On October 6, 1998, Matthew Shepard, a 21-year-old freshman at the University of Wyoming, was strung up to a fence with a length of rope on a remote country road, beaten, kicked, pistol-whipped, robbed, and left to die. After 18 hours bleeding out in the near-freezing cold, Shepard was discovered by a passing cyclist, who initially thought he’d spotted a scarecrow. The first police officer on the scene noticed tear stains streaking through the blood on Shepard’s face.

One year later, in 1999, Aaron McKinney and Russell Henderson — two men Shepard’s age who had left the Fireside Lounge in Laramie, Wyoming, with him the last time he was seen before the attack — were convicted of his murder. Each was given two consecutive life sentences. McKinney, in his confession to the police, said that he and Henderson had targeted Shepard for robbery by pretending to be gay and luring him into their truck, where, McKinney alleged, Shepard placed his hand on McKinney’s knee, which prompted the bludgeoning. Anti-gay attacks were not prosecutable as hate crimes at the time under either Wyoming or federal law. Almost immediately after Shepard was discovered tied to that remote country fence, he galvanized the LGBT movement’s push for expanding hate crimes legislation as news of his attack spread around the world.

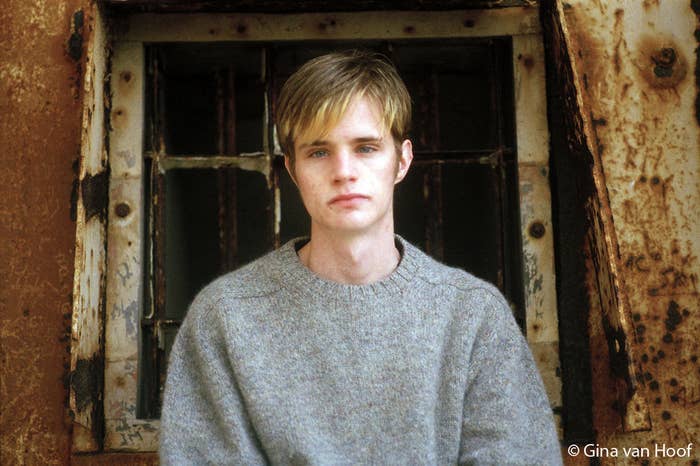

Matthew Shepard was far from the first American victim of anti-LGBT violence. But as a 5-foot-2, fair-haired college kid with braces, Shepard — white, angelic-looking, seemingly innocent — became an easily embraceable symbol for who we stand to lose, should hatred and revulsion toward queerness remain an unchecked fixture of America’s cultural DNA. After McKinney and Henderson’s convictions in 1999, it would take 10 years of thwarted bills before Congress finally passed the Matthew Shepard and James Byrd Jr. Hate Crimes Prevention Act — co-named for James Byrd Jr., a 49-year-old black man who had suffered a brutal lynching-by-dragging in Texas at the hands of white supremacists, the same year Shepard was killed. President Obama signed the bill into law in 2009.

Two weeks ago, 18 years after Shepard’s death, the Justice Department invoked the Hate Crimes Prevention Act to bring criminal charges against a man named Joshua Brandon Vallum for targeting a victim on the basis of gender identity. In US district court, Vallum pleaded guilty to killing 17-year-old Mercedes Williams in 2015 because she was transgender. This was the first time that the Hate Crimes Prevention Act has been used to prosecute an anti-trans attack, though far from the first time a trans person has been killed for who they are. Trans women, particularly trans women of color, are disproportionately affected by violence, including fatal violence. By the end of 2016, the prosecution of hate crimes appeared to be slowly catching up with that reality.

Attorney General Loretta Lynch recently told BuzzFeed News that enforcing hate crimes laws, and conveying their importance to President-elect Trump’s new administration, is one of her top priorities during the transition. It’s hard to imagine Trump’s pick to succeed Lynch, Senator Jeff Sessions, assuming that mantle; his storied anti-LGBT record has included opposition to expanding hate crimes legislation. It’s harder still to imagine the future of hate in America at large, as Trump’s ascension has thrown the country into a nationwide debate about what constitutes hate to begin with.

The Southern Poverty Law Center, a national hate-watch group, recently documented accounts of over a thousand bias-motivated incidents committed against immigrants, people of color, women, and LGBT people in the month following Trump’s presidential victory, including slurs shouted in the street or graffitied onto school walls. But two of the most widely publicized harassment incidents post-election appear to have been hoaxes, casting a shadow of doubt over the majority of legitimate reports. Many Trump supporters assume that every account of a Trump-inspired hate incident has been bogus, insisting that they have been the true victims of hate crimes since the election. (Trump, who recently scolded “those who lost the election” for supposedly threatening his supporters, would appear to agree.)

But suspicions of hate hoaxes long precede Donald Trump. In fact, in the time since Matthew Shepard’s death, there has emerged a growing faction of dissenters who believe that the most famous American victim of what looked to the world like barbaric anti-gay violence — whose life and death have inspired plays, films, and other works of art performed thousands of times across the world — was not killed in a hate crime at all.

Those dissenters found their largest source of validation in 2013, when journalist Stephen Jimenez published The Book of Matt: Hidden Truths About the Murder of Matthew Shepard. Shepard wasn’t murdered for being gay, Jimenez argues, but because of a drug deal gone wrong. Some critics accused Jimenez, who is gay himself, of poor sourcing and flimsy conjecture, but his investigation was convincing enough to inspire doubt in the hearts of many, or affirm the misgivings that others had long held.

Hate in itself, like all messy, unfixed human emotions, is difficult to prove.

Hate crimes are notoriously hard to prosecute. A prosecutor must prove that the defendant committed a criminal act with intent, that he or she acted because of someone’s gender or race or sexual orientation. As the Anti-Defamation League notes, some prosecutors may be wary of the burden of additional evidence required at trial. But most don’t even make it that far: The Bureau of Justice Statistics estimates that only a third of all hate crimes are even reported to begin with. Hate in itself, like all messy, unfixed human emotions, is difficult to prove. And if there is still widespread doubt about the hateful motivations in Matthew Shepard’s murder case, in which the defendants’ own lawyers openly attributed a brutal killing to gay panic, then charting the path of everyday hatefulness on the streets of Trump’s America presents an entirely new challenge.

Social media gives uncorroborated stories — from fudged anecdotes on Facebook to full-scale fake news (a term that is becoming largely meaningless) — the power to spread like wildfire. And that makes hate incidents, among many other stories, difficult to substantiate. We’re living in an age saturated with misinformation. Our curated newsfeeds, even when we’re consuming legitimate news, affirm our confirmation biases. Trump has indicated on many occasions that he’s not a fan of the free press. If the darkest of post-election predictions come to fruition, then the very nature of truth is in question.

Regardless of the future we’re facing, it has already become especially difficult, and especially dangerous, to track the roots of hate in America, precisely because the campaign for hate has won. Immigrants, Muslims, LGBT people, people of color — the Americans most likely to fall victim to hate crimes — have been accused of facilitating Trump’s rise by fracturing the electorate for the sake of “identity politics.” While minority groups are still attempting to discern who among their neighbors actively voted for a candidate who capitalized on bigotry and hatred — or, at the very least, voted in spite of those things — they’re also being shamed for daring to call out the bigotry and hatred they face every day.

When Matthew Shepard’s killers were imprisoned for life in 1999, activists and advocates were hopeful that it would soon get easier to both prevent and prosecute the weaponization of hate. Nearly 20 years later, how much has really changed?

The people of Laramie hoped, at first, that the violent criminals who attacked Matthew Shepard were strangers passing through town. But they were in fact local kids: two of their own. McKinney and Henderson were first charged with attempted murder, in addition to kidnapping and aggravated robbery, but the charge was soon changed to murder in the first degree. After lying in a coma for days, as vigils were held for him around the world, Shepard died in the middle of the night in a Fort Collins, Colorado, hospital on October 12, 1998.

Just as surely as Shepard’s name became shorthand for gay tragedy after his death, the town of Laramie became shorthand for anti-gay hatred. In the days between Shepard’s attack and his death, the NBC Nightly News with Tom Brokaw ran a segment featuring a bar patron saying, “Gays get what they deserve.” Many Laramie townspeople resented that their community was quickly stereotyped by the national press as a bunch of homophobic hicks. The NBC reporter Roger O’Neil was hounded over the following days by residents who were angry that one awful quote was used to depict the entire town’s attitudes, when many were heartbroken and horrified over the attack.

Much of the national media focus on Laramie at the time only reaffirmed preconceived notions about rampant bigotry in conservative flyover states. “Everyone takes note of it because it happened in Wyoming, and then suddenly it’s made to be typical of Wyoming: ‘Oh, it’s a redneck place — we expected it,” one University of Wyoming student told Vanity Fair reporter Melanie Thernstrom at the time.

Even as the nation grieved over Shepard’s death, which inspired tearful words from recently out Ellen DeGeneres and a condemnation of hate crimes from President Bill Clinton, the setting of Wyoming afforded out-of-state mourners a certain emotional distance from the tragedy: This could happen to any gay kid, yes, but the reasoning went that it could especially happen to any gay kid in an insular and conservative patch of the American West.

Most people tend to assume that the kind of hatred that breeds violence, brutality, and murder is something completely foreign to us, as individuals. That terrible thing happened in some other town, born from some other culture, committed by someone with whom you have next to nothing in common. So awful. So sad. But you? Your friends, your family, your community? Never.

Here’s one of the great American falsehoods: Though we live in a country built on the foundations of genocide and slavery, where racism and sexism and homophobia still run rampant, there are apparently very few actual racists or sexists or homophobes here. As David Roberts writes at Vox, “Systemic discrimination becomes a crime with no criminals.”

Millions of people, for example, recently voted to elect Donald Trump, a candidate who ran on a noxious platform of xenophobia. The mythical working-class white voter whose economic anxiety propelled Trump to victory has let many college-educated white liberals distance themselves from the more complicated reality that plenty of college-educated white people voted for him, too. Trump voters were not exclusively pickup truck–driving factory workers in flyover states — they were our neighbors, our colleagues. Members of our families. That’s a reality white Americans must actively reckon with now, even though it’d be far easier to assume that stoking paranoia and hatred of the Other is something that only happens in a different kind of America.

Paranoia and hatred was not, and never has been, confined only to places like Laramie, Wyoming.

Paranoia and hatred was not, and never has been, confined only to places like Laramie, Wyoming. But in 1998, that community still had to deal with what had happened there.

“We’re ‘live and let live.’” That line was repeated over and over to the creators of The Laramie Project, a widely performed play based on hundreds of interviews with inhabitants of the town. Members of the Tectonic theater company were told that in Laramie, everybody minds their own business. One gay man summarizes the ethos: “If I don’t tell you I’m a fag, you won’t beat the crap out of me.”

Aaron McKinney claimed that Shepard broke that unspoken rule, which inspired his eruption of violence: Shepard made at a pass at him. But Shepard’s friends didn’t believe he would ever do such a thing — take that kind of risk.

In 1999, when the Hate Crimes Prevention Act was reintroduced in the House and the Senate following the widespread outcry over Shepard’s death, his mother, Judy Shepard, spoke before a US Senate panel. “My son Matthew was the victim of a brutal hate crime,” she said, “and I believe this legislation is necessary to make sure no family again has to suffer like mine.”

Various attempts at expanding hate crimes legislation were introduced over the years, only to be stripped away in conference committee or abandoned after threats of presidential veto by George W. Bush. Finally, in October 2009, President Obama signed the Matthew Shepard and James Byrd Jr. Hate Crimes Prevention Act, a provision of the National Defense Authorization Act, into law. Among other measures, the act expanded existing federal hate crimes law to include more bias motivations (including sexual orientation and gender identity). Eleven years had passed since the deaths of both Matthew Shepard and James Byrd Jr.

Although a hate crimes bill was introduced in the Wyoming state legislature shortly after Shepard’s death, it ended up failing in the House. Forty-five states and Washington, DC, currently have statutes that criminalize bias-motivated violence, the majority of which cover sexual orientation and a handful of which include gender identity. One of five states that are still without any sort of hate crimes law is Wyoming.

"I believe Matt's murder is the defining moment in the history of Laramie and Wyoming," Reverend Stephen Johnson told the Advocate reporter Phil Curtis a year after Shepard’s death. "A century ago Wyoming prided itself as the Equality State, the first in women's suffrage; a century later, and it has to rethink what that equality means and extend it to all its citizens."

But when the Tectonic theater company returned to Laramie to work on their epilogue, Laramie Ten Years Later, the mood of reflection and healing there had changed. Stephen Belber, who worked on both iterations of The Laramie Project, told the Denver Post that “so much of the town is rewriting the crime as not a hate crime.”

Suspicions had long ago started brewing that Shepard hadn’t been the victim of gay hate after all, but rather of a different Western cliche: a drug-related robbery meeting a violent end. In 2004, 20/20 aired a report claiming as much with interviews with McKinney, Henderson, McKinney’s girlfriend Kristen Price, and the prosecutor on the case. During the special, McKinney said he’d been motivated only by robbery, not hatred of gay people. Later, in 2013, journalist Stephen Jimenez (whose early reporting informed the 20/20 segment) gave renewed credence to those claims when he published The Book of Matt.

After over a decade’s worth of reporting, for which Jimenez spoke with a hundred-plus Laramie residents and people involved in the case, he concluded that Shepard was a meth user and occasional dealer who not only knew his killers, but had previously had sex with McKinney (which McKinney has always vehemently denied).

At ThinkProgress, Alyssa Rosenberg slammed The Book of Matt for what she deemed its dubious reporting methods and misleading quote formatting, as well as failing to establish the credibility or motivations of its sources. The lead sheriff’s investigator on the case said the book was filled with “factual errors and lies.” But other officials were more circumspect. The prosecutor on the case maintained that there was enough evidence to indicate that drugs were at least a factor in the killing.

As Matthew Shepard evolved from the pure and blameless “patron saint of hate-crime legislation” (as JoAnn Wypijewski described him in Harper’s in 1999) to a shadowy figure who had potentially fallen victim to a far more pedestrian tragedy, Wyoming was slowly but surely exonerating itself. Or, at least, Laramie’s macho-cowboy culture was now culpable for a less abominable crime.

While looking into the alternate theories surrounding Shepard’s death, I asked my girlfriend, who grew up gay in northern Wyoming in the ’90s, whether people there considered him a gay martyr.

“You can’t have a gay martyr without any visible gayness,” she said. The burst of visibility that Shepard’s death brought to the existence of gay people in Wyoming soon flared out. As far as she’d heard, the real reason he got killed had to do with meth — but that was more silently known in her small community, rather than debated or discussed. For the most part, she said, no one ever talked about Matthew Shepard.

In a 2014 piece for The Guardian, reporter Julie Bindel spoke with a few involved parties, including a police officer named Flint Waters, who had detained Henderson and found McKinney’s truck with the murder weapon. “I believe to this day that McKinney and Henderson were trying to find Matthew’s house so they could steal his drugs,” he said. He added that “some of the officers I worked with had caught [McKinney] in a sexual act with another man, so it didn’t fit — none of that made any sense.”

Bindel concludes that “the mystery remains — not so much why Matthew died, but why the gay community, after almost five decades of campaigning for equal rights, relies so fundamentally on the image of the perfect martyr to represent the cause.”

The question of why Shepard died has always been framed in binary terms. LGBT advocates, including GLAAD and the charity foundation established in Shepard’s name, have rejected Jimenez’s reporting on the case wholesale. Jimenez and others who float drug violence theories, including members of the right-wing press convinced of a massive gay conspiracy, chalk up the pushback against those theories to political correctness and an unwillingness to reckon with uncomfortable truths. Within hours of Shepard being rushed to the hospital, his friends had contacted media companies claiming he’d been attacked for his sexuality; Shepard’s story as a gay martyr, some argue, was written long before all the facts could be gathered. Now, those in Jimenez’s camp figure that people who want to believe Shepard died because of his sexual orientation have a misguided need to immortalize him as infallible.

An apparently innocent martyr will always be an easier sell to a skeptical country than someone who violates society’s rules, whether or not they do so out of necessity. Drug users, sex workers, and petty criminals, even when they’re brutally murdered, aren’t afforded much national sympathy. Presenting Shepard as a squeaky-clean saint, however, doesn’t do his memory any favors; he was a real live person, not just our gay poster child. There’s validity to Jimenez’s criticism of the whitewashed, safe, and politically sterile campaign for LGBT rights.

But, crucially, Jimenez’s critics aren’t merely concerned about preserving a perfect victim. The people closest to Shepard, including his mother, have never maintained that Shepard was a saint. Even if Jimenez is right, and Shepard had once slept with his attacker, or bought and sold meth, those things still wouldn’t matter if he was truly targeted, in one way or another, for being gay. Ultimately, what's concerning is the suggestion that Shepard’s alleged drug use, his flaws and poor judgments, could somehow render his sexuality (and his assailants’ apparent and ongoing hatred of that sexuality) irrelevant. To imply that a man who may or may not have previously slept with other men cannot harbor hatred for gay people, for instance, reveals a profound misunderstanding of the power and pervasiveness of internalized homophobia.

Almost 20 years later, it’s impossible to know exactly what happened to Shepard, and why — but the evidence, however murky, is now stronger than ever that his story is more complicated than it appeared in its earliest iteration. Most stories are. That doesn’t mean, however, that anti-gay sentiment couldn’t have played any part in his death. When Greg Pierotti of the Tectonic theater company interviewed Aaron McKinney for Laramie Ten Years Later, McKinney expressed that he had no remorse. “Matt Shepard needed killing,” he said. “The night I did it, I did have hatred for homosexuals.”

McKinney acknowledged that he’d set out with the goal of robbery, but he said he targeted Shepard for a reason. “He was obviously gay. That played a part. His weakness. His frailty.”

The question becomes how much hate is enough hate to count.

The question becomes how much hate is enough hate to count. How pure that hate must be, how untainted by other motivations of aggression, or pleasure, or negligence, or greed — whether or not human behavior can be so neatly demarcated.

The most Shepard truthers can prove in the end is that there are rarely, if ever, any “good” victims of hate crimes, especially the further a victim gets from the straight white male American ideal. Shepard, a fair-haired, blue-eyed gay boy, garnered enough national sympathy to spur the signing of a federal law in his name before his reputation in certain corners began to sour. But other sorts of victims without the protective sheen of whiteness are afforded much less after death. Take some of the many black men and boys felled by police violence in recent years: 18-year-old Michael Brown was “no angel”; Trayvon Martin, also a child when he died, was a “thug.”

Or take the dozens of trans women of color who have been killed — oftentimes by sexual partners — over the past decade, and long before that, when their genders were rarely recorded correctly in death. It’s all too common to hear arguments that these women “deserved” what they got because they “tricked” men: The US Marine who killed trans Filipina Jennifer Laude did so because he felt “disgusted and repulsed”; the District Attorney representing the case of Gwen Araujo, a trans teenager brutally killed by four men in California, misgendered Gwen and accused her of “making some decisions in [her] relation with these defendants that were impossible to defend.” (In 2006, the Gwen Araujo Justice for Victims Act limited the use of the gay and trans panic defense by criminal defendants in California.) Whether or not hatred, or its not-too-distant cousins — institutionalized racism; state-sanctioned violence; culturally codified bigotry — came into play during any given killing, the people killed so often receive more scrutiny than those who killed them.

So, too, was the case with Matthew Shepard. “Obviously, the killing was about homosexuality,” writes Melanie Thernstrom in her story on Shepard for Vanity Fair, “perhaps sharpened by class envy and by drugs as well. But could Aaron and Russell have murdered someone else for some other reason?” She mentions that after leaving Shepard to die, when McKinney and Henderson were en route to burglarize Shepard’s house, they attacked two Hispanic teenagers named Jeremy Herrera and Emiliano Morales, shouting slurs; McKinney ended up smashing Morales' skull. He needed 21 staples in his head. “At the deepest level, murder is simply about murder,” Thernstrom writes, “about having the capacity, rage, and will to do it, and about finding a victim who can be dehumanized by the shallowest of spells.”

McKinney and Henderson have already been retried again and again in the court of public opinion, ever since they were convicted of murder, without the specification of hate, in 1999. If the same killing had occurred today, Wyoming still wouldn’t be able to try either man for a hate crime. Federal hate crime prosecutions, meanwhile, are relatively rare, but they do happen — as in the case of Dylann Roof, who was recently convicted of 33 counts of federal hate crimes for massacring nine black churchgoers in Charleston, South Carolina, last year.

Hate is alive today just as it was, in some form or another, on that cold night in Wyoming in 1998. And no matter whether or not McKinney and Henderson would meet the standards for a hate crime if they were tried in a court of law today, Matthew Shepard — a gay college student who had his whole life ahead of him — is still dead.

In a post-marriage-equality America, some LGBT people (particularly those who are white, cisgender, nondisabled, and middle-class) began to slip into a kind of hesitant complacency. LGBT people were finally handed a long-fought-for victory, which would leave nearly every other problem on the table unsolved, but would at least free up space for focusing energies elsewhere. Marriage gave everyone a moment to pause, and celebrate, and feel hopeful, before getting back to work.

In the same way that more privileged queer people on the coasts were able to geographically distance themselves from the horrors of Shepard’s death in 1998, the Supreme Court’s landmark marriage equality decision in 2015 let them do so temporally: That kind of violent hatred, many figured, is mostly a thing of the past. White gay men like Matthew Shepard, while still the occasional targets of hate-based incidents, have been faring far better than other LGBT people on the margins, particularly trans women of color.

2015 was the year we had the audacity to think that perhaps things really could get better.

2015 was the year we had the audacity to think that perhaps things really could get better — and not just for privileged LGBT people who were already enjoying the benefits of queer assimilation. 2016 was the year we learned that those had been desperately foolish hopes.

During LGBT Pride Month this past June, a shooter opened fire at a gay nightclub in Orlando, killing 49 people, most of whom were queer and Latinx. The massacre at Pulse was a hateful act of horrific proportions, committed against queer people who were enjoying a night out in a place they felt was safe. Here was a wakeup call to complacent queers: All of us, but especially those who don’t benefit from white supremacy or gender conformity, were not safe from hatred. Maybe we never really had been.

Orlando is a diverse, tolerant city, and the reality that a place like Pulse could be the site of such a heinous crime disturbed and frightened LGBT people who had fled from less loving hometowns to more liberal coastal cities. That shift has been a longtime demographic trend in the US, but it’s no longer the only trend. Earlier this year, when Consumer Affairs analyzed US Census data and Gallup polling to track the moving trends of LGBT Americans, they found that the number of LGBT people who have relocated to red states grew steadily between 1990 and 2014. Historically gay-friendly cities on the coast, like New York and San Francisco, still have relatively high LGBT populations. But as historic gayborhoods started losing their queer spaces to gentrification, many queer people were simultaneously priced out of those areas and then out of those cities altogether.

LGBT people have begun favoring smaller, cheaper cities in states like Utah, Indiana, and Georgia. Though many red states, including Wyoming, still lack state-level LGBT anti-discrimination laws, LGBT people are currently protected by various federal orders instituted by the Obama administration. “With national laws starting to reflect the growing societal acceptance and awareness, state laws are starting to matter less when it comes to where LGBTQ individuals choose to live,” ConsumerAffairs content manager Ryan Daly told the Daily Beast in March.

A few months later, Donald Trump was elected president.

Though he took the time during his presidential campaign to deride Muslims, immigrants, disabled people, women, and people of color, Donald Trump didn’t really target LGBT people in his verbal attacks. (He’ll tell you — just “ask the gays.”) Trump has flip-flopped on many queer and trans issues; besides using LGBT people to invoke the specter of radical Islam, he doesn’t seem personally invested in either forwarding or unraveling pro-LGBT policies. While no one can accurately predict what a Trump presidency will mean for LGBT people, many of Trump's picks for his cabinet and other positions so far have a history of opposing LGBT rights. One of them is North Carolina Representative Virginia Foxx, who has been tapped to head the House Education Committee. During a debate over the expansion of hate crimes legislation on the House floor in 2009, she called the designation of Matthew Shepard’s murder as a hate crime “a hoax.” Trump’s attorney general nominee, Senator Jeff Sessions, whose nomination has been opposed by many civil rights groups — including the NAACP this week — has an anti-LGBT record to match that of Indiana governor and Vice President-elect Mike Pence.

Now that federal protections for LGBT Americans are potentially in jeopardy — particularly those for trans people — LGBT people around the country are weighing their options. My girlfriend is an outdoors fiend who would move from New York back to Wyoming in a heartbeat if the cultural landscape was different there. She comes alive when she goes home; she was built to run on mountain trails, to spend days alone in a tent in the middle of nowhere. When she tells New York friends about joggers in Wyoming who are sometimes presumed murdered because their bodies are so badly mutilated (most of the time, they’re just the victims of mountain lions) she does so with bubbly nonchalance. But she’s more frightened of living her life among people who, at best, don’t fully understand her — and at worst, would wish her harm — than what lies waiting in the Western wilderness. The small town where she grew up is filled with wonderful, big-hearted, and tolerant people who’ve loved her since she was a kid; it’s the strangers, she says, that you have to worry about. She doesn’t have high hopes that her state, more than 68% of whose tiny population voted for Trump, will be welcoming her home with open arms anytime soon.

Of course, even a liberal haven like New York City is not an oasis of safety. By the end of 2016, hate crimes here were up by 31%. (Though me and my gender-nonconforming girlfriend, both of us white, are far safer here than New York’s many immigrants and Muslims, who have been the targets of most of the recent attacks). Also at the end of 2016, the FBI released its statistics on hate crimes from the year before, a collection that marks the 25th anniversary of the bureau’s work compiling this data. Though anti-Muslim and anti-Semitic incidents saw some of the biggest spikes, of over 7,000 reported bias-motivated crimes in the US in 2015 — a tiny fraction of the actual likely number of incidents — 17.7% were a result of sexual orientation bias. It’s tough to envision the Trump administration, and a Department of Justice under Jeff Sessions, treating the prevention and prosecution of bias-motivated crimes as a priority. After all, hate crime legislation is the perfect criminal-justice encapsulation of “identity politics,” which is so often considered a silly liberal distraction from the problems of “all” Americans. (All Americans, that is, if you only count the white, straight, cisgender ones.)

Hate is a hard thing to prove. Many are unwilling to recognize it in people with whom we share a country; far more are unwilling to recognize it in themselves. Hate can be brushed off, minimized: Some faceless bigots slinging slurs online might not seem like so much of an individual threat, but they start to look a little different in light of the news that Dylann Roof was motivated to slaughter nine black churchgoers in Charleston by “things he saw on the internet.”

In Trump’s America, the victims of hatred will not be martyrs, but complicated human beings, just like everybody else.

Hate can also be discounted, excused: If one thinks that Matthew Shepard had bought or sold meth, then perhaps one could regard his brutal killing with a sense of inevitability rather than only anger and horror — the power of hate blunted by its victim’s failings. But no victim can be, or should be, a secular saint. In Trump’s America, the victims of hatred will not be martyrs, but complicated human beings, just like everybody else. And many will be targeted by acts of hatred that aren’t nearly as sensational as murder, but with burdens of proof just as high — or, potentially, higher.

The LGBT movement, like every other battle for civil rights, is not a simple, straightforward march toward liberation. In the coming years, as being labeled a racist or bigot is falsely equated with acting out of racism or bigotry, as evidence of hate and its terrible outcomes is clouded by self-interested, suspicion, and denial — it’s worth remembering that in 2016, love did not trump hate. Far from it. Hate in America is alive and well. And without at least attempting to recognize it, we have no hope of defeating it.

This is part of a series of essays on the year 1999; you can check out the other stories here.