, and a wedding ring. Less than three weeks after he walked out of that courthouse, Clarence Harrison was married in a church in downtown Atlanta in a ceremony paid for by strangers and filled with people he barely remembered and people he had never met, all there with smiles and well wishes.

Eight months later, the Georgia legislature passed a bill to award Harrison $1 million for his wrongful imprisonment. It was the first time the state had ever offered to compensate an exoneree.

Harrison moved into his wife’s house in Marietta, 20 miles north of Atlanta. A board member of the Georgia Innocence Project offered Harrison a job at the bookstore she ran. A musician released an album inspired by Harrison’s experience. One local pastor described his exoneration as, “a story that shows God’s transformative justice in making things right.” It is a story that has been on the front page of the Atlanta Journal Constitution, on Good Day Atlanta, on Al Jazeera, on CNN.

Clarence Harrison had love, money, and freedom. He was the star of a real-life fairy tale.

“That’s that happy ending part,” Harrison said.

He did the media circuit for a while, but soon the attention faded away. Reporters stopped calling. There were new injustices and redemptions to cover. But when the lights turn off, an exoneree’s struggle is just beginning. And all that happened over the next decade — Harrison refers to it as “the story they don’t hear.”

In the story they don’t hear, the $1 million is gone, the future annuity checks aren’t coming, Harrison is jobless and depressed and broke, can’t get disability payments, owes the government tens of thousands of dollars in taxes, and has no idea how to get his life back on track.

“Ain’t no justice in my release if I’m going through what I’m going through,” he said. “They don’t understand. People shy away from that stuff. People don’t wanna hear that. They want the Cinderella. They don’t understand there is tragedy behind it. I can’t tell ‘em how good I feel to be out. I don’t feel good about being free.”

People didn’t want to hear about his life before the arrest, Harrison believed, and so he didn’t tell people about it. He was the second youngest of 10 kids, raised by a single mother who worked as a housekeeper. He didn’t really know his father, who died when he was 7.

“Only two memories I have of him,” Harrison said. “One was in the kitchen pouring liquor, and the other was at the card table.”

Harrison got kicked out of four high schools. After dropping out, he supported himself by stealing clothes from department stores and selling them on the street. At 18, he got married, had a daughter, and moved the family into an apartment, out of which he ran a gambling den to pay the rent.

One night, while 18-year-old Harrison and a few friends were out on a beer run, one of the friends pulled out a gun and robbed a woman. They were all arrested, and Harrison spent the next six years in prison for armed robbery. Back out at 24, he had another daughter and vowed to turn straight. He worked construction, then tarring roads for DeKalb County. He cashed his checks as soon as he got them, and stored his savings at home.

“I was happy,” he said. “I worked. I provided.”

Less than three years into his new life, he was arrested for rape and robbery, and this is where the fairy tale begins.

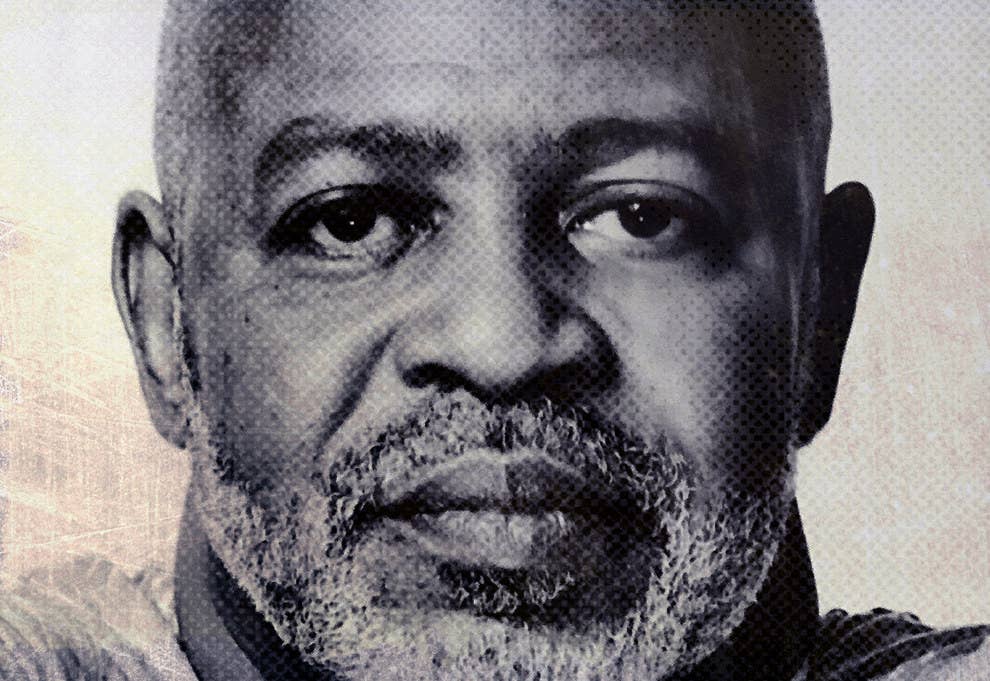

Harrison, who is 55 and walks with a cane, speaks softly and with poise, and in the same conversational drawl before a roomful of law students as on a barstool around old friends. He likes to weave in the details. Speaking on a panel at Emory University in February, he recalled that on the night of the crime he had been playing poker, then tossed in a digression about how much he loved to gamble and how when he was in prison nobody was sending him money but he survived by winning snacks and weed and cash in card games. He noted that the victim, who identified him as the culprit, was so-and-so’s boyfriend’s sister. And he described the moment the judge read the guilty verdict, how he looked around the courtroom in a daze.

“I’m still looking for that superhero that’s gon’ correct it,” Harrison said. “But he didn’t come. And when I looked around for my superhero, I saw my mama’s face and she was crying.”

At its heart, though, the story Harrison tells audiences is a love story, one that just happens to be bookended by a wrongful conviction and an exoneration. A fellow inmate had phoned his girlfriend but her mother picked up and was giving him a hard time. So, in a rush to get off the line, he passed the phone to Harrison and asked him to occupy her. The conversation sparked something between them, and soon Yvonne was mailing him letters.

By the time he first spoke to Yvonne, Harrison had already given up hope. He had appealed his conviction only to learn that all the evidence in his case had been destroyed because DeKalb County had a policy of cleaning out its evidence rooms by dumping files after seven years. The DNA that had been in the file had been deemed contaminated and therefore untestable. The news broke Harrison.

“I just accepted the fact that I was never gonna come out and be in society again,” he told the students. “And at that point I stopped communicating with my family. I wouldn’t let them write, wouldn’t let them visit me. I wouldn’t call anybody. I didn’t wanna have any part of the so-called free world. I wanted to accept that that’s where I was gonna live and die, in prison. So I shed the outside world. And I stopped trying to fight.”

But Yvonne encouraged him to keep fighting. She read his trial transcript and told him she believed he was innocent. She took a third job to pay for his lawyer, but the lawyer couldn't make any progress on the case. She did some research and persuaded him to write to the Georgia Innocence Project. Aimee Maxwell, the nonprofit’s executive director, and her two staff members took on his case.

One of Maxwell’s lawyers visited the county evidence room, looked through Harrison’s file, and found a brown paper bag containing a single slide of DNA evidence that nobody had noticed before. They sent the slide for testing, and the lab discovered that the sample was indeed testable, and that it belonged to somebody other than Harrison. Police never found who the DNA belonged to, and the crime was never solved. But the District Attorney’s Office agreed that the evidence proved Harrison’s innocence, and next thing you know Clarence and Yvonne Harrison were standing at the altar in Atlanta’s most celebrated wedding of 2004.

“Any place we would go in the city people would go up and talk to him,” Maxwell, who was also on the panel, told the audience. “His story has inspired people.”

Donations covered every bit of the ceremony, and the honeymoon too.

“The entire city of Atlanta — it’s one of the most inspirational things of the whole story — the city of Atlanta came together,” Maxwell said. “He’s still married. They’re still sort of like 14-year-old kids in love.”

By Clarence Harrison’s estimate, he has told his fairy tale “hundreds of times.” It's a kind of story that is getting ever more familiar.

In the three decades since his arrest, it became clear that wrongful convictions were more common than most Americans ever imagined. In 1986, no conviction had ever been overturned because of DNA evidence and exonerations were so uncommon that no organization had bothered to keep track of them. But after the first DNA-based exoneration in 1989, there was a growing body of evidence that eyewitnesses were sometimes wrong, confessions were sometimes false, and an untold number of innocent people had been locked up in the push to get tough on crime. Fifty-seven people were exonerated the year Harrison was freed. In 2012, 92 people were exonerated, and 91 more were exonerated in 2013, according to data collected by the National Registry of Exonerations. In 2014, there were 126 exonerations. Every year there are more Clarence Harrisons.

As the number of exonerees has grown, state legislatures have moved to pass statutes that guarantee financial compensation for the years of wrongful imprisonment. In 1986, five states had compensations laws on the books. In 2006, 11 did. By the end of 2014, 30 states had such policies. Across the board, there is almost no disagreement over whether states should give money to exonerees — the debate is simply a matter of scope, of how much to pay and of how to close loopholes that might send money to guilty people freed on legal technicalities.

Different states treat their exonerees differently. For his 39 years of wrongful imprisonment in Ohio, Ricky Jackson got a total of $1 million, or around just $25,600 per year. The Central Park Five, who each spent between seven and 13 years locked up, received $1 million per year of imprisonment in a settlement with New York City. Texas, widely praised for having the most benevolent compensation policy, gives exonerees $80,000 for each year of incarceration. New Hampshire caps total payments at $20,000. Other states don’t offer compensation if an exoneree pleaded guilty, or unless they were freed by DNA evidence.

Twenty states have no compensation laws. In those states, an exoneree’s only paths to restitution are to sue the state, or, as in Georgia, to lobby for an individual bill granting compensation. All in all just two-thirds of DNA exonerees receive compensation, and the rate is even lower for those who were exonerated without DNA.

“This whole social phenomenon of wrongfully convicted people is a relatively new phenomenon,” said Marla Mitchell-Cichon, a professor at Western Michigan University’s Cooley Law School. “And we’re still struggling as a society and in the law to figure this out.”

Even most states that provide compensation offer nothing beyond money. While a person on parole usually gets job training, psychological counseling, financial guidance, and perhaps a bed at a halfway house, almost all exonerees receive no support as they leap into the icy waters of the free world. The transition can be overwhelming, and an exoneree is left on his own to get his life back in order. There are the nightmares, the waking up terrified of being back in prison. There’s the adjustment to physical contact, a sign of aggression on the inside but of comfort on the outside. There’s the anger, always lingering in the back of the mind, for the years taken away. There’s the fear of never being able to fully rejoin society.

Joseph Frey, who spent 11 years in prison in Wisconsin before his exoneration in 2005, lived in a homeless shelter for weeks after his release. Ken Wyniemko, who did a nine-year bid in Michigan before his exoneration in 2003, couldn’t find a job, and when a bowling alley owner was about to hire him, employees threatened to quit because they weren’t convinced he was innocent. Calvin Johnson spent 16 years in prison in Georgia before his exoneration in 1999. Lacking a credit history because of his time in prison, when he tried to rent an apartment, the property manager told him he had to pay triple the security deposit.

Nationwide the vague idea of “criminal justice reform” has emerged as a front-page domestic policy issue, and within that conversation the specific idea of compensating exonerees has emerged as a priority. In Georgia, Harrison is the face of this movement, and there has been an increasing demand for his voice. Over a two-week stretch in February, Harrison had five speaking engagements, all unpaid, not counting the ones he had to turn down because he couldn’t get a ride.

He didn’t mention the million dollars in any of them. During the Q&A portion of the Emory event, a student asked whether exonerees like Harrison could get any money for the years they lost. Harrison didn’t speak up, so Maxwell took the question. She explained that, though Georgia has no compensation statute, the state legislature can pass individual bills to award exonerees $50,000 for every year they spent in prison, and that’s what Harrison got: $1 million in total, handed down in yearly annuity payments from 2006 to 2024. Then she rattled off the policy changes she and other advocates were pushing for.

That evening, back home in Marietta, Harrison thought back to that moment in the event and said, “When he asked that question, about the money, I wanted to tell him so bad about what it’s really been like, but I couldn’t.”

Here’s what it was really like.

The first thing Harrison noticed back in the free world — or the “so-called free world,” as he always puts it — were the roads. The three-lane highway he remembered was now a six-lane highway. He noticed the cars too. “‘Cause, you know, we had them big Caddies, and these things were like little space ships,” he said. He noticed that gas stations were now self-service, and he had to watch other people pump their gas to figure out how to do it himself. The most shocking thing he noticed, though, was how expensive everything was. Last he remembered, a burger cost a dollar and change and now it was close to five bucks. The impact of inflation is especially apparent when you jump straight from 1986 to 2004.

Harrison knew he was luckier than most exonerees. He had old friends supporting him. He had a wife to help take care of him. He had a home to move into. He was able to get three jobs: stocking shelves for a bookstore, filing documents for a bail bondsman, and working security at a school. And he had money to fall back on. Harrison had $47,368.40 coming in every July 31 through 2024.

The first thing he bought with his compensation cash was Yvonne’s dream car, a black Chrysler 300.

“I jumped up and down,” said Yvonne.

“Best money I ever spent,” said Harrison.

Then he got himself a black Ford F-150. He took in three grandchildren as their parents struggled to make ends meet. He gave money to anyone who had supported him while he was locked up. When a friend or relative couldn’t make rent or was behind on car payments or didn’t have enough to buy groceries, Harrison took care of it. Twice, he bought a car for relatives who needed one. And loved ones weren’t the only beneficiaries. He handed cash to acquaintances and strangers from his old neighborhood who had fallen on hard times. He likened himself to a first-round NBA draft pick who suddenly hears from long-lost cousins and classmates in need of some funds.

“Clarence, he’ll take his drawers off if you wanted it, and he’ll walk around butt naked,” said Yvonne.

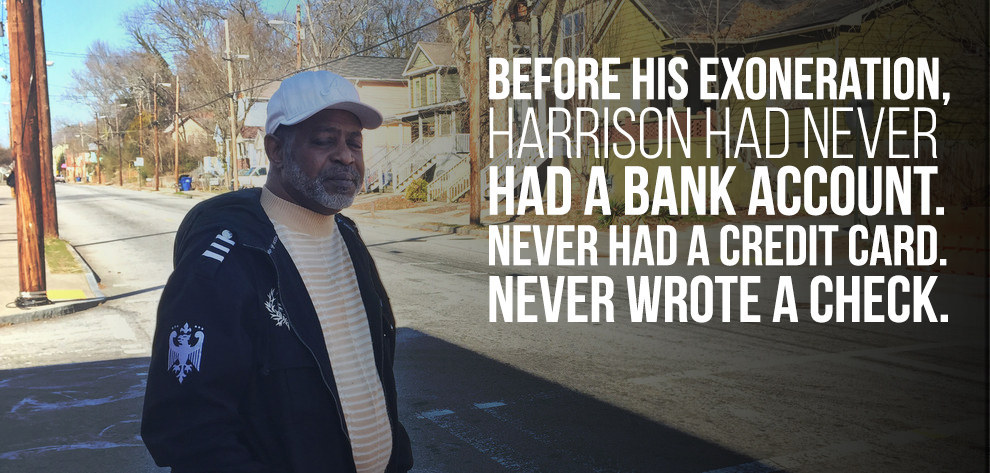

Before his exoneration, Harrison had never had a bank account. Never had a credit card. Never wrote a check. He didn’t learn to read until he got to prison and took a GED program. He was financially illiterate when he returned to the so-called free world. Suddenly, close to 50, with a family to provide for, and $1 million in annuity to his name, he had to figure it all out. Within months of Harrison’s release from prison, he had started receiving credit card offers in the mail exclaiming that he was “Pre-approved!” He got three cards and maxed them out. When Yvonne saw the bills, she said, “You gon’ pay all that money back?”

“Nah,” he replied, “whoever pre-approved me gon’ pay that money back.”

And then she explained to him the concept of a credit card and that “pre-approved” did not mean the same thing as “pre-paid.” He owed nearly $20,000. Because he had no credit history, his cards were set at 30% interest.

He also got in the mail dozens and dozens of letters from companies offering to give him cash in exchange for the rights to future annuity payments. One solicitation, from Peachtree Settlement Fund, came with a flier warning about “the shrinking value of a dollar over time.” A chart showed that a dollar in 2005 will be worth 15 cents in 2025. “Think about it: a loaf of bread that cost $1.25 merely fifteen years ago costs $2.50 today,” the sheet stated. “It is clear that tomorrow’s money is worth less than today’s.”

This wasn’t news to Harrison. He understood this fact better than most. He remembered that $5 burger. The Peachtree sheet made a lot of sense. And with those high-interest credit cards bills, he knew enough to know he should pay them off as soon as possible. So in October 2008, Harrison sold $54,000 worth of annuity due 2009 and 2010 for $43,688, according to financial documents reviewed by BuzzFeed News.

“That’s when I really messed up,” Harrison said. “When I started doing that junk.” Like a lottery winner who goes bust, Harrison found that he had not escaped the kind of money problems he thought he had left behind.

The cash was helpful. He paid off his cards. He got ahead on the mortgage on his and Yvonne’s house. He repaired water damage in the house and renovated the interior. He paid off medical bills for treatment he had gotten for complications from losing a kidney.

After the recession hit, the bookstore closed down and Harrison left the bondsman job during a round of layoffs. He didn’t mind. He had bigger plans.

One day in 2008, he was kicking it with friends in Pittsburgh, the Atlanta neighborhood where he grew up. He saw an old woman lugging a load of laundry down the sidewalk, and he asked his friends where she was taking it to. His friend told him she was probably headed to the laundromat more than three miles up the road. Harrison asked what happened to the laundromat around the corner, the one across the street from his old elementary school. Closed down after the owner died two years ago, they told him.

Harrison contacted the man who was renting out the laundromat building, and the man told him he was behind on lease payments and couldn’t afford to open it back up. Right then Harrison knew what he wanted to do with his money. “Pittsburgh Community Laundromat,” he named it. Because “it wasn’t my laundromat,” he said, “it was the community’s.”

The streets and sidewalks of Pittsburgh, Georgia, were empty on the February afternoon Harrison dropped in. He had an event in Atlanta that evening and had a few hours to kill. He walked to the corner where the laundromat stood, beside a lot it shared with what New Yorkers would call a bodega. At the base of an iron gate next to the corner store, a memorial for the 62-year-old man shot dead a few weeks before. On a gate behind the store, a teddy bear memorializing the 20-year-old killed a few weeks before that. Lots of things had changed over Harrison’s 18 years on the inside, but some things hadn’t.

“The hood stay the hood,” Harrison said.

It had been eight months since his last visit, and when he stepped into the corner store, it was magic. Several men standing by the counter lit up. Like Obama or Andre 3000 just walked in.

“Oh shit! Pimp C!”

“What up, Mr. C!”

“I been missin’ you, baby!”

“Ohhh snap! Unc!”

Hugs and handshakes all around. Harrison saw the whole crew that day. Five Star, Wood, Butch, Sarge, Cut, Ty. Behind the counter, Five Star smiled and shook his head in euphoric silence.

“This fuckin’ guy,” he whispered, still grinning, as he slapped hands with Harrison.

Soon the Heinekens were out and Black & Mild smoke snaked to the ceiling despite the “No Smoking” sign posted in the back in red marker. Five Star pulled out a bottle of Bacardi and several paper cups.

“Don’t be tryna get me drunk,” Harrison said to him. “I gotta speak later! I want a lil’ shot. Don’t give me no big one.”

But Five didn’t listen. There were memories to discuss.

After Harrison took over the laundromat in 2008, he turned it into the most happening spot in the neighborhood. He’d quit his security job to work at the laundromat full time. Over its first year in business, he sold three more years of annuity in four separate transactions with Peachtree. He bought out his partner for $20,000. He installed new washers and dryers, which churned out clothes faster than the old ones and brought in more customers. He installed a dozen slot machines in the back, which brought in even more customers. Every kind of shop in Pittsburgh had slot machines in the back, but Harrison set his to have lower odds, and every local knew Pittsburgh Community Laundromat was the place to go to win some money.

On each of the annuity transaction contracts, Harrison signed his name to a waiver acknowledging that he had not consulted with any financial professionals. The further into the future the annuity check, the less cash he got for it. He hadn’t done the math on the exchanges, but he wasn’t concerned about selling off the annuity. He saw limited value in those far-off checks. He was a cancer survivor on the other side of 50, with one kidney, sleep apnea, and many years of cigarette smoking and hard prison living behind him, and he had two decades of living to catch up on.

“Ten years? I dunno if I’mma be here in ten years! Fuck ten years,” he said.

The lump-sum offers kept piling into his mailbox. “Time sensitive” offers guaranteeing the cash as soon as the court date to approve the transaction is set. How quick and easy it is to get the $15,000 you need with Seneca One! In October 2010, he sold Seneca One Finance future payments totalling $120,320.10 for $19,163.92 cash. He put the money into the laundromat. He would expand it. He would set up a beauty salon inside and fix up the building so it would really be first class.

By fall 2010, Harrison’s business was running smoothly. He made $5,000 a week off the slots, and all together he was pulling in nearly $100,000 a year in revenue. Most of his profits went into the cookouts he hosted in the lot every weekend. Brought the whole community out. Sometimes even brought in a few outsiders, like the time he threw a party for all the Georgia exonerees.

“Over in the hood you had lawyers, judges, imagine that,” he said. “It was good. Nobody’s car got broken into, nothing. All the gangbangers kept it cool. Everything cool.”

After the cookouts, Harrison and Five and the rest of the crew would take the party into the corner store. Five still had the pictures on his phone, and he pulled them up, drawing laughs when he got to the one of Harrison passed out on a chair in the back of the store. Some nights, they extended the party to the club, and the men in the store recalled that time Wood got kicked out for getting too handsy with a dancer.

As the old friends spoke, others entered the store, and each one did a double take upon seeing Harrison, and there were more hugs and handshakes.

“This why I love that man,” said Ty. “He a generous man for all that stuff he went through. This man would feed the whole neighborhood. He don’t care if he know you or not. He make sure you eat.”

“Then bullshit happened,” Ty added after a pause.

“Who holdin’ up in the laundromat?” Harrison asked.

“Nobody,” said Five.

“It closed,” said Wood.

“Wasn’t getting no business,” said Five.

Harrison looked to the ground, shook his head.

“Closed like it was when I first saw it.”

The “bullshit” happened in November 2010, when Harrison’s car stalled on an icy road as he headed home around midnight. He got out of the car and walked up the road toward the nearest service station half a mile away. Halfway there, a car heading in the opposite direction slid on the ice and hit Harrison. He was barely conscious enough to see the driver get out of the car, look at him, then get back into the car and drive off, never to be caught.

He was laid up at the hospital for a month and unable to walk for several more months after that. His wrists had been broken, he had a metal rod inserted into his leg, and he had his hip replaced. The laundromat shut down. He didn’t have enough saved up to keep paying the lease, and he wasn’t comfortable having somebody else look after the place in his absence because it was a dangerous neighborhood and he couldn’t bear the thought of somebody getting shot in his laundromat because he wasn’t there to protect them. Yvonne’s insurance covered some of the hospital stay and the physical therapy. The remaining $50,000 was billed to them.

Around this time, Harrison received a letter from the IRS stating that he owed $90,000 in taxes. He had not known that he had to pay taxes on his annuity. Nobody had told him, he said. Over the years, he had only listed his work income on his tax filings. And over those years, his debt to the government was building. He consulted a lawyer. The lawyer told him that if he did not pay down the back taxes on the money he had gotten for his wrongful imprisonment, he would go to jail.

And so he sold Seneca One future payments worth $331,582.30 for $105,599.93.

By the middle of 2011, Harrison was broke, jobless, barely able to get around his own home, and in deepening debt with the government. He learned that he owed taxes on the original amount of each annuity payment, rather than on the cash amounts he had sold them for. This meant he would continue to owe taxes on annuity checks he was no longer receiving.

“When they hit him, that took a lot from our household,” said Yvonne. “All of it fell on me. And half the time my paycheck ain’t enough to make ends meet.”

They shuffled bills. Sometimes the lights went out. Yvonne’s Chrysler 300 and Harrison’s F-150 were repossessed. His grandchildren moved out and back with their parents. Harrison applied for disability, but the Social Security Administration rejected his claims and said that his injuries were not serious enough to quality.

“It’s frustrating you can’t provide for your family,” said Harrison. “I ain’t come out of prison for that. I ain’t come out to be dependent on her.”

They fell behind on mortgage payments. Harrison worried they would lose the house. In November 2011, seven years after his exoneration, Harrison sold the rest of his annuity to Seneca One, $94,736.80 for $18,850.69. He paid off the house.

All in all, he had traded $735,000 of future payments for $272,000.

Nobody can truly understand what it’s like except for those who have been through it. And so when those who have been through it gather, there is a calmness, the reassurance that you are not as alone as you sometimes feel. Harrison and a few other Georgia exonerees get together every few months. There’s Calvin Johnson, 16 years. There’s Robert Clark, 24 years. There’s John White, 27 years. There’s Pete Williams, 21 years, but Pete rarely makes it out anymore.

“We got a real close bond,” Harrison said. “We more comfortable around each other than we are with other people.”

When they gather they get to talking about “the stuff we don’t get to talk about,” Johnson said. They talk about prison. They talk about the struggle to transition, a struggle harder than all of them had imagined. They talk about how the compensation money did not help as much as people think it did, and about how they can’t say this publicly because it would make them seem ungrateful, and anyway nobody would understand.

One evening in February, Harrison and Johnson sat in Harrison’s living room sipping beers. The Hawks game was on, and they kept their eyes on the TV as they spoke.

“Shit, I missed some good years,” said Johnson. “Eighties and nineties? That’s some good years.”

“Twenty-five to 40, that’s your prime there,” said Harrison. “Whatever a man gon’ be, that’s where he becomes it right there.”

They traded stories about those prime years, the ones spent in Georgia state penitentiaries. The fights, the poker games, the friends.

“Them my good days,” said Harrison. “Sometimes I wanna be back in there. I ain’t lyin’.”

Johnson quietly nodded in understanding. Johnson knows he has had a blessed transition back into the so-called free world. He had a college degree before he was convicted, and after his release he had no trouble finding a job. He is now a superintendent for the local transit agency, where he has worked for 15 years, making more than enough to live comfortably in Georgia. He has a big house in the country with a wife, kids, and three dogs. He wrote a book about his experience. He has traveled as far as Uganda to tell his story. He used to make regular trips to New York City, paid for by the New York Innocence Project, which handled his case and raises a good deal of donation money. He was Georgia's first DNA exoneree, before Georgia had ever offered to compensate, and so he got his money through a lawsuit settlement: $500,000, in a one-time full payment, with the taxes already sliced off.

“Mine’s of more on the fairy tale side,” Johnson said. “The average on the whole is more like Clarence.”

Johnson and Harrison discussed their friends John White and Robert Clark. Both were struggling. Neither had a job. One moved back in with his parents.

“My biggest concern for a lotta these guys is all those years we were locked up we weren’t getting anything taken out for social security,” said Johnson. “What kinda retirement is coming? They ain’t finna have nothing.”

“Even though we was working the whole time we was in there,” said Harrison. “Ain’t none of that counts, though.”

But Harrison didn’t talk about that in front of audiences. Just like he didn’t talk about the car accident, and the tax problems, and especially not his armed robbery arrest when he was 18. Aimee Maxwell, the Georgia Innocence Project director, said that it was Harrison's choice not to mention these portions of his life and that the nonprofit would be grateful for whatever story he told. Harrison, though, didn’t think the Georgia Innocence Project wanted him to get into all that.

“I ain’t never been no goody-two-shoes,” Harrison said with a chuckle. “I guess it matters to them because they looking for support, donations. People gon’ think they getting criminals out of prison. Instead of innocents, they getting criminals.”

All over his house are the relics of his goody-two-shoes image, the image that serves as the face of exoneration. On his living room wall, the framed Atlanta Journal Constitution article about how Yvonne kept the faith in his innocence. On his fridge, the Good Day Atlanta photo, signed by the hosts, one of whom scribbled, “You’re an inspiration to us all.” On his computer, the CNN clip, headlined “Exonerated Man Makes Music,” about the two musicians who recorded an album based on Harrison’s story. CNN licensed a song from that album for a commercial promoting its documentary series about death row inmates. According to singer Melanie Hammet, between the licensing fees and live performances and album sales, the music has raised around $80,000, with all the money going to the Georgia Innocence Project. In August, the Georgia Innocence Project threw a big party to celebrate Harrison’s 10th year of freedom. Tickets were $55, and all the proceeds went to the nonprofit. And that’s on top of the attention and goodwill Harrison has brought the organization through his hundreds of appearances.

Some exonerees charge speaking fees, and a few of them have told Harrison he is a fool for not seeing a penny from any of his time and effort. And sometimes Harrison wonders if he is a fool for doing so much for free while he and Yvonne can’t even keep up with the bills. He wonders if he is a fool for keeping up the smile for people who will never understand his pain. He wonders if he is a fool for performing his fairy tale over and over again while there is tragedy behind the curtains.

The thoughts crossed his mind as he prepared for another trip into Atlanta for another event, this one with the Urban League and the National Action Network. His brother had just gotten him a stack of bootleg DVDs and Harrison would’ve much rather plopped on his recliner and spent the evening watching sci-fi flicks. But instead he put on his coat and limped out the door.

“Man, I ain’t really in no mood for this,” he said.

And so he was relieved when Maxwell told him that he should keep his remarks short tonight, to around five minutes, so that the program wouldn’t run too long.

Then he began speaking. Five minutes in, he had not even gotten to the part of the story where he goes to trial, and he went on and told the story he tells all the way to the end. Because no matter the circumstances of his life, this is a message he believes in and it is greater than him. And so no matter how much he craves to tell the world that his life is not a real-life fairy tale, he holds back.

“I don’t wanna burden people with my problems,” he said after the event. “I don’t wanna give negativity. I wanna give other people hope. There are people out there who need to hear it. I don’t wanna burden them with my problems.”

Several exonerees had been invited to that night’s event, but, as usual, Harrison was the only one to accept. He understands the power of the story he tells. He knows it brings in money that will help other people, and not help him, but he has been where those people are and he knows they need the help more than he does.

“I still know there are other people who need to get out,” he said. “And if I don’t do it who will?”

After the event, he went to the corner store in Pittsburgh. It was late, and music was blasting from speakers and people were drinking beer. Five Star popped a beer for Harrison and Butch passed him a Black & Mild.

More customers entered the store and joined the party. Almost every one told Harrison that he should open the laundromat up again. The community needed it, one said. We gotta have you back here, another added. But Harrison knew that was impossible. There was no happy ending, not at this moment at least. And the more he told his fairy tale, the more he hungered to tell the world the real, sad, ongoing story.

“Life ain’t no merry-go-round,” he said. “There’s a struggle part. People say I blew my money. I ain’t blow nothing. That wasn’t on me. That was on tryna get my life straight. ‘Cause I was taking care of so many people, they thought I just spent it.”

“It wasn’t like that at all,” said Sarge.

“Life costs money,” said Five. “You could spend money without even doing nothing. You spent 17 years in prison. You gotta have some fun.”

“You need to live,” said Harrison. “That’s what freedom was about. Just living.”

The men stared at their beers in silence for a few seconds. Then somebody mentioned the Hawks and the vibe picked up. Five turned the music louder, and Sarge began freestyling over the beat. Heads bobbed. Harrison swayed his hips and rocked his shoulders. He nodded at Five Star. Another Black, another beer. Just living.