Lately, Laura Dunn has tried to avoid thinking about rape on the weekends, but it doesn’t come naturally for the meticulous lawyer. Her idea of unwinding includes binge-watching Law & Order: SVU, not exactly light entertainment for a woman whose weeks are spent fielding calls and emails about the very topic — sexual assault — that dominates the show. For Dunn, though, this world of virtuous detectives and prosecutors is an escape from the calls and emails she receives from people asking for help, from the start of her workday at 8 a.m. until she’s collapsing into bed around 11 p.m. People who’ve been raped, people whose children were raped, people whose reports of rape were ignored and who finally got fed up enough to do something about it.

People like Laura Dunn.

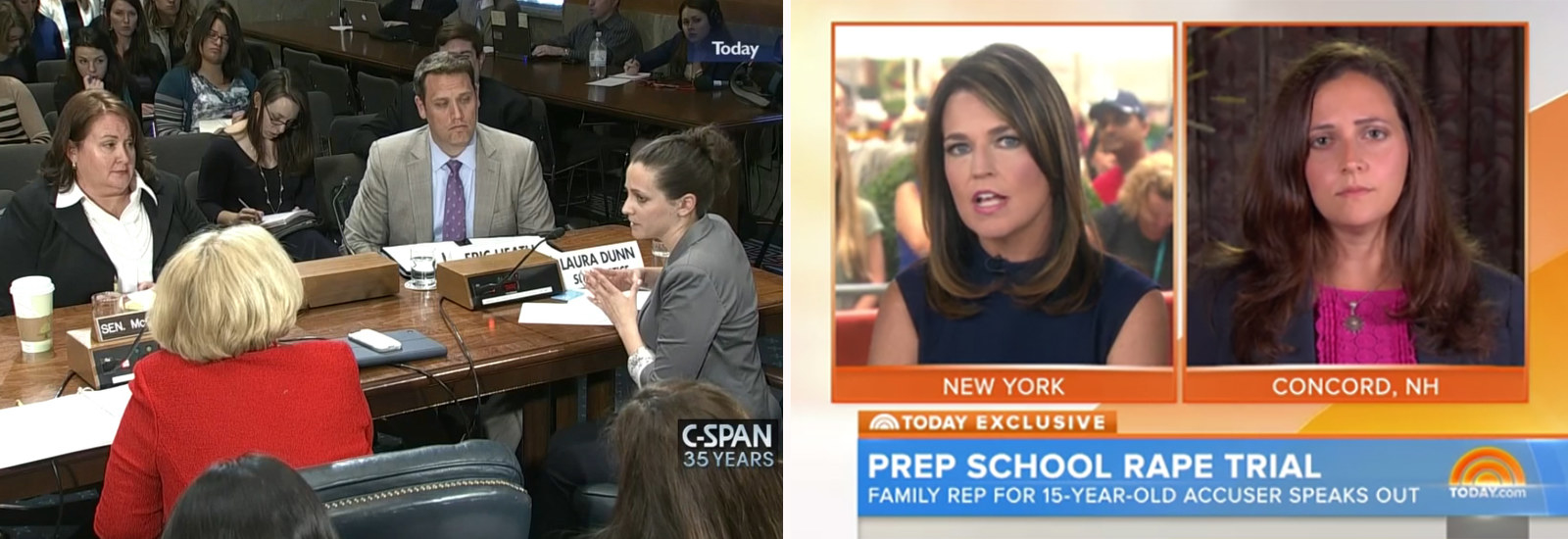

If you saw Dunn, 31, walking along K Street with her shoulder-length brown hair draped over her blazer and modest blouse, you might take her for a young civil servant in the federal government, toeing the line of some older white guy. Dunn is nothing of the sort. She runs SurvJustice, a nonprofit that in its brief lifespan is credited with ushering in at least 120 federal investigations of schools around the country. She spent time at Joe Biden’s official vice presidential residence, and one of Biden’s former advisers, Lynn Rosenthal, sits on SurvJustice’s board. State and federal lawmakers ask her to endorse legislation. Still, Dunn wants more. Much more.

“I’m always mad that we’re not bigger,” said Dunn, matter-of-factly. “I want to be Gloria Allred big. People know if your civil rights get violated, you go to the ACLU. I want people to know if you get raped, you go to SurvJustice.”

The nation reckoned with sexual violence like never before during Barack Obama’s tenure, due in part to actions taken by his administration, but more so because of survivors coming forward about what had happened to them. Women stood up against the famous men they say abused them, like Bill Cosby or Darren Sharper, and hallowed institutions like Penn State and Baylor University were publicly accused of prioritizing football above stopping sex crimes on campus. So much progress was made discussing rape that many pundits and writers — including Dunn — assumed Donald Trump, a man widely condemned for describing how he would commit sexual assault, could never be elected.

Trump’s victory wasn’t just a cultural shock for people like Dunn. It brought fears that his administration would roll back enforcement of federal rules intended to help campus rape victims. An even bigger worry for many advocates is that they’ve just lost a president who spoke out against sexual violence and who has been replaced by one who defended his own misogyny as “locker room talk.”

“I did not picture any alternative to Hillary winning,” Dunn said. “So I was surprised and it did cause some panic — everything I’ve spent years working on already may get pushed back. It was definitely something I personally mourned.”

SurvJustice, which Dunn started in 2014, provides legal help to women and men who have been sexually assaulted, mainly on college campuses. Decades of research have come to the same conclusion: that around one-fifth to one-quarter of all women will experience some form of sexual assault — from battery to rape — by the time they graduate college. A national Washington Post–Kaiser Family Foundation poll came to the same conclusion in 2015, as did a national survey of 150,000 students at 27 campuses.

Dunn lives in Washington, DC, to stay involved in federal policy. SurvJustice’s new office is a reflection of Dunn: practical and unfussy, with few things on the walls and a potted tree in the corner. It’s on 15th Street, around the corner from the White House. It served as a meet-up spot for herself and a few others for the Women’s March last month, 850 miles from the ultra-conservative Madison, Wisconsin, home where she grew up.

Dunn, the youngest of four children, was a confident child who coolly planned her life and dreamed of becoming a prosecutor. Her mother, Vicky, recalled that when her daughter was getting ready to start ninth grade, she vowed to earn 12 varsity letters in high school, which turned out to be exactly how many she won. “What Laura decided to do, she would actually follow through on,” Vicky said.

She went on to college at the University of Wisconsin–Madison, joined the crew team, and appeared to be off to a good start.

In July 2005, Dunn, who had been living on campus, arrived back at the family’s house after her sophomore year and took her mother aside. She had to talk to her about something. Then Dunn, 19 at the time, told her mother that after a night of drinking with two guys on the rowing team her freshman year, she had gone back to an apartment with them. There the men raped her, she said.

Her mom rushed from the room and grabbed Dunn’s dad. “Laura’s dad was always her strong person,” Vicky explained. Vicky stayed back around the corner and listened as a hysterical Dunn shared what had happened to her — “just agonizing, words flowing, screaming, a lot of crying,” Vicky said, “and I couldn’t really bear to see that.”

Dunn’s parents are religious conservatives, members of an Evangelical Free church. Her parents demanded she leave UW–Madison and either transfer to a college of their choosing or become a religious missionary. They threatened to cut her off financially if she stayed at the university, said Dunn, who 11 years later became visibly frustrated as she recounted the conversation.

”They wanted me to be closer to God because they thought this school, this liberal school, had a negative effect on me, and that’s what led up to all of this,” Dunn said. As Dunn tells it, her parents considered her a sinner: “They had this idea I had brought shame on the family.”

Instead of doing what her parents wanted, she returned to UW–Madison. “And that was one of the most painful moments of my life,” said Dunn. Back on campus, she cried in her room as she worried about how to repair the rift with her parents — and how to pay for her own tuition. Her parents didn’t end up cutting her off — her father later called and said he admired her for standing up for herself.

“We were really in a highly protective mode,” Vicky explained. It became clear pretty quickly, Vicky said, that Dunn wasn’t going to bow, even though she saw one of these accused men on campus regularly. Vicky recalled that Dunn’s attitude was, “Why should she have to leave?”

That attitude still drives Dunn. “She has no problem staring down anybody and everybody,” said S. Daniel Carter, SurvJustice’s board secretary. Carter said Dunn knows all too well what it’s like to be doubted by friends, blamed by family members, and let down by her school.

It took Dunn over a year to report being assaulted to the university’s dean of students and the UW–Madison police, which she did in July 2005, shortly before telling her parents. By that time one of the men had graduated, while the other remained on campus and on the crew team. Dunn had dropped the sport to avoid seeing them, and friends dropped her. One urged her to forget about pursuing the case because he didn’t want to testify against one of the accused, who was also a friend.

Both men said the sex was consensual, and neither was ever charged by police or disciplined by the school. It took nine months for the university to tell Dunn it was dropping the case.

“I thought that was it,” Dunn said. But little by little, Dunn, infuriated by her experience, began moving into the spotlight. She joined an on-campus organization dedicated to combating sexual violence. She was quoted in local newspapers talking about sexual violence, and sometimes she discussed her own incident. She caught the attention of Carter, who at the time was with the Clery Center for Security on Campus and running campus safety training programs for college administrators. He advised Dunn to file a Title IX complaint against her university with the US Department of Education’s Office for Civil Rights, often just referred to as the OCR, which she did.

In 2008, the OCR ruled in the university’s favor. By then, Dunn had graduated and was teaching in post-Katrina New Orleans, planning on applying to law schools. But she agreed to take her story national as a favor to Carter, who was working with journalists from the Center for Public Integrity, a nonprofit organization. When the story came out in February 2010, it catapulted Dunn onto the radar of federal officials, including at the White House.

Dunn doesn’t often get emotional, but she does when speaking about statements that President Obama and Vice President Biden made about sexual violence. At a White House event dedicated to combating campus rape in September 2014, Obama credited the survivors who raised hell to get the issue on the nation’s radar. “This is not your fight alone,” Obama said. “You are not alone, and we have your back.” At the same event Biden said, “Our culture still asks the wrong questions. … Never — get this straight — never is it appropriate for a woman to ask, ‘What did I do?’”

“I’m so in awe that the two most powerful men in our entire country were saying everything I wish I heard when I was suffering alone,” Dunn said through tears. One of her father’s early questions about her assault, Dunn said, was, "What were you wearing?"

Dunn recalled that moment one evening in January as she wrapped up work on SurvJustice’s first civil lawsuit, filed against Old Dominion University in Virginia. In the federal suit, a young woman accuses campus police of holding her for hours without access to food, water, medical attention, or bathroom breaks when she reported a brutal rape on Oct. 12, 2014. The lawsuit says campus police declined to press charges despite physical evidence available. Then the school failed to help her as she struggled academically after the assault, according to the lawsuit. By the time Dunn got involved in the case, three months had passed since the assault and the student’s grades had slipped so badly that she’d lost a scholarship.

“It kills us when we think had they reached out a week earlier, a month earlier, they would’ve had a different life experience,” said Dunn.

Since Dunn hit the national stage, she’s often gotten results. Seven years to the day after Dunn was raped, Biden invited Dunn to an event at the University of New Hampshire where the vice president and Education Department officials unveiled a directive that mandated how schools should deal with sexual assault under the gender equity law Title IX. It told schools they couldn’t simply hand cases over to cops, or ignore assaults because they had happened off campus. It said investigations should take no more than 60 days, not the often months-long waits that students — including Dunn — endured after reporting rapes. It was a huge moment for Dunn, and it shook the educational world.

As she listened to Biden, Dunn said, she saw that the pain of having gone public with her own ordeal was worth it. “I received my justice,” she wrote in a blog post that day. “Now it is my turn to help others achieve it.”

Dunn got busy. She spoke alongside Nancy Pelosi as she lobbied in favor of legislation establishing new rights for students in college sexual assault cases. Not only did it pass as part of the Violence Against Women Act’s reauthorization in 2013, but Dunn was picked to be on a committee that helped write how the law would be implemented. The following year, she helped craft a sexual assault policy for the State University of New York system, and then Gov. Andrew Cuomo signed a law mandating that private colleges adopt key pieces of the policy as well.

As Dunn became more active, the 2011 federal directive, which came to be known as the Dear Colleague letter, was gaining steam. The directive led universities nationwide to rewrite their policies on responding to campus sexual assault. As students became aware of the rights they had under Title IX if they were assaulted, they began filing complaints against schools accused of violating them. The number of complaints jumped from 11 in 2010 to 32 in 2013. Last year, it reached 177. In January 2014, Obama launched a White House task force on campus rape and gave the first presidential speech on combating sexual assault.

Campus rape became a proxy for the Obama administration’s larger effort to combat violence against women in general. “The feeling really was if we can get it right here, this will have a ripple effect throughout communities that are affected,” said Rosenthal, who was a White House adviser on violence against women.

Soon enough, there was a culture shift. “No means no” became an outdated mantra, replaced by “only yes means yes” to emphasize that it doesn’t take a woman screaming “no” to show she doesn’t consent. Biden teamed with Lady Gaga at the Oscars in 2016 to talk about sexual violence.

“When I was their age, I didn’t know I had any rights, or I didn’t have any rights — or both,” said Gloria Allred, the feminist attorney, who has gained fame for representing sexual assault victims. “We had no expectation we’d be treated fairly. If anything we had an unconscious expectation of, well, that’s the way the world is, we’re going to get raped and nobody’s going to do much about it. But now there’s a very different expectation among young people, and I’m glad about that.”

However, this cultural change also set the stage for some of the biggest battles SurvJustice and advocates face going forward.

“What I’m so distressed about is that we’ve been working now for a number of years very persistently to change the culture. Now we have a president who believes in attitudes and behaviors, who embodies exactly what we’ve been trying to change,” Rosenthal told BuzzFeed News. “So it’s that, it’s the big picture. What does that mean for our country?”

The surge of activism around campus rape and federal attention to the issue are among the driving forces of the alt-right movement, which started receiving increased attention during Trump’s campaign. For example, alt-right personality Mike Cernovich wrote more than once that he backed Trump in part because he felt elected Republican lawmakers weren’t standing up for men. GOP presidential candidates Ted Cruz and Marco Rubio, Cernovich said, “want men to be expelled from college based on lies.” Breitbart News' Milo Yiannopoulos is currently touring colleges telling students there is an “outbreak of fake rape claims on campus.”

Dunn thinks critics of the movement will be more powerful than ever under the Trump administration. “I don’t think Trump has any agenda on this topic, but I think the people who want to consult with him do,” she said, echoing the conventional wisdom that Trump’s appointees will scale back federal efforts to whip colleges and law enforcement into handling sexual assault better.

Trump’s administration is planning a higher education task force charged with rolling back regulations for colleges to be led by Jerry Falwell Jr., president of Liberty University, an evangelical Christian school in Virginia. Falwell believes sexual assault cases should be left to law enforcement, a Liberty spokesman told BuzzFeed News. That runs contrary to the Obama-era directive, which requires schools to respond to sexual assault reports.

Other critics of the Obama administration’s efforts to fight campus rape include some powerful legal voices who argue it has coerced schools into adopting draconian policies that go beyond what Title IX intended and don’t guarantee the rights of the accused.

“There are men who lie, and women who lie,” famed defense attorney Alan Dershowitz told BuzzFeed News. “The issue is, how do you resolve these difficult factual disputes?”

Dershowitz was one of the Harvard Law professors who asserted that the Education Department’s “relentless pressure” on schools resulted in innocent students being kicked out of school over rape claims.

The Foundation for Individual Rights in Education, a civil liberties group that has long criticized campus sexual assault policies, said the 2011 directive has pushed schools to ditch basic due process protections. “Whatever that letter was supposed to do to make the system better, I don’t see that it has,” said Robert Shibley, FIRE’s executive director.

Many of these critics say they’d rather see sexual assault cases investigated only by law enforcement and taken out of the hands of schools, which might decide to suspend or expel the accused. The federal government has never required any specific type of punishment for a student accused of sexual assault, and most schools opt against expulsion. But critics say colleges are now pressured by the feds to come down hard on accused students. “What I think is a pure fantasy is that expelling someone from campus makes anyone on campus any safer at all,” said Joseph Cohn, a lobbyist for FIRE. “They can still rape someone who went to the same school they were just expelled from.”

Dunn says due process concerns shouldn’t be ignored, and she’s not indifferent to the issues facing some of the accused. When she interned at the public defender’s office in Wisconsin in 2006, working on behalf of people accused of sex crimes, something struck her. As Dunn went through the defendants’ paperwork, she noticed that “almost all of them had been raped as children, or domestically abused by violent parents,” she said. “Everything I read just made me really realize even defendants — a lot of them start as victims themselves and were forsaken by the system.”

SurvJustice’s annual budget is about $160,000, funded largely by a mix of private grants, piecemeal donations, and client fees, enough to cover office rent and three employees. That means Dunn spends a lot of time crisscrossing the country, responding to the more than 550 requests for help SurvJustice has received since its founding. “SurvJustice has always had minimal staffing, and Laura has filled every role at some point,” said Cheri D. Smith, who helped Dunn launch the firm when they both graduated from the University of Maryland’s law school. Referrals to SurvJustice often come from other attorneys, elected officials, activists, journalists, and even college administrators.

Yet Dunn is still learning how to turn connections into donations. In 2015, she became a social entrepreneurship fellow with nonprofit Echoing Green, which provided her fundraising know-how and $80,000 over two years. SurvJustice’s fundraising problem, she said, is that philanthropists would rather donate to rape prevention programs than to a nonprofit that provides legal services to victims.

She had to lay down some rules to deal with the caseload. Dunn won’t take a case with less than a week’s notice, because the one time she did, she had to cram overnight to prep for a hearing, drove to Virginia, got a flat tire, and then the hearing ended at midnight without a break for dinner. “A lot of attorneys I know wouldn’t do a campus hearing but would see the results and do a lawsuit at the end; I get down in the mud,” Dunn says.

Other organizations started by survivors have sprung up alongside SurvJustice, but Dunn’s firm is unique as an organization staffed by attorneys dedicated to providing legal assistance to assault victims at high schools and colleges.

Carly Mee is a fellow college survivor turned attorney who joined SurvJustice last fall, three and a half years after coming forward about being assaulted by a serial rapist at Occidental College in Los Angeles. Like Dunn, she finds the work therapeutic: "There’s a constant influx of survivors who need our assistance, so I don’t have time to stop and feel bad about what happened to me.”

As any SurvJustice client can attest, sexual assault is a unique crime in that it’s common for friends and strangers to disbelieve the victim. By going public about her assault at the University of Wisconsin, Dunn opened herself up to criticism on an even wider scale: Two years ago, the Daily Beast ran an article suggesting Dunn had fudged details and misrepresented and changed her story — even though the writer never spoke with Dunn directly.

The first time Dunn remembers being sexually violated was in high school, and her then-boyfriend didn’t believe her. Dunn was at a party at his house — “a lot of people from our high school were there, a barbecue outside by the pool, things like that” — where she said a guy from school walked by and cupped her ass with one hand and grabbed her breast with the other.

“It’s the first time I’ve ever sworn, the first time I ever hit someone in the face, I threw a drink on him; I felt everything,” Dunn recalled. “I could feel it, as anyone who’s been through any kind of sexual violence can tell you, I could feel it on my body for hours. I couldn’t stop the feeling of having been touched in a way I didn’t want to be touched.” She quickly told her boyfriend at the time, and said his immediate response was, “Are you sure?”

It enraged Dunn, but years later, she would catch herself doing something similar.

One day, after telling her parents about her assault, Dunn was watching the news on TV with her mother. A story aired about a Wisconsin football player convicted of raping his girlfriend — a young woman who’d attended Dunn’s high school, and who Dunn remembered as a girl who would sneak out of her home to party with football players. “I said out loud, ‘Well, that’s what she gets,’” Dunn recalled. “And my mom just looked at me and said, ‘Did you hear what you just said?’ It was like I didn’t even know what I’d said, it was a knee-jerk reaction.”

That brief interaction later helped Dunn realize that even she had victim-blaming mentalities before she dove into the world of advocacy. “Now obviously I’m on the other side,” she said, “but when I get these ignorant people, I think about how I was ignorant. So if I can move forward and learn a little bit, why can’t they?”

Dunn wishes she could be as enthusiastic about Division I football as her current boyfriend is, but she can’t quite figure out how to reconcile the work she does with college athletics. “It’s ruined it for me,” she said.

Even critics of campus rape activism agree that the most egregious injustices in sex abuse cases often happen when a major sports team is involved. Many advocates say part of the reason sexual assault in college gained so much prominence and national outrage was because of the scandal at Penn State, where Jerry Sandusky abused children for years under the protection of the university’s lauded football program. The ongoing sexual assault scandal at Baylor University — where top athletics officials are accused of protecting multiple football players accused of sexual assaults — is only reinforcing that perception of schools prioritizing sports programs above rape. “I know way too much about what’s allowed to be done in the name of athletics, and it just breaks my heart,” said Dunn.

She’s largely moved away from team sports now and avoids an athletic club in DC where some former UW–Madison rowers exercise. She recently became a certified yoga instructor and tries to go for a jog at lunch if she has time to stay healthy amid a hectic lifestyle. She opts for tea instead of coffee, isn’t a big drinker, and tries to eat only organic, nonprocessed food, “which I realize is being privileged but honestly is the difference between me being ill or not,” she said. When she’s not working with SurvJustice’s clients, Dunn teaches a seminar at the University of Maryland’s law school, which boasts about her work and which recruited her to study there based on her Title IX complaint and subsequent activism.

“I love this work, I would love to do it all the time,” Dunn said. “I don’t know if that’s good for my health.” Perhaps influenced by her parents, or because she recently started going to a church in DC, she refers to Scripture from Matthew 26:41: “The spirit is willing, but the body is weak.”

Her parents moved to Florida, and Dunn recently visited them over the holidays — a rare vacation. Dunn jokes that she had to get the president’s attention to mend the relationship with her parents. If you talk to her mother today, Vicky speaks about Dunn like a pastor at the pulpit, calling her daughter “a great advocate in a fallen world.” Ever since Vicky’s daughter went public, older women have revealed to Vicky that they were assaulted at some point in their life but rarely talk about it. “People in an age group where you would never imagine it,” Vicky said.

The country is clearly in a different place. But advocates like Dunn are grappling with what the election of Trump means for the future of our culture and the law. The country just said goodbye to a presidential administration that made it a mission to end rape and is preparing for life under a new leader accused of assaulting more than a dozen women.

On Tuesday, when Betsy DeVos was confirmed as education secretary, Dunn listened to NPR throughout the day as she worked, trying to keep up with the debate. During her confirmation process, DeVos wouldn’t commit to keeping the list of colleges under Title IX investigations public, a policy in effect since 2014. She refused to commit to upholding the 2011 Dear Colleague letter — the very document that made Dunn feel that going public with her own story had been worth it.

A large number of civil rights groups and rape victims advocates campaigned to stop DeVos’s nomination. SurvJustice stayed out of the fight, which Dunn hopes buys her some goodwill with the new education secretary. It’s not that SurvJustice doesn’t have concerns about DeVos, Dunn said hours after the contentious confirmation vote. But in the current environment, she said, blocking DeVos might have cleared the path for an even less desirable nominee.

“Who knows who could be picked," Dunn said. "Even if one nomination doesn’t get through, who knows what the next one looks like."

For now, Dunn said, she is committed to keeping any personal feelings out of the mix as SurvJustice tries to work with DeVos and the Trump administration. How SurvJustice will accomplish that is unclear, she admitted.

“The good and bad news is no one knows how to navigate it,” Dunn said of the new administration. “Our approach is our best guess, and that’s to cling to our values about being survivor-focused. We always want to stand with survivors — nothing else, no one else.” ●