SAN FRANCISCO — On the morning of March 10, nine days after Hillary Clinton had won big on Super Tuesday and all but clinched the Democratic nomination, a series of emails were sent to the most senior members of her campaign.

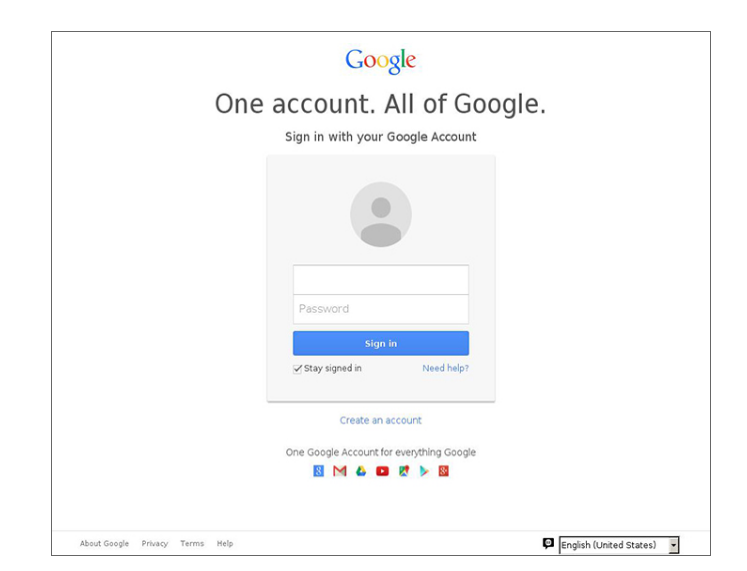

At a glance, they looked like a standard message from Google, asking that users click a link to review recent suspicious activity on their Gmail accounts. Clicking on them would lead to a page that looked nearly identical to Gmail’s password reset page with a prompt to sign in. Unless they were looking closely at the URL in their address bar, there was very little to set off alarm bells.

From the moment those emails were opened, senior members in Clinton’s campaign were falling into a trap set by one of the most aggressive and notorious groups of hackers working on behalf of the Russian state. The same group would shortly target the Democratic National Committee (DNC) and Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee (DCCC). It was an orchestrated attack that — in the midst of one of the most surreal US presidential races in recent memory — sought to influence and sow chaos on Election Day.

The hack first came to light on June 15, when the Washington Post published a story based on a report by the CrowdStrike cybersecurity firm alleging that a group of Russian hackers had breached the email servers of the DNC. Countries have spied on one another’s online communications in the midst of an election season for as long as spies could be taught to use computers — but what happened next, the mass leaking of emails that sought to embarrass and ultimately derail a nominee for president, had no precedent in the United States. Thousands of emails — some embarrassing, others punishing — were available for public perusal while the Republican nominee for president, Donald Trump, congratulated Russia on the hack and invited it to keep going to “find the 30,000 emails that are missing” from Clinton’s private email server. It was an attack that would edge the US and Russia closer to the brink of a cyberwar that has been simmering for the better part of a decade.

The group behind the hacks is known as Fancy Bear, or APT 28, or Tsar Team, or a dozen other names that have been given to them over the years by cybersecurity researchers. Despite being one of the most reported-on groups of hackers active on the internet today, there is very little researchers can say with absolute certainty. No one knows, for instance, how many hackers are working regularly within Fancy Bear, or how they organize their hacking squads. They don’t know if they are based in one city or scattered in various locations across Russia. They don’t even know what they call themselves.

The group is, according to a White House statement last week, receiving their orders from the highest echelons of the Russian government and their actions “are intended to interfere with the US election process.” For the cybersecurity companies and academic researchers who have followed Fancy Bear’s activities online for years, the hacking and subsequent leaking of Clinton’s emails, as well as those of the DNC and DCCC, were the most recent — and most ambitious — in a long series of cyber-espionage and disinformation campaigns. From its earliest-known activities, in the country of Georgia in 2009, to the hacking of the DNC and Clinton in 2016, Fancy Bear has quickly gained a reputation for its high-profile, political targets.

“Fancy Bear is Russia, or at least a branch of the Russian government, taking the gloves off,” said one official in the Department of Defense. “It’s unlike anything else we’ve seen, and so we are struggling with writing a new playbook to respond.” The official would speak only on condition of anonymity, as his office had been barred from discussing with the press the US response to Fancy Bear’s attacks. “If Fancy Bear were a kid in the playground, it would be the kid stealing all the juice out of your lunch box and then drinking it in front of you, daring you to let him get away with it.”

For a long time, they did get away with it. Fancy Bear’s earliest targets in Georgia, Ukraine, Poland, and Syria meant that few in the US were paying attention. But those attacks were where Fancy Bear honed their tactics — going after political targets and then using the embarrassing or strategic information to their advantage. It was in those earliest attacks, researchers say, that Fancy Bear learned to couple their talent for hacking with a disinformation campaign that would one day see them try to disrupt US elections.

“If Fancy Bear were a kid in the playground, it would be the kid stealing all the juice out of your lunch box and then drinking it in front of you, daring you to let him get away with it.”

In late July 2008, three weeks before Russia invaded Georgia in a show of force that altered the world’s perception of the Kremlin, a network of zombie computers was already gearing up for an attack against the Georgian government. Many of the earliest attacks were straightforward — the website of then-President Mikheil Saakashvili was overloaded with traffic, and a number of news agencies found their sites hacked. By Aug. 9, with the war underway, much of Georgia’s internet traffic, which routes through Russia and Turkey, was being blocked or diverted, and the president’s website had been defaced with images comparing him to Adolf Hitler.

It was one of the earliest cases of cyberwarfare coinciding with a real-world physical war, and Fancy Bear, say researchers, was one of the groups behind it.

“When this group first sprung into action, we weren’t necessarily paying attention to the various Russian threat actors, inasmuch as we weren’t distinguishing them from each other,” said one former cybersecurity researcher, who has since left the private sector to work for the Pentagon. He said he could not be quoted on record due to his current job, but that in 2010, when he was still employed with a private company, they had only just started to distinguish Fancy Bear from the rest of the cyber operations being run by the Russian government.

Kurt Baumgartner, a researcher with the Moscow-based Kaspersky cybersecurity company, said the group had the types of financial and technical resources that only nation-states can afford. They would “burn through zero days” said Baumgartner, referring to rare, previously unknown bugs that can be exploited to hack into systems. The group used sophisticated malware, such as Sourface, a program discovered and named by the California-based FireEye cybersecurity company, which creeps onto a computer and downloads malware allowing that computer to be controlled remotely. Other programs attributed to Fancy Bear gave them the ability to wipe or create files, and to erase their footsteps behind them. FireEye researchers wrote that clues left behind, including metadata in the malware, show that the language settings are in Russian, that the malware itself was built during the workday in Moscow and St. Petersburg, and that IP addresses used in attacks could be traced back to Russian sources.

It wasn’t surprising to cybersecurity experts at that time that Russia would be at the forefront of a cyberattack on a nation-state. Along with China, the US, and Israel, Russia was considered to have one of the most sophisticated cyber-offensive capabilities in the world. While China appeared to have its offensive cyber teams largely organized within its military, the US under the NSA, and Israel under Unit 8200, much of Russia’s cyber operations remained obscure.

There are reports from inside Russia that have helped draw a better picture of Russia’s cyber ops. Russian investigative journalists, like Andrei Soldatov, author of The Red Web, have reported on how, following the dismantling of the KGB, Russia’s cyber operations were organized under the FSB, the KGB’s main successor agency. It was a unit operating under the FSB, for instance, that US intelligence officials believe was responsible for years-long cyber-espionage operations into the White House and State Department, discovered in the summer of 2015. At some point, Russia’s main foreign intelligence agency, the GRU, began its own cyber ops. Soldatov said it’s not clear exactly when that happened — though he says it was likely around the time of the war with Georgia — but Fancy Bear is the name given to the most notorious, and apparently prolific, group of hackers working under the GRU.

“Russia’s intelligence agency operates differently. You won’t see officers [in] uniform and hacking into infrastructure. They embed people in various infrastructure places, like ISPs, or power companies,” said Vitali Kremez, a cybercrime intelligence researcher with the Flashpoint cybersecurity firm. “To orchestrate the DNC hack wouldn’t require dozens of people, it would take two or three people, even one person, if he was talented enough. That person would have his orders for that part of the operation, and someone else, somewhere else, might have orders for a different part.”

For years, cybersecurity companies wrote up reports about Fancy Bear, often adding only in the postscript that the group they were talking about was working on behalf of Russia’s GRU. It wasn’t until last week that the US government officially named them as being tied to the highest echelons of Russia’s government.

“What first caught our attention about Fancy Bear was the targets it went after,” the Pentagon researcher said. “This was a group interested in high-stakes targets, and given who they were after — Georgia, Poland, Russian dissidents — it seemed obvious that a Russian government agency would be after those targets.”

In the years following Georgia, the targets that Fancy Bear went after grew in size, sophistication, and scope. One report, by Germany’s intelligence agency BfV, categorized the group as engaging in “hybrid warfare,” meaning a mix of conventional warfare and cyberwarfare. It gave the example of a Dec. 23, 2015, attack on Ukraine’s power grid that left more than 230,000 people without power, and said that Fancy Bear had also tried to lure German state organizations, including the Parliament and Angela Merkel’s CDU party, into installing malware on their systems that would have given the hackers direct access to German government systems. It’s unclear if anyone opened the emails that installed the malware.

The BfV report concluded that these “cyberattacks carried out by Russian secret services are part of multiyear international operations that are aimed at obtaining strategic information.” It was the first time a government had publicly named Fancy Bear as a Russian cyber operation. And there was one attack, on a French TV station, that cybersecurity researchers say was a precursor of things yet to come.

It was just past 10 p.m. on April 8, 2015, when the French television network TV5Monde suddenly began to broadcast ISIS slogans, while its Facebook page started to post warnings: "Soldiers of France, stay away from the Islamic State! You have the chance to save your families, take advantage of it," read one message. "The CyberCaliphate continues its cyberjihad against the enemies of Islamic State.”

The posts prompted headlines around the world declaring that the ISIS hacking division, known as the “cyber caliphate,” had successfully hacked into the French television network and taken over the broadcast.

It took nearly a month for cybersecurity companies investigating the attack to determine that it had, in actuality, been carried out by Fancy Bear. One of the companies, FireEye, told BuzzFeed News that they had traced the attack back to the group by looking at the IP addresses used to attack the station, and comparing them to IP addresses used in previous attacks carried out by Fancy Bear. The ISIS claims of responsibility planted on TV5Monde were just a disinformation campaign launched by the Russians to create public hysteria over the prospect of a terror group launching a cyberattack.

“Russia has a long history of using information operations to sow disinformation and discord, and to confuse the situation in a way that could benefit them,” Jen Weedon, a researcher at FireEye told BuzzFeed News following the attack. “In this case, it’s possible that the ISIS cyber caliphate could be a distraction. This could be a touch run to see if they could pull off a coordinated attack on a media outlet that resulted in stopping broadcasts, and stopping news dissemination.”

For nearly a month, headlines in France and across Europe had speculated about ISIS’ cyber capabilities and motives for the attack on TV5Monde. The stories setting the record straight, and reporting that a Russian group had, in fact, launched the attack, ran in a handful of newspapers for a day or two after the discovery.

At the same time, Fancy Bear was running other experiments, including a campaign to harass British journalist Eliot Higgins, and his citizen journalist website, Bellingcat. Higgins, who had published a number of articles documenting Russia’s alleged involvement in the shooting down of a Malaysian jetliner over Ukraine and the Russian shelling of military positions in eastern Ukraine, suddenly received an onslaught of spear-phishing emails. It wasn’t until this year, when Higgins saw a report by the ThreatConnect cybersecurity company on the DNC hacks that he realized that the emails targeting his site might have been similar to those targeting the DNC. He forwarded the spear-phishing emails to ThreatConnect, which confirmed that he, as well, had been targeted by Fancy Bear.

“I think it is possible that the things we were reporting on caught the eye of the hackers,” said Higgins. “More than anything it's a badge of honor if they are going through so much effort to attack us. We must be getting something right."

Russian media outlets, including Kremlin-owned Sputnik and Russia Today, have run articles suggesting that Bellingcat is linked to the CIA. The Bellingcat website has been defaced with personal photos of a contributor and his girlfriend.

“I think they are worried,” Higgins said. “So they are trying to discredit us.” He said it surprised him that the spear-phishing emails that targeted him and his campaign followed — almost to a formula — those sent to the DNC. The hackers didn’t bother to change the IP address, URL service, or fake Gmail message they used on either his website or the DNC. It was almost, he said, as if they didn’t mind being traced. “They have a government backing them that doesn't care about taking down airliners, and bombing civilians in Syria so maybe they don't care about being caught.”

Both Bellingcat and TV5Monde were, researchers now say, practice runs for Fancy Bear on the use of disinformation campaigns. People would remember a story about a ISIS-led cyberattack on France far more than a story pointing out that it was actually the Russians. Bellingcat’s work on exposing Russian operations would forever be linked, at least in the Russian media, to the accusations that they were CIA operatives. Fancy Bear was honing its skills.

The emails that Higgins, Clinton and the rest of the DNC received were variations of the millions of spear-phishing emails that go out each day. The success of those emails is predicated on the idea that everyone, no matter how savvy or suspicious, will eventually succumb to a spear-phishing attempt given enough time and effort by the attackers.

While Fancy Bear has used sophisticated — and expensive — malware during its operations, its first and most commonly used tactic has been a simple spear-phishing email, or a malicious email engineered to look like it was coming from a trusted source.

“These hacks almost always start with spear-phishing emails, because why would you start with something more complex when something so simple and easy to execute works?” said Anup Ghosh, CEO of the Invincea cybersecurity firm, which has studied the malware found on the DNC systems. “It is the easiest way to get malware onto a machine, just having the person click a link or open an executable file and they have opened the front door for you. Our analysis is on the malware itself, which had remote command and control capabilities. They essentially got the DNC to download malware which let them remotely control their computers.”

Once a spear-phishing email is clicked on, users not only give up their passwords but, in many cases, including in the case of the DNC, download malware onto their computers that gives the attackers instant access to their entire systems.

Cybersecurity experts report that 50% of people will click on a spear-phishing email. In the case of the Democratic Party, Fancy Bear’s success rate was about half of that — but good enough to get them into the accounts of some of the most senior members of the party.

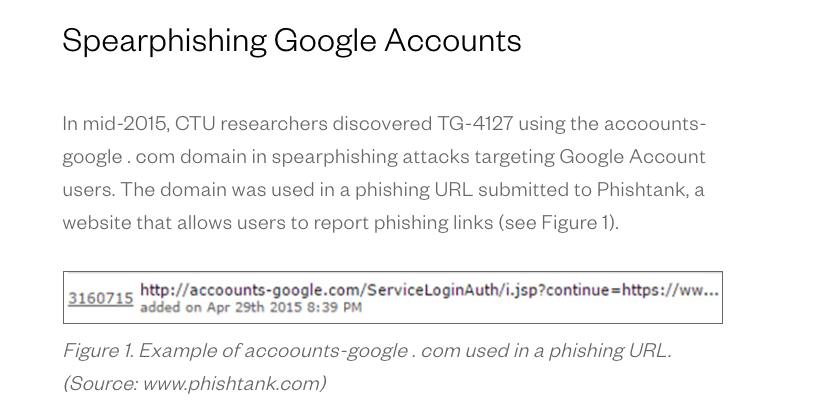

From March 10, 2016, emails appearing to come from Google were sent to 108 members of Democratic presidential nominee Hillary Clinton’s campaign, and another 20 people from the Democratic National Convention (DNC), according to research published by the cybersecurity firm SecureWorks. They found the emails by tracing the malicious URLs set up by Fancy Bear using Bitly, the same service used to target Bellingcat. Fancy Bear had set the URL they sent out to read accoounts-google.com, rather than the official Google URL, accounts.google.com. Dozens of people were fooled.

“We were monitoring bit.ly and saw the accounts being created in real time,” said Phil Burdette, a senior security researcher at SecureWorks, explaining how they stumbled upon the URLs set up by Fancy Bear. Bitly also keeps data on when a link is clicked, which allowed Burdette to determine that of the 108 email addresses targeted at the Clinton campaign, 20 people clicked on the links (at least four people clicked the link more than once). At the DNC, 16 email addresses were targeted, and 4 people clicked on them.

“They did a great job with capturing the look and feel of Google,” said Burdette, who added that unless a person was paying clear attention to the URL or noticed that the site was not HTTPS secure, they would likely not notice the difference.

Once Democratic Party officials entered their information into the fake Gmail page, Fancy Bear had access to not just their email accounts, but to the shared calendars, documents, and spreadsheets on their Google Drive. Among those targeted, said Burdette, were Clinton’s national political director, finance director, director of strategic communications, and press secretary. None of Clinton’s staff responded to repeated requests for comment from BuzzFeed News.

“They did a great job with capturing the look and feel of Google”

In their June 14 report, CrowdStrike found that not only was Fancy Bear in the DNC system, but that another group linked to Russia known as Cozy Bear, or APT 29, had also hacked into the DNC and was lurking in the system, collecting information. The report stated, “Both adversaries engage in extensive political and economic espionage for the benefit of the government of the Russian Federation and are believed to be closely linked to the Russian government’s powerful and highly capable intelligence services.”

The linked names, say the cybersecurity researchers who come up with them according to their own personal whims, are no coincidence. While both bears sought out intelligence targets and infiltrated government agencies across the world, their styles were distinct. Cozy Bear would go after targets en masse, spear-phishing an entire wing at the State Department or White House and then lurking quietly in the system for years. Fancy Bear, meanwhile, would be more specific in its targets, aggressively going after a single person by mining social media for details of their personal lives.

Both bears were in the DNC system, but whereas Cozy Bear might have been there for years, undetected in the background, CrowdStrike has said that it was Fancy Bear, with their more aggressive intelligence-gathering operation, that tipped off security teams that something was amiss. It was also Fancy Bear, cybersecurity researchers believe, who was behind the disinformation campaigns that made public the thousands of emails from the DNC and Clinton.

Making those emails public, say cybersecurity experts and US intelligence officials, is what shifted the hack from another Russian cyber-espionage operation to a game changer in the long-simmering US–Russia cyberwar. Using the well-established WikiLeaks platform, as well as newly invented figureheads, ensured that the leaked emails got maximum exposure. Within 24 hours of the CrowdStrike report, a Twitter account under the name @Guccifer_2 was established and began tweeting about the hack on the DNC. One of the first tweets claimed responsibility for hacking the DNC’s servers, and in subsequent private messages with journalists, including BuzzFeed News, the account claimed that it was run by a lone Romanian hacker, and that he alone had been responsible for hacking into the DNC servers and, later, the Clinton Foundation, as well as senior members of Clinton’s staff. The account offered to send BuzzFeed News emails from the hacks and appeared to make the same offer to several US publications, including Gawker and the Smoking Gun.

Within the week, WikiLeaks had published more than 19,000 DNC emails. Though WikiLeaks would not reveal the source, Guccifer 2.0 gleefully messaged journalists that he had been the source of the leak. Few bought the story — a language analysis on the Guccifer 2.0 account showed it made mistakes typical of Russian speakers, and when asked questions in Romanian by reporters in an online chat, Guccifer 2.0 appeared to not be able to answer. Meanwhile, metadata in the docs, such as Russian-language settings and software versions popular in Russia, led cybersecurity experts to believe that not only were the emails leaked by Russia, but that Guccifer 2.0 was an account created by the Russian state to try and deflect attention.

The same week, a site calling itself DCLeaks suddenly appeared, claiming it was run by “American hacktivists,” and began publishing hacked emails as well.

US intelligence agencies now believe that Guccifer 2.0 and DCLeaks were created by Fancy Bear, or a Russian organization working in conjunction with Fancy Bear, in order to disseminate the hacked emails and launch a disinformation campaign about their origin. WikiLeaks, whose founder Julian Assange has been dogged by his own accusations of close ties to Russia, has refused to state how he got the emails.

“We hope to be publishing every week for the next 10 weeks, we have on schedule, and it’s a very hard schedule, all the US election-related documents to come out before Nov. 8,” Assange said in a recent press conference.

Just weeks before Americans go to the polls, no one knows what material is yet to be published.

In a background briefing earlier this year, one US intelligence officer described cyberwar as “a war with no borders, no innocents, and no rules.” The officer, who has been working on US cyberpolicy for over a decade, said he didn’t think it was a question of if the US and Russia would one day be fighting a full-out cyberwar — it was a question of when.

“They’ve been dancing around each other like two hungry bears for a long time. At some point, one of them is going to take a bite,” said the officer. (His use of the word “bears” appeared to be coincidental.)

The White House’s naming of the Russian government as being behind the hacks attributed to Fancy Bear took the US and Russia into uncharted territory. While no one used the word cyberwar, the statement by the Department of Homeland Security and Director of National Intelligence did not mince words.

“The U.S. Intelligence Community (USIC) is confident that the Russian Government directed the recent compromises of e-mails from US persons and institutions, including from US political organizations. The recent disclosures of alleged hacked e-mails on sites like DCLeaks.com and WikiLeaks and by the Guccifer 2.0 online persona are consistent with the methods and motivations of Russian-directed efforts. These thefts and disclosures are intended to interfere with the US election process,” the statement read. “We believe, based on the scope and sensitivity of these efforts, that only Russia's senior-most officials could have authorized these activities.”

Russian President Vladimir Putin has continued to deny Russia’s involvement in the hacks and said the leaked emails are a “public service.” In a televised address this week, Putin said the hacks were not in Russia’s interest.

“There’s nothing in Russia’s interest here; the hysteria has been created only to distract the American people from the main point of what was revealed by hackers. And the main point is that public opinion was manipulated. But no one talks about this. Is it really important who did this? What is inside this information — that is what important,” Putin said.

The US is still “writing the playbook,” as one Department of Defense official put it, on what happens next, though sanctions, diplomatic action, and offensive cyberattacks are all being considered. Members of Congress have come forward, asking the White House to take aggressive action against Russia. The two countries are, undoubtedly, facing the lowest point in relations in decades.

Fancy Bear and other Russian hacking groups are still active. As countries in Europe — including France, the UK, and Germany — face upcoming elections, what is to stop Fancy Bear from engaging in the same type of hacking and disinformation campaigns?

“They did this to the United States — there is nothing to stop them from doing this to our allies in Europe,” said Jason Healey, former White House director of cyber infrastructure, and a senior research scholar at Columbia University’s School of International and Public Affairs. “We need to be working with our allies and sharing what we know so that this group doesn’t interfere with elections across Europe.”

Baumgartner, the researcher with Kaspersky, said he’s noticed big changes with Fancy Bear. They appear to be spreading out their operations and focus, he said.

“What used to be one focused and narrow group is now several subgroups,” he said. “They might be running independent of each other, or in parallel, but they seem to be spreading out operations.”

Higgins, who runs the Bellingcat website, said that after a lull of almost a year, he suddenly started getting spear-phishing emails again this week that look identical to the ones Fancy Bear hackers sent him last year.

“They’re sending them every day again,” said Higgins. “They are clearly not going to stop.”