The report reveals that between 1877 and 1950, 3,959 African Americans were lynched — 700 more incidents than had ever been calculated before, the Equality Justice Initiative (EJI) found.

Researchers looked specifically at the "most active lynching states": Alabama, Arkansas, Florida, Georgia, Kentucky, Louisiana, Mississippi, North Carolina, South Carolina, Tennessee, Texas, and Virginia.

The Alabama-based organization poured through local newspaper archives and court records and interviewed scores of local historians, as well as descendants of the victims.

Researchers also focused only on what they called "racial terror lynchings" — which often involved elements of "fear, humiliation, and barbarity" — and did not include hate crimes or other forms of violence for which the perpetrators were charged with a crime.

According to the report, black lynchings in the South occurred when unsubstantiated suspicions arose about black involvement in white society, and when African Americans actively resisted racial subordination.

More than 25% of the lynchings studied occurred because of a "widely distorted fear of interracial sex," particularly between black men and white women. In 1904, a man named General Lee was accused of knocking on a white woman's door in Reevesville, South Carolina. He was lynched by a white mob.

The EJI also recorded lynchings that resulted from "casual social transgressions," which accounted for more than half of the cases. When World War I veteran William Little refused to remove his army uniform in front of a group of white men in Blakely, Georgia, in 1919, he was also attacked and lynched by a mob.

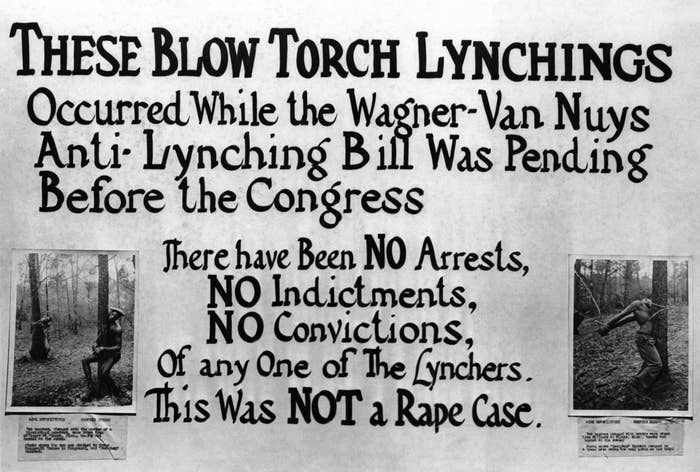

Many of the lynchings were justified by suspicions and lacked hard evidence. Being found guilty of lynching was such a rarity that many of them were carried out in broad daylight, sometimes on the steps of courthouses.

In 1919, Berry Noyse was accused of killing a sheriff in Lexington, Tennessee. According to the EJI report, "an angry mob lynched him in the courthouse square, dragged his body through the town, shot it dozens of times, and burned the body in the middle of the street below hung banners that read, 'This is the way we do our bit.'"

Lynchings were so widely accepted that they became cultural events for white spectators. In one 1904 case in Doddsville, Mississippi, Luther Holbert was suspected of killing a white man. Holbert and the woman assumed to be his wife were captured by a mob and tied to a tree, where white civilians were invited to cut their fingers and ears off.

As the victims were beaten and burned to death, onlookers are said to have been "enjoying deviled eggs, lemonade, and whiskey in a picnic-like atmosphere."

Results of the EJI report suggest that reconciling the past is the only way to effectively address social issues that plague the present.

"Mass incarceration, excessive penal punishment, disproportionate sentencing of racial minorities, and police abuse of people of color reveal problems in American society that were framed in the terror era," it reads.

CORRECTION: The name of the organization that conducted the study on lynching is the Equal Justice Initiative. An earlier version of this story cited the Equality Justice Initiative.