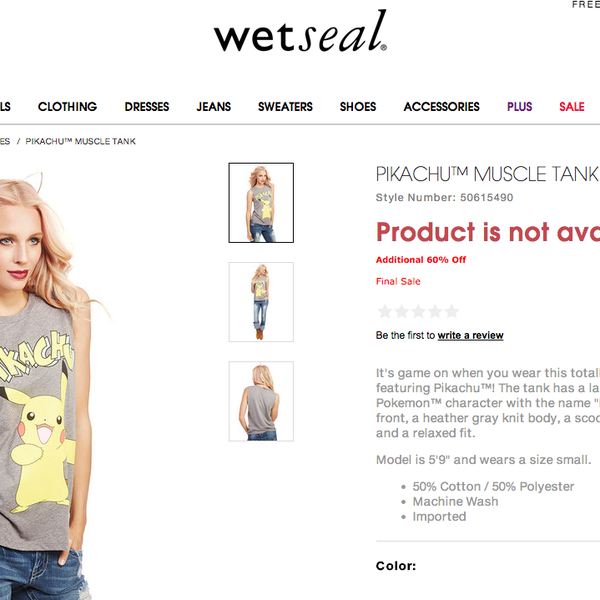

On Wet Seal's website, there's a model in a Pikachu "muscle tank," gazing to her left as her blonde hair flies across her face, one hand in the pocket of her bizarrely folded jeans. Are they bell bottoms? What's with the cat-ear tiara on her head? Pikachu beams.

The graphic T-shirts featuring Pikachu, Frozen's Elsa, Barbie, and The Lion King, at a retailer targeting sophisticated 20-year-olds, perfectly illustrate Wet Seal's decade-long struggle to figure out who its core customer is. It's a struggle that could soon end in the company's bankruptcy.

Wet Seal, which was among the hottest teen retailers in the '90s and early 2000s, is the latest chain running out of reasons to exist. It announced in a quarterly filing this month that based on recent losses, "there is substantial doubt about our ability to continue as a going concern." Its stock closed Friday at 5 cents a share, after announcing late Thursday that its executive overseeing stores and operations will resign on Jan. 2. Its lender, Bank of America, has tightened the reins, keeping a close eye on its cash levels.

Wet Seal, which brought back its old CEO this past September in a last-ditch turnaround attempt, has been bleeding cash and losing customers in recent years as executives keep changing their mind about who they're selling to. Management has struggled to prove they understand the changing face of the American teen market, a fact highlighted by a troubling lawsuit, settled last year, that alleged the company sought to hire more white retail staff to achieve the "diversity" needed to reach its target market.

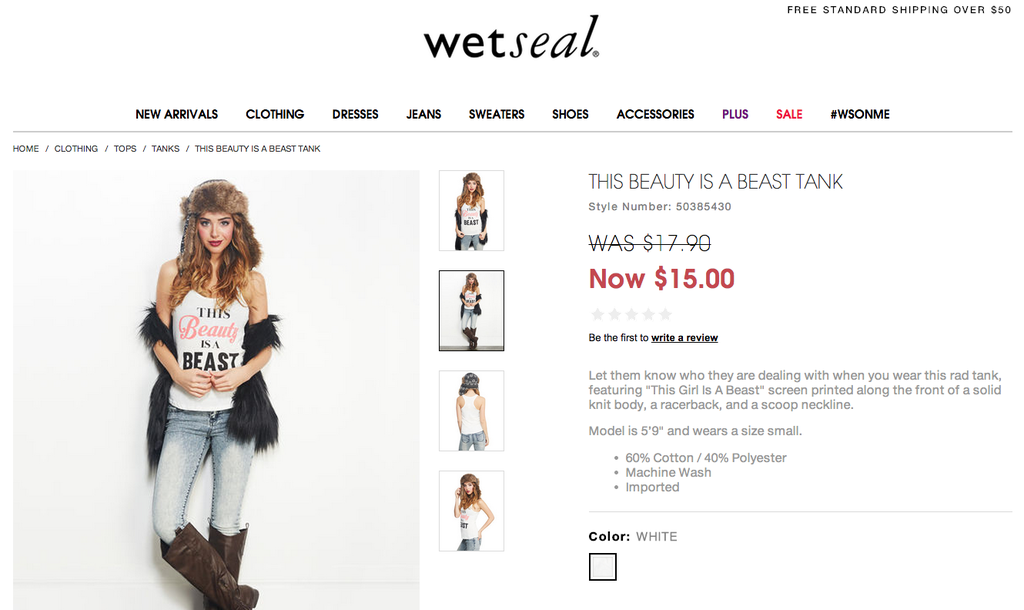

The retailer's newly installed executive team says it finally has it right: Earlier this month, Wet Seal's CEO said it wants to become "sexy" and "edgy" again, market to 18- to 24-year-olds rather than 13- to 23-year olds, bring back the old Contempo Casuals label, and get out of "juvenile" graphic tees.

But those changes won't really hit until this spring, and Wet Seal is in extremely tight financial straits during a sluggish holiday shopping season. Adding to that, the liquidations of rivals DEB and Delia's are intensifying mall competition this month, as those retailers clear out dirt-cheap inventory and lure customers in with giant "Going out of Business" signs.

"It sounds like the current management team, which was the old management team, really believes in this sexy, more sophisticated look and believes the customer target got too young and too basic," Liz Dunn, founder and CEO of retail consulting firm Talmage Advisors, tells BuzzFeed News. "They want to interject more fashion as quickly as they can, and raise the level of sophistication. I just don't know if they have enough time, and with the stock at 5 cents the market's kind of goading."

Wet Seal's spokesperson and CFO, both contacts on recent press releases, are no longer with the company. A message left at interim CFO Thomas Hillebrandt's office was not immediately returned. The company's receptionist wouldn't provide an email address to send questions to.

Wet Seal, founded as "Lorne's" in Newport Beach, California, in 1962, plays in the league of teen retailers like Charlotte Russe and Forever 21. It has typically, for the past 15 years, brought in somewhere around half a billion in annual sales from the web and many malls, making it smaller than chains like Abercrombie or Aeropostale. As of Nov. 1, the company counted 528 Wet Seal locations. It also used to own Arden B, a chain targeted at 24- to 34-year-old women, but has been winding down that brand this year. Most were turned into Wet Seal Plus stores while others converted to regular Wet Seals; one retained the Arden B name.

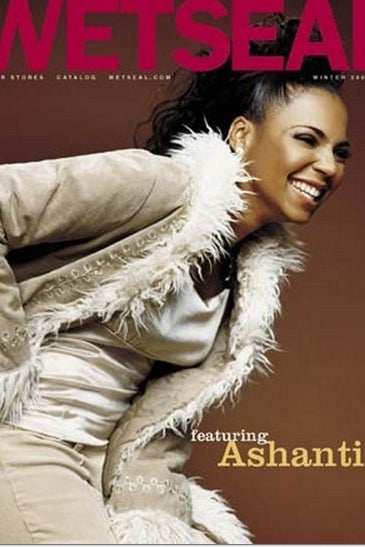

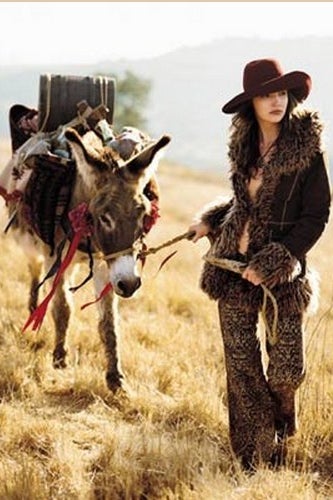

During Wet Seal's heyday in the late '90s and early 2000s, it was cool and moderately priced — $22 halter tops, $38 dresses, $40 jeans. It had a strategy of running sweepstakes or partnering with hot pop music acts to reach its target demographic. Today's twentysomethings might recall its work with Mandy Moore, who was 15 at the time. Wet Seal wanted the kind of girl who listened to her music, and that of NSYNC and the Backstreet Boys. It featured Ashanti on the cover of a 2002 catalog. It regularly held contests, giving away concert tickets for No Doubt, the Goo Goo Dolls, BBMak. It was able to use a picture of a model wearing a fur-lined coat and Carmen Sandiego hat while leading a burro through a field to successfully sell clothing to teenagers.

"When I was in my teens, Wet Seal was Forever 21 — it was where you went to get all your cool outfits," says Jaclyn Johnson, who runs the blog Some Notes on Napkins and founded marketing and event agency (No Subject.) "It was sort of first to market in understanding fast-fashion and getting in touch with that teen market and really nailing that," she says.

But reading through Wet Seal's conference call transcripts from the past decade, it's clear that its revolving door of leadership completely lost control of that cool. In 2004, an executive explained to investors that Wet Seal previously made the mistake of targeting a "very young" 14-year-old customer, then jumping to a 22-year-old customer, but the company planned to get back to 17- to 19-year-olds. In 2010, executives discussed new efforts to focus on the "younger teen." In 2013, former CEO John Goodman said the Wet Seal customer was a 16-year-old girl obsessed with fashion. The annual report last year said it was for 13- to 23-year-olds. Now, Wet Seal says it's again for 18- to 24-year-old women.

In all, that's pretty confusing for anyone who knows the difference between what a middle schooler wants to wear versus a recent college graduate.

More recently, Johnson points out that Wet Seal's merchandise is confusingly all over the place — it carries sassy Nasty Gal-type T-shirts, "festival-going" wear you might find at Free People, and general fast-fashion basics you'd see at Forever 21, in what seems like a bid to see what sticks.

Adding to that, Wet Seal's past behavior shows the company may have lost additional sales by rejecting some of the young women who did want to wear the chain's clothes.

Just last year, the company agreed to pay $7.5 million to settle a deeply embarrassing lawsuit that showed it transferred black employees to lower-volume stores, fired them, and hid them on store checks to maintain a certain kind of brand image. Those orders, as per the complaint, came from top executives at the company. The Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, which got involved in the case, said in a filing that "an analysis of documental and testimonial evidence reveal that corporate managers have openly stated they wanted employees who had 'the Armani look, were white, had blue-eyes, thin, and blond in order to be profitable.'"

The push for an "Armani" look is somewhat ironic given Wet Seal is perhaps best known among teens for its five basics for $20 deal. One of the black women bringing the lawsuit alleged that her district manager was crying when she fired her because the dismissal was so unmerited.

Wet Seal allegedly told store managers that they needed "to hire more diversity" — that is, more white employees — to obtain a higher-income shopper who might be spending money at the likes of Abercrombie. Most damning was an email from a senior executive included with the complaint that showed she wrote, after store visits in Maryland and Philadelphia: "Global Issues: "Stores Teams - need diversity African Americans dominate - huge issue."

Even now, the stores don't feature a lot of models who are "ethnically diverse" or the "sexy, more sophisticated and older look that management's targeting going forward," Liz Dunn of Talmage Advisors explained.

Wet Seal's woes have been complicated by the involvement of activist hedge fund Clinton Group, which started pressuring the company to sell itself in 2012, believing it could fetch a price of $5 to $8 a share. The stock, now trading at just pennies, hasn't been above $5.15 in the last five years — down substantially from the glory days of $25 a share in 2002. Ed Thomas, who returned to the company as CEO a few months ago, is the company's third in four years. Much of the board has been replaced by the hedge fund, and almost the entire management team turned over between July 2012 and April 2013.

Since the return of Thomas as CEO, the company's stock has plunged more than 80%. In a Nov. 19 statement, the Clinton Group said the extent of the drop was something it "did not anticipate was in the realm of possibility when we suggested his name to the Board in August."

But the hedge fund is backing the CEO, and says the board should be able to find a buyer or backer for the company. "We are confident that there are a number of strategic and financial investors that would back Mr. Thomas in a turnaround at Wet Seal," it said in the November statement. "The Board should be running a tight process, not disruptive to management, to seek a transaction with these investors as a potential alternative for the company."

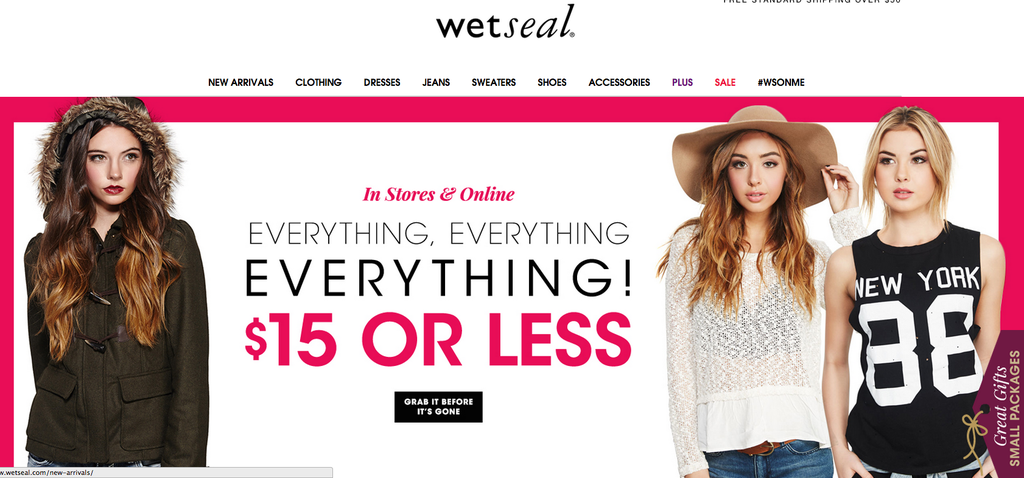

Any buyer will need to factor in the extent of the turnaround needed. Sales have plummeted for 11 of the past 12 quarters, margins have seriously deteriorated — right now, everything on the website is going for $15 or less — and it's unclear when Wet Seal will return to profitability.

On the other hand, the company has shown impressive survival skills thus far. Back in 2004 the New York Times reported Wet Seal could be going bankrupt "any day now." The problem, way back then? Apparently, it had lost its cool among teenagers.